This Hispanic Heritage Month, we’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

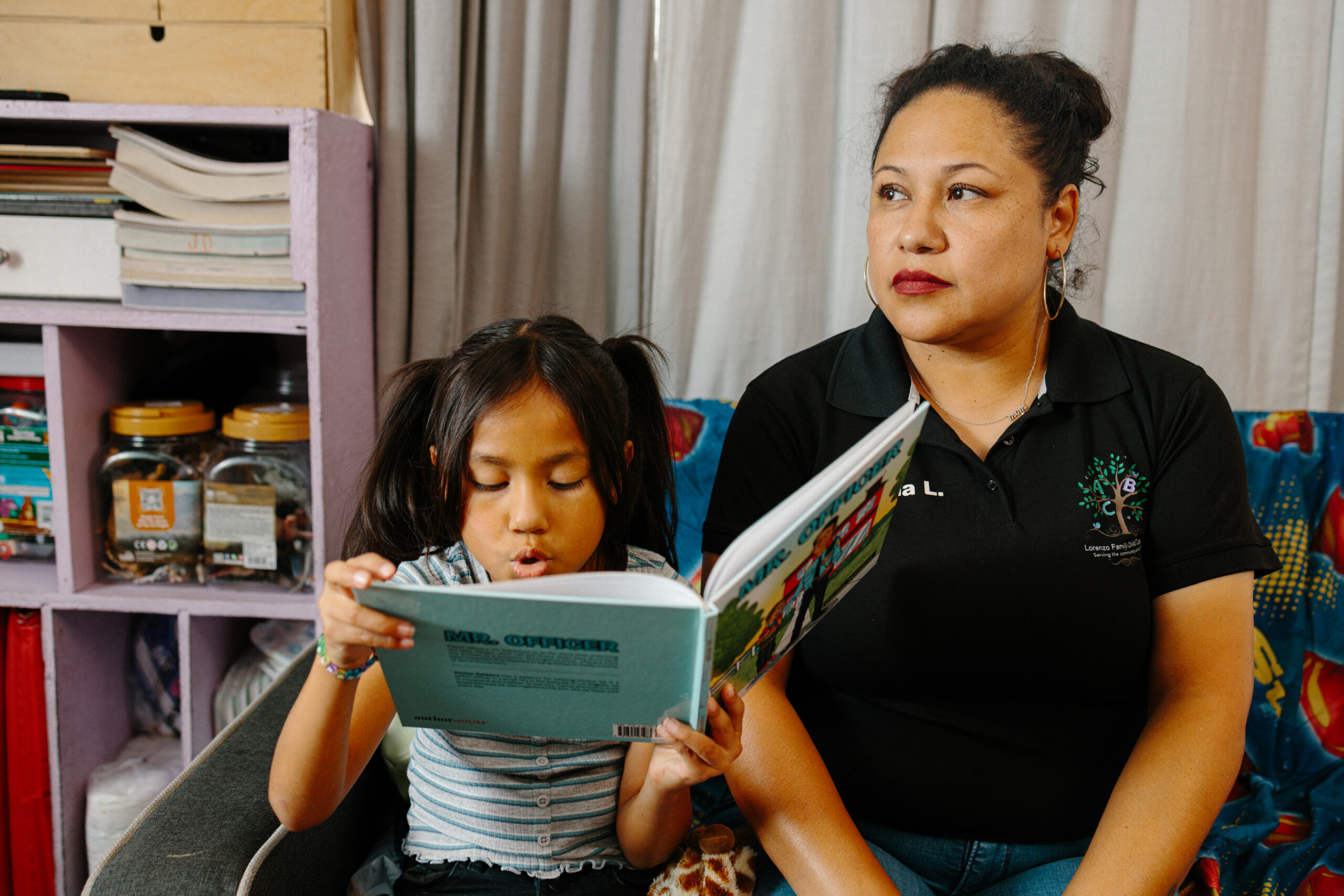

Adriana Lorenzo has been a child care provider for 21 years. To her, that title encompasses so much: Providers like her take on the roles of teachers, nurses and moms to the children in their care. The Lorenzo Family Child Care, in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles, is more than a day care; it’s a second home, a safe place and an environment preparing children for school — and life.

