The Invention of a Neighborhood

In 1977, a staff writer for The New Yorker named Jervis Anderson journeyed to Dean Street in Brooklyn, to the neighborhood now known as Boerum Hill, to interview the people who lived there. His article in the November 14th issue, titled “The Making of Boerum Hill,” portrayed the place as a microcosm of “one of the remarkable urban developments in recent times—the brownstone-renovation movement.” What drew Anderson to Boerum Hill isn’t certain. It’s possible he’d lived there when he first moved to the city from Jamaica, in 1958, to study at N.Y.U. In an autobiographical essay from 1966, he wrote, “In those early days, New York was to me Washington Square, the A train, and Brooklyn.”

What seems to have fascinated Anderson about Boerum Hill was the tenuousness of the neighborhood’s creation. “The name had been coined so recently, and by such a small number of the residents, that people who had been living in the area all their lives had never heard of Boerum Hill and hadn’t the slightest idea where it was,” Anderson writes. Initially, he explains, the campaign to establish the neighborhood, undertaken in order to protect dilapidated row houses from being condemned and demolished, “faltered in the face of a firm conviction that Boerum Hill existed only in the heads of the people who had thought it up.”

Boerum Hill was thought up in my lifetime, by people I knew. Anderson’s account of them is prescient. It reveals a white middle-class population not only dislodging a poor and diverse one but defining them out of the picture. Yet few seemed aware that they were doing anything wrong.

The blocks that became Boerum Hill were ringed, mostly, by older and more clearly defined precincts, like the traditionally posh Brooklyn Heights, the Italian-immigrant enclave Carroll Gardens, and Park Slope and Fort Greene, shaped by long-standing Irish and Black homeownership, respectively. None of these places were simple. Their fortunes rose and fell with changes typical of urban life in the postwar twentieth century—white flight, and redlining by banks that preferred “urban renewal” projects and deals with developers to the renovation of old buildings. But those had been recognized neighborhoods to begin with.

The new Boerum Hill was something less, or more. Scooped out of what was loosely known as North Gowanus, it was bounded on the north by downtown Brooklyn, a district of commerce and civic institutions, and on the south by two large housing projects, built in 1949 and 1966, and by the famously polluted industrial Gowanus Canal. In the early nineteen-sixties, when the brownstoners Anderson interviewed first moved there, the blocks of Dean Street, Pacific Street, and Bergen Street, now known for the beauty of their restoration—or for their scandalous multimillion-dollar listings—were at risk of wholesale demolition. Some buildings were vacant and crumbling; others were rooming houses filled with men, many of them retired dockworkers, or they were home to Black or Puerto Rican or Dominican families. A community of Native Americans from Canada and upstate New York, Mohawks who’d come to build skyscrapers, had also lived in the area, and their traces were still in evidence.

The zone was more a crossroads than a neighborhood. In a process now familiar, it was transformed, not by real-estate speculation—at the start, bankers and developers wanted no part of these buildings—but by the arrival of white artists and idealistic leftists who valorized integration.

I grew up on Dean Street. Some of Jervis Anderson’s subjects were parents of the children I ran with on the block; he might have passed us on his way up the stoop of a brownstone. The New Yorker was a common token among the aspirant middle class in the neighborhood. I learned to leaf through it backward, for the cartoons and for Pauline Kael. Yet I missed Anderson’s piece—perhaps that issue wasn’t one that was left out on the coffee table. When I discovered it, four years ago, I felt not only that I’d tunnelled through time to 1977 but that it offered something I’d long been denied. I’d spent years trying to conjugate the divisions I detected, as a child, among the white adults in my neighborhood. They’d chosen sides, at some point, over minute differences in attitude concerning their presence in Boerum Hill, and then covered the disagreement in silence. Here they were, talking.

I’d stumbled across a companion I hadn’t known to wish for—yet an elusive one. Anderson’s presence is sublimated, as was typical of the style of The New Yorker under William Shawn’s editorship, and typical, too, of Anderson’s own style: self-effacing, to an unusual degree.

There had been Black staffers at The New Yorker before Anderson. Charlayne Hunter-Gault, who with her classmate Hamilton Holmes broke the color line at the University of Georgia, did the same for the magazine’s writing staff when she was elevated from assistant to staff writer, in 1964. Dorothy Dean, whose fabulous, tragic life is portrayed in Hilton Als’s book “The Women,” worked in the fact-checking department in the same period. Yet Anderson, from the time of his hiring, in 1968, until the arrival of Jamaica Kincaid, in 1976, was the lone Black staff writer at the magazine. He wrote pieces on Alex Haley and Ralph Ellison, and a four-part series about Harlem, later collected as “This Was Harlem,” by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Anderson also wrote biographies of the civil-rights leader A. Philip Randolph and of Randolph’s extroverted lieutenant Bayard Rustin, an early mentor of Anderson’s.

Unlike Rustin, and unlike his hero James Baldwin, Anderson was soft-spoken. Few staffers who recalled him to me failed to mention his reserve. “He was a solitary guy,” Ian Frazier said. Of their conversations in the hall, Frazier told me, “Mostly these were about Shawn not running our pieces.” Jamaica Kincaid, who worked alongside Frazier—known as Sandy—as a writer for the Talk of the Town, shared a story about how Anderson had once given her a kiss as he passed her in the hallway. “I immediately ran to Sandy’s office,” she said. “I told him what had just happened and we laughed ourselves silly because Jervis was so mild-mannered, not seemingly vulnerable to such passionate outbursts. The kiss was most welcomed by me because he was attractive and brilliant.” Anderson was a democratic socialist, according to the staff writer Hendrik Hertzberg. The two men bonded in the magazine’s offices over politics, and Hertzberg suggested to me that Anderson’s deeper commitments may have been outside The New Yorker: “The Irving Howe crowd, the whole Dissent masthead, those were Jervis’s real friends.”

