Curator Aindrea Emelife talks to Ashleigh Kane about her radical new show about Black femininity, opening at London’s Somerset House later this month

Sandro Botticelli’s 15th-century painting, “The Birth of Venus”, has long been regarded as the apex of female beauty. But there are only so many women who can relate to a naked blonde woman, birthed from sea foam and emerging from a giant clam shell. Women who don’t see themselves reflected in Venus’ narrow image have had to reckon with problematic representations stemming from racism, othering, misogyny, sexualisation and fetishisation.

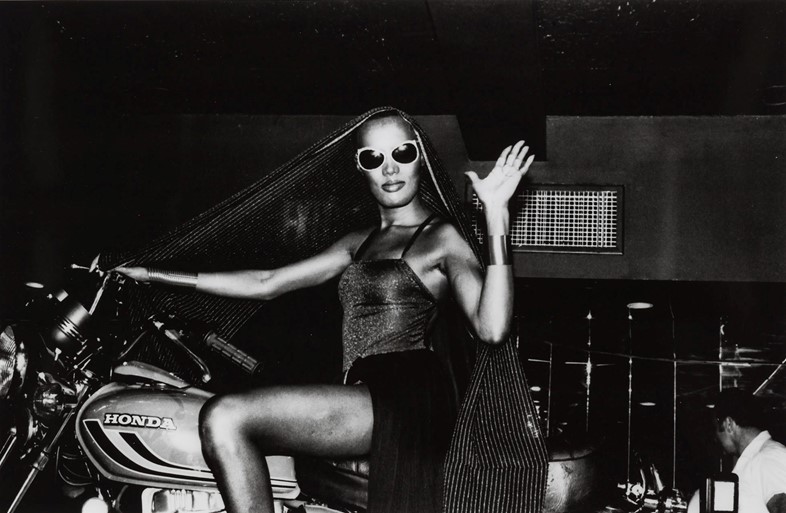

BLACK VENUS, an exhibition opening at Somerset House on July 20, counters this by showcasing the plurality of Black femininity. Curated by Aindrea Emelife, BLACK VENUS celebrates the pioneering works of 18 women and non-binary artists, including Carrie Mae Weems, Renee Cox, Sonia Boyce, Zanele Muholi, Ming Smith and Lorna Simpson, as well as an emerging generation of artists building on their legacies. Three archetypes lay the foundations for the show: the Hottentot Venus, the Sable Venus, and the Jezebel dating between 1793 and 1930. Each is used as a departure point to examine the depictions of Black women throughout visual culture, while bringing forth alternative images of femininity true to the Black women and non-binary artists behind their making.

As the show prepares to open – with tickets priced as pay-what-you-can – Emelife speaks with Dazed about the show’s personal significance, whether these depictions have changed over time, and the poignancy of the show.

Congratulations on the show. BLACK VENUS tackles an evolving topic and an ongoing conversation. It must be hard to draw a line when so much new work or ideas constantly surface.

Aindrea Emelife: There are endless things to add. It’s a huge topic with an expansive history and storytelling that, as you’re saying, hasn’t been touched on. I think about the exhibition, and the book, as a catalyst for further investigation. [I’ve included] some artists who haven’t been regarded for a while but who I consider important. There are non-binary perspectives because, where there are great Black feminist discourses and Black women discourses in art history, because of the timings of those ideas, there’s not always an inclusion of those perspectives. I didn’t want to fall into the trap of just thinking about the normative female body, so I used the word ‘woman’ rather than ‘female’, as ‘woman’ feels all-encompassing and ‘female’ feels too rigid.

Was there a moment or experience that sparked the idea for the show, more specifically?

Aindrea Emelife: It’s something that’s been in me for a while. When I was seven or eight years old, my mum taught me the story of the Hottentot Venus. Even though I probably brushed it off at first, it stuck in my head at some level, and it popped up a lot throughout many steps in my life.

As I grew older, I started to understand the makings of the world, whether gender politics or how Black women are seen, and these stories became very impactful and a way to understand all of the Black womanhood before me. For several years, I’ve been very curious, reading and researching topics related to this story, whether about Jeanne Duval, Baudelaire’s mistress who was painted regularly by some of the Impressionists, or looking more at the Hottentot story, or trying to find incidences of the Black woman throughout other art historical periods.

It all crystallised a few years ago when I came across one of Deborah Willis’ texts while thinking about the representation of the Black woman in realms of visual culture, whether music videos or fashion, which are other puncture points throughout the exhibition. As you noted, there were, of course, other shows that looked at Black women, but nothing that spoke pointedly about agency, which I have found very central as a curator, but also how I wanted to move in the world as a Black woman. I was asking, how can I reclaim my agency to be who I am without restriction?

Why did she tell you the Hottentot story?

