In this episode of the new Smithsonian magazine podcast, “There’s More to That,” journalist Emily Tamkin, who wrote a cultural history of Barbie for our June 2023 issue, turns to Ken, Barbie’s perennial plus-one. With Ken’s existential crisis getting a surprising amount of screen time in Greta Gerwig’s runaway hit film Barbie, we look at various attempts to make Ken more than just a plastic hairstyle over the decades. Tamkin, who has written extensively about Jewish identity in America, also considers what Barbie creator Ruth Handler’s famous offspring might tell us about the American dream.

A transcript of the episode is below.

Chris Klimek, host: When writer Emily Tamkin was little, she created a whole imagined life for her Barbie and Ken dolls.

Emily Tamkin, Smithsonian magazine contributor: We sent these Barbies to college. They had different careers.

They took extended family trips together. They had the trailer that we would load the Barbies up into for road trips.

Klimek: Barbie was always the star of the show. And in all her imaginary plotlines, Emily can only remember her Ken doll playing one featured part.

Tamkin: In the ’90s, when a sexual harassment case came before the Supreme Court, I somehow as like a 9-year-old found out about this and had my Barbie take her boyfriend Ken to court for sexual harassment.

Klimek: What was the outcome of the case?

Tamkin: Yeah, of course Barbie won.

Klimek: Emily recently wrote about the history of the Barbie doll for Smithsonian magazine. She also said that in her own play, the character of Ken took something of a backseat in Barbie’s pink convertible.

Tamkin: I think that my Kens sort of fell into the traditional Ken paradigm where, you know, he was always in relation to Barbie. I can’t remember ever having a Barbie game where the plot centered around the Ken.

So even if he was the father or the boyfriend or the husband or the professor or the teacher, whatever he was, it wasn’t like, “Today we’re going to play this really great game and it’s all going to be about Ken”–ever. Sorry, sorry to Ken.

Klimek: Yeah, the poor guy.

If Barbie was presented to girls as an aspirational ideal of womanhood, what does that say about Ken? Greta Gerwig’s new film Barbie opens in a pink plastic utopia called Barbieland. But everything changes when Barbie–played by Margot Robbie–has an existential crisis. And Ken, played by Ryan Gosling, learns about something called “the patriarchy.”

In an interview with Jimmy Fallon last summer, Ryan Gosling talked about what it was like for him when the world found out he was playing Ken.

Clip from “The Tonight Show”:

Gosling: I was, uh, surprised how, you know, some people were kind of clutching their pearls about my Ken as though they ever thought about Ken for a second. He’s an accessory—and not even one of the cool ones.

Klimek: From Smithsonian magazine and PRX Productions, welcome to “There’s More to That,” a podcast where journalists around the world bring you history, science and culture through the lens of Smithsonian magazine. Today, we turn our attention to the Ken doll … Someone should do it!

I’m Chris Klimek. Here we go.

Klimek: We spoke with Emily Tamkin just before the Barbie movie hit theaters and just after her article came out. We had both just seen the trailer for the new movie.

Clip from Barbie trailer:

Robbie (as Barbie): What’s going on? Why are these men looking at me?

Gosling (as Ken): Yeah. They’re also staring at me.

Klimek: I wrote a companion piece to Emily’s article about different Ken dolls through the years, and I wanted to compare notes about this simultaneously iconic and overlooked doll.

Klimek: There’s a big reaction to the first appearance of Ken, Ryan Gosling’s Ken, in the trailers for the Barbie movie. Do you remember reacting to that in any particular way?

Tamkin: With euphoria, with obsession? No, I think it’s great. I think they’re really playing on the sort of, not tension, but the twist of the trope, which is that very often we have superhero movies or we have, whatever the story is, and it’s all about the guy.

And he has this girlfriend who’s not a really fully fleshed-out character, and who really only exists or matters insofar as she has this boyfriend. And this is exactly the reverse, right? Even in the promo for this movie, it’s, “She’s everything. He’s just Ken,” is the tagline that they’re going for.