Nowadays, the term “gentrification” has become as familiar, and as blandly elastic, as “Kafkaesque” or “fascism.” The word doesn’t appear in Anderson’s article. (It doesn’t seem to have appeared in The New Yorker until November, 1982, in a piece about shopping uptown: those who consider Columbus Avenue a “style ghetto,” readers are told, will be pleased to find that “gentrification has brought a host of often admirable and attractive new boutiques.”) The word already existed, though, coined in 1964 by the German-born British sociologist Ruth Glass.

As it happens, the term “Boerum Hill” was coined that same year. At the time, it named an audacious promise, or a bluff. The name was created by an author of nonfiction named Helen Buckler, who had moved to Dean Street in 1962. It was popularized by, among others, another author, a novelist and journalist named L. J. Davis. Anderson interviewed them both. In both cases, I knew their houses from the inside.

Like “Boerum Hill” and “gentrification,” I was born in 1964. In that year, my parents lived in an illegal loft on West Broadway, where my father had a painting studio. We came to Dean Street in 1968.

My father was led there by a fellow-painter, Patricia Stegman. She and her husband, Robert Snyder, had purchased a building on the same block as Helen Buckler, and a second on Pacific Street, to serve as her studio. Bob and Pat Snyder, as they were known locally, were, according to Anderson, “the first middle-class home buyers to follow Miss Buckler.” The Snyders showed my parents a house, and, when my parents borrowed a down payment of three thousand dollars from my grandmother in Queens, Bob Snyder acted as the broker.

Snyder had taken up a real-estate license not out of any desire for a career but in the cause of keeping crumbling houses from being demolished; Realtors had turned their backs on these buildings. Hundred-year-old marble mantelpieces weren’t then a consensus taste. Among people who could afford to choose, many preferred modern buildings, often in the suburbs. It was Buckler who had suggested to the couple that they begin showing the houses. As the conjurer of the neighborhood’s existence, Buckler was the Wizard of Oz. The Snyders were Dorothy and her companions—the Wizard’s emissaries.

The house I grew up in was across from the Snyders, and five doors down from Helen Buckler. With the exception of a handful of children on the block—my friends Karl Rusnak and Lynn and Aaron Nottage, and the Snyders’ son, Adam—these adults were the first people I knew outside my home. One Saturday morning when I was ten, old enough to walk alone as far as the post office on Atlantic Avenue, I was sent to Helen Buckler’s parlor to take up my first employment, as her gofer. In that capacity, I walked Miss Buckler’s many handwritten letters to the post office, emptied her garbage cans, and changed her cat’s litter. She must have been eighty by then.

Before Brooklyn, Buckler had lived in Manhattan, and worked as a secretary and editorial writer at The Nation, and as an advertising copywriter at J. Walter Thompson. In her parlor, I’d sneak looks at the papers on her roll-top writing desk, trying to understand a world of Wasp provenance and taste that was to me utterly mysterious. As a child, I collected postcards. She gave me a set of old deckle-edged black-and-white postcards of a riverside hamlet in Hampshire, England, called Buckler’s Hard, to which, I understood, she traced her family origins. She seemed vaguely famous to me, as a revered elder of the Brooklyn Friends Meeting; Quaker families from all over Brooklyn took turns, Sunday mornings, driving her to the Meeting House on Schermerhorn Street.

Buckler, known to her friends and correspondents as Bobbie, was tiny, opinionated, and odd. She was nearly blind. In the sixties, she’d suffered both a hip infection and a bad fall, which was recounted to me by my mother: slipping in her bathroom, Helen had grabbed at a towel rack, which had snapped in two and pierced her ribs as she fell. The result, after a long recovery, was a spinal deformation that required her to walk with a cane; I’m ashamed of the horror this inspired in me. I didn’t want to keep visiting Miss Buckler’s well-appointed parlor, let alone the dank basement level, where the cat box was kept. I wanted to be out on the street, running amok.

“Miss Buckler’s friends were shocked to hear that she had bought a house in North Gowanus,” Jervis Anderson wrote. “To them, living in such an area was unthinkable. Nor was her confidence strengthened when some of the older residents told her that except for the rooming-house speculators she was the first ‘outside person’ in years to buy a house in the community. She herself could not help noticing how shabby the area was, that there were ‘gaps in some of the blocks, like teeth missing in a face,’ that ‘there were a lot of noisy people’ on the streets, who ‘were always fighting.’ But she reminded herself that those conditions could be found in many other sections of New York.” Anderson focusses on Buckler’s zeal for architectural detail—above all, for fireplaces. “I was lucky to find all the original etched-glass doors intact,” she told him. “I found the round over-mantle mirror gathering dust in the cellar.” She went on, “Since fireplaces are my passion, the chimney was the first thing I did. And now I have four good working fireplaces.”

Buckler set about the formation of a neighborhood association. “She called a meeting in her parlor,” Anderson wrote, “attended by seven or eight representatives of the old home-owning families.” In Buckler’s search, aided by the Long Island Historical Society, for an appropriate name, she almost settled on Sycamore Hill, but was perhaps unsatisfied by something so vague. “Looking over the names of the old farmers,” Anderson continued, “Miss Buckler found herself drawn to the name Boerum, which was already the name of a street in the neighborhood. The most famous member of that family was Simon Boerum, who, historians say, would have been one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence if he had not died in 1775.”

Anderson’s appetite for historical research suffuses his article. This likely helped him gain the trust of the brownstoners, whose eagerness for tracing lineages, between their restoration of the houses and the early history of the area, bordered on the fanatic. In 1964, it was unlikely that Helen Buckler or her enablers at the Historical Society would have troubled to notice that Boerum was the name of a slaveholding family. In 1977, Anderson quotes Franklin Burdge, Simon Boerum’s biographer: “Brooklyn at that time was a pleasant agricultural town of about 700 white and 200 black inhabitants, the latter almost all slaves.” Characteristically, Anderson leaves the implication for his reader to unpack.

