The press continued to build up the hype in the days before Wimbledon, incited by several intriguing elements. First on most everyone’s list of likely winners were the top seeds, defending champion [Lew] Hoad and Althea. The giant killer Hoad had recovered from arm and back injuries earlier in the season and was primed to become only the second man to win consecutive Wimbledon singles titles since the days of Don Budge. Reporters and players alike obsessed over the looming question of whether a victory would bring the mercurial Hoad one step closer to the $125,000 offer that professional promoter Jack Kramer had laid down a couple of months earlier.

Like Hoad, Althea was easily the favorite among bookies and pundits. Her most serious challenger was thought to be the thirty-four-year-old [Louise] Brough, four-time Wimbledon champion and the second seed. But age and anxiety had visibly undermined the older woman’s game, leaving Shirley Bloomer, Britain’s No. 1 player and the French Open women’s champion in 1957, the next most serious threat. There was also Angela Mortimer to consider, the “other Angela” who had beaten Althea several times in the beginning of 1956 and who was now emerging from a yearlong struggle with health issues. The bigger threat to both front-runners Althea and Hoad, as many saw it, was Althea and Hoad themselves, for both were inclined to self-sabotaging behavior when under stress. As the Daily Mail put it succinctly a few days before play began, “THE ONLY PEOPLE WHO WILL BEAT MISS GIBSON AND LEW HOAD AT WIMBLEDON ARE THEMSELVES. THEY ARE, WITHOUT DOUBT, THE BEST PLAYERS.”

Compounding the anticipation was the fact that, for the first time, Queen Elizabeth II was going to pay a visit to the All England Club and was expected to present the trophy to the women’s winner. That, coupled with the possibility that one of the new crop of British women players might at long last reverse the American domination of the women’s event that had prevailed since World War II, surely merited a whopping extra helping of strawberries and cream. Anything, it seemed, could happen. No doubt, the club’s thirty thousand seats would be jammed for the full two-week event given that over a half million dollars, the equivalent of $4.6 million today, in advance bookings had been made and lines were already beginning to form outside the gates a day before the tournament began.

Some in the Black press angled to get a read on Althea’s state of mind as she stood on the brink of possible world triumph, but few probed as deeply as Baltimore Afro-American columnist Sam Lacy, who had followed her for years. His lengthy story, titled “Has Althea Gibson Conquered Herself?,” which ran several days after play began, opened with the observation that “Althea Gibson is an enigma at the crossroads. A mystery to the experts in the field of sports, a puzzle to her closest friends, Althea this week seeks the answer to her own inexplicable personality.” Lacy mused over Althea’s trajectory in an effort to understand her erratic moods and lack of self-control on the court. Lacy, who apparently shared a certain discomfort with Althea’s less-than-feminine ways, believed that her issues stemmed from her chaotic childhood, and he suspected that her domination of boys’ sports as a child had ultimately worked against her. Later in life, he wrote, “the ‘tomboy’ finds herself victimized by complexes. Miss Gibson is no exception. Her frustrations have made of her an introvert. She has a way of going into her hard shell and refusing to come out of it.”

Both Lacy and Llewellyn, who was interviewed for the story, were insistent that race had played no part in Althea’s personality problems. “It is not that at all,” Lacy wrote. “Miss Gibson would be Miss Gibson if she were Nordic, Chinese or Afghanistani. It is her makeup to be moody, indifferent, sometimes arrogant.” Llewellyn heartily concurred, saying, “I know, and she has often said, everybody has been magnificent in their treatment of her.”

It is difficult to imagine, however, that the throbbing drumbeat of race that dominated the coverage of Althea’s Wimbledon play, particularly in the British tabloids, could not have had an impact or slashed at her sense of self. In those stories, she wasn’t “just another tennis player,” as she had explained herself to The New York Times on the eve of Wimbledon play the year before.