And I think they gave an interview, the various people involved in this movie, where they basically said, like, “He only exists when she looks at him.” You know what I mean? Like, Ken is only relevant insofar as he has Barbie’s attention, or insofar as he’s connected to her. So I think that they’re really playing up that dynamic.

Klimek: Yeah, I know Gosling on the promotional tour for this has already described Ken’s occupation as “beach.” But, let’s back up, and let’s start with Barbie before we get into her perennial plus-one. She’s been a doctor, she’s been an astronaut, she has run for president.

Tamkin: Every year since ’92.

Klimek: Oh, wow.

Tamkin: Or every election year, presidential election year, since ’92.

Yeah, I mean, it’s only appropriate that our conversation about Ken should start with Barbie because, as we say, he only makes sense relative to her. And even the name—you know, Barbie is invented in the 1950s.

And basically Ruth Handler, she looked at her daughter playing with paper dolls and imagining these wonderful stories for what these paper dolls might be.

And it just seemed like the form of the paper doll was too flat to really carry the hopes and dreams and imaginings of her daughter. Plus, she had seen this novelty doll while traveling in Europe that had a more buxom shape and thought, “What if I put these two ideas together?”

And thus Barbie was born, and Barbie takes the name from Ruth’s daughter, Barbara. Two years later, when Barbie gets a boyfriend, it’s just named after her son. So it’s like, “We’ll give her a boyfriend, that kid that I also have.” No, so they’re named after her children, Barbie and Ken.

But when Ruth Handler first came out with Barbie, one of the things that she heard from others in the toy industry was like, “Nobody’s going to want to buy this curvy, quite adult-looking doll.”

We can get into the feminism of Barbie if you want. But her point has always been that Barbie is meant to suggest that girls can be whoever they want to be.

Whatever you imagine, whatever outfit you can dream up putting on Barbie, you can be it. So in the piece, I mentioned that before an American woman ever went to space, there was an astronaut Barbie. As you say, Barbie’s been a doctor. Barbie’s run for president. There’s also been a Barbie doll who has said that math is hard.

Klimek: I learned from your story that “math is hard” Barbie was 1992, not, you know, 1961.

Tamkin: Right. And there have been moments where Barbie’s been in a more regressive space, like in her earlier years she had a “How to Diet” book. And there have been moments where Barbie’s been more progressive, when they’ve really tried to offer different body types for Barbie and sell Barbie in different races, or have Barbie have these amazing careers.

So she’s gone back and forth, and Ken has kind of been along for that ride.

Klimek: Do we know anything about what’s on Ken’s resume?

Tamkin: Yeah, I mean, Ken’s had some careers …

Klimek: Beach. I mean, you know …

Tamkin: He’s had beach.

No, like, you can buy different Kens, but it’s also the trap of Barbie. Is that, on the one hand, she’s a figure who receives ire from feminists, right? Or from just people, like, what is this? She’s white, she’s blonde.

She has this impossible figure and she’s very beautiful, and you can dress her up in different ways. But at the same time, Barbie’s always breaking that mold, because the clothes that they assigned to her, as we talked about, are of any profession. And once you give a girl or boy a Barbie doll, they can play with it and have it, as Ruth Handler said, be anything. And do anything.

And as one person I spoke to for the piece said to me, often what the children imagine is far beyond what you could read on the side of the box, which I think is true. But there’s a gender dynamic there. This very stereotypically feminine-looking doll, breaking the mold of what people think women and girls can do.

I don’t know that there’s the same dynamic going on with Ken. Because, and I don’t mean this disrespectfully, but like, what in this country have white men not been raised to think they can do? So it’s not like, “Wow, candidate Ken.” Doesn’t have the same sort of excitement as presidential candidate Barbie.

Klimek: He did it!

Tamkin: Yeah, yeah … again!

Klimek: Let’s talk about the appearance of Ken. Can we first say what we knew about Barbie’s identity prior to the introduction of Ken? And then tell us about how and when Ken was introduced.