Anderson reports that an early response to Buckler’s effort was a story in the Brooklyn section of the World-Telegram & Sun on March 26, 1964, titled “Rescue Operation on ‘Boerum Hill.’ ” As the newspaper explains, Buckler, “who likes old brownstones with a fireplace in every room, is spearheading a campaign to win public acceptance of a new name, ‘Boerum Hill’ for a run-down section of downtown Brooklyn.”

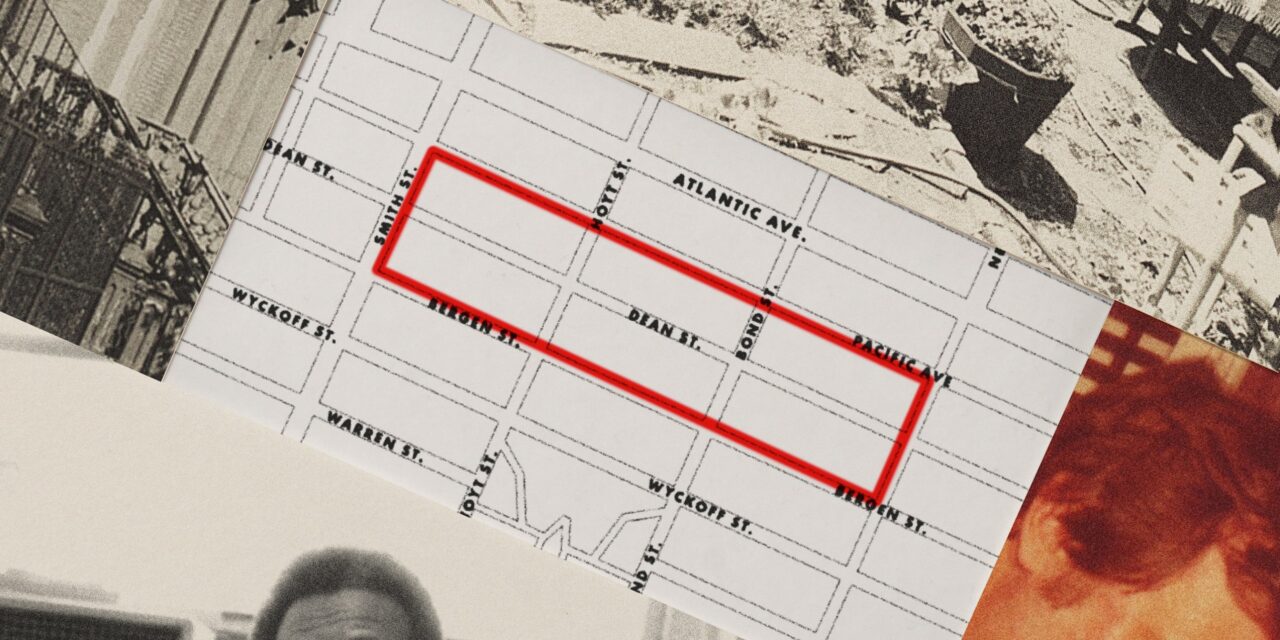

The World-Telegram & Sun story includes a map. It represents the propositional neighborhood as a solid black rectangle plopped into Brooklyn’s established terrain, with boundaries that would startle anyone who knows the current definition of Boerum Hill. Buckler, in carving out an island of safety from the objectionable terrain on either side, laid claim to only six city blocks: the boundaries ran along Bergen and Pacific Streets, and between Smith and Nevins. Atlantic Avenue, with its mess of storefronts—then mostly empty—was too enmeshed, perhaps, in the difficulties of “downtown Brooklyn.” These confines required the sacrifice of State Street, north of Atlantic, despite its several blocks of splendid, rescue-ready brownstones.

Even stranger, in avoidance of Wyckoff Gardens, the housing projects facing Wyckoff Street, not all of Bergen Street had been included in Boerum Hill’s first perimeter. Were this map to have been taken literally, the owners on Bergen’s south face, looking across the street, would have been met with a new neighborhood that had left them behind. The same weirdness would have pertained on Pacific Street. Buckler’s earliest draft of Boerum Hill was, essentially, a box around three blocks of Dean Street.

A “block association” defines a material fact. If you live on the block, you may choose to ignore its activities, yet you still live there. A “neighborhood association” describes an assertion in free space—civic space, historical space, racial space. The Boerum Hill Association believed that the houses on certain blocks held a meaning and a value that had become endangered by neglect—neglect by city and bank officials, but also by many of the people who occupied them.

Two years later, when the new name found its way into the Times, an updated map expanded the boundaries. Now Boerum Hill touched Schermerhorn Street to the north and Wyckoff to the south. In the 1966 story—“Brooklyn Renewal Is an Uphill Fight”—the bankers refusing to grant mortgages are given a chance to defend themselves. One, Frederick L. Kriete, an assistant vice-president of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank, called Boerum Hill an “odd case.” He puzzled over the brownstoners. “Generally, they’re cultivated, artistic people, with an appreciation for antiques and art—they’re a class all to themselves. I admire and appreciate their taste, but you wonder if the bank should get involved.”

Half a century later, the word “renewal” is widely understood as a euphemism for an intrinsically racist program of neighborhood demolition, favorable only to the financiers of freeways, shopping malls, and stadiums. The Times article quotes Bob Snyder, who recounts his difficulties with the banks. “They said we needed a sunken bathtub to get a loan,” Snyder said, “but we have a really wild Victorian bathtub.”

He added, “These are pretexts—they’re shielding the real reason, which is that the area is integrated.”