She wasn’t even just a “Negro tennis player,” as she had said she was not. She was a “Negress,” a “Negro,” the “coloured favorite,” and “the long-limbed ebony opponent”—all terms used to describe her in the British coverage of the opening days of the 1957 Championships. She was the “brown, lean Althea Gibson” with “supple brown muscles.” In fact, she wasn’t just a “colored” person, she was the dark-skinned representative of the entire colored race.

She was the girl on whose “dusky shoulders” an entire people’s prestige balanced. “Hers is no solitary battle but one which, successfully ended, must bring pride and perhaps hope to millions of under-privileged oppressed folk who share her colour.” She was “the Negro girl from Harlem, fighting with missionary zeal for the honor of the coloured peoples.” In a story headlined “Althea Beats Her Bogy—and Fans,” Clifford Webb of the Daily Herald summed up the formidable elements confronting Althea as she strode on to Centre Court for her first match this way: “Imagine you’re a coloured girl fighting for a place in sports history. . . . Your first match in the toughest two weeks of your life is about to begin . . . and 14,000 fans crowded in tiers around you are urging on your underdog opponent.”

Angela Buxton was equally blunt in a Daily Sketch column headlined “Althea Can Beat the Colour Bar.” In the piece, she catalogued the many racial slights Althea had endured over the years that she, Buxton, believed had left a racial chip on Althea’s shoulder, “which has always seemed to stand in her way.” While Althea might not run into any direct colour bar trouble at the All England Club this time round, Buxton assured her that “the feeling will be there nevertheless, just as it always has been.” Nonetheless, she urged her friend to stare it down and keep on fighting, concluding her column in all capital letters, “GO TO IT, GIRL! KNOCK THAT ‘BROWN’ CHIP OFF YOUR SHOULDER. YOU CAN DO IT THIS TIME!”

Buxton was without a doubt a genuine friend of Althea’s, one who perhaps wished the best outcome for her more fervently than anyone in the Wimbledon stadium. And yet, her column borders on the naïve. To reduce a lifetime of racial offense and discrimination such as that which Althea had experienced, never mind the weighty legacy of enslavement that also bore on her psyche, to a little brown chip on the shoulder approached the level of insult. The notion that Althea could simply brush away that annoying chip, could blithely toss a lifetime of injury into the rarefied Wimbledon air, was a failure of understanding. As Althea prepared to make a stand on Centre Court before the eyes of the world, it seems likely that she simply tossed her friend’s glib words on the pile of racial commentary mounting in the press.

Nor did the British crowd make it any easier. No sooner did an unsmiling Althea drive a ball into the net in the first game of her first match than many among the thousands packed into the stands erupt into cheers, just as Clifford Webb had predicted. They did not want the colored girl to win, as some saw it. Whether it was because of the tone of her skin, or the crowd’s nationalistic partisanship for her European opponent, Hungarian Suzy Körmöczy, or something else, it was to become the subject of much debate in the days and weeks to follow.

British pundits by and large attributed the jeering and eruption of applause prompted by some of Althea’s errors to a long-standing British sporting tradition of backing the underdog or simply enthusiasm for players close to their hearts. In a story headlined “Centre Court Bias Upsets Americans,” Daily Express veteran reporter Frank Rostron conceded that the crowd had reached “the unpardonable stage” in applauding errors by Althea, whom he described as “Harlem’s globe-trotting invader.” All that clapping was simply support for underdog Körmöczy, he continued, and was “nothing personal,” certainly nothing racist.

“While chiding the ignoramuses, who kept applauding Miss Gibson’s misses, I hasten to assure Althea’s countrymen that this was just the old story of the British crowd cheering the underdog,” Rostron wrote.