Tamkin: Yeah, I mean, it wasn’t just Ken. They built out the Barbie fam. So there’s her friend Midge, there’s her little sister Skipper, and then Ken. It basically was like, “Well, Barbie needs a boyfriend.”

But, it was quite soon after. I think Ken’s from ’61 and Barbie’s from 1959. So really, right on the heels of Barbie we do get Ken.

Klimek: She’s had two years of freedom, yes …

Tamkin: Right, being an independent doll. … And then I think at some point, Mattel announced, “Barbie and Ken are breaking up,” or after 50 years, “Oh no, they’re back together.”

But I don’t know that the official company narrative of Barbie and Ken’s relationship has dictated how most people have thought of it.

You know, I will cop to this on this podcast. I had Barbies and Kens growing up, and the relationship between the individual Barbies and Kens that my sister and I played with—Mattel was not telling us what those were. We had a whole extended family, you know. That was us. Mattel didn’t tell us to do that.

Klimek: Yeah. I mean, are you willing to share a little more about that, the lore that you and your sister invented?

Tamkin: Yeah, we called them the Mayer family. And it was like, I had one nuclear family. She had one nuclear family.

And so I guess this is what I’m saying, is it didn’t matter to us if Mattel said, “Oh, Barbie and Ken are together or not” or like, “Oh, Ken’s from Wisconsin.” Cause my Ken could have been from New Jersey and married a woman from Michigan. Actually, I did have one Barbie go to the University of Michigan.

That was all invented by us. So Ken stans, don’t worry. He’s been given a much richer story than has been afforded to him by his company, by the families who have played with him across the United States and the world.

Klimek: Was Michigan her first choice or safety school?

Tamkin: No, but University of Michigan’s a great school. This was this individual Barbie’s first choice. I think I had that Barbie become a teacher.

Klimek: Emily has spent a lot of time thinking about the racial politics of Barbie. She writes about this in her book Bad Jews: A History of American Jewish Politics and Identities. It turns out that even when the Barbie universe expanded to other body types and skin tones, it didn’t necessarily change the minds of the consumer. Emily spoke with anthropologist Elizabeth Chin about this.

Tamkin: Elizabeth Chin said, for her, if white, blonde Barbie is selling more than the Asian-looking Barbie or the Black Barbie—not to say that Mattel has not reinforced some of these beauty standards—but it’s consumers who are making the choices about which of those dolls they want to buy because of their own internalized prejudice, and their own sense of what is and what is not beautiful. It’s a bigger problem than just the company.

Klimek: This is a thing that you write about in a really nuanced way in your piece about how the Handlers were a Jewish family and how even for the creators of Barbie the aesthetic of Barbie was kind of a fraught subject.

Tamkin: Yeah. And I’m not trying to say that Ruth Handler was consciously going through all of this, but I do think it’s important that it comes out of this certain point in American history.

The 1950s and 1960s and generally the postwar period in the United States, you see American Jewish families, many of them, moving out to the suburbs and having a sense of security, socioeconomic security, but also just in terms of, like, we’re Americans, we’re securely here now in a way that they didn’t have in the prewar period. And you also see a lot of ambivalence about that, because there was the sense that if you’re not impoverished, if you’re not struggling, if you’re not being persecuted, like, is that really authentically being Jewish?

And meanwhile, while American Jews are grappling with their own ambivalence about what it means to now be suburban Americans, here comes Ruth Handler inventing the Barbie Dreamhouse, inventing this very stereotypical-looking, all-American young man, young woman doll …

And literally the house with the white picket fence and selling it, commodifying it as the dream.

I should also say that the postwar period is one of great ambivalence of gender roles for American Jews. This is the period where the development of the idea of the Jewish American Princess comes up, of the American Jewish man as being like nerdy and whiny compared to the strong Israeli.

All of this, at the same time, you have Barbie and Ken, who were like, classic. The all-American man and the all-American woman. At the same time that the American Jews are sort of like, “Well, what does it mean to be an American Jewish man or an American Jewish woman?”

