This article was first published by Wisconsin Watch.

When her daughter was born weighing just 1 1/2 pounds, Dr. Jasmine Zapata experienced firsthand the danger she now spends her professional life battling: Wisconsin’s stubbornly high rate of preterm birth and mortality, especially among Black babies.

Zapata works at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health as a pediatrician and public health researcher. For the last two years, she also has served as the state epidemiologist for maternal and child health and chronic diseases at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS).

Her second child, born prematurely at just 25 weeks of gestation, faced several life-threatening illnesses in the neonatal intensive care unit. As Zapata knows better than most, complications caused by prematurity are the leading cause of Black infant mortality in Wisconsin.

“She was almost a statistic,” Zapata said. “I was a statistic with my birth outcome … the one about college-educated Black women having higher rates of preterm birth compared to white women who don’t finish college.”

Her daughter is now 13 years old and “thriving,” but the experience still fuels her passion for combating inequities in maternal and child health.

Dr. Jasmine Zapata, chief medical officer for community health and state epidemiologist for maternal and child health and chronic diseases at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, sits n her office on July 12, 2023, in Madison. Factors such as chronic stress, adverse childhood events, racism and lack of health care access can significantly affect pregnancy outcomes, Zapata says. (Credit: Drake White-Bergey / Wisconsin Watch)

Wisconsin has one of the highest mortality rates for Black infants in the United States. The two main causes of death within the first year of life for Black infants are low birthweight and sudden unexpected infant death, according to a 2023 DHS report.

The report calls for more parental education around safe sleeping habits (babies alone on a surface on their backs, free from soft objects and loose bedding), prioritizing breastfeeding when possible and better access to prenatal and postpartum care.

Research, including at the University of Wisconsin, has highlighted societal factors — including stress caused by poverty and racism — as major causes of negative outcomes for Black babies. Wisconsin is home to outsized Black-white disparities across society, including in education, wealth, health and housing, and the justice system.

Mortality rate remains high

In 1990, Black infants in Wisconsin were 2.7 times more likely to die within a year of birth than white infants in the first year of life, according to DHS. Three decades later, Black infants in the state are three times more likely to die than white infants.

“This isn’t new news,” said Theresa Duello, a reproductive cell and molecular biologist who researches misconceptions of race, a social construct, in genetic studies.

