Keshon Smith, right, a member of the Native American Women Warriors and Army veteran carries the U.S. flag while Carrie Lewis, also an NAWW member and a Marine Corps veteran, holds the POW-MIA flag during the National American Indian Heritage Month observance at Redstone Arsenal, Alabama, on Nov. 13, 2019.

Smith survived an improvised explosive device attack during a deployment to Iraq in November 2004 and battled post traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury throughout her career.

She said joining the Native American Women Warriors organization helped her gain the strength to seek medical help. She is now the NAWW president.

The NAWW are an all-female group of Native American veterans who started as a color guard but have since grown and branched out as advocates for Native American women veterans in areas such as health, education and employment. The members make appearances at various events around the country, serving as motivational and keynote speakers, performing tribal dances, and fulfilling the role of color guard representing all branches of the U.S. military.

VIEW ORIGINAL

As she lay inside the windowless barracks, the explosion that killed one of her closest friends haunted Keshon Barton.

She struggled with simple things; walking to the motor pool, working on vehicles, sleeping at night.

Keshon’s thoughts drifted to her life on the Fort McDermitt Indian Reservation in Nevada. The private first class imagined seeing her close-knit Paiute community once again; and her family riding horses on the dry, rocky Nevada grasslands.

For the second half of a yearlong deployment to Iraq, her unit had moved to the remote Camp Speicher, 100 miles north of Baghdad. There, the Soldier’s platoon provided support for supply runs in and out of the airfield. They’d escort workers onto the camp and provide security.

On Nov. 16, 2004, as Keshon’s vehicle convoy crossed northern Iraq, hidden enemy forces attacked her vehicle in an improvised explosive roadside attack.

Keshon survived, but a part of her did not.

She spent the last four months of the deployment coping with survivor’s guilt over the loss of her fallen friend and post-traumatic stress disorder.

A month after the attack, reality hit the private first class again. She learned that her best friend, a female Soldier, had been hit by an IED attack, leaving shrapnel in her friend’s leg and injuring her foot. When Keshon heard her friend’s call sign on the radio, she immediately rushed to the perimeter gate to meet her friend’s vehicle.

She couldn’t bear to lose another friend.

Keshon still struggled to process the loss that shattered the innocence of a private entering her first brush with war.

“[PTSD] was just eating me alive,” said Keshon, now a retired sergeant first class and president of the Native American Women Warriors. “It was probably the hardest thing I had to face in the military.”

She remained by the Soldier’s bedside until the day the Army flew her back to the states. Her symptoms, however, became so unbearable that her commander moved her to the unit’s command post and then assigned her to perimeter security.

There, the Soldier reflected on the rocky, dry desert land that reminded her of her tribal homelands. The forward operating base sat in a part of Iraq far from a large city or civilization. It took her away from the terrible unknown she had grown to fear.

The thought brought Keshon comfort.

One with the Earth

Growing up on the reservation in northern Nevada, her people’s faith fostered her love of natural things — things connected to the earth; the crops on her family’s farm, the cows and dogs, the rolling desert hills. Keshon learned what Native Americans call the “circle of life,;” which depicts the continuous cycle of life and death and the paths of the sun and moon.

Born to a Paiute-Shoshone mother and Irish American father, Keshon had lived on the reservation for most of her life until her Army enlistment in 2003. Her aunts and extended family’s houses all sat within walking distance from her parents’ home. She grew up going to radios and riding calves.

Before that 2003 deployment, Keshon returned to the Nevada reservation to spend time with family.

A tribal chief performed a ceremonial blessing before she left on her journey to the Middle East.

“You’re never alone,” Keshon recalled the chief saying. “This is our Mother Earth.”

The Northern Paiutes, known as ranchers, traditionally lived in the Great Basin in eastern California, western Nevada, and southeast Oregon.

Keshon said she kept the ways of her people close to her heart as she embarked on a year-long deployment to Iraq in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. She brought a medicine pouch that she wore around her neck for protection.

Now retired Sgt. 1st Class Keshon Smith battled post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury during her 20-year Army career. She finally found healing when the Soldier joined the Native American Women Warriors organization which provides a place where Native women who served in the armed forces can meet and support one another.

VIEW ORIGINAL

Changed forever

That November in 2004, ,Keshon’s convoy embarked on a solitary desert road under a clear November sky.

That day began like any other with Keshon and Ricky carried on their usual morning banter. The Soldiers met in Schofield Barracks, an Army installation settled on the northern side of Oahu, Hawaii.

Ricky a 21-year-old Hispanic-American from the Los Angeles area, impressed his fellow Soldiers with his artistic wizardry with his penciled designs of Aztec and Mexican culture.

Keshon and Ricky bonded over their love of movies and Maroon 5 music. An outgoing Soldier, he’d welcome anyone to play cards and dominos in his barracks room.

The Soldiers’ armored truck had reached the final leg of their destination that morning as they cruised along the remote path. They didn’t see any structure or building as they made their way through the northern Iraqi desert.

Smith didn’t hear the projectile coming.