Klimek: Yeah. What this makes me think about is, you know, someone who grew up playing with superheroes and reading comic books and stuff. When you and your sister were playing with your Barbies and then subsequently as an adult, I read about how all of the superheroes who are, you know, dominant in the culture now, all created by Jewish writers and artists.

Most famously, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster creating Superman in the ’30s. And they create this invulnerable, you know, fantasy man, kind of in the same way that Barbie is this impossible physical ideal a generation later.

Tamkin: Totally. Yes, totally. I think that’s a great comparison.

Klimek: So how have Barbies changed and adapted with the times? When do we start to see Barbies with different skin tones, hairstyles, things like that?

Tamkin: Yeah, well in 1968, Barbie gets a Black friend, and this coincides with the civil rights movement. And it’s only later that a Black Barbie, like proper, is put on the shelves. And they’ve gone back and forward through the years there, there have been, um, pushes at various points to be like, “Look at our diverse range of dolls.”

Several years ago, almost a decade ago now I think, there was a big push to put out Barbie dolls of different body shapes, and breaking with this idea that “Oh, she has this perfect unattainable figure.” I think Barbie has been used as a stand-in. I was at a women’s rights protest, this is several decades ago, and there are signs that are like, “I’m not your Barbie doll.”

You know, as a sign of “You can’t put this hyper-feminine pressure onto me as a woman.” Which, again, I do understand even if Mattel would say, “Well, you could be anything,” that’s the whole point.

And by the way, I think we could say the same for Ken’s body, which is not realistic for most men.

Klimek: Yeah.

A lot of Barbie’s different careers seem to reflect an attempt to keep current with the times on the part of Mattel. In the 1980s, when movies like 9 to 5 are coming out and foregrounding this idea of women acquiring more influence in white-collar environments, we get Barbie in a pink kind of power suit.

Tamkin: It’s Day to Night Barbie, so she has a pink suit and she can wear it to the office and then she can wear it out on the town.

Klimek: OK.

Tamkin: It’s exactly as you’re saying. It’s the ’80s. It’s this moment of, like, the businesswoman, like, working.

Klimek: So is there a similar attempt to make Ken multifaceted to reflect his professions?

Tamkin: Yeah, look, you can buy Kens in different careers and who have done fun, different things.

I think moving forward, what I don’t know that we’ve seen enough of is: Barbie and Ken come from a time in which we thought of gender as pretty binary. It’s a very heteronormative project. You have Girl Barbie and you have Boy Ken, and the assumption is that they’re going to date. And so I don’t know that we’ve seen Mattel play with Pride, you know, as much as one might think, given where we are culturally in this moment, or as people increasingly publicly identify as nonbinary or as gender fluid.

To have a progressive Ken in the same way that we’ve had a progressive Barbie would look different. Right? It wouldn’t be like, you can be a doctor. It would be like, you can be a teacher, which is a very feminized profession. You can be a stay-at-home dad. You can be a caretaker.

Because Barbie and Ken exist in the world, and the world puts different pressures on men and on women. Some are the same, but many are different. What looks progressive for the female-presenting toy is going to be different than what looks progressive for the Ken.

Clip from a 1960s Barbie commercial:

It all started at the dance. Barbie, the famous teenage fashion model doll by Mattel, felt that this was to be a special night. And then it happened. She met Ken! And somehow she …

