The creator of Overlooked, which writes the obituaries for remarkable people in history, shares the inspiration behind a new limited series.

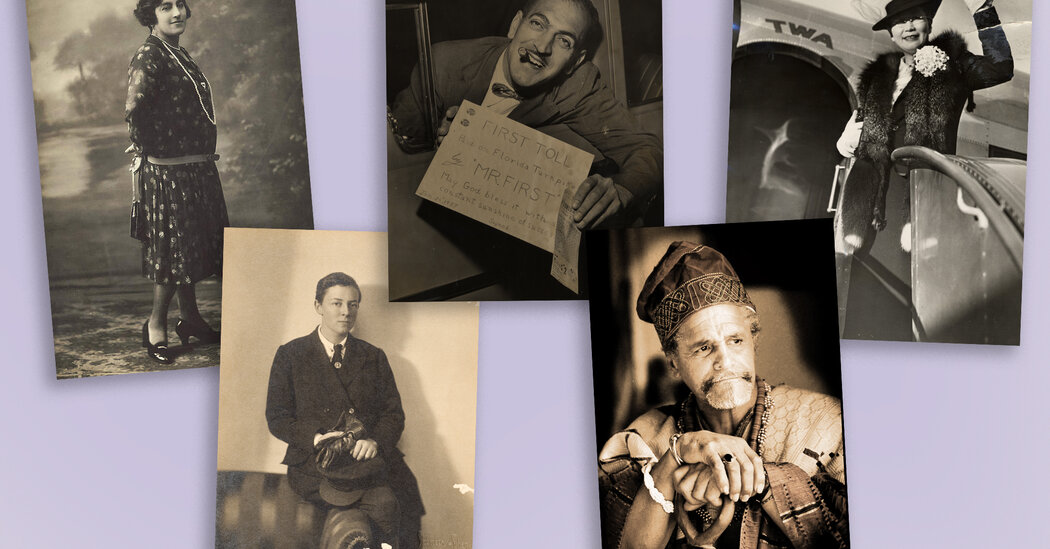

For more than five decades, whenever a new bridge, tunnel or highway opened in New York City, Omero C. Catan made it his business to be the first person onto, into or along it.

In 1951, Catan, a vacuum cleaner salesman by trade, became the first motorist to ride along the New Jersey Turnpike; in 1953, he was the first straphanger to use a token on the newly opened Eighth Avenue subway line in Manhattan; and in 1955, he was the first person to drive across the old Tappan Zee Bridge.

His 537 firsts, by his own count, earned him a nickname in the national press: “Mr. First.”

Catan, who was born in Brooklyn into an Italian American family at a time of pervasive anti-immigrant sentiment, didn’t let his circumstances define him. Rather, he built his legacy as a professional “firster,” spending frigid nights in his car while staking out new infrastructure projects. (He achieved firsts outside of transit, too: In 1939, for example, he received Manhattan’s first marriage license of the year, The Times reported.)

His life is one of several that will be remembered in a new limited series from Overlooked, a New York Times franchise that shares the obituaries of remarkable people in history whose deaths were not noted by the newspaper at the time.

I began developing Overlooked in 2017 as a way to help correct the balance of history by recalling the lives of women, people of color and others who made significant contributions to our society but were left out of The Times’s narrative.

Since the first Overlooked article was published in March 2018, dozens of writers, editors, photo editors and designers have come together to publish more than 200 profiles of activists who risked threats to their lives to fight injustices, artists whose work has endured through the ages, adventurers whose feats captured imaginations and many others.

This new limited series, however, will focus on perhaps the most notable of notable people: firsts. People like Margaret Chung, the first known American woman of Chinese ancestry to earn a medical degree in the United States (her obituary leads off the new series); Alice Anderson, who ran Australia’s first all-women car-repair garage; and Adefunmi I, who was king of a one-of-a-kind village in South Carolina that he created for practitioners of the Yoruba religion.

The series reveals how people have reached deep down for the bravery necessary to ask questions no one had asked before, how they channeled their curiosity and innovative spirit to shape the way we live. Sometimes they did it for the spotlight, as with Catan, but others were following their deepest beliefs.

The new series will appear periodically in the newspaper beginning this week — the 172nd anniversary of when The Times published its first newspaper in 1851.

This November will bring a first of my own: I’ll become a first-time author with the new book “Overlooked,” which seeks to broaden society’s historically narrow lens by telling the stories of extraordinary lives that have been hidden from view. It includes around 200 photographs and 66 obituaries, nearly half of which — including the ones in this new series — will be new.

As an editor on The Times’s Obituaries desk and the curator of Overlooked, I often think about whom we deem worthy of including in the paper of record.

Sometimes the decision is obvious: major political figures, Oscar-winning actors or chart-topping musicians, for example. But usually it’s a challenge. With every name that comes across our desk, we ask questions: How did this person leave a mark on the world? Did he or she change the way of life for a group of people or society at large? Is there simply an interesting tale that would enlighten our readers?

Overlooked has guided us as we ask those questions, too, by showing us that sometimes people weren’t given equal opportunities to make a difference, but they broke through barriers nonetheless. And their stories deserve to be told.

While we will never be able to recount every single life, I hope that this work allows us to continue to expand our notion of whom we, as a society, deem as worthy.