- Ecuador’s Jama-Coaque Reserve, home to a vibrant cloud forest ecosystem, is part of what may be world’s most endangered tropical forest, of which only 2.23% remains.

- The Third Millennium Alliance (TMA) manages the Jama-Coaque Reserve, protecting one of the few remaining forest areas by monitoring and rebuilding the surrounding forest and with sustainable cacao farming that supports the local economy.

- Through their regenerative cacao program, TMA pays local farmers to transition from unsustainable practices to shade-grown cacao cultivation while providing access to premium markets to sell their cacao.

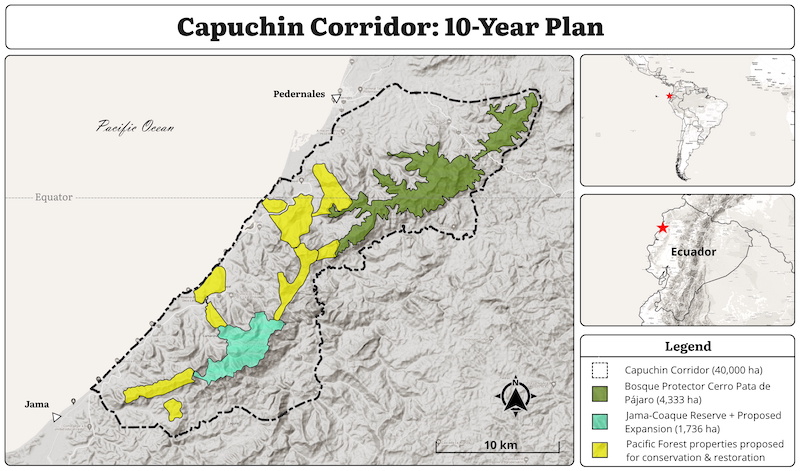

- TMA is also working to build “the Capuchin Corridor,” a 43-kilometer (27-mile) wilderness corridor connecting some of the remaining forest fragments through land purchases, agroforestry and reforestation.

In Ecuador’s Jama-Coaque Reserve (JCR), nearly every surface is encased with life: moss, ferns, epiphytes and orchids — a color wheel of green in three dimensions. Amid the green, chestnut-headed oropendola nests hang like woven teardrops from towering trees, troops of howler monkeys shout their boundaries and hummingbirds dive-bomb from branch to blossom.

The JCR protects around 2% of what may be the world’s most endangered tropical forest, Ecuador’s Pacific Forest, and is managed by the US- and Ecuadorian-based nonprofit Third Millennium Alliance (TMA).

Jerry Toth, TMA’s co-founder and program director, describes the first time he visited the forest that would become the reserve. “We found … a wealth of exotic palm trees with spiny trunks … stands of giant bamboo and countless little streams tumbling down steep slopes, alternating between waterfalls and itty-bitty swimming holes naturally stocked with freshwater prawns.”

Yet surrounding this patch of paradise in all directions was “a sea of deforestation.”

Inspired and alarmed, Toth and two others formed TMA and raised $16,000, mostly from family and friends, to buy their first 100 acres and create the reserve in 2007. Their mission: “Keep this forest alive.”

The JCR now protects 1,024 hectares (2,530 acres), and with it, dozens of endangered species. According to Ryan Lynch, TMA’s director and wildlife biologist, they have seen or photographed many of these, including the white-fronted capuchin monkey (Cebus aequatorialis), Ecuadorian blue glass frog (Cochranella mache), gray-backed hawk (Leucopternis occidentalis) and the Hotel Zaracay salamander (Bolitoglossa chica).

Ecuador’s Pacific Forest is one of the most biodiverse places in the world. But, according to a 2021 survey by TMA, only 51,000 hectares (126,000 acres) of the original forest is left, scattered in small fragments across the region. That is a mere 2.23%.

As in much of northwest Ecuador, forests here have been cleared primarily by slash-and-burn methods for cattle ranching, palm oil, teak, corn, cacao and other crops. TMA realized that to stop further deforestation and regrow forests, they needed to create different ways for people to make money.

“Because food production is the main threat,” Toth says, “we asked, ‘How can we integrate sustainable food production with conservation?’”

The answer was already there in the forest: Theobroma cacao, the native tree that gives us chocolate, the food of the gods.

