Since graduating from Central, she has no regrets.

“I got this right, and why should I pass [on] the best high school in the state of Arkansas. Why shouldn’t I go there?” she said.

Then she went on to graduate from what is now the University of Northern Colorado, on whose board she now sits. She fell in love with Colorado’s natural beauty and has made her home here, raising scholarship money and mentoring students.

Of her participation in the protest that integrated schools and was a precursor to Black and white children learning together, she said: “It’s a part of my life. It is not my life. We go through stages. And we’re still here. We did the best we could with what we had.”

And now, she watches her legacy in the actions of others.

“What makes me feel good is to see young people who have taken advantage of the opportunities to get the best education available to them to move it to the next level,” she said.

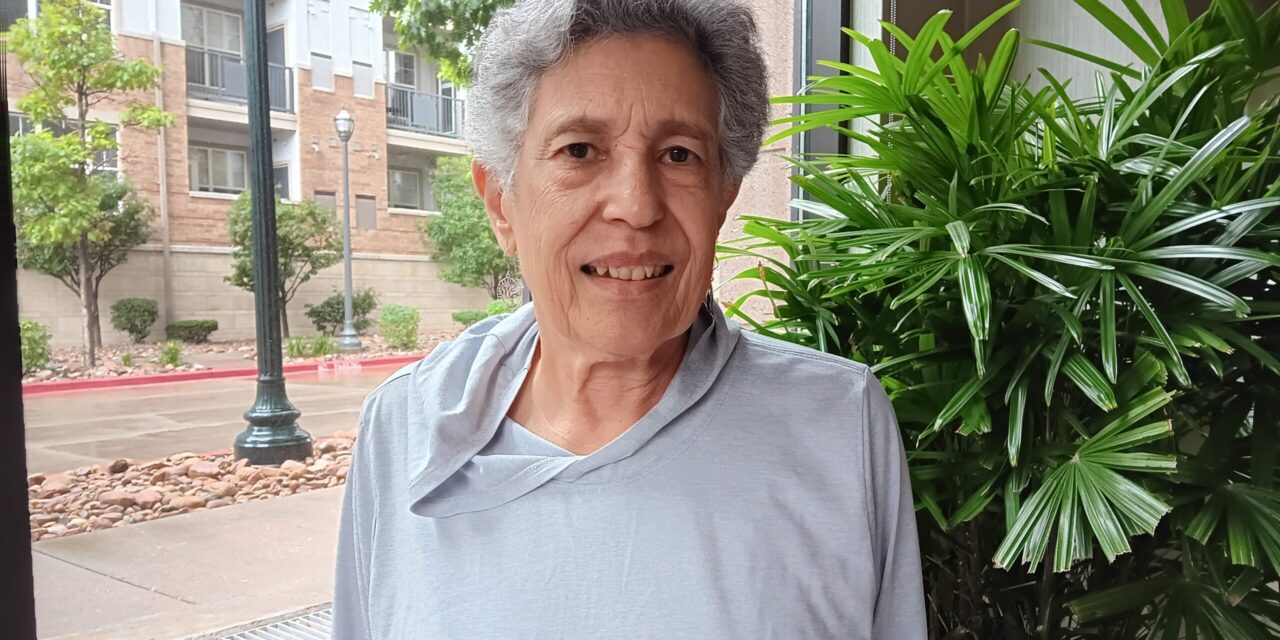

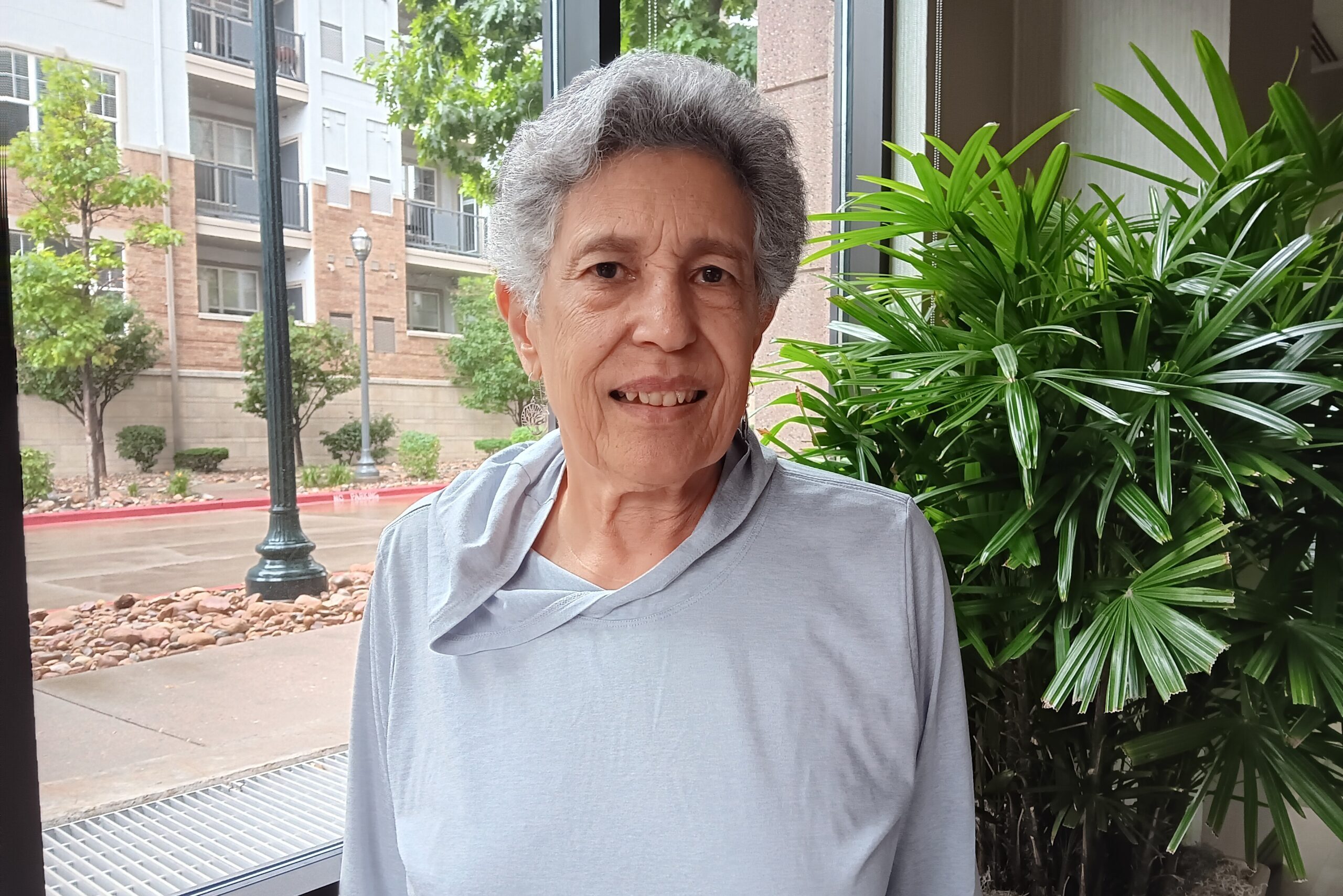

Below are the highlights of a 47-minute emotional interview with her shortly after she learned of Huckabee’s efforts, which, she believes, will not have a bearing on the truth of the piece of American history she was a part of — visceral memories of which still touch her today.

Read the interview

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Elaine Tassy: What are your thoughts and feelings about what’s happening in Arkansas right now?

Carlotta Walls LaNier: I just thought it was ridiculous. I got a phone call regarding that. My cousin actually teaches the AP course there at Little Rock Central High School, and is well-certified to teach it. And she explained to me the things that were happening there. It’s unfortunate that we are now going back more than 60 years and repeating history again. It is mind-blowing to me that the governor would make this statement when she took the “Little Rock Nine 101” course at Little Rock Central High School herself. So I don’t know what is all behind all of that. I live here in Colorado. But the course will be taught. And they have been guaranteed, as far as the universities in Arkansas that are state-supported, that they will accept the credit for the AP African-American studies course. So to me, that’s kind of interesting that the state-supported schools will accept the credit which is being funded by the state. So it is mind-blowing.