“The last thing I remember was talking to Ricky,” she said. “And then all of a sudden, everything was black. I felt like I was in a dream.”

An IED blasted Keshon’s truck, forming a crater in the center of the vehicle.

Her vehicle disappeared into a plume of dark smoke. The second gun truck, manned by Keshon’s boyfriend Charles, drive through the cloud to reach the survivors.

Keshon woke covered in blood and pinned to her seat. She couldn’t hear anything except the loud ringing in her ears.

The impact of the blast bended the truck’s cabin. She struggled to regain her bearings to make sense of what happened. “Get out of the truck!” she heard a fellow Soldier say through the smoke.

Keshon could barely decipher the chaos around her.

But she heard the muffled sounds of more rounds and the faint screams of fellow Soldiers. As he grabbed her rifle, the enemy continued to attack her platoon, but she couldn’t see where the rounds hailed from.

She briefly remembers seeing Charles checking on her.

Charles later said he quickly realized that the blood that covered his girlfriend wasn’t hers.

Then they saw Ricky.

They found him in the back of the truck and immediately knew.

The impact of the blast killed him instantly. But Keshon and her fellow Soldiers did not have time to process their friend’s death, as enemy rounds continued to whir.

After the survivors climbed into one of the functioning vehicles, she rushed to the next truck on her convoy to a Soldier who suffered an injury to his face.

Keshon fumbled through her first aid kid to stop the bleeding. She continued to wrap the Soldier’s wounds while applying pressure.

With the enemy continuing to attack, Keshon sat in the back of the truck silently with a blank stare.

She saw a small purple bruise near her knee. Besides that wound, Keshon thought she escaped the blast unscathed.

She hadn’t.

Keshon would see the aftermath of the blast replaying over and over in her mind. She wondered why she had been spared. ”Why me?” she asked herself.

“The average person was not supposed to see what we’ve seen that day, you know?” said Charles. “And you never, ever forget about that stuff. It never leaves our head.”

Aftermath

Hours after the blast, Keshon still felt anxious and on edge. In the days that followed, the Soldier found she couldn’t return to her duties as a truck driver. Initially, her company commander moved her to the gunner spot of her vehicle, but she couldn’t bear it.

The pain had not yet subsided. She could still feel the heat of the truck’s flames. She thought of Ricky often.

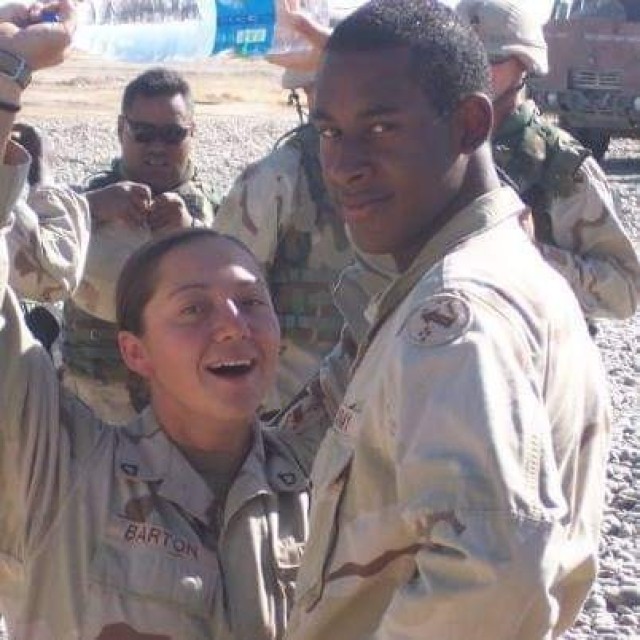

Then-Pfc. Keshon Barton and her future husband, then-Spc. Charles Smith during their 2004 deployment to northern Iraq. Barton, a motor vehicle operator survived an improvised explosive device attack in northern Iraq. One of her close friends, Spc. Ricky Flores died during the blast.

VIEW ORIGINAL

After returning to Camp Speicher Keshon and other members of her unit held a memorial for Ricky. Keshon performed a Paiute ceremony by burning cedar from her medicine pouch. Each Soldier said a prayer for their fallen friend.

When Keshon returned home, she and Charles wed four months later in Oahu. The memories of that November morning still lingered within her. She learned that Charles, too suffered from PTSD after the attack.

Keshon couldn’t bear loud noises and feared large gatherings. Charles said his soft-spoken wife grew more withdrawn.

“I couldn’t go out without … just feeling like I was about to be attacked,” she said. “Or that I might run over something, you know, I just, I was a mess.”

Along with PTSD, Keshon would later be diagnosed with traumatic brain injury.

Keshon Smith admitted she did not seek counseling or professional help at the time. Her life moved quickly. The couple went on to have four children, two boys and two girls. She would go on to five more duty stations and reach the rank of sergeant first class.

“As Soldiers we kind of compartmentalize and don’t seek help until it’s too late,” her now-husband Charles said.