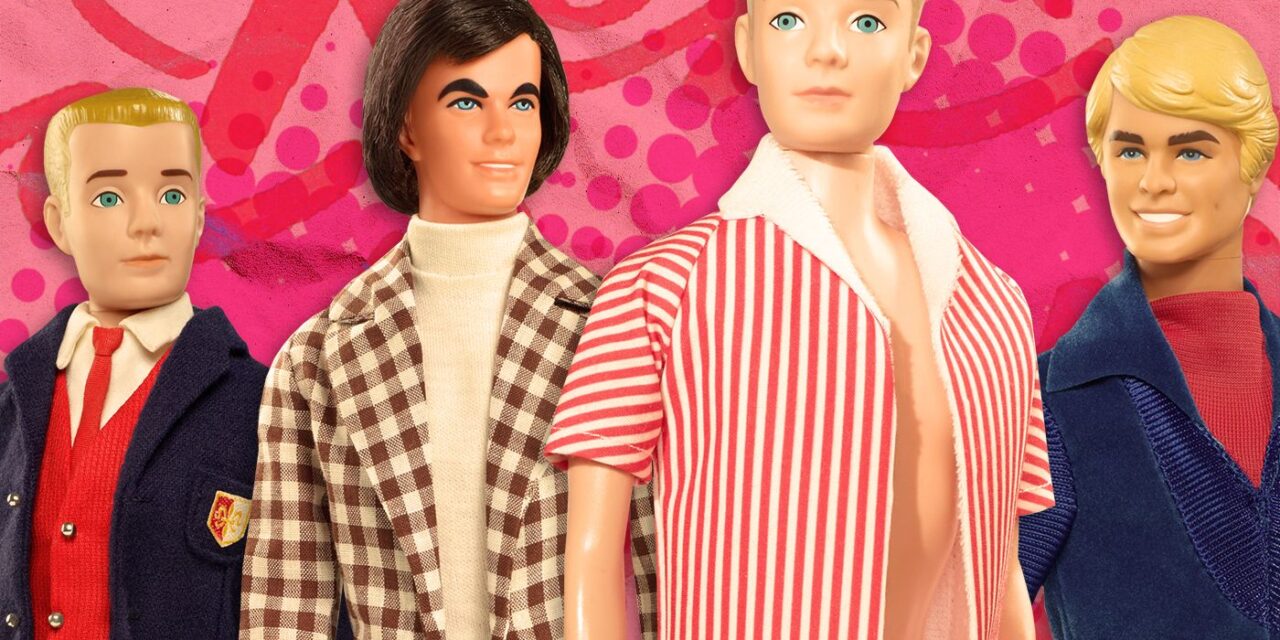

Klimek: To get a better understanding of where Ken has been, and where he might go in the future, Emily and I sat down together and watched some ads for different Ken dolls over the years. We started with Ken’s debut in 1961.

Clip from the 1960s Barbie commercial:

Now Ken and Barbie meet for lunch at school. Go to fraternity parties and just relax together. Think of the fun you’ll have taking Barbie and Ken on dates. Dressing each one just right. Get both Barbie and Ken, and see where the romance will lead. It could lead to this! And remember …

Tamkin: OK, what I want listeners to know is that having just watched that ad, Barbie looks great, and early Ken was looking kind of rough. The plastic hair and …

Klimek: Yeah.

Tamkin: So, Ken did great in asking Barbie out at that dance. We can hear both strains or threads of what we’ve been discussing in that ad. She’s a teen fashion model at a dance.

Klimek: Famous teen fashion model.

Tamkin: She’s a famous teen fashion model. They’re at a dance and they go for lunch.

If you look at the video, they’re dressed in this very 1950s, all-American, clean cut garb. They’re getting married; they end up at the aisle.

I think in part this is meant to sell different outfits, which was another part of Ruth Handler’s genius, really, was that you can buy one doll and then have all of these different outfits that you need to buy for her. You’ll need to buy Barbie’s park-walk outfit or Barbie’s bridal gown.

Klimek: I was thrilled to learn in my research about Superstar Ken. This is, uh, 1978. The box is trumpeting his handsome movie star face. And the fact that he is more poseable than ever, which turns out to mean that he can swivel his neck.

Tamkin: Love that. Love that for Superstar Ken …

Klimek: Yeah, if you wanna dance like John Travolta, you gotta be able to move your neck a little …

Tamkin: Right, exactly.

Klimek: Has a slightly more animated facial expression than prior Kens. He looks like he maybe knows more than he’s telling, and he’s got, like, I guess I would’ve called it a leisure suit.

But this blue, big lapel, you know, kind of bell bottom thing with the giant belt buckle, which was described in the box as a “celebrity jumpsuit.” Not a term that I had encountered before. But came with, like, a child size ring, I guess.

