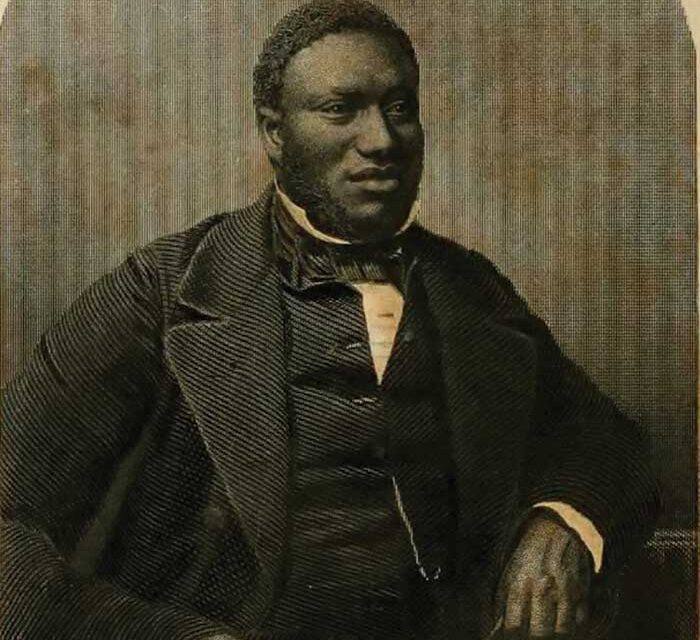

The remarkable life of Samuel Ringgold Ward.

R.J.M. Blackett’s new biography examines the life of the abolitionist, newspaper editor, activist, and globetrotter.

We need more Black biographies. Scholars spend a significant amount of time writing about historical moments and movements, but in the United States, the study of individuals is often reserved for US presidents, other well-known political figures, and celebrities. In terms of Black biographies (or the lack thereof), the numbers are astonishing: We are still living in an era of firsts and onlies. Some of the best-known Black figures of the 20th century have had only one biography written about them—or none at all. Alex Haley wrote or cowrote two of the most notable books of the century, The Autobiography of Malcolm X and the iconic Roots: The Saga of an American Family, and yet the only in-depth biography of him wasn’t published until 2015. There is still no serious biography of Coretta Scott King or any of the women in the Black Panther movement.

Books in review

Samuel Ringgold Ward: A Life of Struggle

When it comes to the 19th century, the numbers are even worse. Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman have only a handful of biographies, and none of them were written by Black historians. Biography matters: It reveals the importance of individual experiences and contributions. Too often, the Black abolitionist movement gets boiled down to the leadership of Douglass and Tubman—and while their lives were long and their contributions innumerable, there are dozens of other Black abolitionist leaders who have earned the right to be household names, such as Lewis Hayden, Charles Lenox Remond and his famous sister Sarah, Charlotte Forten Grimke, William Cooper Nell, and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin. Yet very few have had books written about them—and the hard truth is that this dearth of biographies is not always about a lack of sources.

Yale University Press’s new “Black Lives” series seeks to address this hard truth. Over time, it plans to publish a set of biographies of remarkable but overlooked Black figures. Fittingly, the first in this series is R.J.M. Blackett’s book on the abolitionist, newspaper editor, and minister Samuel Ringgold Ward. Ward is an interesting choice for a number of reasons. His was not exactly a “rags to riches” story, and he had only a few professional victories. In fact, he struggled for most of his life, working as a teacher, preacher, lecturer, and editor. Ward had a nomadic lifestyle, and his multiple jobs suggest that he never managed to make a enough money to sustain himself and his family. But as an activist, he pushed both white and Black Americans to rethink what freedom should entail. He challenged the United States and even Canada to live up to a creed of liberty and equality. As Blackett demonstrates, Ward’s life was one of precarity and hardship. By telling his complicated story, Blackett also helps us understand Black persistence in the face of slavery and inequality. Despite the challenges Ward faced, he never quit his fight for justice.

Like Douglass and Tubman, Samuel Ringgold Ward was born enslaved on the eastern shore of Maryland. In 1818, when he was 3 months old, his parents escaped slavery with their child in tow, heading first to New Jersey and later settling in New York. Yet even in the “free” North, Ward grew up in a world darkened by the violence of slavery and fierce racial discrimination. Though he lived free and was educated in the African Free School in New York City, he was a fugitive in the eyes of the law.

As Ward got older, he became dedicated to the abolition of slavery and to securing the rights of free Black Americans. He was working as a teacher in Black schools when he met his future wife, Emily Reynolds. They were married in January 1838 and later raised a family.

As an activist, Ward didn’t focus on chattel slavery alone. He was a man of principle and Christian values and opposed the Mexican-American War in the late 1840s. He also promoted temperance and self-control and supported granting diplomatic recognition to Haiti. He believed in social and spiritual integration, but he was also, at times, something of a contrarian. He baffled fellow Black abolitionists like Douglass, Charles Lenox Remond, and Martin Delany when he chose to speak before segregated audiences. Few, if any, Black leaders were willing to subject themselves and others to segregated or discriminatory seating practices. Moreover, when he became an ordained minister in the Congregational Church in 1839, Ward presided primarily over all-white congregations. Black people could not understand why he had not chosen to preach to Black congregants. Perhaps Ward thought that he could have the biggest impact by speaking to those who needed to hear about equality the most, or perhaps he needed a congregation that could financially support him and his family. Regardless, his actions were not always typical in the abolitionist community, and while many Black leaders appreciated Ward’s activism, they sometimes questioned his methods.

