The Crown, the Cabinet and the UK’s legacy of slavery

The story of the merchant whose descendants include the king and Britain’s finance minister offers more than a look at that nation’s slavery economy. It also reveals how the British system shaped slavery in America.

KINGSTON, Jamaica

The plantation known as Farm Pen once stretched across 760 acres of flat, fertile land not far from here.

The estate was owned in the late 18th century by a British banking family that included George Smith, a wealthy member of parliament who invested deeply in the slavery economy. In 1798, records show, 237 people were enslaved on Farm Pen and two nearby plantations.

Smith ran his business from afar. He never lived at Farm Pen and instead oversaw his interests here from a country estate just outside of London, more than 4,500 miles across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Smith family legacy is a remnant of a colonial empire built in part on slavery. It also directly connects two of Britain’s most powerful people today to that troubling past: Reuters found that Smith is a direct ancestor of both King Charles III and Jeremy Hunt, the country’s finance minister.

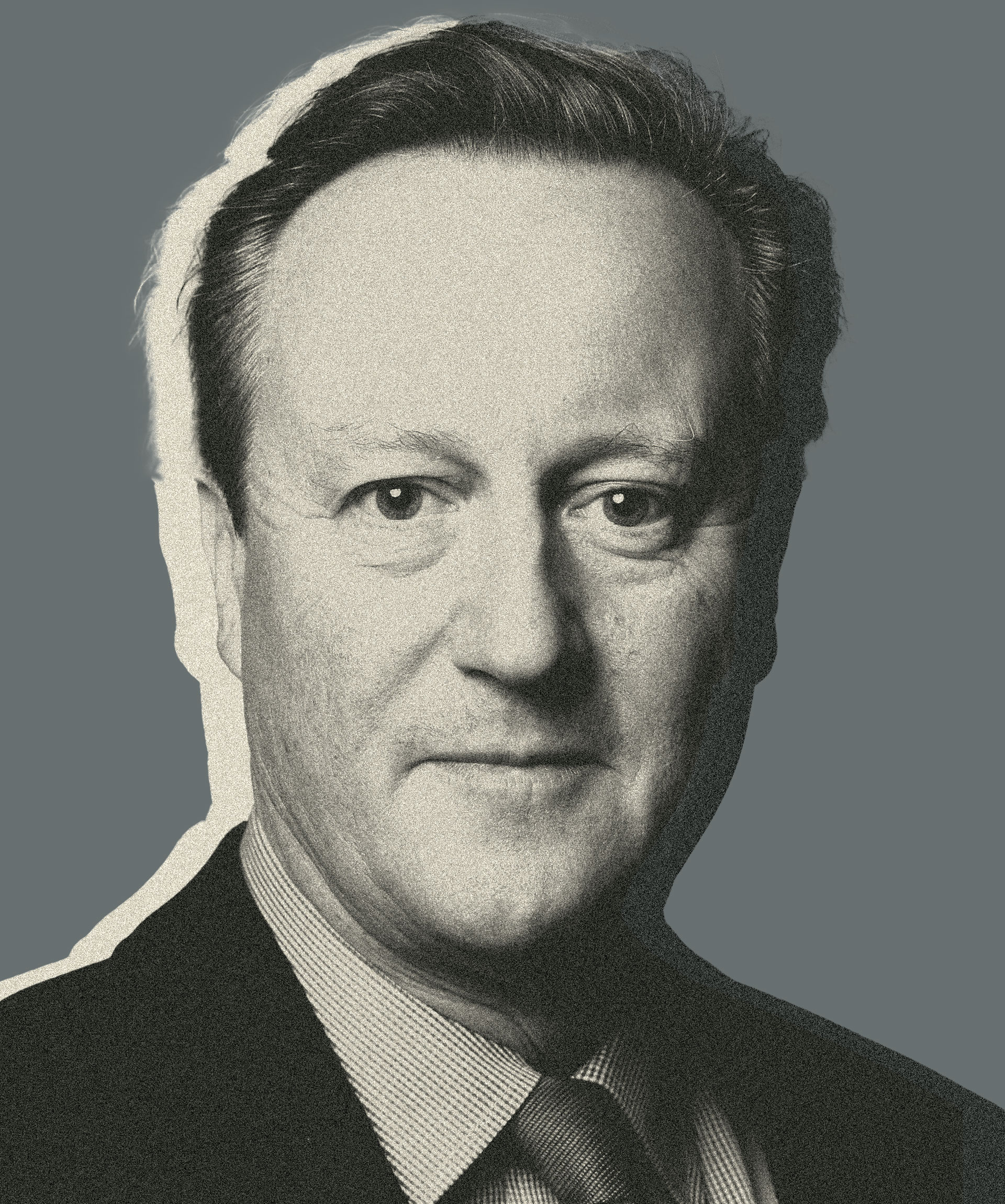

In examining the genealogies of some of the most notable British politicians and royals, Reuters found examples of contemporary elites whose direct ancestors participated in myriad aspects of the Transatlantic slavery economy. Among them: Hunt and three other sitting government ministers – including David Cameron, the former prime minister who joined the cabinet as foreign minister this month.

Previous reporting linked Cameron to an indirect slaveholding ancestor. Reuters found that Cameron is a direct lineal descendant of Alice Eliot, who owned a plantation in Antigua in the early 19th century where more than 200 people were enslaved. Eliot is Cameron’s great-great-great-great-great-great-grandmother.

Reuters also found that King George II, Cameron’s great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, was a financial investor and governor for the South Sea Company, which prospered greatly from the slavery trade during the 18th century.

Cameron did not comment to Reuters for this article. During an address as prime minister to Jamaica’s parliament in 2015, Cameron said he hoped that Britain and Jamaica “can move on from this painful legacy.”

