GARY, Ind.—It has been a bittersweet homecoming for Maya Etienne. Her affection for her birthplace runs deep—despite the decline of the city’s once-robust steel-manufacturing industry.

The chance to be close to family and friends again has been especially sweet—her two children, 14 and 12, became part of the town’s close-knit community since Etienne moved back to Gary from Boston in 2013.

But then there’s the bitter part: shortly after the family arrived, Etienne’s daughter, Roya, came down with a persistent runny nose and began wheezing intermittently as if she were having an asthma attack. The cause, Etienne believes, is linked to the towering plumes of smoke from the city’s steel mill.

“I love being in Gary,” said Etienne, 41, who works with a local group that promotes sustainable economic development. “But at the same time, I’m like, my child needs to be able to live in a space where she can breathe with no issues.”

That, according to researchers, is a challenge in Gary, home of a major polluter–the largest steel mill in the country, U.S. Steel’s Gary Works.

A report published Thursday by the Sierra Club details the toxic emissions and climate pollution from more than 200 industrial facilities–including Gary Works—and the impact of those emissions on surrounding communities.

Iron and steel facilities have the largest impact on human health among the industries analyzed in the report, which also looked at cement, aluminum, and metallurgical coke. These heavy industries undergird the U.S. economy but are also leading sources of hazardous air and water pollution—and greenhouse gas emissions.

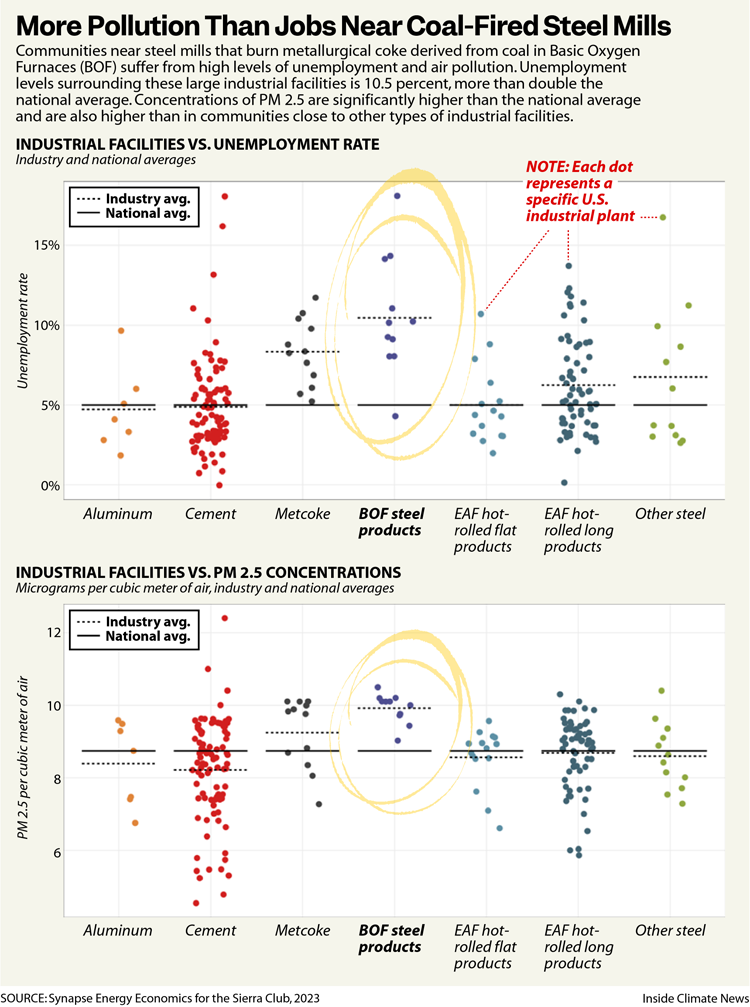

Communities near steel plants that use basic oxygen furnaces—the type of furnace used for primary steel production at the Gary facility—are particularly disadvantaged, with higher unemployment, lower educational attainment and a higher percentage of people of color than all other industries considered in the report, and the United States, on average.

The Gary Works is also the largest emitter of greenhouse gasses among all industrial facilities analyzed in the report.

The report comes as the Environmental Protection Agency is finalizing new regulations on hazardous air pollutants from the production of iron, steel and metallurgical coke, a key ingredient in most primary steel production.

The analysis included socioeconomic factors, including race, average income and employment data in communities surrounding industrial facilities, as well as the impact of potential reductions in air pollution from the facilities on the rate of heart attacks, infant mortality and hospital emissions.

Such comparisons could help policymakers steer more than $6 billion in federal grants made available through the Inflation Reduction Act to help decarbonize heavy industry while advancing President Joe Biden’s Justice40 Initiative, which pledges 40 percent of the benefits of climate and clean energy investments to disadvantaged communities.