The Regenerative Cacao Program

Ecuador exported $838 million of cacao in 2021. Most of this was grown in clear-cut plantations with one species of cacao and no forest shade. But cacao thrives in shade, and there is a growing demand for more environmentally friendly, shade-grown cacao.

So, in 2020, TMA launched its regenerative cacao program, which supports farmers to grow cacao along with native shade trees and fruit trees while following organic principles like avoiding herbicides and pesticides.

To get them started, TMA pays farmers $4,500 per hectare ($1,821 per acre) over five years via monthly cash payments, a subsidy until the farms become profitable. On average, these payments provide about half of the farmers’ monthly incomes.

“TMA did a lot of groundwork to determine how much local farmers earned from unsustainable cattle ranching,” Scott Stone, director of Lookfar Conservation, an organization that advises philanthropic foundations and NGOs like TMA, tells Mongabay. “Then [TMA] created an agroforestry program that … earns these farmers more long-term income while increasing food security.”

A vital part of the program is ensuring farmers can sell what they grow, so TMA also gives farmers access to premium markets where they can sell their cacao at top dollar.

“Knowing I can sell the cacao is the most important part of this,” Wulvio Murillo, a local farmer, tells me on his porch in Camarones, the small town downstream of the reserve. A former cattle rancher, he was the first to join the regenerative cacao program in 2020. “It’s better work than raising cattle,” he says.

One of those top-dollar cacao buyers is To’ak, an Ecuadorian-based luxury chocolate brand co-created by Jerry Toth in 2013 to generate income and create a market for regenerative cacao.

Among To’ak’s offerings is the most expensive chocolate in the world. (Their cognac cask-aged chocolate bar costs $280).

“We saw how people treat wine as an epicurean delicacy and regard winemaking as the noblest of artisanal crafts,” Toth writes. “Why shouldn’t chocolate — and cacao farming — be accorded the same reverence and standards of excellence?”

All of the cacao grown on the farms is considered high-end, “fine-aroma” cacao. Of that, 20% is a rare, heirloom variety known as Nacional cacao, which TMA brought back from the brink of extinction.

This year, 38 families participated in the regenerative cacao program, but TMA hopes to ramp up to 100 families over the next two years.

“Everyone wants in now,” says Alinda Murillo, a local farmer and Wulvio’s sister. She and her brother are also getting along better now, she adds, because they are out working on the farm together and making more money.

For now, TMA cacao is sold only in Ecuador, but they are looking for more buyers in and out of the country. Finding companies willing to buy cacao at higher prices makes the farming program possible, Toth says, but the businesses are doing so only “because there are customers who are willing and able to pay for it and who care enough to read the label and make sure it’s good for the environment.”

For people who want to help protect these forests, one simple way, he says, is “just eat good chocolate.”

Local leadership

The regenerative cacao program is managed by Dany Murillo. Dany grew up just down the road from JCR in Camarones and started working with TMA in 2013 when he was just 16. During the pandemic, when the other members of TMA were locked down in the city, “Dany held it down,” Toth says. “He’s a boss.”

I interviewed Dany from the passenger seat of TMA’s green Toyota truck, speeding down the coastal highway. Here, along the Pacific Ocean, shrimp packing is a primary industry. A skilled shrimp packer makes $450 a month, working long days, but a full-time TMA employee makes more.

As part of his job, Dany visits the farms to ensure they have what they need and follow the program’s rules. On a round of surprise visits to the farms in 2021, he discovered four farmers were using herbicides, which is against the rules. TMA penalized the farmers by halving their payments for a year and worked with them to find better solutions.

This sent a strong message, Toth says, and they haven’t witnessed any more offenses. “We want them to know they can ask for help and that we are here to support them.”

Aside from monitoring, Dany also says these regular farm visits are an good opportunity to learn about the land and talk about conservation. He says it is easy for farmers to connect forests and water.

“Most of the farmers and many others now believe that if it weren’t for the reserves, the water situation would be much worse,” Dany says, “like it is in some other places where they have destroyed forests.”

On our drive, we pass through long stretches of these destroyed forests, cleared for pastures, plantations and housing developments, selling the image of happy, well-to-do families living by the sea.

Our destination is the Cerro Pata de Pájaro, a protected forest about 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) inland from the coast. At its summit are 400 hectares (1,000 acres) of old-growth cloud forest called “the most pristine remnant of Pacific Forest left in Ecuador.”