The ancestral links of Hunt and Charles to George Smith, revealed by the Reuters analysis, tie the family of Britain’s new king to slaveholding right up to the nation’s abolition of the institution in the 1830s. Previous reporting has linked Charles III’s lineage to slaveholding in the 1700s.

Hunt did not comment on the Reuters findings. Through a long political career, Hunt has condemned racism and praised the contribution of Black Britons. He signed a pledge in 2020 that calls on Conservatives to raise awareness of racial prejudice.

Buckingham Palace referred Reuters to a passage of a speech by Charles last year to the Commonwealth leaders in Rwanda. “I cannot describe the depths of my personal sorrow at the suffering of so many, as I continue to deepen my own understanding of slavery’s enduring impact,” Charles said.

The king has also spoken in the past about “the appalling atrocity of slavery.”

The Palace said in April it is cooperating with an independent study exploring the relationship between the monarchy and the slavery trade, noting that Charles takes the issue “profoundly seriously.” That study comes as leaders in Jamaica and other Caribbean nations have called for reparations from Britain for slavery.

Today’s royal family itself has been jolted by questions of race. The family denied it was racist following comments in 2021 by Charles’ younger son, Prince Harry, and Harry’s wife, Meghan, the American daughter of a Black mother and white father. The two said they stepped down as working royals because they had not been supported by the royal household and indicated this was in part linked to Meghan’s Black ancestry. The couple declined to comment.

Because British involvement in slavery took place far from home, only recently have many white Britons begun to consider the deep influence their country had on slavery, and that slavery has had on their country. Less examined: how the British system of slavery shaped America’s.

As part of a series on slavery and America’s political elite, Reuters earlier this year reported that a fifth of U.S. congressmen, living presidents, Supreme Court justices and governors have direct ancestors who enslaved Black people.