“Our project began with an idea of pulling together what was publicly available into one place,” said Yong Kwon, a senior policy advisor with the Sierra Club. “Right now, the greenhouse gasses data, the toxic pollutants data, chemical releases, environmental justice community data, census tract [data], all these things are kind of all over the place. We wanted to have a platform that both policymakers, industry and environmental groups like ourselves could use to engage in the policy discussion.”

The report was commissioned with the aim of cleaning up heavy industry in the U.S. rather than driving it overseas, said Charlie Martin, a program manager with the BlueGreen Alliance, a coalition of environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, and labor organizations.

“We do not want these industries to collapse,” said Martin, who reviewed and provided feedback on the report prior to publication. “We want to support American manufacturing. We want to make it cleaner, and we want to make it greener.”

“The Fire in the Sky“

For Gary residents like Etienne, the emissions from stacks of the Gary Works have been not only a defining feature of the skyline of this city of 70,000, but a source of civic pride—the heart of the city’s economy.

“When I was growing up, a lot of people in my family worked in the steel mill,” Etienne, co-executive director of Calumet Collaborative, recalled. “My grandmother worked in the steel mill, my grandfather—I don’t think I thought much of it.”

And the smoke?

“I used to think that seeing the fire in the sky was cool,” she said, with a grim chuckle. “I always remember kind of seeing this fire in the sky.”

The post-industrial era has been hard on both the mill and on Gary itself, a city that was founded in 1906 by U.S. Steel to house workers at the mill and which is named for one of the company’s lawyers.

A half-century ago, Gary Works employed about 30,000 people; today, there are about 4,300 workers.

Even today, when residents grateful for the mill worry about its impact on the environment, a job at the Gary Works still has cachet.

“It’s still a source of pride to be able to have a job at the steel mill,” Etienne said, explaining how any comment on its adverse health impacts is a delicate subject. Nearly a third of the city’s residents live in poverty, and the jobs are precious.

In Gary, more than three-quarters Black, working at the mill was for decades an important entry point for economic mobility. The city’s most famous residents— the Jackson 5—are tied to steel: the family’s patriarch, Joe Jackson, worked at a nearby mill when he began encouraging his children to play musical instruments.

In Etienne’s family, doctors don’t understand the exact nature of Roya’s respiratory issues—or the cause.

Etienne, who is African American, questions the efficacy of proposed emissions regulations for hazardous air pollutants on Gary Works and other plants.

“I don’t know if they will make a difference in the next 10 years,” Etienne said. “Having a rule in place is not enough. There needs to be people saying, ‘We deserve better quality of life, better air quality, better soil quality,’ and there has to be more than a handful of people saying that.”

Kimmie Gordon, founder of Brown Faces Green Spaces, a Gary-based group that promotes outdoor recreation, said access to natural beauty in Gary and industrialization are colliding with each other, affecting the quality of residents’ lives.

“We have such beauty available to us and access to it, but it’s being tainted by the very thing that made Gary Gary in the first place: the largest steel manufacturer in the nation,” said Gordon.

Gordon’s work as an environmental justice activist is aimed in part at getting people of color access to the area’s many rivers, parks and trails, which they’ve historically been denied.

“Really, Really Old Infrastructure”

U.S. Steel’s Gary Works, a 4,000-acre facility located along the southern shore of Lake Michigan, is the largest manufacturer of primary, or non-recycled, steel in the U.S. Opened in 1909, the Gary Works released 8.1 million metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2020, equal to the greenhouse gas emissions of 1.8 million automobiles, according to the EPA’s greenhouse gas equivalency calculator.

Asthma prevalence among adults and life expectancy in Gary is among the worst in the U.S., with most of the city above the 90 percentile nationally in both categories, according to the EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool.

The Gary Works is also the only steel production facility in the U.S. that uses sinter, or iron ore powder, to make steel, according to a recent survey by the Association for Iron and Steel Technology (AIST), an industry group.

Modern primary steel mills typically feed pellets of iron ore into high-temperature furnaces to make first pig iron and then steel. Sintering, an older method that most U.S. mills have abandoned, uses iron in the form of a fine powder or dust. Sintering was already on the decline in the late 1990s because of environmental concerns, according to a U.S. Department of Energy study published in 2000.

“They’re a really old piece of a really, really old industrial infrastructure. And they emit massive amounts of lead,” said Jane Williams, chair of Sierra Club’s National Clean Air Team, of sintering. “Other mills have given it up—this is like driving a Model T down the road.”