In 1967, a pamphlet appeared, limited to two hundred and forty copies, bearing the title “A History of Boerum Hill.” In seven pages of deliberately antique-looking Goudy Mediaeval font, it retails a saga beginning with the clearing of land north of Gowanus Cove by the Marechkawieck people, and “a minor land rush into the area” by Dutch tradesmen and farmers, including “Jacob Stoffelsen, the Dutch West India Company’s overseer of Negros.” Starting with colonial lore, the pamphlet centers Boerum Hill in the settling and development of Brooklyn, as if the name had always existed. It makes hasty work of the immediate past: “Although the neighborhood became steadily poorer in the years between the Second World War and 1962, in a strange way it was an architectural blessing.” It explains, “Boerum Hill was spared because of its poverty: simply, nobody could afford to ruin the fronts of their buildings. Following years of careful preservation, economic deterioration had the paradoxical effect of presenting to us, in the purest possible form, a perfectly preserved, mid-nineteenth-century neighborhood—a bit nibbled on the edges perhaps.”

L. J. Davis, the pamphlet’s author, bought a brownstone on Dean Street in 1965. A native of Idaho, Davis moved his young family to Brooklyn after completing a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford, in a cohort that included the novelist Stephen Dixon and the poet Robert Pinsky. Davis wrote four novels—published between 1968 and 1974—comedies portraying confused young men drowning in the squalor and diversity of the city. He is as much a master of what is now called “cringe” as Larry David or Nathan Fielder. “Like a comic actor with the crucial willingness to make himself look ridiculous, Davis sacrifices our good opinion for the sake of the art,” Evan Hughes, the author of “Literary Brooklyn,” writes. “He makes you think hard about whether this L. J. Davis guy is a bigot, and that means thinking hard about what bigotry is.”

Of these novels, “A Meaningful Life” is the fiercest. (I wrote the introduction for a 2009 reissue by New York Review Books Classics.) Hughes describes it as “the most lacerating portrait of the folly and shame that gentrification brings with it everywhere it goes.” Davis’s subject is the brownstoners: “They are the most house-proud people you could ever hope to meet. To start with, most of them were doing their own renovation, so they became obsessed.”

Davis wrote from within what he ironized. A house-proud renovator himself, and a working journalist, Davis was not only Boerum Hill’s needling existentialist but its early popularizer, one with a stake in the outcome, since he’d sunk his family’s future—its financial and emotional well-being—into the precarious situation. When, in 1969, New York magazine’s cover trumpeted “Brooklyn: The Sane Alternative,” Pete Hamill’s title essay made an overture to the borough’s revival; in the same issue, in a piece on brownstones, Davis advertised Boerum Hill houses to space-hungry Manhattanites—still available but going fast.

Davis bragged to Anderson about how he’d researched the first occupant of his house: “His name was Malachi Murray, and he was a stonemason. Murray lost the house in the financial crash of 1873.” Davis’s knack for history must have gratified the other brownstoners, whose zeal for marble mantelpieces and gas-fitted street lamps needed justification. The neighborhood’s entrancing past cried out from under the layers of lead paint; the effort of individuals to beautify their homes gained an ethical dimension when viewed as a collective mission of curation. The word “Victorian” was everywhere, knitting the area’s white future to its white past. The populations that had defined the postwar decades could be seen as a kind of placeholder, until the eleventh-hour rescue. Brownstoners even posed in their houses dressed in Victorian costumes, such as Park Slope’s Joy and Paul Wilkes, on the cover of their 1973 book, “You Don’t Have to Be Rich to Own a Brownstone.” Davis’s limited-edition 1967 pamphlet was reprinted in 1973 by Renaissance Properties—other brokers had by then stepped in, relieving Bob Snyder’s burden as a vigilante real-estate agent. If Helen Buckler was the first “author” of Boerum Hill, L. J. Davis was the second.

The scene had other novelist witnesses. Paula Fox moved to Dean Street in the late sixties, and got to know Davis. In an admiring 2009 review in The New York Review of Books, she compared him to Céline. Fox’s second novel, “Desperate Characters,” depicts their shared block in terms similar to Davis’s, as crime-ridden and garbage-strewn. When her book was filmed, partly in a brownstone on Pacific Street, in 1970, with Shirley MacLaine in the lead, Davis played a policeman investigating a break-in. The novel is celebrated, justly, for allegorizing urban fear as an existential condition: the risk of a break-in stands for an inchoate crisis in the life of a married couple who coexist in parallel silence. Yet readers on Dean Street at the time would have understood the risk literally. It was a commonplace, then, that every house would suffer regular break-ins until the ironwork defending the parlor windows and the basement entrance had been sufficiently strengthened, and the inviting fire escapes had been stripped away. And much early brownstoner energy was expended trying to rouse policemen to the task of pushing open-air prostitution and drug dealing beyond Helen Buckler’s boundary.

Rosellen Brown wasn’t a renovator, only a renter. She left Dean Street after three years, for New Hampshire, but her 1974 story collection, “Street Games,” depicts a cross-section of her block’s white, Hispanic, and Black inhabitants with precision and sympathy. In “Why I Quit the Gowanus Liberation Front,” Brown anatomizes the improbable blend of self-absolving idealisms that make the brownstoners, from this distance, so slippery to define. The scene is a neighborhood meeting, held in what Brown confirmed to me was a fictionalization of L. J. Davis’s parlor. “So I went to this meeting,” Brown writes. “It was in the house of a writer, a cat who gets his kicks out of having six working fireplaces.” She continues, “We had decided to have a multiethnic Street Fair complete with police barricades at both ends of the block to close it off even to the rest of George Street, thus indicating true inner-block solidarity (as opposed to intra-block, which comes later). We would find a cause to use the money for at our second meeting, when we could fight about how many people could relate to flower boxes, how many to gas lamps.”