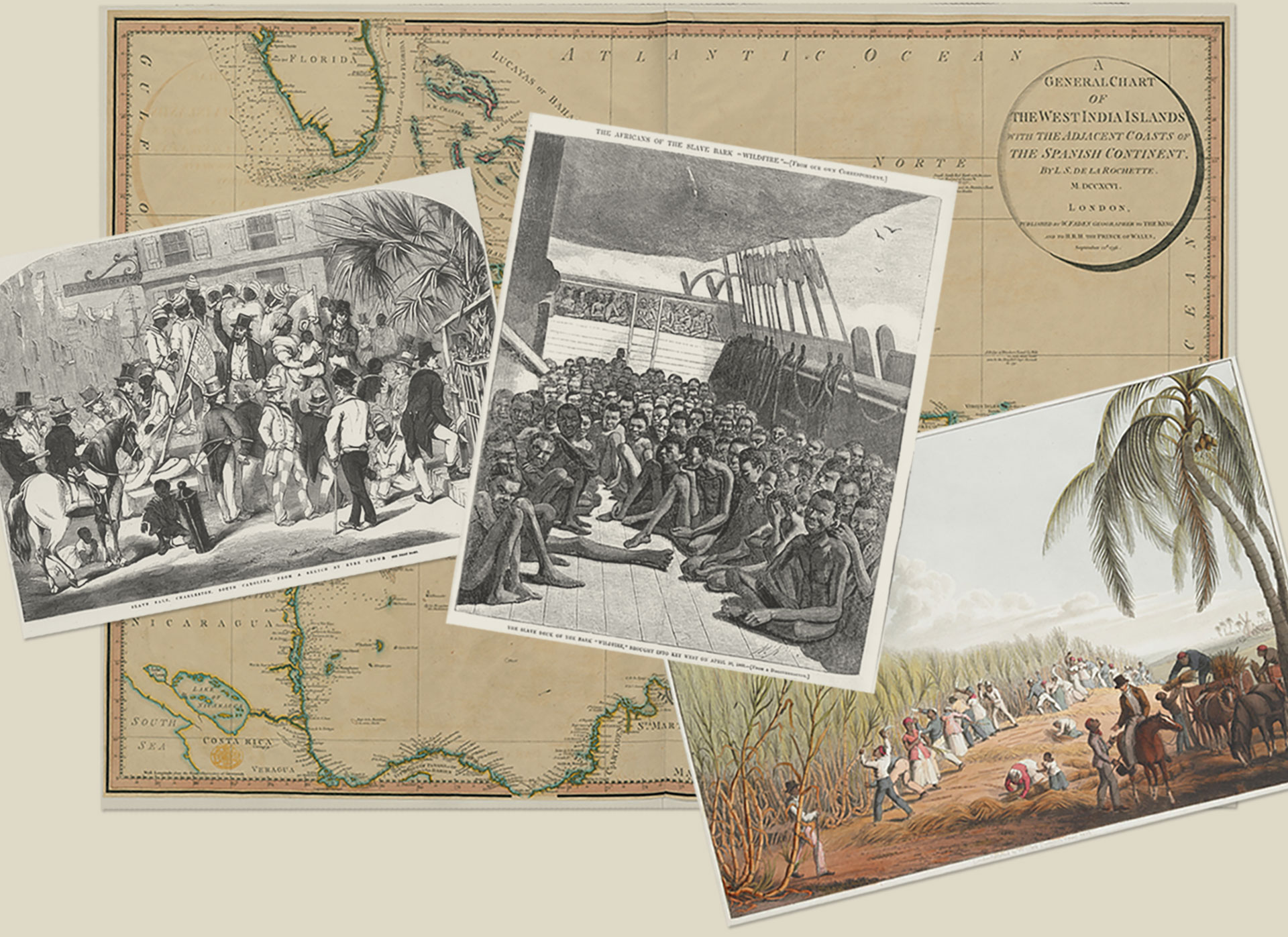

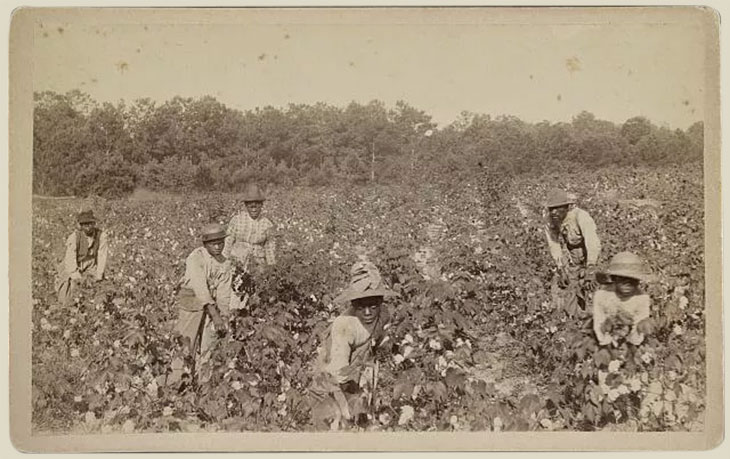

Britain dominated the development of slavery in North America and the Caribbean, trafficking millions of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean and governing colonies whose legal systems classified human beings as property. The British monarchy promoted the acquisition and expansion of colonies – including what became the American states of Georgia and Carolina – that relied on the labor of enslaved Africans. British ships delivered Black people to the shores of what would become the United States. From large houses of finance to individual investors, Britain invested in those ships, the plantations to which the enslaved were brought, and the crops produced by the backbreaking labor that followed.

Those connections continued even after America declared its independence from Britain in 1776. British banks backed large parts of the U.S. slavery economy, and British factories were the world’s largest customers for the cotton produced by plantations in southern U.S. states. American slaveholders also adopted some of the mechanisms of repression used by British enslavers in the Caribbean.

“The technology of slavery, the legal framework, and indeed the supply of people – the American colonies under British rule are no different from the British Caribbean. They’re part and parcel, obviously, of the same imperial system,” said Nick Draper, co-founder of a groundbreaking project at University College London that includes an online repository identifying slaveholders at the time Britain abolished the practice.

The story of George Smith, the ancestor of both King Charles and Hunt, illustrates many aspects of Britain’s role in a global slavery empire, and how that influenced what slavery became in America.

“Without Britain, the growth of slavery in America, the particular manifestation of it in cotton, just wouldn’t have happened,” said Trevor Burnard, a history professor and director of the Wilberforce Institute for the Study of Slavery and Emancipation at the University of Hull.

“To understand American slavery,” Burnard said, “you have to understand its connections with Britain.”

Investing in slavery

Smith was born in 1765, the son of a banker. The family was prominent. Its red brick Georgian mansion still stands outside the central English city of Nottingham, and the Smith crest can be seen in the stained glass windows of a medieval church at the city center.

