CLEVELAND, Ohio — It could be a scene out of Daniel Defoe, Henry Fielding or Masterpiece Theater on PBS.

The newest round of acquisitions at the Cleveland Museum of Art includes “The Dutton Family in the Drawing Room of Sherborne Park, Gloucestershire,” a highly detailed 1772 masterpiece by German painter Johann Zoffany that places viewers inside a fancy 18th-century English drawing room where a card game is underway.

James, 1st Baron Sherborne, and his sister, Jane Dutton, are seated at a fashionable card table made with exotic South American Kingwood. The Duttons’ parents, James Lenox Dutton and the former Jane Bond, help their children, who hold the cards, to strategize their next moves. With hints of sibling rivalry, daughter Jane appears to wait impatiently while her brother shows his cards to his mother.

The men sport powdered wigs. The younger Jane Dutton’s towering hairstyle is trimmed in a garland of pearls. Her mother’s face is framed from chin to forehead in an elaborate white bonnet.

There has been a death in the family. The older Duttons are dressed in black. The children are dressed in lighter shades of mourning. A fire crackles on the hearth. An elaborate Turkish carpet covers the floor.

Cory Korkow, the museum’s curator of European paintings and sculpture said the museum has sought for more than a decade to acquire a painting like the Zoffany, which is known as a “conversation piece,’’ an English genre scene in which a group of people are portrayed in their customary surroundings.

“Even though the environment of the picture may seem incredibly foreign and stuffy, it’s something every one of us can empathize with because of the drama’’ involving the Dutton family, Korkow said.

Korkow was thrilled to learn unexpectedly several months ago from Christie’s, the global auction house, that the Zoffany was available for purchase in a private sale.

“It was surreal; it’s like someone was anticipating” what the museum wanted, Korkow said. “This is the holy grail moment we’ve been waiting for.”

There’s a special reason for Korkow’s excitement. Back in 2018 and 2019, when the museum was planning a reinstallation of its British art galleries, 203A and 203B, it used the widely published and widely exhibited Zoffany painting as the precise inspiration for the project, even though it didn’t own the work at the time and had no hope of buying it.

– A famous book on cabinet design by Thomas Chippendale lies open in a display case in the Cleveland Museum of Art’s newly reinstalled British galleries, near a Joshua Reynolds double portrait flanked by Chippendale candle stands. Steven Litt, Cleveland.comSteven Litt, Cleveland.com

The museum used the same wall color in the Zoffany interior, a bold, tangy shade of turquoise, known as verditer. The gallery also uses detailing and colors for the chair rail, wainscot and arrangement of artworks that are similar to the painting. For that reason, it should look very much at home when it goes on view in the gallery on Tuesday, Nov. 21.

“It’s not a one-to-one match, but the spirit is the same,” Korkow said. “I have seen it in the gallery [during a test hanging] and it looks fabulous.”

Multiple acquisitions, cultural narratives

In addition to the Zoffany, the museum announced the purchase of an important watercolor by the 19th-century French painter Eugene Delacroix, and “The Gift,” a series of 48 watercolor portraits of women artists, writers and curators painted by contemporary African-American artist Emma Amos in 1990-94.

It would be easy to see how all three acquisitions could fulfill multiple agendas relevant to current perspectives on race, colonialism and Western power.

The Delacroix, which depicts a young Black Moroccan woman fetching water, is an example of 19th-century European Orientalism, which featured sensual, exoticized portrayals of Middle Eastern cultures.

A Young Black Woman Fetching Water, 1832. Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863). Graphite and watercolor on wove paper;

sheet: 23.3 x 16.3 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, J. H. Wade Trust Fund, 2023.123Cleveland Museum of Art

The museum’s announcement describes the young woman as “almost certainly an enslaved African,” spotted by Delacroix during his participation in a French diplomatic mission to Spain, Morocco and Algeria in 1832.

The painting is from a series of 18 watercolors made while traveling with Count de Mornay, the French ambassador to the Sultan of Morocco. After the trip, Delacroix presented the series in an album to Mornay. They were dispersed in a sale in 1877 and are highly coveted today, the museum said.