So that the kid buying the doll could wear the same ring that Ken had on.

Tamkin: Ken and Ken’s owner finally get some fashion attention as well.

Klimek: Let’s hear another piece of archival audio that gets into the increasing sophistication of the hair on these dolls.

Clip from a 1973 Barbie commercial:

Who are those great-looking dolls? It’s Quick Curl Barbie and Mod Hair Ken. Pretend they’re starring in a movie. Style Barbie’s quick-curl hair instantly with her curler or brush it into a flip and it stays. Put a mustache on Ken and make believe he’s the bad guy. Or sideburns and play he’s the hero. It’s fun pretending they’re movie stars, isn’t it? Quick Curl Barbie and Mod Hair Ken dolls with their own accessories each sold separately from Mattel.

Klimek: There’s some aspersions about men with facial hair there.

Tamkin: “Pretend he’s a villain.” Mustaches are really having a moment right now, too. I love at the beginning where they’re like, “Who are those great-looking dolls?” You know full well that they’re Barbie and Ken, Mattel ad. Don’t you even pretend. First of all, what amazing leaps and bounds we’ve made in doll hair technology by the ’70s that we have Quick Curl Barbie. But I think now, looking back—and maybe at the time, probably, for some at the time as well—this is very racialized.

Like, this is a certain kind of hair that is being held up as, “Look how wonderful this is.” And I honestly had this Totally Hair Barbie in 1992. I had the same thought where it’s like, “Oh, look how long the hair is.”

Regardless of all these other Barbies of professions and ethnicities that have been sold, Totally Hair Barbie is, I believe, still the best-selling. And also we should say that, so yes, in 1968 we have Barbie entering her civil rights moment. But a few years later, we have Quick Curl Barbie.

So I like, what I don’t want listeners of this program to walk away from is the idea that like, yes, in the ‘50s it was a little traditional, but then we’ve just been on a progressive sprint ever since. Like, absolutely not. I think Barbie and Ken’s relationship to feminism, femininity, careers versus whatever that was ebbs and flows.

Klimek: All right, so that was 1973. 1982 is when we get to Sunsational Malibu Ken. And there was a sort of blonde-haired, blue-eyed, version of this doll, and a Hispanic version. The Black Sunsational Malibu Ken had the rooted hair, had an Afro.

You know, it wasn’t just like a molded, plastic helmet glued onto his head. And then after the initial production run, apparently never reappears. Like, the Black Sunsational Malibu Ken is apparently much sought after for his rarity, but also the hair.

Tamkin: Mhm. I mean, we talk about like Barbies of different skin color, but hair is also racialized. And so I think it speaks well of Mattel that they put that attention to detail …

Granted, it took them like 25 years to do it.

Chris: Let’s look at an ad for Sport and Shave Ken from 1979.

Clip from advertisement:

I’ve got a shaving gear. Wet the play razor, and you can take off Ken’s beard and mustache. Then put it on again with this beard marker. Better fix your hair. OK! Nice beard, Ken. It’s Ken and Beauty Secrets Barbie. Sport and Shave Ken Doll with two play razors and a beard marker. Beauty Secrets Barbie Doll is sold separately. New from Mattel.

Tamkin: OK, so we should note that even in this ad where you’re making Ken shave, the ad shows two little girls playing with the Ken.

Klimek: Yeah, but they’re accompanied by their fathers, presumably. We see two adult men, kind of, yeah. Is there anything to …

Tamkin: Just looking on approvingly as their daughters shave their Ken doll’s faces, and then draw the beard on again …

Klimek: Yeah. Do you think it’s the expectation “Well, you know, certainly, these young women are going to have to know how to shave a man’s face …”

Tamkin: I don’t, I couldn’t. It’s also just like, someone at Mattel thinking like, “What do men do? They shave.” Like, what are some activities?

Klimek: Mostly … just that.

Tamkin: Activities that Ken should do? Yeah.