Pata de Pajaro, water and biodiversity haven

Where the road ends and the footpath begins, we are greeted by our guides for the day, Carlos Robles and Pablo Bermudez, formidable naturalists and park rangers in the Pata de Pájaro (PDP).

“Everyone gets their water from here,” says Carlos.

The forest gets its water from the ocean. Water vapor from the Pacific travels on the wind, collects in the foliage and drips down into the soils and streams that supply freshwater to the 75,000 residents of Pedernales and surrounding communities.

“This forest is a water sponge and a filter,” Carlos says. “Without it, we are caput.”

Our hike into the water sponge begins in lower elevation pastures, where we snack on oranges, tiny bananas and the white meat of cacao fruits. After a few kilometers under the sun, we enter the cool, dark shelter of the forest.

Carlos points out a large hardwood tree. A 1-km (0.6-mi) clearing would wipe out every known individual of this critically endangered tree species, he says. The tree, Bauhinia haughtii lives here and nowhere else on Earth. It displays its flamboyant, flamingo-pink flowers on thin branches near the ground, as if in defiance of its rarity.

Several plants we pass are familiar to me from the high-end houseplant boutiques sprouting up in major U.S. cities. The foliage along just a meter of this trail would set you back a few thousand dollars in San Francisco or Los Angeles. The PDP contains four distinct botanical zones within its 4,333-hectare (10,707-acre) area and tens of thousands of plant species.

Past the elite plants and elusive trees, our trek goes vertical, into the old-growth cloud forest. Here is a kaleidoscope of mist-shrouded green, and every step I take becomes a heaving, muddy lunge. While I’m scrambling up a slick patch of path on all fours, Carlos looks back with a smile.

“The forest is protected by its steepness,” he says.

The same path that has me sliding on hands and knees is impassable to the mules and vehicles of would-be loggers. Consequently, this upper forest, with its fortress of steepness, remains a stronghold of diversity amid a landscape of destruction.

Tropical cloud forests, such as this one and the JCR, have been called “terrestrial coral reefs” and are some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet.

According to John Clarke, a research botanist at the Marie Selby Botanical Gardens in Florida, the plant diversity in Ecuador’s Pacific forests is astounding. “Every time we set up a 1-hectare [2.5-acre] plot, we would find trees so unique that they weren’t replicated in other plots. … When we’re documenting the diversity, we’re finding things every day that are surprising.”

TMA took over management of the PDP in 2022 but is working with the local organization that established the reserve in 1995, Fundación Ecológica Tercer Mundo, to safeguard the entire protected area through monitoring and patrols. The top of the mountain is safe, but more accessible areas at lower elevations have seen deforestation in recent decades and damage from roving cattle.

The region faces multiple conservation challenges, including threats to its remaining forest patches due to illegal deforestation near accessible roads, limited law enforcement in protected areas, and inadequate awareness and attention compared with other regions in Ecuador.

After the hike, our crew tumbles out of the forest, drenched from head to toe. Dany laughs when he picks us up in the truck. Back on the road, I ask him about his dream for his home region. He hopes the area will be known worldwide for restoring the forest and growing the world’s best chocolate.

Also, he wants to complete The Capuchin Corridor.

The Capuchin Corridor: Connecting coastal forests for the long run

The Capuchin Corridor is TMA’s long-term vision to connect the Jama-Coaque Reserve and Pata de Pájaro, creating a 43-km- (27-mi-) long corridor that would protect an area of forest half the size of New York City.

The name comes from the Ecuadorian white-fronted capuchin monkey, a critically endangered monkey that lives in these forests. This species, and many others, need large, contiguous habitats to thrive.

To create the corridor, TMA plans to protect all remaining old-growth forests and connect those fragments through community agroforestry and reforestation. Obstacles remain, but progress is real.

The most significant obstacle may be financial. TMA has relied on grants from foundations and private donations, including direct sponsorship of farmers, to stay afloat. However, they will need continued and significant investments to make the corridor a reality.

TMA estimates creating the corridor will cost $17.5 million over the next six years and an additional $6 million over the next 25 years. These figures include buying forested land from private owners, expanding the regenerative cacao and reforestation programs and paying staff.

“This is a pretty good deal to save an ecosystem,” Toth says. “An apartment in Manhattan sells for that much,” he laughs. But the corridor would provide freshwater to around 80,000 people, which you don’t get from a condo in the city.

