Mere seconds into the opening sequence of The Cheetah Girls, and I’ve already regressed into my eight-year-old self, cheesing at the four teens on my screen and imitating their honeyed melodies. I thought I’d forgotten it all — the buoyant songs, the rainbow velour, the toothbrushes that sang, the careful consideration of which girl I was — but then, I saw the overhead shot of Central Park set to the cheerful bop of “Together We Can.” Everything came back to me, all the moments and memories rushing forward like a New York City subway train emerging from the darkness.

Such is the pleasure of rewatching The Cheetah Girls, which premiered 20 years ago today. Among the many Disney Channel programs that shaped my 2000s childhood, The Cheetah Girls stands out for many reasons. The biggest one is that the film made me believe in the magic of Black girls dreaming undisturbed and undeterred. It inspired Black girls like me to dream with our whole hearts — and provided us the space to do so.

The Cheetah Girls, Disney Channel’s first ever musical movie, premiered on August 15, 2003 to 6.5 million viewers. Based on Deborah Gregory’s popular books of the same name, the film follows four teenage girls — Galleria (Raven-Symoné), Chanel (Adrienne Bailon), Aqua (Kiely Williams), and Dorinda (Sabrina Bryan) — as they pursue a major record deal. What enchanted me about the film growing up was the way it championed Black girls’ ambitions. Even though Chanel is Latino and Dorinda is white, I recognized myself in the ambition of Galleria (Symoné), who leads the quartet. Throughout the movie, Galleria talks about her hopes for The Cheetah Girls. She even sleeps under skyscraper-painted bedroom walls that spell out the group’s name in neon letters.

Like the characters, I once dreamt of becoming a singer. However, my fear of rejection and ridicule hindered me. This shyness contrasted drastically with The Cheetah Girls’ confidence; they performed whenever, wherever. Even during emergencies, they huddled together and harmonized. I couldn’t entertain strangers on the street like Galleria and Chanel. Still, I belted out “The Party’s Just Begun” and other songs from the franchise in the bathroom mirror, thanks to my Cheetah Girls musical toothbrush. The movie and its sequels taught me that even when dreams don’t materialize as you want them to, they’re still worth nurturing. Seeing the characters’ dreams evolve and adapt proved that I could nurture my passion for music in other ways. I could croon in my bedroom, and that would be magic enough.

Without The Cheetah Girls, I wouldn’t have believed that my aspirations mattered. Before I discovered the franchise, I watched High School Musical, Hannah Montana, and other projects that elevated white teen and tween dreams. In the second grade, I recall watching The Lizzie McGuire Moviein a teacher’s classroom. My own teacher had to run an errand around school and left her class with a neighboring instructor. I remember staring blankly at the Promethean board-turned-movie screen as the stand-in teacher bobbed her blonde head to the music. “Hey now, hey now!” Lizzie McGuire chirped. “This is what dreams are made of!”

The Cheetah Girls was the first movie I saw that specifically glamorized Black and brown girls’ dreams. It declared that my goals were worthy of glittery outros, fairy-lit bedrooms, and cityscape backdrops.