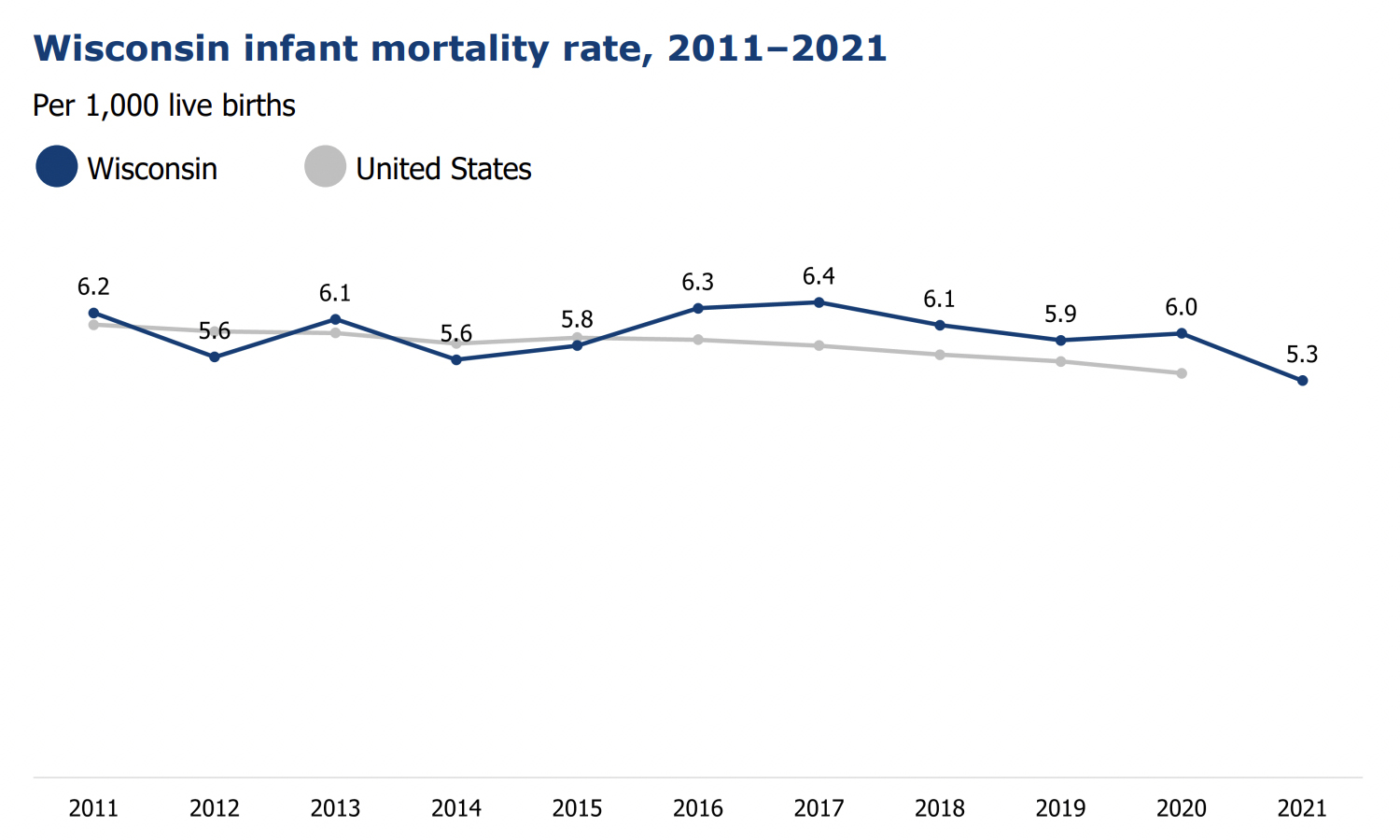

The overall rate at which infants die during the first year of life in Wisconsin in 1990 was 8.4 deaths per 1,000 live births. By 2021, that number dropped to 5.3 deaths per 1,000 live births, similar to the national rate.

A chart shows the annual infant mortality rate in Wisconsin and at the national level between 2011 and 2021. (Credit: Courtesy of the Wisconsin Department of Health Services)