“As Latinas, we were raised to nourish our children,” she said. “So by having these kids, we’re not only seeing them as a kid we have to take care of, or another paycheck that we’re gonna get at the end of the month. We’re looking at these kids as if they were our own children.”

Almost all of the children Lorenzo and her husband serve are Latinx, and many families are low-income and qualify for state subsidies to afford child care. Providers like her have been relying on a spate of pandemic-era funds to stay open. Without them, they risk having to close their doors.

“It’s gonna be hard, because it’s money we were counting on,” she said.

The American Rescue Plan, passed by congressional Democrats in March 2021, included $24 billion in new grants to child care centers to stabilize the industry. But those subsidies were always intended to be temporary, and the last of that largest pot of federal funds is set to expire Saturday.

Over 70,000 child care centers could close, according to one estimate, which would lead to 3.2 million children losing access to child care. Already, many parents have had to cut back their hours or leave the workforce due to a lack of child care options and high costs. More child care closures threaten to further escalate those difficult choices for families — and Latinx families and providers are poised to be especially hard hit.

“It’s a serious crisis that the U.S. is just creeping toward,” said Xochitl Oseguera, vice president of advocacy group MomsRising and its Spanish-language arm, MamásConPoder. “And a child care crisis that can be avoided.”

Caregivers and advocates say that caregiving is not just a deeply ingrained value in many Latinx cultures, but a critical driver of economic prosperity and freedom in their communities. Latinas are overrepresented among child care providers and are also the most likely to have children in their homes. Some states have stepped in to support child care centers or parents who need care, but the loss of federal support leaves many in limbo. And Latina providers and advocates are raising the alarm.

“We are the supply of child care in this country,” Oseguera said. “We take care of children, we open small businesses, we are essential to the child care infrastructure. This is not just, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m not gonna have a place to bring my child,’ it’s, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m gonna have to close my business that takes care of 10 community children, that allows 10 families to go to work. ”

Women and women of color have long dominated the caregiving sector. According to a National Women’s Law Center analysis, Latinas constituted 7.8 percent of the workforce but 17.9 percent of child care providers in 2019. Women born outside the United States were 15.1 percent of the child care workforce, twice their share in the overall workforce.

Cristian Corona immigrated to the United States from Mexico over 20 years ago and worked as a child care assistant before starting up her own center. She opened Little Sprouts Language Immersion Preschool, a bilingual preschool in Los Angeles, about four years ago, shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Child care providers like her are still struggling to stay afloat and hire workers. The child care sector in the United States, unlike public K-12 education, has long been a public good treated as a private market, experts say. In this market, parents face few options and long wait lists while providers and workers earn low wages and often struggle to make ends meet.

“We had a little bit of relief with all of the grants that we had during COVID. But to be honest, a lot of providers had to close down their doors because the income that we make, it’s not enough,” she said of child care workers. “And if you’re a single mother that has a family and child care, and you’re trying to keep up with all of the bills by yourself and all that stuff, it’s pretty much impossible to keep up.”

In 2019, almost 1 in 10 child care workers had incomes below the federal poverty line, more than double the rates for the overall workforce, with Black and Latina women facing the highest rates of poverty — even though many child care providers have college degrees. The average woman working year-round, full-time in child care earned an annual salary of $26,000, or $12.50 an hour, with Black women and Latinas typically earning $25,000, or $12.02 an hour.

“We have people going to work at McDonald’s and they’re making a lot more than whatever we can afford to,” Corona said. “And it’s very challenging to find someone that really cares for the children, and they want to do all of the work that we do for let’s say $16, $17, $18 an hour.”

Lorenzo and Corona, both members of SEIU Local 99, have made several trips to the state capitol this year to advocate and lobby lawmakers for better pay and more funding. Corona has also gotten involved as a member of the contract negotiation team of Child Care Providers United.

“I just feel like around this community, we are spreading the word that family child care providers are not just babysitters, but we’re also educators,” Corona said. “We give resources to people and we’re here to help our community and to share our culture with everyone else.”

Child care workers notched a victory this year when the California legislature allocated $6.5 billion, including $2.9 billion in new funds, into the state budget to increase pay for child care workers and make child care more accessible for low and middle-income families. But both women say there’s more to be done — and they want more providers and parents to join them in the fight for better pay and more investment.

“If we don’t speak up, we’re never gonna win,” Lorenzo said. “We have a saying in Spanish: “El pueblo unido jamás será vencido,” which means, ‘If we all get united, we won’t be defeated.’ And we will persevere.”

The Latinx population in the United States has been growing quickly for decades, and it’s also younger than most other groups, according to the most recent Census data. Latinas are also more likely to have minor children, per The 19th and SurveyMonkey’s 2023 poll.

Before the pandemic, a Center for American Progress study found that about half of Americans and nearly three-fifths of Latinx families lived in a child care desert, defined as a Census tract with a ratio of more than three young children per slot at a licensed child care provider.

In 2022, Latinx households were more likely to leave their jobs and less likely to use paid leave compared to all households who faced disruptions, according to an analysis of Census survey data by the Hispanic Research Center.

Diana Blowers, a mother of two young children in Western New York, is one of the parents who has balanced a career with inconsistent child care and navigating New York’s new expanded child care subsidy program.

Blowers grew up in a large Dominican-American family in New Jersey and described it as a “child-minded” culture where taking care of children is seen as a communal responsibility.

“That’s how I grew up,” she said. “Everyone is in each other’s faces. Your cousins are basically your siblings. Everyone is your aunt.”

But without that family support near where she lives, she’s faced challenges and limited options in finding — and affording — consistent child care for her two sons. Her older son is diagnosed with autism, and she’s currently driving an extra 210 miles per week for his care until both her children can go to the same place.

New York State lawmakers allocated $2 billion toward the child care system in 2022, including subsidies to ease the burden of rising child care costs on families. The legislature expanded eligibility to receive the subsidy to higher-earning families earlier this year, allowing Blowers’ family to continue to benefit from the program through a delicate balance of work hours and salaries.

“We barely qualified for the expanded child care subsidy as long as I only worked part-time, a certain amount of hours,” she said. “It happened to fit and we’re like, ‘OK, thank goodness,’ because that saves us $3,200 a month on child care.”

Blowers, who works at a law firm, and her husband, a process engineer, have made tough decisions about accepting raises and promotions that could disqualify them from receiving the subsidy.

“Any pay bump you get now matters when everything else was incremental, but I had to suck it up,” she said. “Even with that, throughout this entire year, I declined my raise and my husband declined his raise because we are literally on the thinnest of margins. So it’s, it’s been a lot, which sucks.”

After their current contract to receive the subsidy ends, Blowers expects their monthly child care costs to skyrocket from about $200 per month to up to $3,200 a month. Even after accepting a promotion and raise, she says the costs of child care mean she’ll be paying to work. But leaving the workforce during the years before her children start school would mean missing out on years of compounded wages, pay raises and benefits.

“I love my job. I love working with my manager. I love my immediate co-workers,” she said. “I would not want to quit if it were my own choice.”

Reshma Saujani, founder and CEO of advocacy group MomsFirst, said women’s and moms’ economic recovery from the pandemic has been “stunning, quite frankly” — especially given that it happened without guaranteed paid leave, a permanent child tax credit and lasting, meaningful federal investments in child care. Saujani and other advocates are working to mobilize women and moms to lobby their representatives for more funds and make child care a key voting issue in 2024.

“And the fact that Congress is about to let us go over this cliff and set us back again is just unconscionable,” she said. “And moms are going to remember it at the ballot box.”

Advocates say the lack of sustained investment in Latina caregivers reflects an undervaluing of care work — and taking Latinx voters for granted. Latinx voters will be critical to many elections in 2024, including the presidential race. In recent polls, Latinx voters have expressed incredibly high support for expanded child care, early learning and family caregiving funding.

“What I see and I’ve seen for 15 years working in politics is that no one is investing in our communities,” Oseguera said. “They expect for us to be leaning toward a political party and they think that we are monolithic, we’re not. They take us for granted. There’s no investment in our community. And we see it election after election.”

Lorenzo said she wants policymakers to see caregivers who are essential in raising future generations as pillars of their communities.

“I would like for us as child care providers to have the respect that we deserve, and that we work so hard to obtain, because we’re not just babysitters,” she said.