L. J. Davis’s elder son, Jeremy, was one of my best friends during my high-school years. I spent many days and nights in their home. Their family included L.J.’s wife, a younger son, and two adopted daughters, who were Black.

I was fascinated with L.J., for his working writer’s office, for his collection of books and LPs so different from that of my parents, for his weird anecdotes and clench-jawed speaking style, full of invisible punctuation marks and eyebrow-arched pauses to allow implications to sink in. L.J. would, if we pleaded, cook us eggs Benedict, a dish I’d never heard of before. He took me to a matinée of “Sweeney Todd,” with Len Cariou—the first time I’d entered a Broadway auditorium. The only theatre I’d seen at that point had been enacted by giant puppets at antiwar protests.

By the time I was a visitor to L.J.’s home, the brownstoners had split into enemy camps. One was made up of the hippies and commune dwellers (my parents were both) who opposed what was then called displacement and vilified speculators. Despite that special irony which torments the community-minded who move into poor neighborhoods—our presence made the area whiter, and therefore, from the city’s point of view, more worthy of investment and policing—my parents’ camp regarded those, including L.J., who acquired buildings in addition to their own homes as culpable.

In the opposing camp were the brownstoners who opened their parlors to one another in yearly house tours. Proud of what they’d accomplished, they regarded the decrease in street crime and the increase in trees and property values as obvious goods, and the hippies as political dreamers. I suspect that my mother, an outspoken radical, came into direct conflict with L.J. She died before I befriended him.

It’s worth noting that local preservationists, in the sixties and early seventies, fought and won underdog battles against the forces of predatory urban renewal. Their defense of the houses equated, in the beginning, to protection for anyone living in the area, white or otherwise. “Boerum Hill Building Gets Temporary Lease on Life,” reads a headline in the April 20, 1967, edition of the Times: “A group of young property owners pushing baby carriages and carrying signs succeeded yesterday in temporarily preventing the city from razing a town house.” The story centers on the Snyders: “ ‘He’s a veteran picket. He helped save 434 State Street,’ said Mrs. Robert T. Snyder, pointing to her 13-month-old son Adam.” It goes on, “The structure, between Hoyt and Smith Streets, in a historic but deteriorated section of the borough, was to be torn down by helmeted wreckers sent by the Department of Real Estate. The building has been empty for two years and the Department of Buildings said it was a fire hazard and a gathering place for undesirables.”

A year earlier, the Times had written, “In a sense the battle of Boerum Hill epitomizes in miniature the nationwide tug-of-war between two principal schools of urban-renewal thought. Ranged on one side are those like the Brooklyn bankers, who envision renewal in the broad terms of clearance and complete rebuilding, even if it means sacrificing some sound old buildings. And on the other side are those, like Jane Jacobs, the author and caustic critic of many city planners, who see vitality even in slums.”

Jacobs, the author of “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” is a name usually linked with that of her nemesis, New York City’s unelected, power-mad city planner Robert Moses. Though by this time he’d been impugned as a bully, and his power had waned, the Moses-inspired Cross-Brooklyn Expressway attracted passionate opposition by Brooklyn civic groups as late as 1969. The David and Goliath struggle felt immediate, not theoretical.

The moral calculus lent righteousness to the brownstoners’ preservationist stance. Yet a tone had crept in, that of an élitist cult. The brownstoners seemed oblivious to the intimations lurking in materials such as an announcement in the “Community Forum” column of The Phoenix, Boerum Hill’s new local paper, advertising an insurance company’s offering. “The Brownstone Package Policy was not designed to offer coverage to everybody with a bit of cracked brown sandstone on any old city house,” the policy’s originator explained. “We’re not really insuring houses, we’re insuring homeowners of brownstones. . . . We will not consider slumlords or other ‘high-risk’ people.”

I’ve tried to picture Jervis Anderson sitting patiently in the brownstoners’ parlors, recording their declarations. “This thing about renovating an old house sounds very esoteric,” Patricia Snyder told him. “But it often goes together with a commitment to living in an area that is mixed in every way.” She continued, “We have much more diversity than Cobble Hill or Brooklyn Heights. Everybody shouldn’t be the same.” L. J. Davis struck a similar note: “I myself don’t need to live around people who all look like me. If I wanted to do that, I would not have come to New York City. I would have stayed in Boise, Idaho, where everybody looks just like me.”

It had seemed unlikely at first, in the teeth of the banks’ opposition and the indifference of the city officials: the brownstoners’ triumph. Yet here it was. In bringing the cultural gravitas of The New Yorker into the scene, Anderson had become a third “author” of Boerum Hill—the one who could ratify both Helen Buckler’s dream and L. J. Davis’s historical sleuthing. His article ends with the words “Boerum Hill is not a rumor anymore. It exists.” Declaring the brownstoners’ victory, Anderson also highlighted the contradictions that gnawed at the liberal renovators’ good intentions. His article predicts the heel turn the renovators were at that moment taking, from underdogs to overdogs, from “defenders” to “displacers.”

I visited William Harris, the founder of Renaissance Properties, who moved to the neighborhood in 1970, and asked him to describe the impact of Anderson’s reporting at the time. “The article was supposed to be a two-part piece, you know,” Harris told me. “And they said he stretched it out so that he could have all the free dinners that came along with the reporting.”

I was disconcerted by the tartness of the gossip. A newcomer by the standards of Buckler or Davis, Harris made up for lost time by opening Renaissance Properties in 1973 and, with a partner, snapping up eleven buildings on Atlantic Avenue in one swoop, for three thousand dollars apiece. When I mentioned the homes lived in by children I’d known growing up, or the once vacant storefront now housing Rucola, a fashionable restaurant, Harris routinely interjected, “I brokered that house.”