“This is a true frontline of conservation,” Marc Hoogeslag, senior expert in nature conservation for the IUCN National Committee of the Netherlands (IUCN NL), who is not involved with TMA, tells Mongabay. He says donors often turn away from places like this to favor more well-known and well-preserved regions, like the Amazon. “For smaller NGOs like TMA, it is very difficult to survive. I really admire TMA for that.”

Dany dreams of completing the corridor and walking it from end to end someday. “I know it will take days,” he says, “but then I will be content.”

This dream, he says, seems possible because of the changes and successes he has seen and been a part of over the past decade. He witnessed firsthand how farmers came on board to plant trees and how fast a pasture can start to look like a forest again, bringing life back to the land.

Bringing back the forest

We stop in the forest on the road from Camarones into the Jama-Coaque Reserve. “This is the forest we planted,” Toth says as we exit the car.

This was a pasture 10 years ago, until TMA planted around 15,000 trees. They were still learning how to do reforestation, so about half of those trees died. But in their place, thousands of others grew independently, their seeds deposited in the droppings of birds and mammals visiting this new habitat.

Over the past decade, TMA has been experimenting with a few methods of reforestation to decide which is the most effective. These include actively planting trees, letting forests grow on their own (a technique known as natural regeneration), and just planting a few trees or groups of trees and allowing nature to take over the rest.

TMA records every tree they plant and measures the growth (biomass) of a subset of those trees to estimate how much carbon the forest captures. So far, they have reforested around 149 hectares (368 acres) of land, with plans to ramp up in the coming years.

“We have been really impressed with TMA’s work because of their holistic view of conservation and restoration, as well as their rigorous approach towards quantifying the outcomes of their work,” Leland Werden, a restoration ecologist in the Crowther Lab at ETH Zürich, in Switzerland, tells Mongabay. TMA is now working with the Crowther Lab as part of a more extensive global study on reforestation methods.

Growing cacao under shade trees is also part of the reforestations efforts, accounting for around 31 hectares (76 acres) of forest.

“Cacao agroforestry is a very valid and complementary approach [to reforestation],” Xavier Haro-Carrión, an assistant professor at Macalester College in Minnesota who studies forests in the region, tells Mongabay. “Evidence suggests that agroforestry systems can help to preserve important components of the original biodiversity of a place … [and] help improve forest connectivity.”

Long-term resilience

With the cacao and reforestation programs underway, Carla Rizzo, TMA’s general manager, says she is excited about their new community programs. These include a series of workshops to design and build a playground in Camarones with the help of award-winning architects from Quito.

Twenty-one women and kids came to the first design meeting, Rizzo said, a large turnout for a town of just 217 people. Throughout the workshops, locals said that besides having safe and beautiful places for kids to play, they needed comfortable areas for the adults to spend time together. They want this place to be a haven for women and children; safe from the cartels, violence, alcoholism and sexual assaults that threaten this and many other communities.

The community and the architects had lengthy discussions about what “safe architecture” looks like, Rizzo says, and they are working to incorporate as many of the women’s ideas as possible. Future workshops will focus on design and build, logistics and finances, and TMA plans to involve the community in each phase.

“The [Jama-Coaque] Reserve and the Capuchin Corridor are not going to belong to us forever,” Rizzo says. “Right now, we are the guardians of this place … but our bigger mission is for the local community to be the guardians. … I’m noticing that some of the little kids are very aware. They do care about this place.”

Clarke, the botanist, says he has watched conservation organizations operate in the region for 30 years, and having good relationships with communities is the key to success. “What I know about TMA is that they have a good relationship with their neighbors, and I think that’s probably going to hold more weight in the long term than anything else.”

Little candles

Back in the JCR, I sit with Toth next to a waterfall, which flows into the clear, cool stream beside us. We watch as a family from Camarones ambles upstream, carrying shrimp in a small net. It’s dinner for tonight, they tell us, holding up a few pounds of fresh-caught crustaceans. This forest belongs to everyone, Toth tells me.

“Sometimes, I sit here and think that protecting just this reserve is enough,” Toth says. “But then I think about the whole corridor and imagine all the places like this spot that we can protect, and I know we have to keep going.”

“These patches of forests are like little candles in the night,” he says. “We can’t let them flicker out.”

Banner image of a baby howler monkey in the Jama Coaque Reserve by Ryan Lynch.

Ecuador court upholds ‘rights of nature,’ blocks Intag Valley copper mine

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page