Some Americans disagreed. At the end of the tournament, the Pittsburgh Courier chalked up the two weeks of jeering and catcalls that Althea had endured at Wimbledon to “British color prejudice . . . there seemed to be thousands who did not want a colored girl to win.” The paper ran an unflattering cartoon of Althea that had appeared in a British newspaper; it showed a thick-lipped Althea clasping the hand of a white player at the net. Her seemingly southern-tinged words in the overhead bubble read, “Do I shake hands with the 17,000 spectators? Ah sure was playin’ against all of them too.” The overhead caption summed it up: “IT’S ALTHEA v THE REST.”

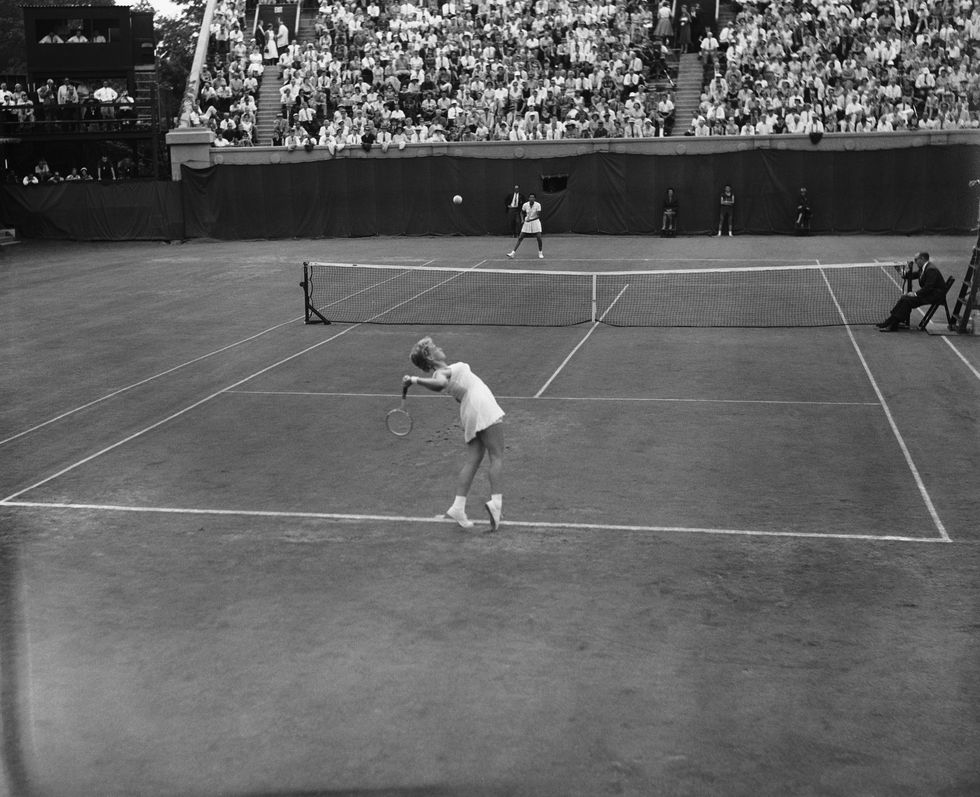

Even without the voluble crowd, it was a difficult start for Althea, who had scored a bye in the first round. Beset by nerves and seemingly flustered by Körmöczy’s persistent retrieval of some of her hardest-angled shots, Althea struggled mightily to best her petite opponent. Time and again, as warm rain began to descend on the grass court, her searing forehands missed their mark and soared over the baseline. In the end, Althea pulled it off and won 6–4, 6–4, but it was the hardest match she played in the tournament. In the men’s play the previous day, meanwhile, the big news was that the Ham Richardson, Althea’s amiable partner from her State Department tour and America’s No. 1 male player, was routed by Chilean player Luis Ayala in less than one hour. Hoad, meanwhile, had beaten his French opponent with ease and appeared to be well over his injuries.