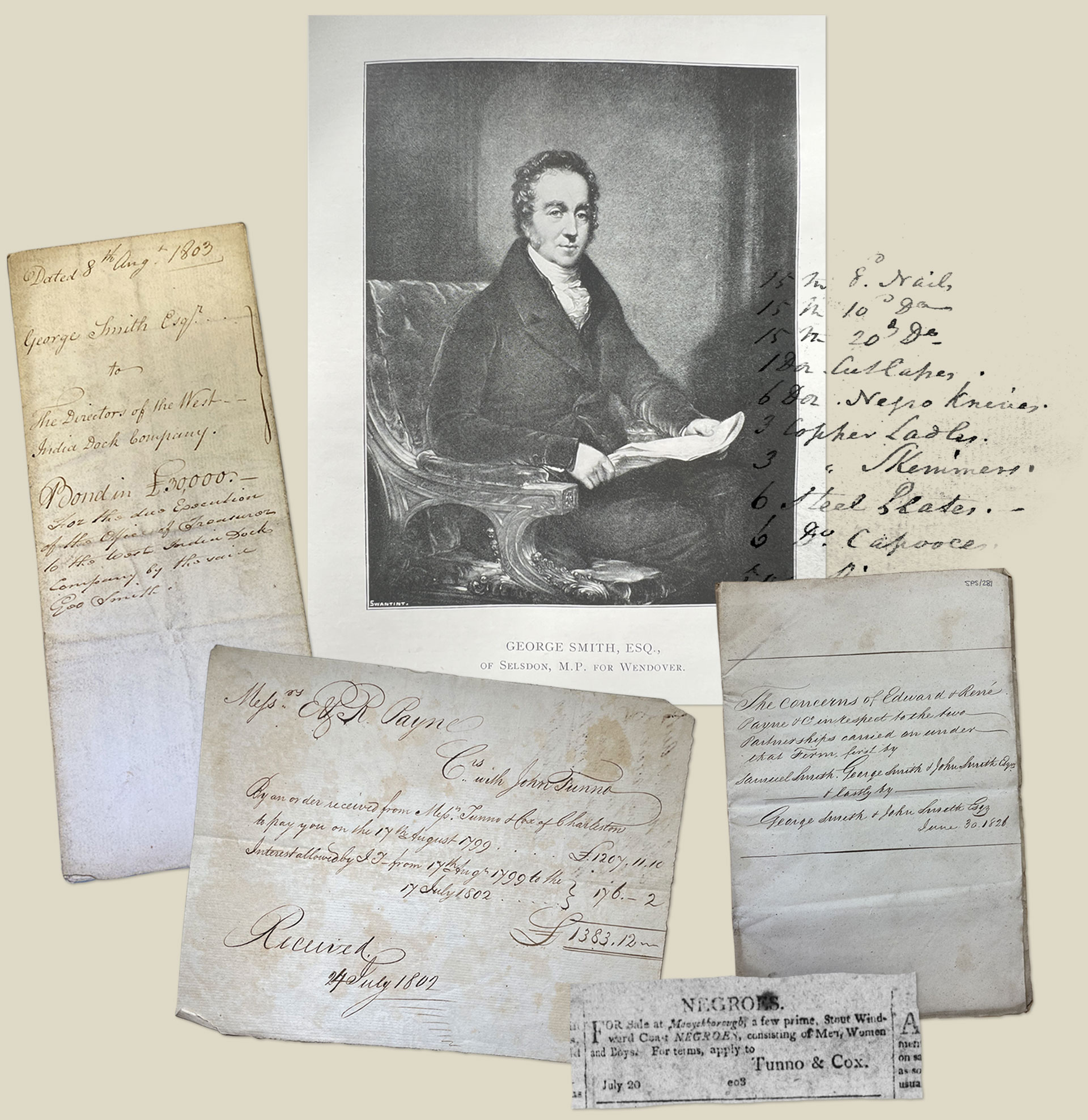

After completing his education, George Smith lived in London during his early 20s, and then bought into a West India merchant partnership called Edward and René Payne & Co in 1789. Such companies were at the heart of the British role in the global slavery economy, facilitating the flow of sugar, rum and coffee from the Caribbean to Britain’s big ports in London, Bristol and Liverpool.

Reuters examined more than 2,000 pages of letters, ledgers and invoices related to the Smith banking business. That included records of Payne & Co’s trade with Caribbean plantations and merchants. The records show that Payne & Co worked closely with slaveholders and traders, including some in the United States.

One 1802 invoice, for example, names a South Carolina merchant, John Tunno, as a client. Tunno’s firm placed advertisements in a Charleston newspaper offering for sale “Windward Coast Negroes” – enslaved African “men, women and boys,” the ad says, from the continent’s western coast.