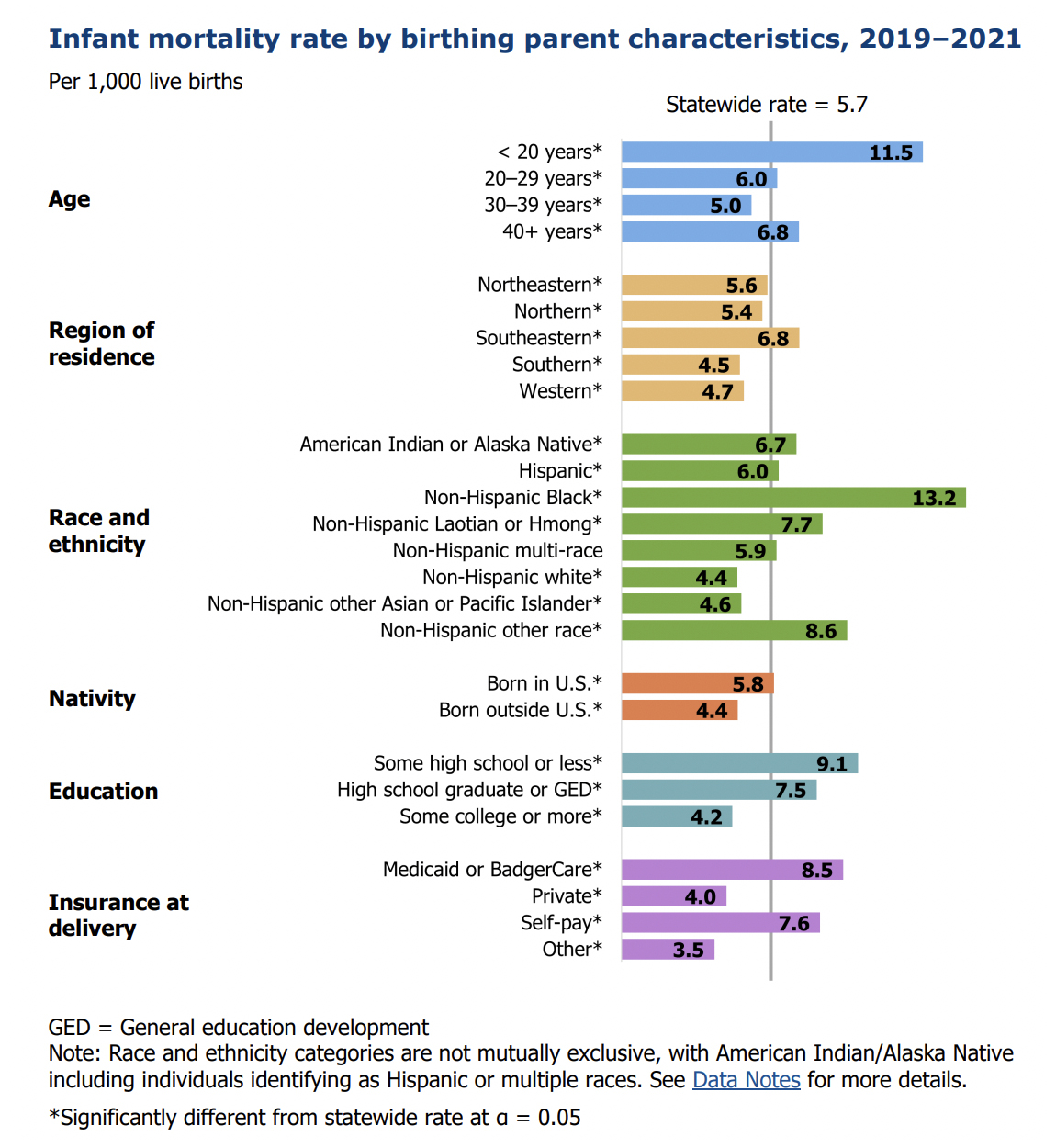

Negative birthing outcomes for Black infants have not improved as quickly as those for white babies.

Among white infants, the rate dropped from 7.2 to 4.4 deaths per 1,000 births between 1990 and the 2019-2021 period — a 39% decrease. Among Black infants, the rate dropped from 19.7 to 13.2 deaths per 1,000 live births over the same period, a 33% drop and still triple the rate for white infants.

“I think we should reexamine how we take responsibility for this,” Duello said.

Preterm birth is top cause of infant deaths

Preterm birth, those occurring before 37 weeks of pregnancy, is the leading cause of newborn mortality.

Wisconsin’s rate of neonatal deaths due to preterm birth was 21% above the national average in 2018. That year, 15.6% of Black births were premature, compared to 9% of white births.

Pregnancy outcomes can differ widely among people of different races and other demographics. Black infants in Wisconsin, for instance, are three times more likely to die than white infants. (Credit: Courtesy of the Wisconsin Department of Health Services)

Low birth weight — infants less than 5 pounds, 8 ounces — and prematurity are both associated with infant mortality, Duello noted.

Low birth weight is often associated with intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), when the fetus is smaller than expected for the number of weeks of pregnancy. Researchers hypothesize that an increase in the hormone cortisol during pregnancy may harm blood flow to the placenta, compromising access to nutrients and impairing fetal growth.

When low birth weight babies are born in consecutive generations, some may incorrectly assume the issue is genetic, Duello said. But if pregnant women in the same family face great stress over the generations, such as poverty, lack of health care and racism, they will more likely have high cortisol levels — and likely deliver a small baby. Addressing such stressors could improve pregnancy outcomes, research shows.

Stress blamed for racial disparities

Mothers of color disproportionately live in areas with fewer resources and thus may face greater stresses that increase the odds of negative birth outcomes, DHS says in a 2018 report.