Aindrea Emelife: My mother was always interested in Black and African history, and I think she was reading about it and wanted to tell me the story. I wasn’t going to be taught about these types of stories at school, so I think it was a sense of building the awareness that there’s more than you’re told, which became part of my curatorial practice.

The Hottentot Venus is one of three archetypes that the show is guided by. The others are the Sable Venus and the Jezebel. How do those two come into play in the show?

Aindrea Emelife: The Sable Venus is another catalysing moment. It’s this incredible etching of Botticelli’s ‘Birth of Venus’ but replaced with the face of a Black slave woman. It’s a fascinating and emblematic image looking at the perceptions of beauty and idolised beauty.

Throughout art history, Venus has been an emblem of beauty: porcelain skin, blonde hair, birthed from a shell. Replacing that image with the Black woman allows us to question what the world would be like if our icons of beauty in art history, which feed into a wider visual culture, were more expansive. What if there were more examples of Asian women or Black women? It also looks at colonial ideas of Black women and allows us to understand how they were seen.

The ‘Black Venus’ was almost seen as an impossibility. Even though I’ve chosen to use the title as an empowering phrase, historically, it would have been laughable because a Venus could never be Black. It’s almost a parody of the concept. The phrase is a reclamation, saying, of course, a Venus could be Black.

The Jezebel feeds into the same idea, which is the sexualisation of Black women, which starts with the Hottentot Venus and then shifts into colonial ideas and very harsh truths about how Black women were seen when enslaved. It also seeps into more recent aspects of history, whether it’s looking at how Black women are sexualised in more contemporary spheres or the exoticisation of Black women and their association with otherness or ‘tribalness’, or with a gaze afforded to other women. What’s great about the contemporary artists (in the show) is that many confront these narratives head-on and take on the emotional labour of looking at these uncomfortable ideas and how they still come up in contemporary life.

“The ‘Black Venus’ was almost seen as an impossibility. Even though I’ve chosen to use the title as an empowering phrase, historically, it would have been laughable because a Venus could never be Black” – Aindrea Emelife

Many of the works in BLACK VENUS are photographic, was that a choice due to the politics of the camera?

Aindrea Emelife: It was a pointed choice. Photography allows us to understand the early agency of the Black woman in history. There’s something so interesting about photography and who holds the camera that is so immediate and all-encompassing. In the London exhibition, I still strongly focus on photography, but I’ve added other modes of creativity and visual culture. There’s installation work, film work, and a few paintings, so it’s more diverse in medium, and that was a natural progression to look at a wider scope of how artists are making today.

I was also inspired by a few key artists at the beginning of my research, such as Carrie Mae Weems and Renee Cox. But also into non-women artists like Frederick Douglas and how he wanted to be the most photographed Black person, and how in that activism, there’s a sense that the more you’re seen, the more visibility that’s afforded to a person or type of person, the more that impacts the world at large. I think that’s also the power of photography.

Photography is almost a more democratic way of seeing that I think is a really important lens for this topic. There are examples of fine art photography and a few instances of fashion photography, and the mixture of those two subcategories of photography allows us to understand the shifting or subliminal messaging that photography has in our daily lives and how these artists create counter-narratives.

Lastly, the show is really a who’s who of incredible Black women artists. It’s so exciting to see. How did it feel to work with these artists?

Aindrea Emelife: It’s one of the best things about this job to interact with artists I admire and who have been so central in my making as a curator has been very humbling. The other thing about the exhibition is it’s very close to my own story and experience, and that makes it more sentimental and spiritually moving: it’s about the Black woman in art history, but by curating it, I’m learning more about myself daily and how my story fits into the exhibition.

Having these artists coming together multi-generationally and geographically will show just how big, boisterous, and expansive all these stories and ideas are. It was important to be multigenerational because I wanted to understand the progression of time and sensibility, and also the lack thereof. It shows the nuances of exoticisation, fetishisation, and sexualisation of the Black woman’s body change only by the subtleties of society. Whether it’s the Hottentot Venus, a pop star, or someone in our contemporary life. When you see the exhibition, you’ll understand the passing of time, but not the passing of perception – just a refashioning of it.

It’s not just important for us to understand how expansive Black women’s history is and has been, but it proves there’s so much about the world we don’t know and haven’t been shown. Even if you’re not a Black woman or a woman, going to the exhibition, seeing artists wrangling with and articulating this takes the blinders off. You will start to understand that, wow, it’s 2023, and there are still so many other strands of history and experience that we haven’t tackled.

BLACK VENUS runs at London’s Somerset House from July 20 until September 24

Join Dazed Club and be part of our world! You get exclusive access to events, parties, festivals and our editors, as well as a free subscription to Dazed for a year. Join for £5/month today.