In 2019, a study of almost 7 million people in Denmark found that women were diagnosed with hundreds of health conditions when they were, on average, four years older than men.

Diagnoses for diabetes came four and a half years later, while cancer was diagnosed in women when they were an average two and a half years older.

The researchers surmised that a combination of genetics and environment could be at play but that gender bias might also be partly responsible for the difference.

Lead author Søren Brunak from the University of Copenhagen told NBC News the findings came as a surprise: “Men generally have a tendency to get to the doctor later … So presumably the difference in onset is even larger.”

Minding the women’s health gap

The same year, British journalist Caroline Criado Perez published her book Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias In A World Designed For Men, which lifted the lid on the women’s health data gap. Men outnumbered women 3:1 in 31 medical trials for congestive heart failure over 15 years, for example.

“For millennia, medicine has functioned on the assumption that male bodies can represent humanity as a whole,” Criado Perez told the UK’s Evening Standard. “As a result, we have a huge historical data gap when it comes to female bodies. Women are dying, and the medical world is complicit. It needs to wake up.”

The following year, COVID-19 pandemic disrupted access to healthcare globally, and women were disproportionately affected.

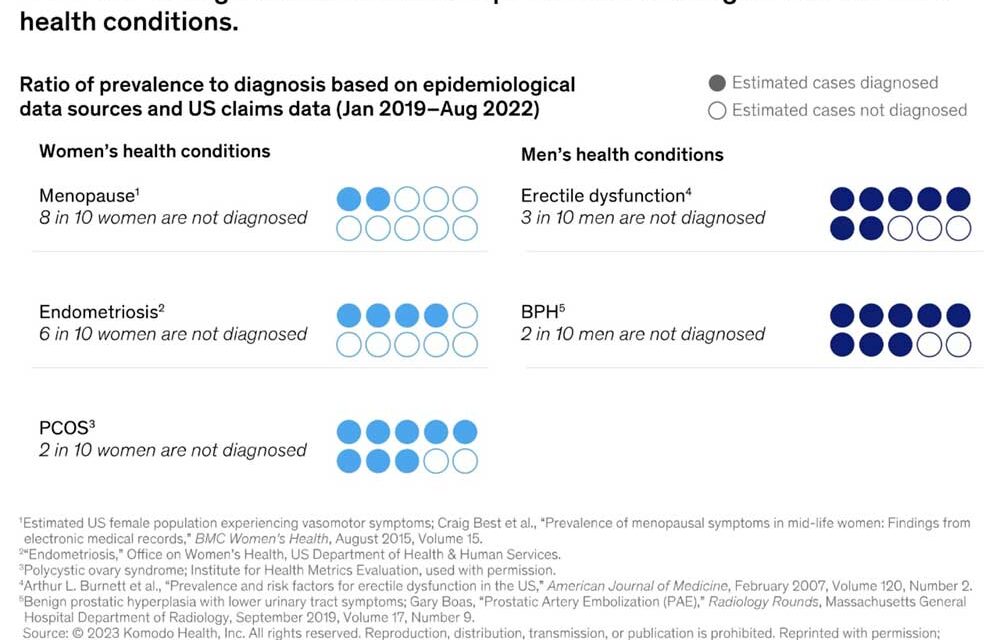

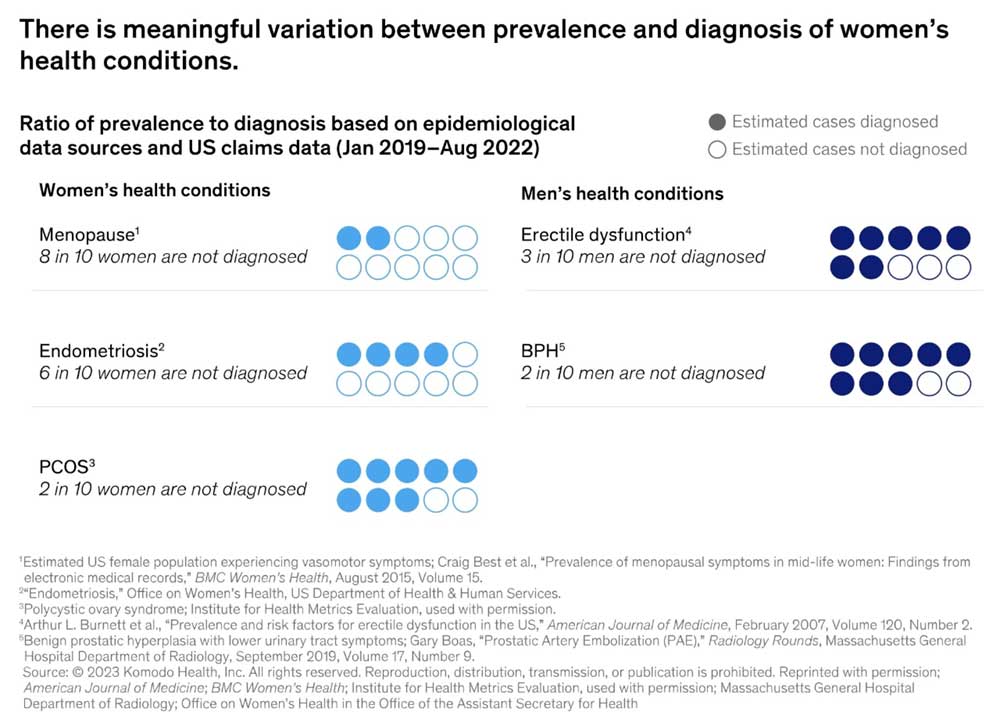

Image: McKinsey

In response, the World Economic Forum launched its Women’s Health Initiative in 2022, working with diverse stakeholders to showcase the socio-economic benefits of investing in women’s health.

Funding for “FemTech” companies is growing, reaching $2.5 billion in 2021, but they only received 3% of all digital health funding, according to McKinsey.

The Forum’s annual Global Gender Gap report noted a slight improvement in the Health and Survival dimension in 2023 – it now stands at 95.9% closed – up 0.2 percentage points compared to 2022. But this is a 0.3 percentage point drop compared to 2006 and varies by region.

Despite the near-parity and the growing availability of data, there are still huge gaps in the diagnosis of women’s health conditions. Here are just three …

1. Heart attack

Women in the UK are around a third less likely to receive a coronary angiogram (which allows doctors to see narrowing or blockages in blood vessels) after a STEMI heart attack, mainly caused by heart disease.