Williams said a 2019 study that examined the baby teeth of young East L.A. residents who lived near an old battery recycling plant found that lead not only stays with those who live in the community, but they’re born with it. Researchers found that a third of the lead in the teeth of a 10-year-old came from their mother.

“You have this population of people who have lived around these industrial facilities for generations, you’re literally going to be able to see the footprint of lead that was emitted in previous generations,” she said. “It’s going to be in their yards. People are going to be exposed to it. They’re going to grow up. And then when the women have the kids,” the lead is passed along and “baked in” to the next generation.

Sintering, according to the Sierra Club report, is associated with significantly higher volumes of toxic air emissions.

Fifty-One Tons of Hazardous Air Pollutants

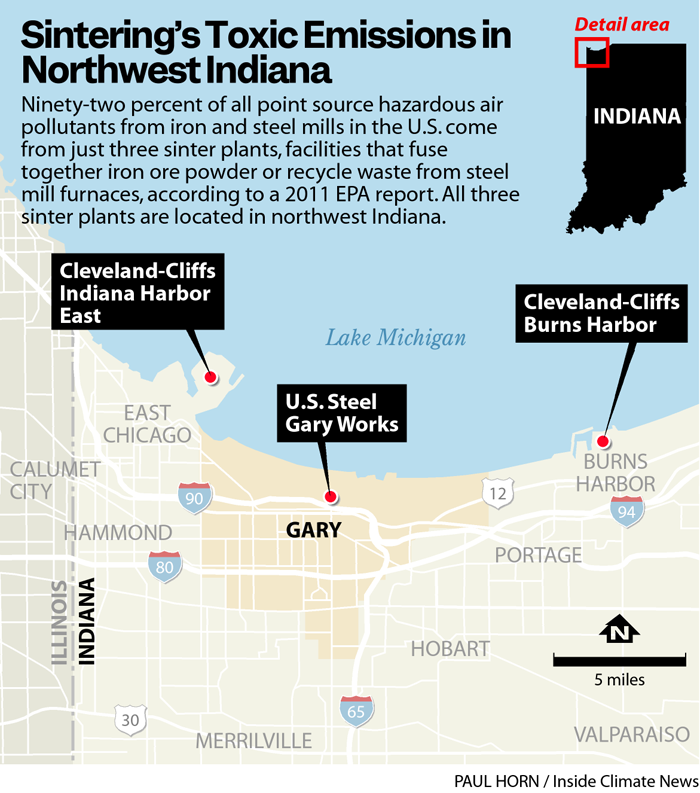

Ninety-two percent of all hazardous air pollutants from the smokestacks or other “point source” emissions from the 11 iron and steel mills operating in the U.S. in 2011 came from just three sinter plants, according to an industry survey conducted by the EPA.

Hazardous air pollutants are toxic substances known or suspected to cause cancer or other serious health effects. Pollution from the Gary Works and two other sinter plants—both also located in northwest Indiana—included 11 tons per year of lead, a toxic heavy metal.

The Gary Works released 51 tons of hazardous air pollutants in 2011, according to the EPA data. The other two sinter plants, one in Burns Harbor and one in East Chicago, are owned by steel manufacturer Cleveland-Cliffs and continue to operate but are only used to recycle hazardous waste from steel mill furnaces, according to a 2021 presentation by Lourenco Goncalves, Cleveland-Cliffs president and chief executive officer.

Amanda Malkowski, a spokeswoman for U.S. Steel, said ore pellets are the primary feedstock at the Gary Works. Malkowski said that U.S. Steel does not use iron ore dust at any of its facilities and that its sinter plant is also only used to recycle waste.

“The Gary Works sinter plant recycles as much as 1 million tons a year of residual products into valuable feedstock,” Malkowski said. “This has a far lower emission and energy impact than mining and making new feedstock.”

Malkowski also said that U.S. Steel has invested more than $40 million in pollution controls and monitoring equipment at its Gary Works facility and spends in excess of $3 million per year to operate and maintain the pollution controls and monitoring equipment. She did not respond to questions about when the pollution controls were installed or when Gary Works stopped using its sintering plant for uses other than waste recycling.

Air emissions from Gary Works in 2021 included 1,019 pounds of lead and lead compounds, according to the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory.

James Pew, the director of clean air practice for Earthjustice, said the three remaining sinter plants at U.S. steel mills are little more than incinerators for hazardous waste and should be shut down.

“Steel mills don’t need sinter plants,” Pew said. “They can operate without them.”

Pew said the EPA has had the ability to reduce emissions from steel mills under the Clean Air Act, but has refused to do so. “That’s the problem. It’s not some insoluble problem that EPA can’t fix. It’s EPA not fixing things that it could fix,” he said.