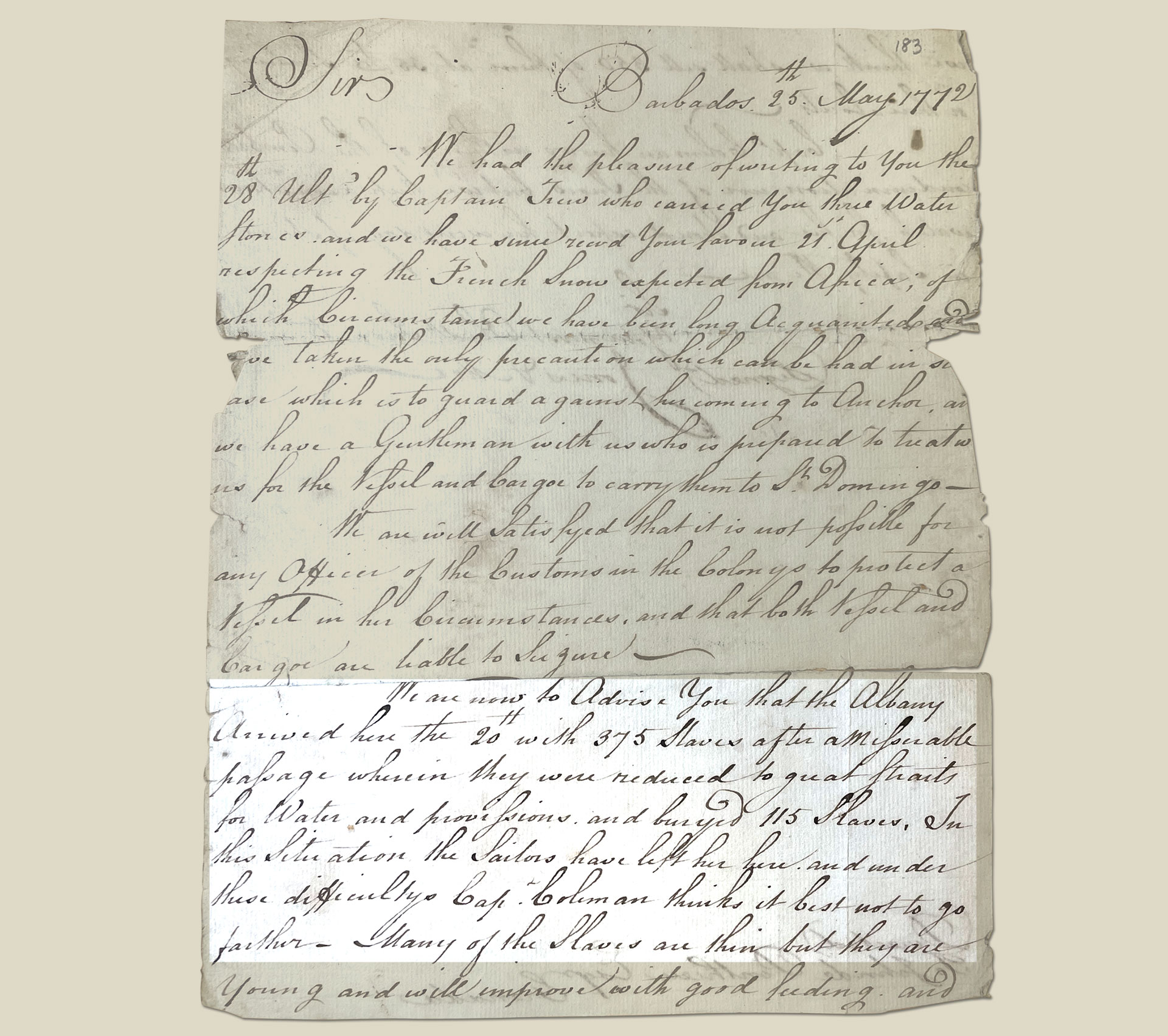

A 1772 Letter to

John de Ponthieu

“…with 375 slaves after a miserable passage wherein they were reduced to great straits for water and provisions and buryed (sic) 115 slaves …”

Edward Payne, founder of the firm, had also done business with slaveholder John de Ponthieu. A 1772 letter to de Ponthieu, written from Barbados by a man involved in the slavery trade, describes a “miserable passage” of a ship carrying 375 enslaved Africans. Water and provisions ran critically low and the crew “buryed (sic) 115 slaves” during the journey. It was standard practice at the time to throw the dead, and sometimes the sick, overboard.

The money to finance that trade came in part from British merchants taking fractional ownership of ships used to transport the enslaved. Capital also poured in from large firms such as the Company of Royal Adventurers of England Trading into Africa. In 1663, it was granted a monopoly by King Charles II for the British slavery trade. The grant enabled the company, later known as the Royal African Company, to buy people captured in Africa and ship them to Britain’s colonies.

John Montagu, a current-day earl and member of the House of Lords, is a direct descendant of Edward Montagu, an earl who was a founding investor of the Royal African Company, according to the firm’s charter. Edward Montagu also was president of a royal committee responsible for, among other things, expanding slavery in North American colonies and facilitating the flow of enslaved Africans.

Asked about that lineage, Montagu said in a statement to Reuters that “any feelings of pride in our ancestors should be, and will be, tempered by any knowledge of connections with slavery.”