“The Black-white difference in infant death is considered an inequity because its causes are systemic, avoidable and unfair,” the report says.

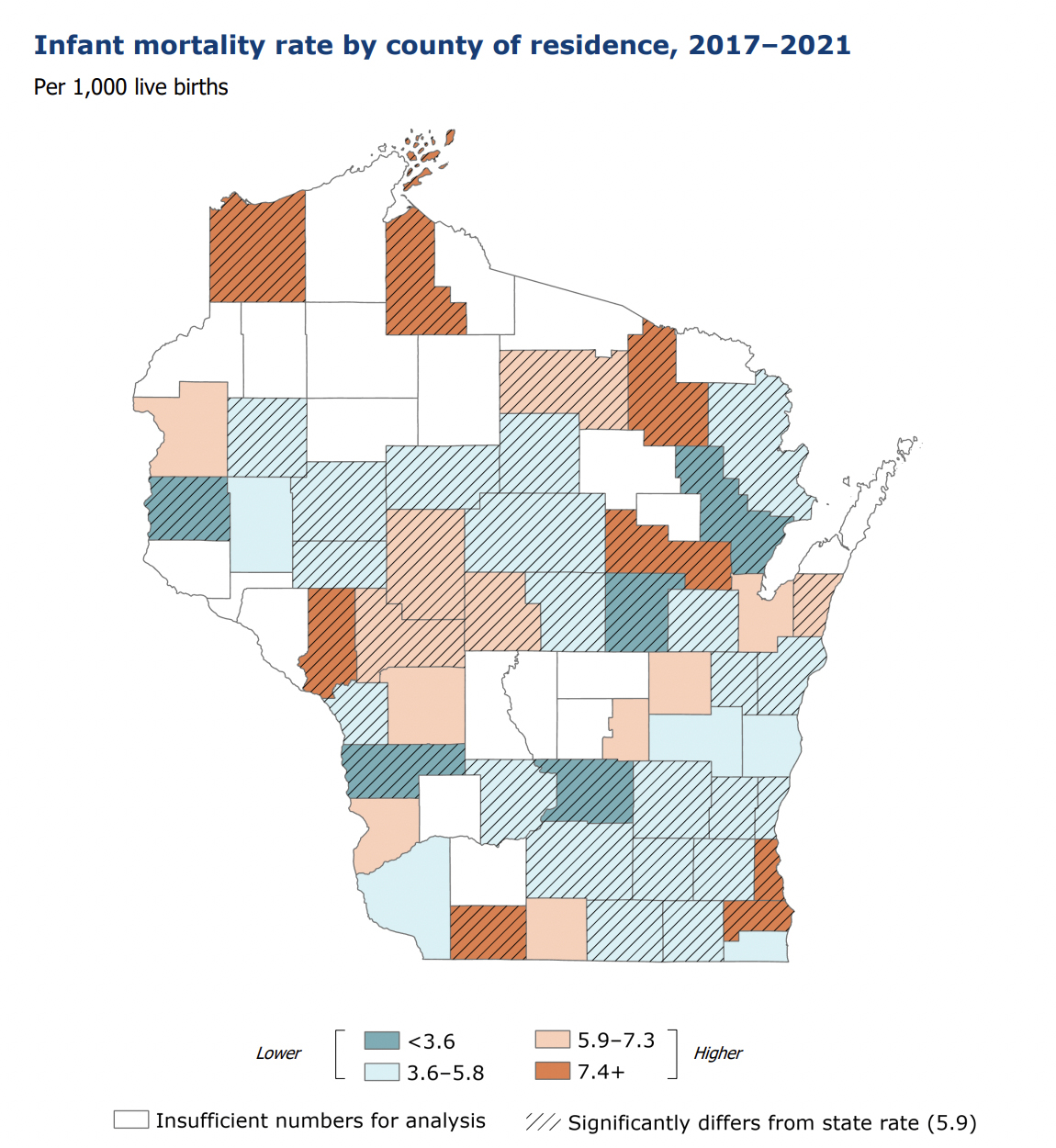

A map shows the infant mortality rate in Wisconsin by county between 2017 and 2021. (Credit: Courtesy of the Wisconsin Department of Health Services)

While poverty affects stress levels, a California-based study suggests racism can play an even bigger role in infant mortality disparities than wealth. In California, the wealthiest Black parents lost more babies on average — 437 per 100,000 births — than the poorest white parents: 350 per 100,000 births.

