This story originally aired in the Nov. 26, 2023 episode of Inside Appalachia.

Square dancing has long been a tradition in Appalachia, and many communities throughout the region still host regular dances. Square dance calling — the spoken instructions said over the music — makes participation easy. But there are other aspects — like the prevalence of gendered language such as “ladies and gents” — that can make square dancing an unwelcoming or confusing space. One group of friends in the Appalachian square dance scene are taking action to make the tradition more welcoming for all participants.

The Augusta Heritage Center in Elkins, West Virginia has been hosting square dances for decades. During their annual Old-Time Music Week in July, their outdoor pavilion is decorated with twinkle lights and paper lanterns that sway in the warm summer breeze. Dozens of couples gather and follow instructions from callers like 25-year-old artist and Elkins resident, Nevada Tribble.

Unlike the square dances you probably did in gym class, Tribble’s calls have no gendered language — no “ladies and gents,” and no “swing your girl.” And this is on purpose. Before she learned to call square dances, Tribble grew up dancing in Elkins.

“We always had the kind of dance scene where everybody dances with everybody,“ Tribble said. “You change partners after every dance regardless of who you came with. And I think that was also a part that made it really inviting and inclusive.”

Tribble noticed that the language of the calls didn’t necessarily reflect the people on the dance floor. Sometimes there would be an uneven ratio of women to men on the floor, and using “ladies and gents” didn’t make sense. Some folks might want to dance with a same-gender partner, whether it’s a spouse, a friend or a kid. And, of course, there might be dancers who don’t identify with being called either a “lady” or a “gent.”

Tribble thought everyone would feel welcome if callers used gender-free language. And by making sure there are calls any gender can dance to, the caller helps keep the dance floor full.

Credit: Lydia Warren/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

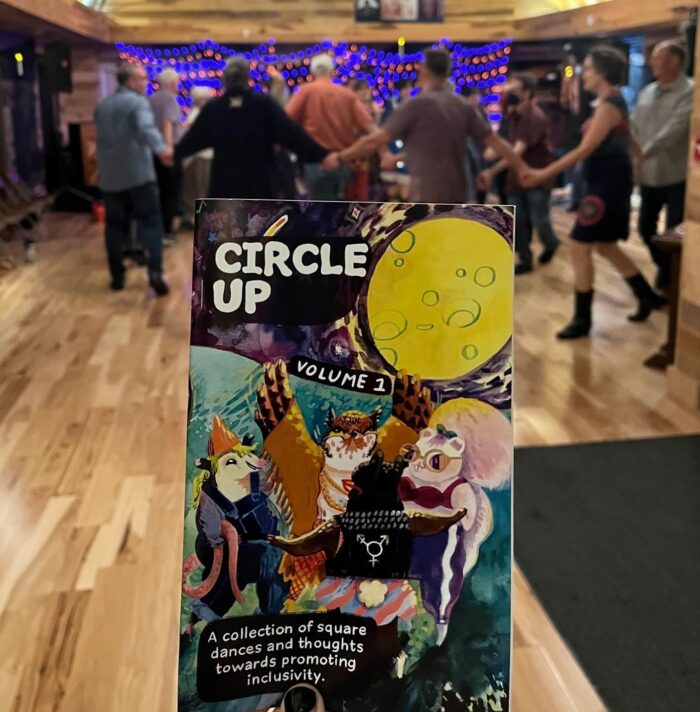

Tribble is part of a new wave of callers in the Appalachian square dance scene who are trying to make dances more welcoming by using gender-free language, as well as offering some seated and no-touch dances for participants who prefer or need these accommodations. They are sharing their new calls in a zine called Circle Up. The zine is a small glossy booklet with hand-written and illustrated instructions on how to call 17 inclusive dances.

Circle Up was curated by square dance caller and professional dancer Becky Hill, who mentored Tribble when she lived in Elkins.

“This zine just feels like it’s a large invite. Like, here are some people that have some idea,” Hill said. “We’re not claiming to be experts. We’re not claiming to be the only way forward. We are just the ones who have decided to start this conversation and to be a little bit more loud about that.”

Credit: Lydia Warren/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

For Hill, creating a welcoming space isn’t about losing touch with the tradition. It’s a matter of bringing out aspects of the tradition that are already present.

“We don’t have to change ‘chase the rabbit, chase the squirrel.’ We don’t have to change ‘birdy in the cage.’ We don’t have to change all these things,” Hill said. “It’s just providing options and invitation to callers to just think about ‘Can I just simply get out of the habit of saying swing her,’ or ‘gents to the center.’ You know, are there ways that I can just slightly adapt it and it becomes a little bit more warm?”

Credit: Lydia Warren/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

Of course, making square dances more welcoming is about more than just gender and language. It’s also about race. Musician, dancer and community organizer A’yen Tran has been working on creating safer spaces in the scene.

“The square dance community, or the old-time traditional music community, is pretty white,” Tran said. “The music does not come from entirely white roots. The banjo comes from Africa. There are fiddles in Africa, also. And the people in the community are still overwhelmingly white.”

Tran said she did a survey of people in the traditional music and dance scene and found that some people did feel unwelcome at jams, dances and festivals. She formed a diverse group including people of color, trans people, an indigenous person and a white male, among others.

The group created a set of community principles. They include guidelines like not using slurs and listening to others. These principles were illustrated and printed into a poster which is tucked into Circle Up.

“Our hope is really that people will take the principles, use what’s valuable to them in their own communities,” Tran said. “Bring them to your local square dance and stick them on the wall, or bring them to your local folk school and stick them on the wall, or your event, or if you have a camp at Clifftop or Galax or whatever festival you go to. You can just clip it up and say, ‘’This 10 by 10 space is my safer space that I’m welcoming people into, and these are the principles that we are going to try to stick by in order to make this a more welcoming community.’”

Tran, Hill and Tribble are excited to see square dances become more welcoming and, in turn, grow into spaces where even more people feel at home on the dance floor.

——

This story is part of the Inside Appalachia Folkways Reporting Project, a partnership with West Virginia Public Broadcasting’s Inside Appalachia and the Folklife Program of the West Virginia Humanities Council.

The Folkways Reporting Project is made possible in part with support from Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies to the West Virginia Public Broadcasting Foundation. Subscribe to the podcast to hear more stories of Appalachian folklife, arts and culture.