By 1839, the abolitionist Joshua Leavitt had appointed Ward as a lecturer on the American Anti-Slavery Society circuit. Ward proved to be a dynamic speaker; few who heard his speeches ever forgot them. Depending on his mood, he could be charming, funny, and charismatic—or cutting, cranky, and impatient. One fellow abolitionist and writer, William J. Wilson, expressed concern that Ward did not always exhibit “proper command over his inner self.”

In 1851, Ward went to Syracuse, N.Y., after lecturing around the country. Almost instantly, he found himself in trouble. A fugitive named Henry “Jerry” Williams had been captured and was going to be sent back to his enslavers in Missouri. Ward, Jermain Loguen, and Gerrit Smith—all leading abolitionists in the area—set out to free Williams by force. Armed with a battering ram, a group of Black and white abolitionists stormed the jail in which he was held. Although they succeeded in rescuing Williams and eventually got him to Canada, the effort came at the price of their own safety. After the rescue, Ward left for Canada as well. Although he didn’t know it at the time, he would never return to the United States.

In Canada, Ward still struggled to make a living and continued to advocate for enslaved and free Black people. In 1853, he helped Mary Ann Shadd Cary create the Provincial Freeman, an abolitionist newspaper that was the first to have a Black woman as its founder and editor. He also started and edited several other newspapers and traveled to England to deliver speeches on the anti-slavery lecture circuit. In 1855, Ward wrote about his life in Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro: His Anti-Slavery Labours in the United States, Canada, and England. As the title suggests, Ward was a radical who often felt without a home. This sense of homelessness is a theme that many Black leaders have expressed.

In my own work, I write about how many Black abolitionists faced two options during the antebellum period: They could either stay in America and fight the good fight, or they could leave. Ward saw leaving as his best option. He was not alone in this: Frederick Douglass, Alexander Crummell, Martin Delany, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, William Wells Brown, and William and Ellen Craft all left America as well. Most returned eventually, but Ward would never come back.

Once he settled in Canada, Ward became convinced that the country could be a “home for black men,” but he battled anti-Blackness there, too. He and his family experienced discrimination in hotels, schools, and other social spaces. Ward opined that “Canadian Negro hate is incomparably meaner than the Yankee article” and that poor people in Canada were often pitted against one another. He also saw racism as a major export of the United States, one that had contaminated race relations in other countries that were supposed to be safe havens for Black people. Many Black people had considered making their home in the United Kingdom, Liberia, or Haiti; Ward also considered Trinidad at one point, before finally settling on Jamaica.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Ward’s interest in the island was partly due to his activism with the free-produce movement, which sought to boycott goods produced by slave labor. His choice of Jamaica had little to do with its proximity to the United States; Ward had long since denounced the country and refused to see himself as American. But he was convinced that Jamaica could offer him what he wanted: stability, a sense of belonging, and equality. Slavery had been abolished in the British West Indies in 1834. Jamaica was also experiencing an acute labor shortage in its post-emancipation society, and Ward was offered 50 acres and a chance for change. He took it.

Unfortunately, Ward’s final years were a deep disappointment. He had left his wife and family in Canada with nothing. For three years they struggled to settle his debts and provide for themselves. Ward never went back to Canada and never gave his family money to survive, and it wasn’t until 1858 that they finally joined him. His time in Jamaica was not exactly peaceful, either: The island faced smallpox and cholera outbreaks and was in the midst of a drought. Economic and political tensions were high and led to unrest. In 1865, Ward witnessed the Morant Bay Rebellion, a large and violent protest against the widespread poverty and injustice on the island. Yet Ward disapproved of the rebellion and, shockingly, sided with the oppressors. He was not in touch or in tune with the needs of the people. Shortly after the rebellion, Ward died, exactly when and of what cause is unknown. He was in his early 50s.

The story of Ward’s life is replete with gaps and mysteries, and yet despite this, Blackett has produced a masterful biography. He has managed, working with many fragments, to piece together a picture of Ward’s activism and the admiration many people had for him. This in itself is no small feat. But to add to the challenges of writing about Ward, he was clearly a complicated and contradictory figure. His was an inspiring and yet sometimes difficult story. Ward’s struggles to find freedom, equality, peace, and belonging are still shared by many African Americans today.

Given the complexities of Ward’s life, Blackett does not leave the reader with many takeaways. But a “moral of the story” is not required here: Sometimes, the act of recovery is the greatest feat. Blackett’s biography is the portrait of a man who was flawed and who, at times, lacked the empathy to understand the needs of others, particularly in Jamaica during the Morant Bay Rebellion. In the end, Ward was neither a hero nor a villain. He was not a prominent political figure or a prophet. He lived a life of hardship; the life of the activist can take its toll and is rarely profitable. Free Black Americans like Ward did not face the horrors of slavery, but they were not liberated either. Ward fled for freedom, and even when he found a taste of it, he never found a real home. Perhaps true liberation is dictated by our sense of belonging—and for many Black people in the United States, that work remains ongoing.