“We know what to do. We lack sufficient intent,” Duello said. “And that doesn’t mean there aren’t good people working really hard.”

Infant mortality in Wisconsin’s state budget

The federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and the Title V Maternal and Child Block Grant program provide key resources for reducing maternal and infant mortality rates in Wisconsin, according to DHS.

Thirty community organizations — eight of which are based in Milwaukee County — have received grants to reduce infant and maternal mortality rates in Wisconsin.

But ARPA funds are not permanent.

In his 2023-2025 budget, Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers proposed $5.7 million over two years in grants for community organizations working to lower maternal and infant mortality. The funding would have also supported fetal and infant mortality review teams and grief and bereavement efforts.

Evers’ proposal would have helped community-based grants stretch beyond the time frame of ARPA and built on the work started with the ARPA-funded community grants, according to Elizabeth Goodsitt, a DHS spokesperson.

But the Wisconsin Legislature’s Republican-controlled Joint Committee on Finance removed the provisions along with hundreds of others before Evers ultimately signed the budget in July. The final budget allocated $222,700 per year for “reducing fetal and infant mortality and morbidity” — the same level DHS has received for more than a decade.

Doulas seen as a solution for improving pregnancy outcomes

A 2014 study found better birth outcomes for Black and white mothers who participated in Healthy Start, a community-based federal program involving home visits, health information and access to medical and community services.

Another approach is the use of doulas: support people during pregnancy, labor and birth. Hanan Jabril, a community doula and sexual and reproductive health and rights educator in Madison, said a doula’s role is to support and empower the patient to facilitate a safe pregnancy and birth.

“We don’t speak on behalf of the patient, but we can help facilitate conversations between the patient and the provider,” Jabril said.

One goal is to reduce “obstetric violence,” which refers to harm inflicted during or in relation to pregnancy, labor and the postpartum period, sometimes by providers who hold implicit biases against people of color.

One example Jabril observed: a patient who was denied pain medication in the hours after a cesarean section after a provider suspected “drug-seeking behavior” — contrary to what some of the patient’s nurses thought. Although the patient advocated for herself, the experience showed the potential harm of implicit bias and the need for doulas, Jabril said.

Hanan Jabril, a community doula and sexual and reproductive health and rights educator in Madison, says a doula’s role is to support and empower the patient to facilitate a safe pregnancy and birth. “We don’t speak on behalf of the patient, but we can help facilitate conversations between the patient and the provider.”(Credit: Drake White-Bergey / Wisconsin Watch)

The presence of doulas can improve birth outcomes. Doulas have been shown to decrease cesarean sections — surgical procedures with higher risks than nonsurgical births — by anywhere from 28% to 56%, according to DONA International, the largest doula-certifying organization.

People partnered with doulas often forgo epidurals or other pain medication, and they are four times less likely to deliver a baby with a low weight, according to a 2013 study.

The price of doulas ranges widely depending on the type — for instance their availability before or after a birth. Although most insurance companies do not cover a doula’s full cost, Jabril considers them “always worth it.”

Patients in need of financial help have options. The city of Milwaukee, for instance, since 2019 has matched residents with free doulas through its Birth Outcomes Made Better program.

Some doulas-in-training or volunteer doulas are willing to work for free. Jabril provides free services.

Wisconsin DHS recently disbursed almost $1 million to four community organizations that train doulas or provide doula services. Two of those organizations — both based in Milwaukee — received more than $700,000 for doula workforce development. They include the WeRISE Community Doula Program, which provides free services.

Zapata admits her work to improve birth outcomes often is “daunting” and “discouraging,” but it’s also important.

“And it’s important for us to remember that behind all of the statistics and numbers these are real lives and real families that are forever impacted,” she said.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.