So what you’re saying is that even if a student graduates from high school and can’t receive credit towards their high school graduation for taking AP African-American Studies in high school, the college will…

The college will accept it. And the college board across the country is accepting it. So none of this makes sense, as I see it. And then there’s the other piece that we have to talk about, that there’s a need for African American studies as a part of the curriculum in all schools where all kids have the opportunity to learn about other groups of people. I asked the instructor, “What is the makeup of your 150 students that you are teaching this AP course?” And it is a mixed group of people. There are white, brown, Black kids wanting to learn that piece of American history. You shouldn’t take those sorts of things away.

Unfortunately, our school systems are taking away things that help to make you a better person. I think that civics and history needs to be required for any kid to graduate from high school. Humanities need to be a part of your curriculum. And I’m finding that a number of states, especially southern states, are passing bills to stop books from being read. There’s banning of books. Everybody needs to know which books are being banned and go out and read them, is the way I see it.

What do you think about the argument that it causes people to hate each other and themselves?

They don’t know about themselves evidently. They shouldn’t hate themselves. Once they get to understand their worth and their value and what their forefathers have done here in this country, they will have that worth and understanding. And that also goes for white and yellow and reds and whatever here in this country. Once you know your history, know who you are, you have value. You show your value. You want to talk about with others to have them understand and learn about your background and your family background. And that helps to make what is called the United States of America. So that is how I see that.

How I’m seeing this whole thing right now is that I felt sorry for those white kids when I was going through what I was going through at Little Rock Central High School. I considered them ignorant.

So you felt sorry for them because they were being vicious towards you?

Vicious and not understanding that I was their equal. They did not accept me as their equal, but I knew I was their equal. So yes, that’s ignorance the way I see it. And I see it that way today. This is just plain ignorance. And if they want to continue to go down that path, that’s the road they’re taking right now, they’re not learning. And every child should have the opportunity to learn. I don’t care who you are. Everyone should have that opportunity. So no, I didn’t hate them.

Even though you could feel that they hated you.

Even though I knew they hated me. I was not taught to hate. And I hope that I have been successful with that with my children, not to hate people.

Speaking of your own children, will you tell me a little bit about what your life became after your experience in Little Rock?

Well, for 30 years, I didn’t talk about that, about that experience. It was too painful to reiterate, and I really didn’t want to talk about it. I didn’t want to relive it. So it was not until the 30th anniversary that we all gathered for the first time in 30 years, that we saw each other. And it was pretty much after that the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) had their annual board of directors meeting in Little Rock in 1987. They invited us there and we all came, and it was quite a moving event for us.

And since 1987, you’ve been speaking about it more publicly?

Yes. It took me probably a good 10 years to be able to, or more. To be honest with you, once I wrote my book, that was the most cathartic part for me. And I was able to get it down. And since then, I can talk about it much better than I could before.

What were some of the parts of it that you found to be really difficult and painful to discuss?

Well, all of the hate and so forth that took place, the deaths that took place. I didn’t realize I had flashbacks when I was talking to the youth about this time in the various history classes that I was asked to come and speak to. And all of a sudden, some of what I had pushed to the back of my mind was coming forward. One in particular I was telling them about was when the chief of police and his wife were killed. They (investigators) said he killed his wife and then killed himself. I never believed that. I just know that they were murdered because he was one of the people who was trying to be an assistant to us. He would give us information about not being in a certain part of the school at a certain time because they had infiltrators there. So he was helping. He was being a law officer, as they should be. And as I was telling that, I all of a sudden broke down and I had to leave the room. So those are the sort of things when you have these flashbacks. Sometimes you can deal with them, and sometimes you can’t. And I couldn’t that day.

How did you end up living in Denver?

I went to Michigan State University when I finished high school. And I had an uncle here who would write. He was telling me how great it was here in Denver. So I came to visit between my freshman and sophomore year. And then I went back to Michigan State, and I could not get this place out of my mind.

What about this place could you not get out of your mind?