Keshon, however didn’t let the panic attacks deter her career. She even earned an invite to the prestigious Sergeant Audie Murphy Award or SAMA, an honor reserved for the top performing non-commissioned officers who demonstrated exemplary leadership. She led her Soldiers by example, using her actions to teach the finer points of vehicle maintenance rather than words. “She was a high-speed Soldier,” her husband, Charles said.

Keshon kept her inner turmoil within. She would hide her panic attacks from her children and fellow Soldiers.

“I would just be so uptight and so wound up over everything,” she said. “I would have road rage. I was always in a hurry.”

Left, retired Sgt. 1st Class Keshon Smith poses for a photo with her youngest daughter. Right, Smith, now the president of the Native American Women Warriors organization poses with NAWW founder Mitchelene BigMan.

VIEW ORIGINAL

Finding inner strength

In 2011, Keshon learned of a new organization founded by Native American women who served in the military, the Native American Women Warriors Association. She emailed the founder, Mitchelene BigMan, a retired sergeant first class who started an all-female color guard.

After enduring discrimination and sexual assault, BigMan formed an all-native women’s color guard to give American Indian female veterans a support network and the opportunity to perform spiritual ceremony.

Keshon decided to apply for membership and wrote an essay describing how BigMan’s stories of survival had moved her. The writing brought BigMan to tears.

Keshon liked the idea of reminding the nation of native people’s ways, and restoring cultures that have slowly faded from the national consciousness.

From BigMan, Keshon learned the jingle dance of the Ojibwe Nation. During the performance, the dancers wear jingles and make noises that resemble the sound of raindrops. The noises and movements act as remedy for those afflicted by physical or mental illness. The Soldier found the dance therapeutic during her performances. She also became more in touch with her people.

Keshon said participation in the NAWW helped her reconnect with her own culture and heritage, and share her tribe’s teachings with her family and children.

“I was able to lean on my faith,” Keshon said. “I was able to be very spiritual and healing … I was able to just give back to my community and really, show the respect to the elders and those that had taught me our ways.”

Although NAWW members hailed from different background and indigenous tribes, Keshon found comfort in meeting with other women who shared similar combat experiences. She became more involved in the organization during her last two years in the Army, and attended Powwows and special events.

She proudly wore her people’s colorful traditional garments of breechcloth sewn from sagebrush bark.

“She became more outgoing and talkative,” Charles said. “She’s became way more connected with her culture.”

Keshon and the NAWW even performed a virtual ceremonial dance during the inauguration of President Biden. The NAWW become the nation’s first-ever color guard comprised of Native American women.

When the symptoms of PTSD became too much to bear, Keshon would call BigMan and the women of NAWW. BigMan, too suffered from PTSD and the women would share experiences through Zoom meetings and texts. They’ve laughed and shed tears. They learn about their cultural differences.

“[NAWW] is a comfortable place to share personal things like that without judgment and without fear,” Keshon said.

Shortly after, Keshon finally made an appointment to seek professional help while stationed in Germany. She then admittedly took a break from therapy thinking she could manage her symptoms.

The Nevada native didn’t fully come to grips with her grief however, until she took an assignment at Fort Moore, Georgia. A 2022 talk with her then-16-year old son, Jaden. One afternoon, while sitting on the front porch of the family’s Columbus, Georgia home she sat with Jaden. A part of the outpatient program required her to connect with a family member about her mental health struggles.

“My son and I had a tremendous breakthrough, to where he was able to tell me my trauma, made me not be the best version of myself,” Keshon said. “My children were able to tell me how my PTSD was affecting my family. And that was heartbreaking … I just knew I needed help.”

Today Ricky’s death still looms, Keshon and her husband said they think of Ricky each year on the anniversary of his death. This November marked the 19th anniversary of his passing.

“Two decades after the devastating day that took our ‘Ace,’ Spc. Ricky Flores we’ve always remembered, never forgotten,” Keshon said. “Not a day goes by that we don’t feel the loss or pain for our friend, ‘Chuko.’”

“This year, it was especially tough … just after talking [recently] about it,” she said. “I think that it was triggering for me … it had me thinking about it again, and it was just, it was emotionally heavy for me. So yes I have my moments with it.”

She now works at a gym in the Columbus area, where her husband also serves as a firefighter. Jaden will graduate from high school next spring. Keshon said her grief no longer controls her, rather she has found ways to manage it, as she charts life after the Army. She has also succeeded BigMan as the NAWW president. Keshon coordinates color guard performances, White House events and visits to schools where members educate children on Native American culture and history.

Keshon now will openly talk about her past traumas, in order to heal and help others with their struggles, even at the risk of triggering another panic episode.

“On one hand, it’s emotionally heavy, but on another hand, it’s also healing in a way,” Keshon added. “But it never ever, ever gets easier. You know what I mean? It’s a part of my life that’s always going to be there.”

She still returns to the northern Nevada reservation as often she can.

She, Charles and their children recently travelled to Atmore, Alabama for the annual Poarch Creek Thanksgiving Powwow.

She takes her family to spend time with her mother, extended relatives and fellow tribe members at Fort McDermitt.

And there she said, under the embrace of tribal lands she reunites with her people and feels whole again.

RELATED LINKS: