Playwrights are not always keen to talk to journalists. Especially journalists who have critiqued their work.

Yet despite his stature as America’s most prominent Black dramatist, and the frantic pace of his work and travel life, August Wilson often made himself available for interviews. He welcomed the chance to tell his own story, in his own words. He even admitting reading reviews — because, he told me, “I might learn something from them.”

The many hours he spent conversing with Boston Globe theater critic and reporter Patti Hartigan, along with her diligent research and reportage, gives us August Wilson: A Life, the first comprehensive Wilson biography – and a thoughtful, enlightening one. It evokes the August I knew professionally – and reveals many other layers of his extraordinary, and extraordinarily complex, life and art.

Wilson was lionized and his plays showered with prizes (Pulitzer, Tony, New York Theatre Critic’s Circle, etc.). His work was produced across the U.S., and notably at Seattle Rep, Portland Center Stage, Oregon Shakespeare Festival, and other Pacific Northwest companies.

He resided in Seattle for the last 15 years of his prolific and too-short life (he died at age 60 in 2005, from liver cancer). I was theater critic for the Seattle Times for most of that time, and I have my own vivid memories of Wilson, which I’ll get to.

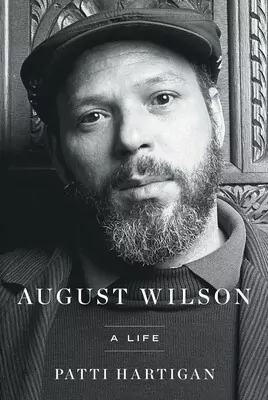

August Wilson: A Life

By Patti Hartigan

$32.50; 544 pages

Simon & Schuster, August 2023

Hartigan’s book opens more than a century before Wilson’s 1945 birth in Pittsburgh’s multicultural Hill District — a place that nurtured him, fired his imagination, and served as backdrop and context for his 10-play Century Cycle. That epic project is Wilson’s great legacy, a brilliantly idiosyncratic, decade-by-decade reflection on African American life through the 20th Century.

Hartigan traces Wilson’s Black ancestry back to North Carolina in the 1860s. His fiercely independent maternal great-grandmother Sarah “Eller” Cutler lived in the remote Appalachian community of Spear, N.C., on land inherited (along with a piano) from her father, a former slave. Working as a midwife, she struggled to support her brood, which endured harsh poverty, and rounds of racist violence and injustice.

Wilson “repeatedly said that he didn’t do any historical research for his plays,” notes Hartigan. He wrote instead from “the blood’s memory” of his Black forbears. He never visited Spear and knew little of the period before his grandmother, Culler’s daughter Zonia, moved to Pittsburgh in the Great Migration of Southern Blacks to the North. Zonia’s daughter Daisy was August’s mother.

Whether or not he knew more than he said, Hartigan points out some intriguing serendipity in Wilson’s plays. The Piano Lesson concerns a family feud over a piano handed down from slavery times. Joe Turner’s Come and Gone (his finest play, according to Wilson and his critics) is set in 1911 among Black men and women who have migrated from the South. And Gem of the Ocean profiles a wise, feisty crone called Aunt Ester.

Wilson’s sui generis blending of mysticism, poetry, near-biblical Black striving and the rich, raw vernacular of common people with big stories to impart, was not naive or simply instinctive. He served a long apprenticeship, and worked diligently at his craft.

He grew up in working-class poverty. His mother toiled as a maid to support August and his five siblings. And his father, Frederick August Kittel (whom he was originally named after), was a white German baker, an alcoholic largely absent from the family. It left a deep wound in his eldest son August’s psyche.

Though fairly light-skinned, Wilson always identified exclusively as Black. (He revered his mother, and bristled if queried about Kittel, or his European heritage.) A precocious, assertive child and voracious reader, he dropped out of high school after too many insults from teachers and racist taunts from white peers. He worked menial jobs, wrote poetry in a classical vein, hung out in Hill District bars and cafes listening keenly to the earthy, bittersweet yarns older Black men regaled each other with.

In the Civil Rights ferment of the 1960s, Wilson and Pittsburgh friends formed a local drama group, Black Horizons on the Hill.

From there, his timeline is well recorded: he turned to playwriting, moved to St. Paul, Minn., for a job as a scriptwriter at a children’s museum, married Judy Oliver, who strongly supported his writing. (His first marriage to Brenda Burton ruptured, but produced a daughter, Sakina.)

In his late 30s, after some theatrical failure, August raised his game — first with an early draft of Jitney, his engaging play about a group of Black cabbies. Then came the watershed drama Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, a scalding tale of 1920s jazz musicians which (after several rejections) won him a spot at the prestigious O’Neill Playwrights Conference, where he reworked the script and honed his craft.

Ma Rainey reached New York in 1984, earning Wilson the first of his nine Tony Award nominations. It was also the first Broadway hit drama by a Black author since Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun. Regional American theaters, which had been presenting few contemporary Black plays, eagerly mounted Ma Rainey. Several went on to stage developmental productions of subsequent plays in the Century cycle – from Fences to Radio Golf.

Hartigan enriches this trajectory with insights into Wilson’s creative process, and revealing comments by his friends, relatives and colleagues. She depicts a man driven by his artistic mission, and dedicated to elevating Black culture. And a man whose life grew increasingly chaotic, between the demands of fame and completing his Cycle.

Though Wilson enjoyed his success, he clung to his humility. And it hurt when old friends (and fellow Black writers) resented his meteoric rise as the “anointed” African American playwright of his generation.

His personal life was complex. He adored his two daughters but didn’t have enough time with them. He was a loving but neglectful (and sometimes unfaithful) husband in three marriages. He feuded with his longtime mentor, director Lloyd Richards, but was largely loyal and generous to close friends and family. He could be charming or shy, but guarded, thin-skinned, and furious over perceived slights. He savored life, but chain-smoked and ignored his health.

To know Wilson and his oeuvre was also to know there was something out-of-time about him. His ruminative, quasi-poetic writing style owed more to Eugene O’Neill than more modern playwrights. He wore the sort of tweed jackets with ties, and porkpie hats, sported by hipster jazz musicians of yore. He was deeply inspired by blues artists like Bessie Smith (the blues “tells me everything I need to know, and I go from there,” he declared), but had no interest in rap or other au courant Black music.

In his blazing manifesto The Ground on Which I Stand, a speech I heard him give at the 1996 Theatre Communications Group conference, Wilson called for more support for Black-run theaters, and rebuked the “color-blind” casting that helped Black actors get cast in play roles historically reserved for white performers. According to Hartigan, Wilson really meant to champion new plays by Black writers, and later regretted the controversy over his casting comments – which sparked his fruitless public debate with dissenting critic Robert Brustein.

Though he called himself “a race man,” Wilson was no separatist. Two of his wives were white. His youngest daughter, Azula (with his wife Constanza Romero, a costume designer and devoted executor of Wilson’s literary estate), is mixed race, like her father.

Wilson’s insistence on a Black director held up the filming of Fences, his most popular play. But he defended the freedom of non-Black playwrights to create Black characters. And in his last years, his closest associate was Todd Kreidler, an aspiring white writer-director he mentored and collaborated with.

My own impressions of August remain vivid, from my first interviews with him in the early 1990s. And I was the first journalist to learn of and report his final illness.

In my first interviews with August he was rather formal. In a softly rumbling voice, he delivered anecdotes about his past that I later realized would be recycled and embellished for many other journalists.

But as Seattle Rep continued to produce his work, we developed a genuine rapport. He was a great raconteur, hilarious at times, congenial and savvy. And though quietly dignified in public settings, he was looser, less scripted one-on-one if he felt comfortable with you. We’d meet up at a favorite August haunt (Victrola Coffee House on Capitol Hill, Mecca Café close to Seattle Rep). And we’d joke, kibbitz about music and baseball, before discussing his newest play.

In 2000, August let me sit in on a Seattle Rep rehearsal of his in-process play King Hedley II, where he dominated the proceedings, with an occasional interjection by the director, Marion McClinton. Conceived as a modern tragedy set in the rubble of homes demolished by the Hill District’s disastrous urban redevelopment scheme, it was a dark unwieldy tale that Wilson was clearly struggling to complete. (It became his least successful Broadway venture.)

August’s mood was much lighter, talking about How I Learned What I Learned. He mocked his own chutzpah for trying to be “the Black Spalding Gray” in this autobiographical solo piece, claiming, “I never wanted to be an actor. I don’t like getting up on stage. I don’t like people staring at me.”

But the play’s short run was a success. (It has since been revised, and performed by others.)

I saw other sides of August when covering his 1998 visit to Valdez, Alaska, where he was honored at the Prince William Sound Community College Theatre Conference.

Rustic, remote Valdez (the earlier site of a horrific Exxon oil spill) had only two Black residents at the time. Wilson increased their number considerably (if temporarily) by bringing an entourage of young Black playwrights from the Lower 48, and several Hollywood “Wilson Warrior” actors (who’d performed various versions of his plays).

In addition to his honoree duties, August spent hours advising and encouraging starstruck novice playwrights. And he acted with gusto alongside the L.A. actors in excerpts from his plays, handily upstaging them.

But most memorable for me was sitting alone with August on the patio of his wealthy hosts’ home. August was more relaxed than I’d ever seen him. He sipped coffee as we chatted, and gazed in awe at the ruggedly majestic vistas of the Chugach Mountains.

There was little room in Wilson’s hectic life for such stillness in natural splendor. He seemed to savor it.

Indelible, too, was a line from his Valdez speech. It crystalized for me what made his plays so accessible to such diverse audiences, in America and abroad. “I try to express through the life I know best,” he said, “the things that are common to all cultures.”

That was one of August’s great contributions: By enlarging and humanizing the life he knew, it resonated for others without losing its specificity.

I experienced that at a performance of Fences in rural Illinois before an all-white crowd. At intermission, I overheard two women talking animatedly. One said of Troy Maxson, the play’s embittered Black father, “He’s just like my dad.”

Not in every respect, surely. But in a way that mattered, and thanks to August Wilson’s genius, still does.

![City of Ellsworth to Pave Water and State Street Monday October 9th [UPDATE]](https://hohmature.news/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/WDEAAM.png)