It was clean, the mountains, the blue sky. When I arrived, it just felt right. And I’ll never forget, I was walking down 17th Street. And you know how it is downtown, all this was all new to me, and I asked for directions. I saw a policeman at the corner, and I went up and asked how to get to where I was going, and he gave it to me. And I crossed the street, and it hit me that I never would’ve done that in Little Rock, Arkansas.

I’m assuming it was a white police officer. If you had done that in Arkansas, what do you imagine the outcome would’ve been?

I never would’ve asked. We had Black policemen, but they were in Black neighborhoods like what we call Five Points today. When I came here, Five Points was predominantly, or 90% African American. Things have changed since, but that’s what it was when I came here in 1962. So I’ve been here a long time.

And so what have you done since 1962 here in Denver?

I finished college at what is now the University of Northern Colorado. I then worked for four and a half years for the YWCA as a metropolitan Denver teenage director. One of the jobs I had was to renovate a home that had been given to the Y. And as I did that with volunteer work, I recognized that I grew up in that business. My great grandfather was the first Black contractor in the state of Arkansas, and my father was a brick mason and I was around construction all the time. And I decided to get my broker’s license. I did that, and I’ve been in real estate ever since. I used to be on various boards here in the city, or here in the state of Colorado. I get involved in community work. I’m a worker. I discovered that after being on boards, I’d rather do some of the work than to be sitting in meetings all day.

I’m the same way. So you also mentioned that you had some children. Do you care to share a little bit about your family in Denver?

I have two grown children, and each has given us a grandchild. I have a granddaughter who’s the oldest of the two, and that’s my son’s daughter. And my daughter gave us a grandson who is eight.

What year in school is your granddaughter now? And is she getting the type of African-American studies education that you think she should be?

I do not think she’s getting that at school. But being around me and some others, she will get it. So my grandson, when he was seven, invited me to come and speak to his second-grade class because he’s read my book, and he wanted his school or his classroom to understand who his grandma is.

Today, I say that everyone has a responsibility, and especially in the African American community, to speak to their children, their grandchildren, their nieces, nephews, sisters, brothers, whatever, and help them understand what they and their forefathers have given to this country. I knew that growing up. That was part of the conversation within my family. My mother and father both came from pretty large families, and my mother’s side of the family had more educators. My father’s side of the family were more entrepreneurs that had businesses of their own. Whatever they did, they did on their own, owned their business. All believed in education. And as I said before, even at my Black junior senior high school, before going to Little Rock Central High School, I had three relatives there that were teachers, one who was over the library, one who taught auto mechanics, and another who taught physical education. And then there were a lot of friends there that were friends of my family.

Well, I heard you talking with my colleague Ryan, about how when you were in junior high school, you got to be involved in a lot of different activities. You got to really shine and do the sorts of things that you wanted to do. So when you were in high school, were able to participate like you wanted to do?

No. High school was 10th, 11th and 12th for me. I knew going in that we were not going to be able to participate in any extracurricular activities, that we were told that by the superintendent of the schools the month before we started. So I do believe that the 39 (potential students) that were in that room heard that and decided, ‘Well, maybe this is not the place for me.’ Because I know for myself, and those, the others of the Little Rock Nine, we were always taught that to be a well-rounded person, you do well in school, you participate in activities, you do for your community, you’re church-going people, and that sort of thing. I think that the 39 in that room with the superintendent had passed the “Jackie Robinson test” in a sense, and these were safe kids to go to Little Rock Central High and be a part of an integrated situation.

Can you explain what you mean when you say they passed the Jackie Robinson test?

Well, we all know what it took for Jackie Robinson to be… He was the first to play professional baseball. That’s not to say that he was always the best, but look at how old he was when he finally got that opportunity to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Jackie Robinson was told that things are going to happen, and you are going to have to be able to ignore it and be able to move past that, in so many words. And I think that we were that way. We knew when we were told that we could not retaliate, we understood that, but we weren’t those types of fighters. You got physical fighters, and then you got mental fighters, and I think we were more of the latter.