With the temperature rising steadily in the ivy-draped tennis center, dubbed the “ivied oven” by one paper, Althea cruised through her next three matches in the coming days, as both her confidence and her standing among the bookies mounted. By the tournament’s midpoint, the only real surprise in what was turning out to be a fairly mediocre display of women’s tennis was the stunning performance by Britain’s teenage Truman, who had beaten Shirley Bloomer in a shocking fourth-round upset. Truman, whose rocketing forehand drive was already being compared to that of Maureen Connolly, scored another impressive victory in the quarterfinal against American Betty Rosenquest Pratt, America’s No. 5 female player, as the crowd leapt to its feet and roared in approval for several minutes. As the round-faced girl mopped her face wearily with a small blue towel, few cheered more excitedly than Truman’s parents and four of her five siblings, who were packed into a row together. Having made it to the semifinals, the freckle-faced schoolgirl confronted none other than the formidable No. 1 seed, the all-around favorite, Althea Gibson.

“I’m looking forward to it,” a smiling Truman told reporters. “What have I got to lose?”

On the day of the match, reporters flocked to Centre Court, while untold thousands of British women turned on the telly with their afternoon tea in the hope that the nation’s tennis sweetheart might reclaim the national championship title at long last. Utterly unfazed, Althea declared coolly before their encounter, “I’ll gobble her up.” Ears pricked up at the comment. When Truman walked onto the court that afternoon, a tennis ball rolled slowly in front of her. Bending down to pick it up, she found a newspaper headline of Althea’s prediction taped to the ball—an attempt at a joke from a friend, of sorts, who was sitting in the stands.

Althea, indeed, devoured Truman whole. As thousands looked on, she sent her young opponent flailing around the court from the first point pretty much to the last and never let up. It all came to an end in less than forty minutes at 6–1, 6–1, a score that told the story of the match. “It Was Murder on the Centre Court,” as the Daily Telegraph summed it up. Althea was in complete control from the first shot. Patiently, she waited for Truman to come to the net before unleashing a series of kill shots. As the Times put it, Althea was, “weaving her web around her gasping opponent like a spider. . . . She seemed to be everywhere at once, gliding about silently, effortlessly, and seemingly at half pace, which is always the illusion given by a fine player. Miss Gibson is that.” Although Truman lunged and ran as best she could, she could neither pass Althea at the net nor return her succession of deadly kick serves. The second set was slightly closer, as Althea double-faulted twice and Truman steadied herself, but Althea swiftly closed out the match with a serve that Truman belted far off the court. Smiling, Althea slowly approached the net and amiably reached out a hand to her young opponent.

“She said, ‘You’ll get here one day,’ ” Truman recalled in an interview. “You know, she was always very nice to me.”

Althea’s win delivered her to the door of the Wimbledon women’s finals, across from opponent Darlene Hard. Here were two American women, as far apart in background and appearance as they could possibly be, one a moody dark-haired easterner, the other a squat ponytailed college girl from the West Coast nearly a decade younger. They were also friends. Hard, who had learned tennis on the public courts of Southern California from her mother, was as amiable as she was approachable, and she clearly relished playing with Althea. Over the past year, Althea and the “chunky California waitress,” as Hard was routinely referred to in the tabloids, had become a formidable doubles team, winning four tournaments, most recently at Queen’s Club weeks before. At Wimbledon, they were the first seed of the women’s doubles and had made their way with relative ease to the finals, where they faced Mary Hawton and Thelma Long of Australia.

The ebullient Hard was known for playing somewhat erratic tennis, regarded by some as a reflection of her carefree personality. On her good days, she was as forceful as any woman on the court, with her flat serve and deliberate backhand, and easily outran her competitors. On her off days, she chronically double-faulted, and her play veered from wild shots to unreturnable winners. Over the past year, Althea had beaten her four times, most recently in a fierce three-set battle at Beckenham during which Hard double-faulted six times and Althea did so at set point. Hard, however, had been playing extraordinarily well at Wimbledon so far, exhibiting a more mature game of measured strategy and control. Earlier in the day, she had disposed of American Dorothy Knode in a decisive, if unexciting, semifinal contest that lasted only forty-three minutes. She had even sent aging queen Brough packing in the quarterfinals, perhaps the biggest win of Hard’s career to date. The crowd, moved by the significance of Brough’s defeat, gave her a heartfelt ovation as she walked despondently off the court.