Klimek: OK. So then in 1996, we have Cool Shavin’ Kens. Multiple generations of shaveable Kens.

Clip from advertisement:

One very good day. Your Cool Shavin’ Ken gives Barbie a kiss. His beard tickles her chin. Time to shave, lather up. Shave his beard off. He looks so nice. He smells so good! ‘Cause he wears Old Spice. What a hunk! He feels so good! Barbie kisses him twice. Shave him again and again. Love that Cool Shavin’ Ken. Cool Shavin’ Ken doll’s beard disappears with warm water.

Tamkin: So I think there we have a much more ethnically ambiguous Ken.

Klimek: I noticed that too. Yeah, olive-skinned. Boy, that poor man is just not going to have any skin left on his face.

So that’s 1996, which is a few years after this, the saga of Earring Magic Ken.

Mattel’s official line was that this was an attempt to modernize Ken based on the results of a survey that was conducted among their customers.

But the Ken that was issued had, most famously, the earring, but, you know, a leather vest, a mesh shirt … dramatic transformation in wardrobe from prior Kens.

What do you think Mattel might have been responding to circa 1993 to give Ken such a dramatically different new look?

Tamkin: I don’t know what the survey said, but I think they were trying to acknowledge that the polo-wearing Ken that we saw in 1961 when Barbie first got her boyfriend, that was not how people were dressing anymore. Or just to acknowledge that there’s different sorts of ways that people dress.

You know, the ’90s were such an interesting time politically in the United States that I think perhaps there was some backlash that they didn’t expect. Or that it was read as being more sexualized than they intended. But I think Mattel’s always attempted to stay relevant, you know, and have Barbie and Ken stay relevant and stay a part of the conversation, and that’s reflected in how they dress, even if their careers haven’t changed and they’re still shaving.

I will be very interested to see sales from the Barbie movie. Because what I think is really funny about the way they’re doing this is that Ryan Gosling is imbuing his Ken with such personality. Even as he’s saying, ‘Nobody ever thinks about Ken,” clearly he’s made a very memorable Ken.

They’re making a line of toys that will go with the movie. And I’m curious to see how the Ken dolls do, you know? And also the discourse that comes out of the movie. What part will be about Ken?

Klimek: Thank you so much for talking Barbie and Ken with us, Emily.

Tamkin: A real pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Klimek: To read Emily Tamkin’s feature story about the history of Barbie, and my piece about groundbreaking Ken dolls through the years, visit SmithsonianMag.com.

And we’re closing out the show, as we do every episode, with a little extra bit of info from my colleagues at Smithsonian magazine. This installment of the “dinner party fact” is best served during dessert.

Ted Scheinman: Hello, this is Ted Scheinman. I’m a senior editor at Smithsonian magazine, and I’m here with a fun dinner party fact about chocolate. And specifically about cacao, the beans from which chocolate is made. The first European to taste cacao was probably Christopher Columbus, and this would’ve been in 1502 off the coast of Yucatan. And it would’ve been during Columbus’ fourth and final voyage. Columbus sees cacao beans in a Maya trading canoe, and he thinks they’re almonds, but then he reaches out and tastes one and is repulsed by the unexpected bitterness. So Columbus is not immediately a fan of chocolate or at least of cacao.

The Spanish were remarkably guarded about their methods for processing and cooking chocolate throughout the 16th century and into the 17th century, such that when they went public in the 18th century, they really, really dominated this European trade in cacao. And also had avoided a significant degree of competition by not telling everyone how magical these beans were.

So it’s sort of a magic bean story … which I love.

“There’s More to That” is a production of Smithsonian magazine and PRX Productions.

From the magazine, our team is me, Debra Rosenberg and Brian Wolly.

From PRX, our team is Jessica Miller, Genevieve Sponsler, Adriana Rozas Rivera, Terence Bernardo, and Edwin Ochoa. The executive producer of PRX Productions is Jocelyn Gonzales.

Our music is from APM Music.

I’m Chris Klimek. Thanks for listening.

Recommended Videos