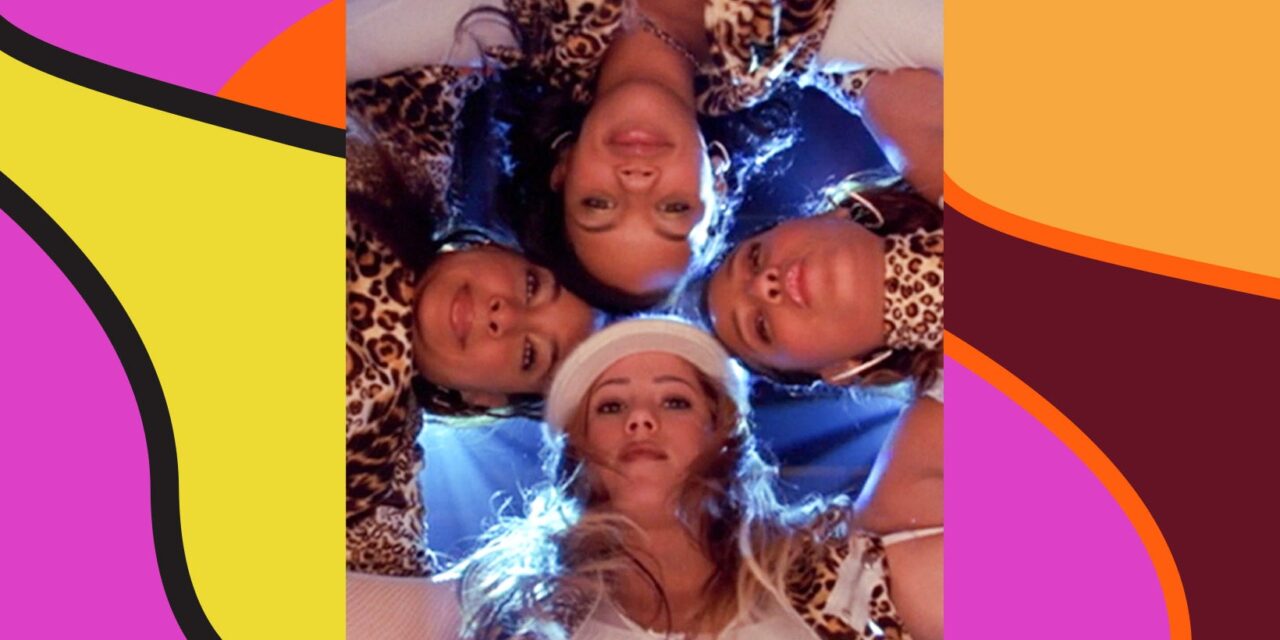

No scene encapsulated this sentiment more than when the group performs “Cinderella” — a song originally recorded by American girl group i5 in 2000 — for their school talent show audition. Once the song’s bridge arrives, the characters form a circle onstage with their backs turned inward. The stage dims. Then, streaks of speckled light bathe the girls in ocean blue. Floating their arms above their heads like sea-born seraphs, they lilt, “I can slay my own dragons. I can dream my own dreams. My knight in shining armor is me.” All the while, the camera pans them adoringly. I knew from that scene that I deserved everything: the movie magic, the fireworks, the mid-air leaps, the victory fists. I deserved it all. And, The Cheetah Girls assured me, I had the power to achieve it.

We can’t forget to honor the Black women that worked on The Cheetah Girls and thus created space for Black girls and their dreams. Deborah Gregory, who authored The Cheetah Girls books and co-produced the films, sought to write stories that would inspire girls of color. (In the books, all the characters are Black and mixed race.) She also took inspiration from the R&B group Destiny’s Child, whom she once interviewed for Essence magazine. Gregory went shopping with the group (yes, Beyoncé, too) at The Galleria mall in Houston. That connection inspired Raven-Symoné’s character as well as Kiely Williams’ Aqua, who is from Texas and coincidentally carries hot sauce in her bag, too.

Whitney Houston also co-executive produced The Cheetah Girls with Debra Martin Chase, the first Black woman producer to have a deal at a major studio. The film echoed themes from an earlier project that Houston and Martin Chase were involved in: the 1997 TV movie Cinderella, which starred Brandy as the titular princess. Beyond that, The Cheetah Girls cast Lynn Whitfield — one of Black Hollywood’s most recognized onscreen matriarchs — as Galleria’s mother. Whitfield and Symoné bonded on the sets of the first two movies and remain close, per their 2016 reunion on The View.

That Whitney Houston and Beyoncé are both attached to The Cheetah Girls in some way should be enough to cement the film’s legacy. But even the staunchest skeptic would fold under these statistics. The Cheetah Girls paved the way for other Disney Channel musical films like High School Musical, Camp Rock, and Teen Beach Movie. It was also the first DCOM with a soundtrack, which sold over two million copies in the U.S. alone. Additionally, the movie spawned two successful follow-ups set in Barcelona and India, respectively. And to top it off, The Cheetah Girls (sans Symoné) became an actual singing group; the real-life trio went on three nationwide tours and sold over 11 million records worldwide.

More precious than these accolades is the impact that The Cheetah Girls had on Black girls like me. The film encouraged our ambition instead of dissuading it. Even when Galleria grows arrogant about the group’s success, she simply learns her lesson and is told that her “big head” is full of “big dreams.” In this film as well as in its sequels, our dreams never become our undoing. Rather, dreams allow us to become our fullest and freest selves. Now that I’m older, I can recognize the full extent of the movie’s influence on my life. Its true legacy exists in the glittery inspirational quotes taped to my wall, in the goal journals piled on my desk, and in the essays I write affirming other Black girls and women. That’s where the real magic lies.