And then it was time for the finish. On the second-to-last day of the tournament, Lew Hoad had retained his men’s singles title in a dazzling performance, defeating his fellow Australian Ashley Cooper in a mere fifty-six minutes. “Hurricane” Hoad’s performance, as The New York Times described it, “must rank as one of the fiercest hitting rampages in tennis history.” Afterward, Hoad repeated his plan to remain an amateur until the end of the year. On the last day, all the remaining rivalries that had played out over the past two weeks would come to an end, including the women’s singles final and the doubles and mixed doubles finals.

Althea was more than ready for what lay ahead. After a boisterous press conference on her defeat of Truman, and a quick shower, she headed back to the city in her small rented Austin. So confident was Althea in her ability to win the championships in those final days that she had bought herself a stunning floral-print strapless gown with a festive bow tucked under the bustline, which Angela had helped her pick out at, of course, Lillywhites, to wear at the celebratory ball.

Althea had also spent days penning a three-and-a-half-page victory speech in green ink on onionskin paper for the event. That evening, she laid out her clothes for the following day: a brand-new pair of creamy-white pleated tennis shorts made for her by designer Teddy Tinling and a crisp white Fred Perry shirt. Her tennis shoes, freshly cleaned by a clubhouse assistant, were ready to go. At dinnertime, she headed out with a pair of friends from the ATA circuit to her favorite London restaurant, an elegant French bistro called Le Couple, where she feasted on filet mignon broiled in butter and a glass of sherry. Althea had come a long way from the days when she toured the American South in the backseat of Dr. Johnson’s packed green Buick and had a gun stuck in her face at a gas station because of the color of her skin.

The day of the finals dawned blistering hot, with the mercury headed north of ninety degrees by late morning. Warming up on a remote court, Althea happened to notice Queen Elizabeth having lunch on the clubhouse porch, which reminded her to take with her the instructions she had been given for the curtsy protocol before the Royal Box. Shortly after 1 p.m., Althea and Hard headed into the ivy-covered inferno as a crowd of seventeen thousand spectators fanning themselves with their programs seemed to hold its collective breath in the blistering heat. Althea and Hard, sporting a Tinling dress with blue trim, both clasped bouquets of red, white, and blue flowers, representing their American citizenship, as they walked slowly onto the court and paused to curtsy before the Queen in the Royal Box.

It was not a good final, as the pundits would later declare. So sluggish was the match that one reporter would call it “almost pathetic,” while a World Tennis writer dubbed it “the worst women’s final ever remembered.” In fact, it was painfully slow, with more games won as a result of player error than any brilliant shots. Not a single rally in the entire match lasted longer than five strokes. Neither of the players was in top form. While Althea was in calm control throughout, she was clearly playing with uncharacteristic caution. Meanwhile, Hard, limp from the heat, her face etched with anxiety, seemed unmoored from the start, tossing her ribboned blond ponytail nervously as she was repeatedly overwhelmed by her opponent’s high-kicking second serves. In the first four games, she managed to win only four points. On the brink of taking the seventh game at love–40, with two games now in her pocket and a pair of advantage points in her favor, Hard flubbed her return. And with that failure, wrote Stanley Doust, former Australian Wimbledon finalist and a longtime tennis correspondent, “Miss Hard was never again in the picture.”

Althea took the first set 6–3 in under twenty-five minutes. In the second set, she picked up the pace, while Hard appeared to wilt completely after losing her first service game, her usual effervescence squashed. Althea continued to rush the net while maintaining her laser-like focus, pausing only to glare with harnessed irritation at the perspiring linesman making repeated calls of foot faults. Nor did she allow the crowd’s annoying habit of clapping at her mistakes, just as they had done in some of both her and Lew Hoad’s earlier matches, to distract her. Hard struggled fitfully onward, at times dropping her head in her hands in despair. In a few memorable instances, she even paused to applaud Althea’s shots ripping by her.

