Birch is fortunately not hampered by the wrist injury sustained in a tumble on one of his daily eight-kilometre runs and decides to have a lunchtime breakfast – bacon, poached eggs, hash browns and toast. I plump for penne puttanesca with tomatoes, anchovies, olives and garlic. We share a large bottle of sparkling mineral water.

Penne puttanesca at Marios.Credit: Eddie Jim

We’re discussing domestic violence, the subject of the Indigenous writer’s fourth novel Women & Children. Set in 1965, it focuses on 11-year-old Joe Cluny, a scallywag frequently in trouble at his Catholic primary school, his sister Ruby and their mother Marion, a single parent. One day, Marion’s younger sister, Oona, turns up at the door with clear signs of a beating inflicted by her flash boyfriend, Ray Lomax.

Joe’s grandfather, Charlie, with whom he is spending the days during the summer holidays, is horrified by what has happened to his daughter and tells his scrap merchant friend Ranji about his frustrations. How can the family get Oona out of Lomax’s grip?

“We use that term (domestic violence),” Birch says, “because it’s a crime committed overwhelmingly by men against women and children”. “Some of those children are male children.”

One of them was Birch, who says he is now at peace with his childhood. His father died a couple of years ago and although they weren’t entirely estranged, it allowed him to forgive his father for his transgressions. “About a year ago, I picked up his ashes and took them home on the tram and I felt most at peace.”

He makes the point in an author’s note that the novel’s story is not that of his own family: “It is a story that witnesses both the trauma of violence and the freedom that comes with summary justice, even when satisfaction is a momentary experience.”

Tony Birch, 7, in the foreground, in Fitzroy in 1965. Behind are his brother, Brian (left), his sister, Deborah (centre) and a friend, Jimmy.

But Joe’s experience with the Catholic Church does mirror Birch’s own. He was an altar boy at All Saints in Fitzroy, but a believer only out of fear – of eternal damnation and of being belted by the priests at school.

“I was too scared not to believe in God. It’s a terrible indictment to think that the only way you get children to accept religion is through fear. It sounds odd, but I could cope with the belting … The literal belief in hell, the literal torturous experience, which is the way it was instilled, that was frightening.”

Birch has written previously about what he calls the hypocrisy of masculinity – that obsession with bravado and toughness. This time he wanted to write a story with two strong female characters, Marion and Ruby, and two older men, Charlie and Ranji. “I did want to write about the value of loving men – men who love their families – because although Charlie in particular is from a very masculine, aggressive culture, he is incapable of that violence himself.”

Loading

Birch wanted to give Charlie some grace because he knows he is not capable of standing up to Lomax. He says Charlie’s a lovely grandfather. Of course, the other factor is that since his last novel The White Girl (2019), Birch has had two more grandchildren. He looks after his eldest, Archie, each Wednesday; they always go to Marios for morning tea. The waiting staff all know Archie and today wondered where he was.

Birch says he adores the gentle, loving relationship with his grandchildren – it’s so different from his childhood. “I do not feel at all traumatised by my childhood but any time I’m with my grandchildren, if they could have witnessed or experienced violence, even thinking about that traumatises me.”

What he loves is story, character and plot. When I observe he is not a flamboyant writer, he replies “or person … I am driven by the idea of unambiguous, direct prose”. “It’s the way I like to write.”

In 2020, Birch left his position at Victoria University, where he researched climate change and Indigenous knowledge systems. He thought he had retired. But last year, the 66-year-old applied to follow Alexis Wright as the Boisbouvier chair in Australian Literature at the University of Melbourne. He has the gig for three years.

While he doesn’t do classroom teaching, he sees students all the time and gives lectures, including one on the work of Kim Scott, his fellow Indigenous writer about whom he’s writing for Black Inc’s Writers on Writers series. He is also involved in Melbourne GP Mariam Tokhi’s narrative-medicine course at Melbourne University, which aims to help doctors and medical students respond more empathically to patients.

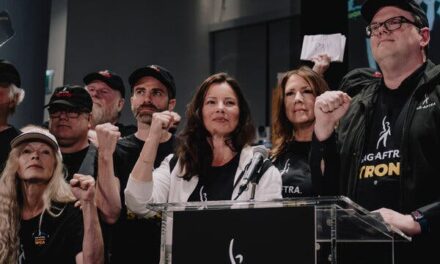

Tony Birch says the positive thing to emerge from the referendum was the voices of a new generation of Aboriginal people. Credit: Eddie Jim

And he’s part of an international project with the University of Leicester to trace the descendants of a shipload of men from Barbados who were transported to Van Diemen’s Land. It’s no mystery to him, however; it’s a connection he has known all his life. “I am a direct descendant of a man called Prince Moodie and that story is integral in the family. It was not discovered on ancestry.com.”

As he told a university roundtable when he was last in Britain, “my great, great uncle, Les Moodie, was Australian Bantam Boxing Champion around the time of the Great War. Les lived to the age of 93 and died in the early ’70s … Les would tell us many stories. And that of Prince Moodie, who had found his way to Van Diemen’s Land from Barbados and later migrated to Melbourne, was talked about often.”

Birch had hoped that Victoria and New South Wales might have voted for the Voice, but “the fact that it went down didn’t surprise me”.

“The level of racism didn’t surprise me. When you think of someone like Peter Dutton and when he was minister for Home Affairs how he played the race card around refugee and asylum seekers … why people would think he wouldn’t behave that way is beyond me.” What Birch did find encouraging, however, was the emergence of new Indigenous commentators.

Loading

“I saw a lot of voices of a new generation of Aboriginal people, young men and women who were very articulate – regardless of what side they were on – very energetic, and to me it indicates that this new generation of thinkers, activists and creative people need to be given much more game time.”

Indeed, Birch is in no doubt: “The older generation need to take a step back. It’s up to these younger people to think of new ways of engagement. It’s not about being pro or anti-Voice for me; it’s about there being potential for a real shift.”

As we think about leaving Marios, Tony Birch tells me he’ll be starting a new novel the next day, the day after Women & Children is published. “Every book is started on November 1. For the last few weeks I think I could have started, but then I get really superstitious.”

Helpfully, he has an ending for it in mind. “Not the ending, but an ending … You don’t just get in the car and start driving.”

Women & Children is published by UQP at $32.99

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.