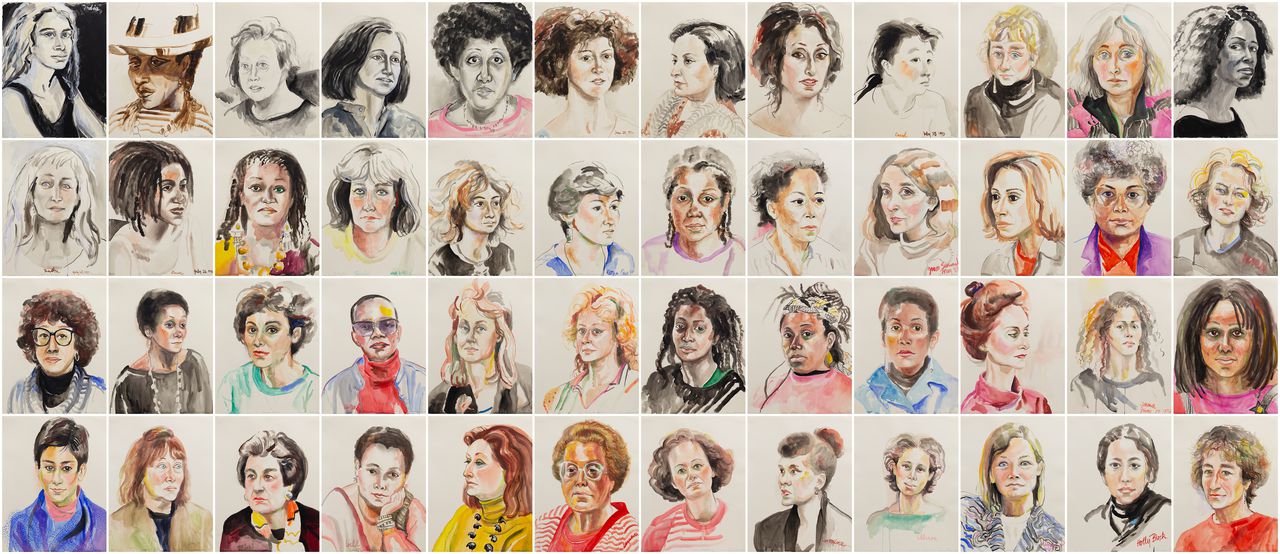

The Amos is a tour-de-force by a contemporary Black artist and a tribute, with strong feminist overtones, to women in her cultural milieu in New York in the 1990s. It adds to two other works by Amos in the museum’s collection, “Sandy and Her Husband,’’ 1973, an oil painting depicting a racially mixed couple, and “Without Feather Boa,’’ a 1965 self-portrait print.

When matted and framed individually and hung together in a large grid, the 48 portraits in the watercolor portrait series will measure roughly 10 feet high by 24 feet wide, the museum said. The museum will display the work in the future in its Focus Gallery, but it hasn’t yet set a date.

The heroic scale of the series suggests a desire to command attention. Aiding that goal is that the portraits sustain a high level of focus and quality across the entire group.

“Regardless of their status, every sitter is treated by Amos with curiosity, care and attention that reflects the artist’s admiration of each woman she represents,” the museum said in its news release.

The Gift, 1990–94. Emma Amos (American, 1937–2020). 48 watercolor portraits; each: 66 x 50.2 cm; overall: 274.3 x 640.1 cm.

The Cleveland Museum of Art, J. H. Wade Trust Fund, 2023.126Cleveland Museum of Art

The museum calls the series a “formidable account of female creativity” driven by the artist’s desire to create a 20th-birthday gift for her daughter, India, that would vividly embody “the value of friendship and community.” As the museum puts it, “The Gift,’’ is a “manifestation of intergenerational feminist community building.’’

Record prices, impeccable provenance

The Zoffany is a snapshot of upwardly mobile landed gentry who benefited from an expanding English empire. The Duttons owned an estate in Gloucestershire, about a two-and-a-half-hour drive west of London. Part of the estate open to the public today includes a 17th-century “stand” or viewing structure, from which spectators could watch hunters and hounds pursue deer across a landscaped park.

The museum has a policy of not disclosing prices for works purchased privately. The Zoffany set a record for the artist in 2001 when it sold at auction at Sotheby’s in London for $4.8 million. A different painting by Zoffany set a higher record of $10.6 million at Sotheby’s in London in 2011. That painting depicts a riverside landscape and a group of subjects, including the famous 18th-century English actor and playwright, David Garrick.

The Cleveland painting has an impeccable provenance, or ownership history. It descended through generations of the Dutton family from 1776 to 1929, when it was sold at auction. From 1936 to 2001, it descended through members of another aristocratic English family. It was in a European private collection from 2001 to 2023, when the museum bought it through Christie’s. The museum said the work is in outstanding condition.

Given Korkow’s longstanding interest in the painting, being able to land it for the museum is a triumph for her and the institution as an example of the conversation piece genre and as the model for the new British gallery makeover.

“It’s exactly what I wanted to evoke with the reinstallation — the idea that you were in an 18th-century English country house,’’ Korkow said. “I had no idea this would ever be on the market. Now you really understand how exciting this is for me.”