Armed with a new set of balls in the final game, Althea delivered a series of searing serves and triumphantly took the set without surrendering a single point. The match was over at 6–3, 6–2 in fifty minutes. With that final shot, not only was one woman’s epic undertaking of more than fifteen years accomplished, but a page in the history of the African American struggle for parity had irrevocably been turned.

A beaming Althea rushed up to the net and threw her arm around Hard as the crowd erupted in exuberant applause that rang through the tennis complex. The two drenched players were escorted to the trophy table near the umpire’s chair, while a thick green carpet was unfurled for Queen Elizabeth and three of her attendants. One by one, the players again curtsied for the monarch, who was clad demurely in a rose and white silk dress, a beribboned pink hat, and white gloves, before Althea approached her. As the crowd looked on, seemingly more riveted by the ceremony than it had been by the sluggish match, the Queen presented Althea with the Venus Rosewater Dish, the silver salver engraved with the names of all the previous Wimbledon champions.

“At last, at last,” Althea exclaimed.

“My congratulations,” the Queen said to her. “It must have been terribly hot out there.”

“Yes, Your Majesty,” said Althea, “but I hope it wasn’t as hot in your box. At least, I was able to stir up a breeze.”

Althea, the first Wimbledon winner to be presented with a trophy by the Queen, teared up as she curtsied, and then stepped back so that Hard could come forward to accept her trophy as the camera flashes erupted. The press followed up with an explosion of superlatives and a succession of more photographs back in the club pressroom.

“Althea Gibson fulfilled her destiny at Wimbledon today and became the first member of her race to rule the world of tennis,” declared The New York Times. The Baltimore Afro-American headline announced simply, “Althea Is Crowned.” The Evening News put it slightly differently, saying, “QUEEN SEES COLOURED GIRL WIN WIMBLEDON CROWN.” And then there was the Sunday Pictorial headline: “ALTHEA—BUT SO DULL!”

Some among the Black press put it in even more cosmic terms. Her win, thundered Sam Lacy, “is the greatest triumph a colored athlete has accomplished in my time. . . . Althea, on Saturday, beat the world at tennis.” Others wasted no time in raising the question of whether Althea would use her status to help other Black people, just as she had been helped by so many. As P. L. Prattis of the Pittsburgh Courier wrote, “Faith in Althea has paid off. But what now—now that the door is open? Jackie Robinson walked through the doors of organized baseball due to the efforts of others, and kept the doors open for scores of others. What will Queen Althea do?” To Gordon B. Hancock, a prominent professor and columnist for the Norfolk Journal and Guide, writing for the Associated Negro Press, Althea’s triumph symbolized the journey of the entire race. “We might have been foiled in Reconstruction days, and we may be foiled in the Year of Our Lord 1957,” he wrote, “but if we keep on coming back for another round, one day the Negro race will be worthy of the heart and stamina of Althea Gibson. Long live Althea Gibson, Negro!”

One can only imagine how that ringing statement struck Althea, she who had resoundingly declared on the eve of her Wimbledon appearance the previous year that the one thing she was not was a Negro tennis player, but simply a tennis player just like anyone else. Now she was being trumpeted as not only a Negro player, but a heroine forging the way for the entire Negro race.

The cymbals would grow ever louder before they subsided.