A study published in The Lancet Regional Health – Europe found that women were more likely to die after being admitted to hospital with a severe heart attack, but they were also less likely to be prescribed medication to prevent future heart attacks, such as statins.

Previous research has found women were 50% more likely than men to be given an incorrect diagnosis following a heart attack.

Have you read?

Dr Sonya Babu-Narayan, associate medical director at the BHF and a consultant cardiologist told The Times: “Deep-rooted inequalities mean women are underdiagnosed, undertreated and underserved.”

2. Endometriosis

Endometriosis is referred to as “the missed disease” because so little is still known about it and it’s underdiagnosed.

Globally, it affects 10% of women and girls of reproductive age, but in the US, for example, only two out 10 cases are diagnosed, with diagnosis taking more than seven years – and even longer for Black women.

American filmmaker, lawyer and activist Shannon Cohn recently directed the documentary Below the Belt to shine a light on the condition – and spoke to the Forum’s Radio Davos podcast about her own experience.

Cohn had her first painful symptoms of the condition when she was just 16, but then there was a “yawning 13-year gap of not being believed actually by healthcare providers, being told my symptoms were in my head or part of being a woman, or I was exaggerating”.

3. Autism

Around three times as many boys are diagnosed with autism as girls, and girls are often diagnosed later than boys, or not diagnosed at all, which can lead to mental health problems in adulthood, according to research.

Medical gender bias contributes to this underdiagnosis in women, because girls often don’t present with the same behaviours and symptoms as boys – and they learn to “mask” those that don’t fit with social norms.

“Because females often mask and defy stereotypically autistic presentations, individuals and families must endlessly educate others and advocate for themselves or their children to receive the treatments, supports and accommodations they deserve,” says clinical psychologist, Karen Saporito.

Amira Ghouaibi, Project Lead of the Women’s Health Initiative at the World Economic Forum, believes still more research is needed into why women’s medical needs are not being met before we can achieve gender equality in health.

“Every woman should be able to receive quality care when and where she needs it. We will only be able to achieve this once we examine the state of the women’s health gap, and then identify the biggest disparities to inform strategies and policies towards better women’s health outcomes.”

Written by

Kate Whiting, Senior Writer, Forum Agenda

Website

This article was originally published by the World Economic Forum on 23 October 2023.