Kwon, of the Sierra Club, said U.S. Steel needs to do more to reduce its toxic emissions and greenhouse gas emissions.

“We would like to hear how this company—which enjoys a net income in the billions—plans to deploy new technologies to make wholesale changes,” he said.

Kevin Dempsey, president and chief executive officer of the American Iron and Steel Institute, said the American steel industry is the cleanest in the world, due in part to its high reliance on electric arc furnaces that use electricity, rather than coke, and recycle scrap steel, a less energy-intensive process than manufacturing primary steel.

Electric arc furnaces have lower emissions than the furnaces used for making primary steel. However, secondary, or recycled, steel cannot be used in all applications. For example, most of the steel used to manufacture automobiles requires higher quality, primary steel.

Dempsey said the manufacturing of primary steel in the U.S. is also cleaner than in other countries because of the U.S. industry’s reliance on iron ore pellets.

“Integrated steel mills in the U.S. are primarily fed by domestically sourced iron ore pellets compared to CO₂-intensive sintered ore used in China and elsewhere,” he said. This results in significantly lower emissions of carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide and particulate matter, he said.

Dempsey also said the report’s claims about health risks to populations near iron and steel facilities are directly contradicted by EPA’s own risk assessments. “According to EPA’s detailed risk assessments, specifically on steel and coke facilities, the human health risks from these facilities are well below the risk levels set by Congress in the Clean Air Act,” he said.

Do the EPA’s Proposed Regulations Go Far Enough?

The EPA is currently updating its regulations for hazardous air pollutants from iron and steel manufacturing with a final rule expected later this year.

Proposed amendments include an approximately 25 percent reduction in hazardous air pollutants from “fugitive” emissions or accidental releases of emissions from sources other than smokestacks.

Environmental advocates say the proposed emissions reductions do not go far enough.

“I’m not satisfied with EPA’s proposal,” said Hilary Lewis, steel director at Industrious Labs, an environmental organization. “They need to be holding these facilities to the highest possible standard and protecting clean air for surrounding communities.”

EPA officials did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Dorreen Carey, a Gary resident and founder of Gary Advocates for Responsible Development, or GARD, said the estimated emissions reductions are not enough for communities like Gary, where residents have been exposed to hazardous air pollutants their whole lives and are seeing serious health impacts.

“When EPA considers the cost of achieving these reductions, their priority should be the costs that residents are suffering from long-term damages to community health and the environment,” Carey told EPA officials at a hearing on the proposed new rules in August.

A 2019 assessment by the EPA shows that fugitive emissions from iron and steel mills could be reduced by approximately 65 percent.

“We’re asking EPA to be more ambitious as it revises the rule, and to require a 65 percent reduction in hazardous air pollutants,” Lewis said.

The proposed regulation does call for “point source,” or smokestack, limits on five hazardous air pollutants from sinter plants that are currently unregulated, but concedes that “we expect no control costs or emissions reductions as a result of these emissions limits.”

While new regulations appear unlikely to reduce emissions from sintering, the Inflation Reduction Act and its $6.3 billion in grants set aside for heavy industry, could provide an opportunity for older steel mills to invest in far cleaner technology.

One alternative is direct reduced iron, which comes from steel mills that transform iron into steel without coal-based metallurgical coke. The process, which relies on natural gas instead of coal, is more energy efficient and has far less toxic emissions. The direct reduction of iron can also be fueled by hydrogen, which can be generated from renewable energy, allowing for what advocates call “fossil-free steel.”

Three small U.S. mills–one each in Texas, Louisiana and Ohio–currently use direct reduced iron powered by natural gas.

However, a 2022 report by the U.S. Department of Energy cautioned that while direct reduced iron worked well at the pilot scale, use of the technology in larger mills remained uneconomical.

Lewis said Inflation Reduction Act funding could help industry scale-up the technology while transitioning to hydrogen power.

“We are in a crucial moment for transforming the steel industry,” Lewis said. “It’s going to require companies that have been doing things the same way for decades, if not centuries, to make big investments in their facilities, in the communities they operate with and in the union workers that operate their mills safely. Getting that investment in the next few years is going to be critical to a clean steel industry in the future.”

Change in Gary

With newer environmental activism in the city and EPA’s proposed rules only addressing a fraction of industrial emissions, Etienne is aware that clearing the air in Gary will be a slow process.

Etienne, like many others in the city, wants to stay in Gary, even with its pollution and socioeconomic hardships. Gary’s architecture, charming houses, small-town atmosphere and biodiversity have retained residents, said Etienne. “Residents love the city even if they don’t think they can thrive in it.”

“When change happens at the top, it may take a very long time to trickle to the bottom where it’s felt, where there is impact,” she added. “The progress is happening, but there’s always more room to grow.”