Buckler died in 1988, Davis in 2011. Harris remains a keeper of the flame. In his eighties, he still displays a fervor for the zone’s deep provenances. Thrilled by the recent rediscovery of a Revolutionary-era stone-lined well beneath the pavement near his house—possibly a remnant of the Continental Army’s Fort Box, captured by Redcoats during the Battle of Brooklyn—Harris helped contrive a plaque commemorating the well on the exterior wall of a dry cleaner.

As to Anderson’s article, Harris shrugged. “I wasn’t a subscriber,” he said. “I didn’t draw a tremendous amount from it.” He was struck, however, by how little attention Anderson gave to the Kahnawake and Akwesasne tribal people still living in the neighborhood then: “The Indians were here all over the place, and they’re only mentioned fleetingly, in about a line and a half.” The union hall frequented by Mohawk ironworkers was above the post office where I took Helen Buckler’s letters. At one point, their numbers were large enough that a Presbyterian church on Pacific Street gave services in their language. Hank’s Saloon, a late, lamented hipster bar, was during my childhood a Mohawk dive called the Doray Tavern.

Yet the emphasis on the Native Americans seems a substitution. The neighborhood’s Mohawk residents, made famous in a 1949 New Yorker piece by Joseph Mitchell, were scant by the late seventies. I recall widows in basement apartments. The local families whose children filled the public schools I attended, and the kids I played with on the street, weren’t Native American—they were Puerto Rican, Dominican, and Black. The urgency in the commemoration of various histories—architectural Victorianism, nineteenth-century middle-class urbanites, Washington’s soldiers, Mohawk ironworkers—corresponds precisely to the need to leave others unmentioned.

Mary Jane Melish, another Dean Street neighbor, was once a famous Communist. She and her husband, the Reverend William Howard Melish, were prominent in the American Party’s outreach to the Soviet Union. In the nineteen-fifties, a McCarthyist purge cost Melish his post at Brooklyn Heights’ Church of the Holy Trinity (now known as St. Ann & the Holy Trinity). In 1963, the Reverend Melish travelled to Ghana to deliver the memorial address at W. E. B. Du Bois’s funeral; several years earlier, when the American Friends Service Committee arranged for a teen-age Angela Davis to move from Birmingham, Alabama, to New York City to attend high school, she was placed in the Melishes’ home. “From the first moment I had heard about them, and the sacrifices they had made for the progressive movement, I had a great respect for both of them,” Davis writes in her autobiography. “Their suffering had simply made them stronger and more determined.”

Mary Jane Melish directed a youth center on the corner of Atlantic and Bond, part of the nineteenth-century settlement-house system that still survives across the five boroughs. Leonard Bernstein and Jerome Robbins stopped by, while working on “West Side Story,” to meet the street gangs that coexisted inside. I spent a lot of time at the center myself, since my father taught a woodworking class there. I barely recall Howard Melish, but the cherubic, bright-eyed Mary Jane was a regular presence in my mother’s circle, revered by our leftist friends for reasons I couldn’t have grasped at the time.

Jervis Anderson would have known of the Melishes’ radicalism, but he underplays it in his piece, even as he lets Mary Jane write his conclusion for him. She told Anderson, “The attitude of some of the renovators toward the poorer people—those who live in the run-down apartments or over storefronts—is very negative. The renovators are resented by these people, who feel that the community belongs to them as much as it belongs to the newcomers. They don’t like being looked down upon, they don’t like being excluded, and they don’t like being pushed out.” She goes on, “I believe that houses are things to be used. They are not museums. And it seems to me that to a lot of the renovators houses come first and people come later.”

Mary Jane Melish is gone, as is Robert Snyder, but Patricia Stegman, the painter who married and later divorced Snyder, and who directed her son’s stroller into the path of a wrecking crew, still lives on Dean Street. Her brownstone, the one with the “wild Victorian bathtub,” holds a special aura. The house, which had been in the possession of only one family, was bequeathed to the Salvation Army, which kept it sealed until the Snyders opted to buy it, in 1963. This represented a kind of immaculate conception. “Every doorknob is original,” Stegman told me this year. Not only had the property been conveyed intact, with details like front and back shutters, an ironwork patio, and a back-yard cistern, but it had required no eviction to take occupancy.

At ninety-three, Stegman no longer paints. The last exhibition listed on her Web site is the Gowanus Open Studios in 2016; it must be strange, for the first-generation brownstoners, to consider the voguishness of the place-name Gowanus, which the Boerum Hill Association was once so eager to distance itself from. I sat with Stegman and her son, Adam, in the same time-stopped parlor where, in 1970, she consented to pose, in Victorian dress, for a feature in the Times Magazine. Like Anderson, I brought a tape recorder, though interviewing her felt odd. Once, while babysitting me, Stegman had had to rush me to the emergency room with a spiking fever.

I handed her a copy of the 1977 article.

“They described me as tall, attractive, and mild-tempered. They don’t know me.”

“Two out of three ain’t bad,” Adam said.

Stegman remains angry at the bankers who redlined the neighborhood: “We went to millions of banks. They all said, ‘We’ve given a lot of mortgages in that neighborhood and we’re not going to give any more, because the neighborhood is no good now.’ ” As she paged through my tattered copy of the magazine, Anderson’s words rekindled wonder in Stegman, at the distance Dean Street has travelled, from rooming houses, demolition, and garbage-piled streets. The Snyders were central to the story: Bob’s real-estate license, the protests, the coverage they drew from the Times and elsewhere. “I feel I am responsible for making Brooklyn, not just Boerum Hill, a chic place to live,” she said. It seemed only a slight exaggeration.

The ethical line that Pat Stegman and Bob Snyder drew was firm: “People offered us many houses to buy. I would be rich if I had bought them. One man owned a whole flock of rooming houses. He offered them to me very cheaply. I said, ‘I don’t want to be a landlord of rooming houses.’ We would have had to evict or manage them.”