So take me for instance. The way I protected myself in the hallways was understanding that once they had knocked my books out of my hands as I walked down the hall, and then I had to stoop to pick them up, after the first kick in the rear, I recognized I had to keep my rear to the wall. When I was in the cafeteria, you knew that you had your back to the wall. So it was a defensive mechanism that I developed that particular year. And it only took one something for me to not want to have to repeat it. So I’m sure Jackie Robinson went through the same thing with the information that he had been given before he started playing in the major leagues. And I know he got angry. I met this man when I was a kid. I’m sure he was angry about some things, but he had to restrain himself for a lot of activities.

So if you had the chance to do it again, would you choose to?

Yes. I used to say no. I didn’t actually say no. I used to say if I didn’t have family, because they are the ones I felt that suffered the most. But as I’ve grown older, that was a flippant remark because we all have some type of family. We come from somewhere. So the more I thought about it, don’t be flippant with it. So would I do it again? Yes, because I know it was the right thing to do. What I was doing was within the law. And I had been taught from early on that the best way to handle things, especially in the south, is that you stay within the law. That was your first move. Were you rightful? And Brown versus the Board of Education gave me the right. The Supreme Court decision gave me the right. The Little Rock School Board abided by the Supreme Court decision by putting a plan in place to exercise that right. I might not agree with the plan that they put in place, but I took advantage of the plan that they put in place.

So if you had wanted to, you could have attended an all Black high school instead?

If I had wanted to, that’s exactly where I would’ve gone, to Horace Mann High School. But no, I got this right. And why should I pass the best high school in the state of Arkansas that had everything that was necessary for me to apply for any college throughout the United States? Why shouldn’t I go there, or walk another two miles to the Black high school? So there was only one high school that was integrated. They built a new high school on the west side of town and a new high school on the east side of town. That’s where the predominantly Black people lived, on the east side. The predominantly middle class and upper class lived on the west side of town, and Central was a little less than a mile away from my home. So why shouldn’t I go there?

So that became the third high school. It was the high school in town, and in the state. The other two were just built. That was a part of that plan. Okay, we got to integrate, but how are we going to do this? And I guess the superintendent and the school board had come up with a plan to build two new high schools. So my best friend refused to go to Central, who lived in my neighborhood. She said, “Why should I go there when I can go to the new Black high school?” Because it was new. Okay? But I didn’t need my best friend to go to Little Rock Central High School. We remained friends and she kept me up to speed of what was going on and all of that sort of thing.

Do you think she had a better experience in high school than you did?

Well, she had a safer one, for sure. I don’t know how we would define better. Mine was a job every day. They took all the fun out of going to high school. I enjoyed school. From kindergarten on, I loved going to school, and I love participating in things. And all of those things had been taken away. So it was all about doing well in my classroom, keeping my honor society level up to be able to go to whatever university that I could get into, with a scholarship hopefully. And that was my goal. And my goal was to finish, be a sophomore at Little Rock Central High School and graduate in 1960 from Little Rock Central High School. And I accomplished that.

And so tell me this, now in 2023, what are the memories that stick with you the most about your high school experience?

The celebrations recently, since the 30th, I guess, have always been on the plus side. I liked the fact that the 40th anniversary, the city decided they needed to clean up their act, more or less. And the committee included the business people that helped to put on the 40th anniversary. And that was a very moving event for us too because the president of the United States was there, along with… He brought his cabinet with him, and there were over 10,000 people out there to celebrate the fact that, for this 40th anniversary. Since then, we’ve had the 50th. That was my biggest memory on the plus side, because after 50 years, we were all there still together. We had all accomplished our various avenues of work and so forth.

We were able to bring our families there and share our stories with the families and so forth. And we gave our scholarships, $10,000 scholarships to nine students to go to college. We had raised close to $1 million. And over a period of time, that is what we did. We set up a program for them, we mentored them that year, and their charge was to mentor the next scholarship winner. And that’s what has happened. In the recent years, it is now a part of the Clinton School of Public Service, where to get a postgraduate degree, we found that they are also in need. So that scholarship fund is there now. We are getting to the point where we can’t handle that anymore as far as raising funds, and so forth. We are in our 80s now. We need to, we would like to sit back, but with what is going on today, we still have to speak to people like you.