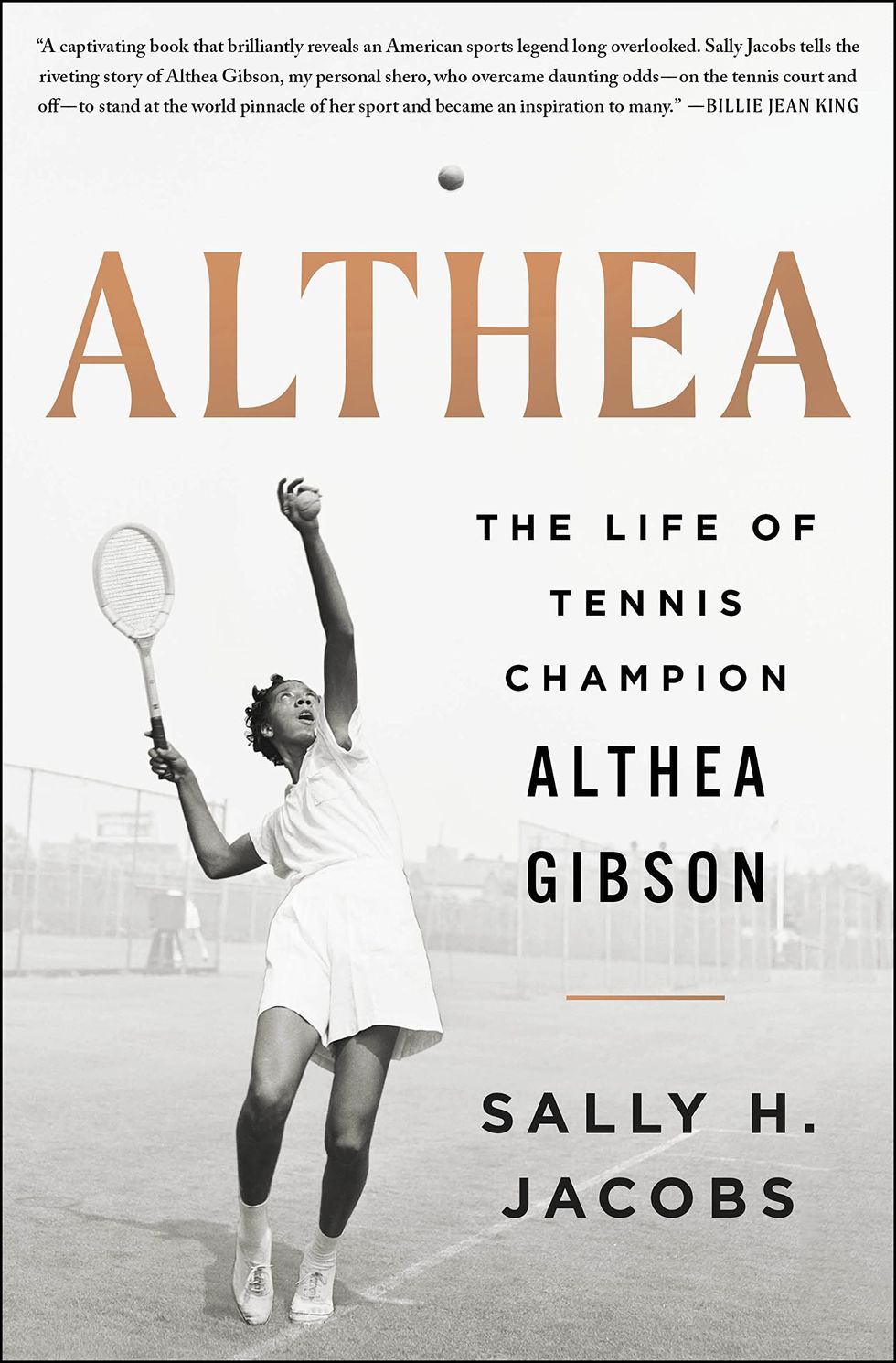

From ALTHEA: The Life of Tennis Champion Althea Gibson by Sally H. Jacobs. Copyright © 2023 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Writer

Sally H. Jacobs is a former reporter for the Boston Globe, and winner of both the coveted George Polk Award and the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Reporting with the Globe newsroom. She is the author of The Other Barack, a biography of Barack Obama’s father.