She added, “We had a chance to buy a house in Carroll Gardens. But I found the people there were bigoted. They said, ‘Oh, we’d be so thrilled to show to you and your husband, because we’d never sell to a Black person.’ Well, I had friends who were Black, and so I said, ‘They wouldn’t be comfortable coming here to visit me, right?’ ”

In 1993, I was shelving books at Moe’s, in Berkeley, where I worked as a clerk—at the time, Dean Street was far from my thoughts—when a blue-jacketed hardcover came into my hands: “Daniel Hale Williams: Negro Surgeon.” The author’s name was Helen Buckler. It took me an instant to recognize her in the photo on the back, above a citation from the National Council of Negro Women. “The surprises in the story were many,” Buckler wrote in the introduction. “It turned out to bear little resemblance to the usual Negro story. There are no slave cabins, no cotton fields, no city slums, no lynchings—only the slow crucifixion of the spirit.”

In March, I explored Helen Buckler’s papers, which are stored at the Wisconsin Historical Society. Among get-well cards and newspaper clippings on the founding of Boerum Hill are drafts of articles on racial equality, with titles like “Little Known Facts About Negroes” and “The Race Question: A Woman’s Problem.” In the latter, in which Buckler tackles the spectre of miscegenation panic head on, she writes, “Willingly or not, woman was made the crux of the matter. Whatever the economic and political forces surging and battling underneath the surface, the banner unfurled to lead the crusaders always carried the slogan: Defend White Womanhood!” Beneath dated language, her thinking is lucid.

The founders of Boerum Hill all avowed a desire to live in an integrated neighborhood. Many had participated in the cause of civil rights—even William Harris, who bought and sold so many houses. In his twenties, in Virginia, when Prince Edward County shut down its public schools to avoid forced integration, he’d volunteered as a teacher in a makeshift integrated school. How had these crusaders—against the “little boxes” of suburbia, against eminent domain, against blandly uniform lives—ended up on the wrong side of Mary Jane Melish’s formula of “houses come first and people come later”? Had some intoxicant in the solvent they’d used to strip paint from the old moldings led them astray? Or was there an original sin in Buckler’s drawing of a boundary around Boerum Hill in the first place?

By the time of Jervis Anderson’s piece, L. J. Davis had stopped writing boosterish articles. Brownstone advocacy was redundant. The craze was official. Davis’s fiction had never sold much—the manuscript of a fifth novel went into a drawer—and he refashioned himself as an investigative reporter, specializing in financial scandal. A 1979 Harper’s cover story, “The Money Vanishes,” dissected the Carter Administration official Bert Lance; Davis’s 1982 book, “Bad Money,” exposed the credit crisis.

L.J. was by then also done opening his parlor, either to the house tours or to meetings of the Gowanus Liberation Front. He’d become a curmudgeon, our local Mencken or Vonnegut. In his columns in The Phoenix, alongside sunny coverage of the annual Atlantic Antic street fair and the openings of new restaurants, L.J. fulminated about Erica Jong, H. P. Lovecraft, and the degeneration of written English. “Descartes was a lucky dog,” one column begins, explaining that “he did not live on a bus stop” and “was therefore spared the small agonies of citizenship at its rawest: drunken softball teams celebrating on his stoop at two in the morning, beer cans in his shrubbery.” Another starts, “I sometimes wonder if I’m a safe person for me to know.” Elsewhere, he refers to himself as “the Darth Vader of Dean Street.”

L.J.’s neighbors would have detected, in this arch tone, that he felt cornered by leftist voices. A 1980 column, written in tribute to Helen Buckler, resorts to bitter sarcasm. “It looks so easy,” he writes. “You take a declining neighborhood, move into it, fix up the premises, and encourage other, like-minded souls to do the same. Hey presto, a rejuvenated neighborhood or a gentrified one, take your pick.” The piece spirals into a rant: “Nor was it, as certain ageing hippies would have us believe, an act of dark and sinister cunning.” He continues, “There was still no neighborhood here, just a lot of desperate poor people crammed into structures built to contain a tenth of their number—and at night, the sound of children being beaten unmercifully. This was the earthly paradise we are now called upon to admire by people who, in those days, wouldn’t have lived here on a bet.” Then it turns horrible: “It is hard to see what could have been done, short of some sort of concentration camp.” Elsewhere, L.J. makes shrouded reference to “the Indian reservation.” He means the Gowanus Houses projects, the setting, fifteen years later, of Spike Lee’s “Clockers.”

Had L.J.—to use the phrase he would have chosen himself—“gone mad”? For me, he is an emblem of the complex intellect who, feeling a critique of his privilege, jumps calamitously the wrong way.

L. J. Davis wrecked his journalistic credibility with a single pratfall. In 1994, The New Republic sent him on assignment to Little Rock, Arkansas, to sleuth around the financial paper trail known as Whitewater. L.J. mistook an alcoholic blackout episode in his hotel room for a possible assault. The Wall Street Journal reported that pages had been torn from his research notebook. L.J. later said that they had only ripped—and the hotel bartender observed that he’d had perhaps six Martinis before ascending to his room—but it was too late. The Republican conspiracy machine relished the suggestion that a journalist researching the Clintons had been attacked, and read the incident into the Congressional Record; L.J. was ahead of his time yet again. Still, he wrote two books afterward: one on cable-television moguls, and a passion project on the history of electrification. In his final years, he was a garrulous daytime drinker. His neighbors would sometimes cross the street to avoid being subject to his monologues. I did this myself.

Jervis Anderson died in 1999 or 2000, sometime between Christmas and New Year’s Day. His body was found early in January, when neighbors noticed mail piling up. He’d retired from The New Yorker the year before, after thirty years, publishing little in the magazine toward the end. Known once for his formality and dignity, he’d become a figure of isolation, and there were rumors of solitary drinking. Unlike Joseph Mitchell, he didn’t gain a legend for his reluctance. He showed up until he didn’t, and then he died at home.