Well, what I was going to ask you next is what would you like to say if you had a chance to speak to Governor Huckabee Sanders about the fact that your own personal story is kind of being erased from history? If she would have her way.

If she would have her way. But our personal story will not be erased because we will continue to speak the truth. It’s sad that she has decided to go in that direction. She wants to say that her father opened the door for us. Yes, he was invited by President Clinton, along with the principal of Little Rock Central High School. The three of them opened the door for the Little Rock nine to go through at the 40th anniversary at his request. That is during the days when Republicans and Democrats could talk to each other with civility. Today, it is lacking. And it is unfortunate that they cannot work together across the aisle. There are some that are working across the aisle. I recognize that. But as a rule of thumb, in the past 10 years, it has been very difficult for Congress to represent us as they should when we send them there. So we are fortunate, here in this state, that we have overall, other than one, who I hope will be defeated here in the near future, that truly represents this state.

Do you think that being one of the Little Rock Nine was the most impactful thing that you got to do with your life?

It’s a part of my life. It is not my life. We go through stages. And I do think that the nine of us had a job to do, and we did it. Okay? And we are still here. And that just says to me that we did the best we could with what we had. So what makes me feel good is to see young people, especially those of color, who have taken advantage, the opportunities to get the best education available to them, move it into the next level, whether it is universities or whether it is being a technician of some sort. You don’t have to be a doctor, lawyer, or an Indian chief. You can be the best mechanic. You can be the best plumber. There are other avenues with jobs to make a living, an honest living to take care of you and your family. So to do that and to really appreciate those sorts of things makes me feel pretty good.

What is your day-to-day like now?

I am still a realtor. I do a lot of speaking engagements. During COVID, I had to do them via Zoom. I speak to high schools and to various groups of people, because the book that I wrote in 2009 still has legs and people want to hear more about my involvement at that time. So I do that. I’d like to just sit back and truly enjoy the rest of my life with traveling and listening to great jazz musicians and going to winning football games of the Denver Broncos and the Denver Nuggets. I’m a sports enthusiast. So those are the sort of things that I’m doing. I thoroughly enjoy my grandchildren when I’m around them. I’d like to expose them to all of the things that I had enjoyed and more for them, and hope that they understand the value of it and not take it for granted.

You also take care of your mom. Tell me a little bit about her.

My mother is the only parent of the Little Rock Nine left. She is 98 years old. And I’m the primary caretaker. I have two sisters. They do their share, but she looks to me because I’m the oldest. So that is a day-to-day event. I had the opportunity to enjoy my 80th birthday in Hawaii, and the whole family was there, including my mother. We were able to take her. So that in itself was one of those great moments in my life, because you never know how much longer we’ll all be around, and especially when you’re 98. So we have caregivers, and we are doing the best we can to honor her wishes, which is to remain home. And that’s what we are doing.

And my last question is, are there any things that you haven’t done that you still would like to do?

What I would really love to do is get back on the golf course, but I can’t do that. My knees are not the young knees that I had back in my 20s and 30s. I’d just like to travel more. Yes, that would be something that I would like to do. But what would really warm my heart, even more, is to see more and more women in positions of power, such as our Vice President of the United States, to see more women in Congress, to see more women involved in our state politics, to be able to teach their children and other children that they too can be in these positions. I would love to see more and more young people like the kids that spoke out against gun laws, those from Parkland High School in Florida. I’d vote for any one of those; the way they spoke out and spoke up, those sort of things warm my heart. They really do, to see that going on.

And I just spoke over here at East High School last year. And I’ll never forget this one particular year. It was the year of voting. I guess it was during the Obama presidency, and I suggested to those young people in that history class to go home and ask their parents to do one thing for them, and that was to register to vote and make sure they voted in the election that year. And I had seven hands to go up who said that they were already registered to vote. Now, that did me; they were old enough to register, and that was one of the first things that they had done. And that’s why the AP African-American Studies course is necessary. That helps them to develop those ideas of what they need to do to make their community a better community. Those seven kids who had already registered to vote, they understood that their vote counts, and I’d like to see more of that.