I’ve spent the past four years wishing I could speak with Anderson, wishing I could cajole him into telling me what he thought about the white people on Dean Street. More recently, I’ve sought out those who knew him, hoping they’d make him more legible. Hendrik Hertzberg’s Talk of the Town obituary describes Anderson as a “product of British colonialism and West Indian anticolonialism, leavened by Harlem and the Upper West Side.” I spoke with Anne Nelson, who became good friends with Anderson during her time in The New Yorker’s typing pool, before a career as an author and playwright. “Jervis didn’t express the anger of ‘I’m living with the descendants of my slaveowners,’ ” she told me. “He didn’t share that attitude. He was analyzing, he was reporting. His writing was about advancing African American civil rights, but doing so systematically.” Discussing his first years as a writer in New York, she said, “This could have put him in conflict with people who might assume he would be an ally. Here is Jervis, the stately Jamaican wearing a suit—out of step, and out of time.” In his 1966 autobiographical essay, which was published in the Teachers College Record, Anderson himself develops this image: “We had been colonials for a long time and had grown to be as chauvinistic about English taste and English tradition as the English themselves. The involuntary reverence that most West Indians feel for the English sensibility and the English way of life must—even now that the Empire has been liquidated—stand as one of the sweeter and more deadly triumphs of imperialism.” The tone, both wistful and remorseless, is that of a writer who allows the reader—and history—to be the judge. Perhaps it also accounts for Anderson’s capacity to occupy the role of The New Yorker’s sole Black staff writer for so long. His instantiation of a psychic position somewhere between the dominant culture and the point of view of the oppressed was his tool and his method, until—I’m speculating—this method collapsed on him.

At some stage, it occurred to me that I might be searching in the wrong place, or asking of Anderson something he shouldn’t have to deliver. If what I craved was to hear from a Black person who’d spent time in L. J. Davis’s house, I needed only to search out one of L.J.’s daughters.

When I spoke with Tina, the younger of the two, it was the first time in forty-odd years. We compared notes on the experience of growing up in a time and place where a vision was being propagated of integration as a mission accomplished. The lives of the children playing on Dean Street were supposed to be a victory lap. Tina called it “a bubble”—a thing destined to burst, a dream deferred.

“When I stepped out of that bubble, I saw things,” she said, explaining what happened when she started attending school in Manhattan. “It was scary. Things went haywire when I started meeting people from other neighborhoods. People realized I wasn’t a part of them, I wasn’t from their world. I’d get picked on. I started realizing I would have to act more Black. Like, what does that mean? Why can’t I do this right?”

I was a little surprised that the reckoning had waited until Tina left the neighborhood. I pointed out that the housing projects were just two blocks away.

Tina said simply, “I wasn’t allowed to go over there.”

She continued, “I love my dad. He was a strong man, who stood up for all of us. And who laughed.” Then she clarified his prohibition against her walking in the direction of the projects: “Dad was classist. If you had a different economic standard, he was, like, ‘You’re a Davis, and you don’t go over there.’ With me and my sister, it was: ‘You need to find a different class of people.’ ”

Tina didn’t need to explain further. There was a time when I’d had friends in the Wyckoff Gardens towers—grade-school kids, Black and Chinese and Puerto Rican and Dominican—whose birthday parties I attended, or whom I unself-consciously followed home. Then, as if a memo went out sometime in the mid-seventies, most of the children from Dean Street stopped going to the projects to play, if we ever had. We tried to stay in the bubble, to make integration work on our blocks alone. It couldn’t, of course.

The white people who arrived in that part of Brooklyn in the sixties and seventies saw divisions among themselves. In one home lived speculators willing to manage tenants—and to evict them. In another, Maoists lived communally and worked to overthrow the state. Elsewhere, everything in between: artists, eccentrics, families. The long lens of time blurs these distinctions, making us see the brownstoners instead as collectively deluded about their culpability. This remains the case even as historians of civic life have been slowly picking apart the notion that what we call “gentrification” is simple or predictable in its effects. (Some, like Bo McMillan, a researcher for the Redress Movement, suggest that the term has itself gradually become an obscuring fiction.) Jervis Anderson’s gift was to portray the brownstoners as I recall them: people trying, and largely failing, to grasp their place in history in real time. You and I may be doing the same now.

Not everyone who moved onto those blocks ran a youth center, like Mary Jane Melish, or taught carpentry there, like my father (who also gave art lessons at the Brooklyn House of Detention). Some merely wished to live in a place that was diverse and yet neither crime-ridden nor scheduled for demolition. They might ask now: was that wish a crime? I’ve come to see this quandary as historically specific. What if theirs was a generation who believed that their desire for a just society had been addressed by the civil-rights movement—in which many had played some part—more fully than was the case? For those trying to inhabit Helen Buckler’s dream, the two enormous housing projects were a truth hidden in plain sight. Boerum Hill, that invention, was a gated community bounded only by a concept. The concept didn’t stop anyone walking down the street, except when it did.

The projects sat a mere five hundred feet from Tina’s childhood home, as from mine. Yet the situation within them was, at best, not our concern. At worst, it was a daily emergency we were prohibited from giving a name. What happened there happened elsewhere. For, according to Miss Buckler’s boundary, it was elsewhere. The boundary was a recipe for cognitive dissonance, for a preëmptive turning aside, in favor of more solvable matters, like how to restore a ceiling’s crumbling plaster scrollwork. It wasn’t only Tina Davis, or L. J. Davis, who couldn’t square the circle, couldn’t do the moral or emotional math. Helen Buckler didn’t intend to drive us all mad, in drawing an invisible line down Bergen Street, but she did so nonetheless. ♦