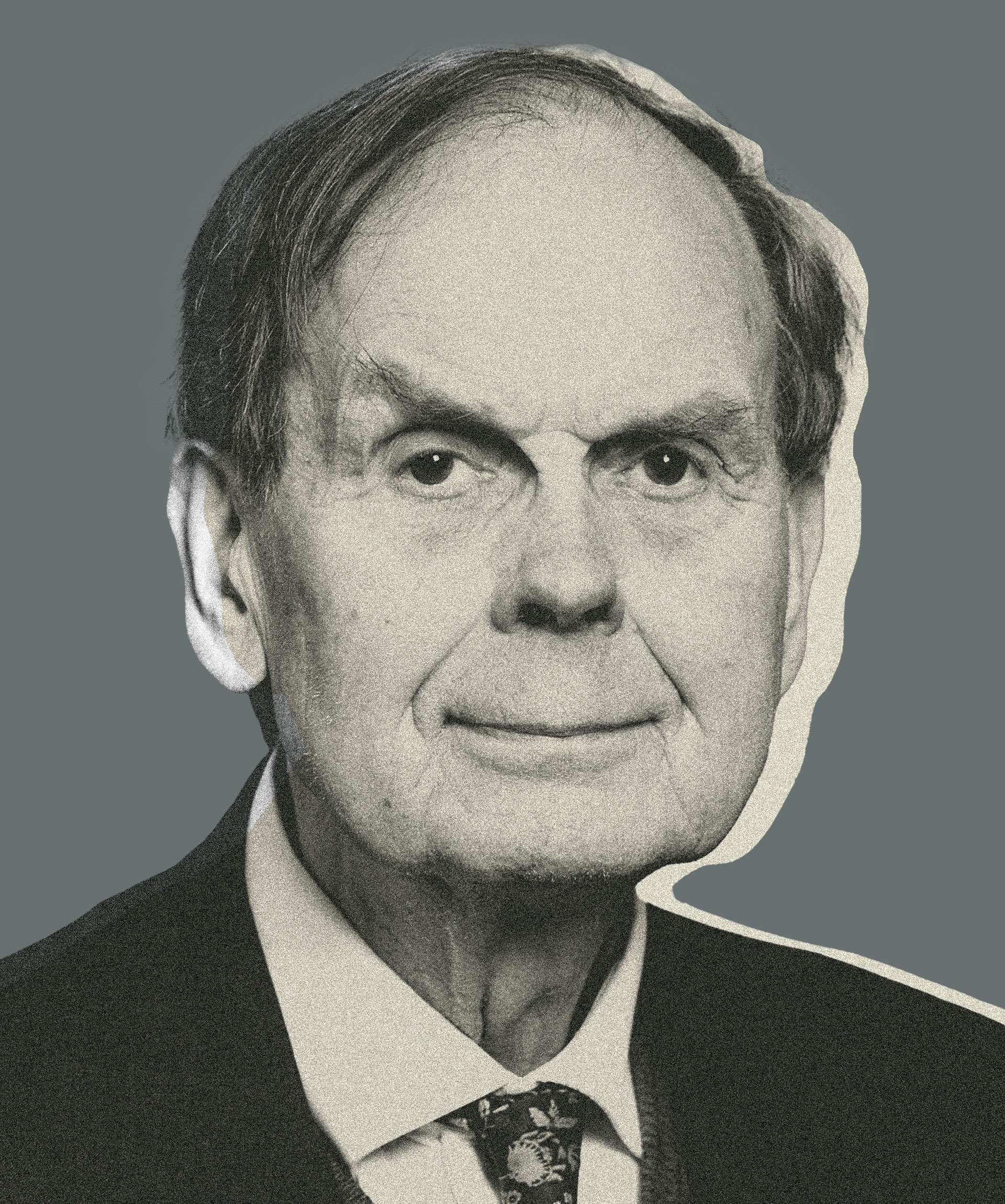

John Montagu

11th Earl of Sandwich, member of the House of Lords

DIRECT ANCESTOR Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich

RELATIONSHIP Great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandson of Edward Montagu

ROLE IN SLAVERY ECONOMY Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich, was a founding investor in the The Company of Royal Adventurers of England Trading into Africa, a company established to trade in enslaved Africans. He was also president of a royal committee responsible for, among other things, expanding slavery in North American colonies and facilitating the flow of enslaved Africans.

Many investors were aware of the details of what their money was financing, said Nicholas Radburn, a historian at Lancaster University and author of Traders in Men, a recent book that traces the evolution of the Transatlantic slavery trade.

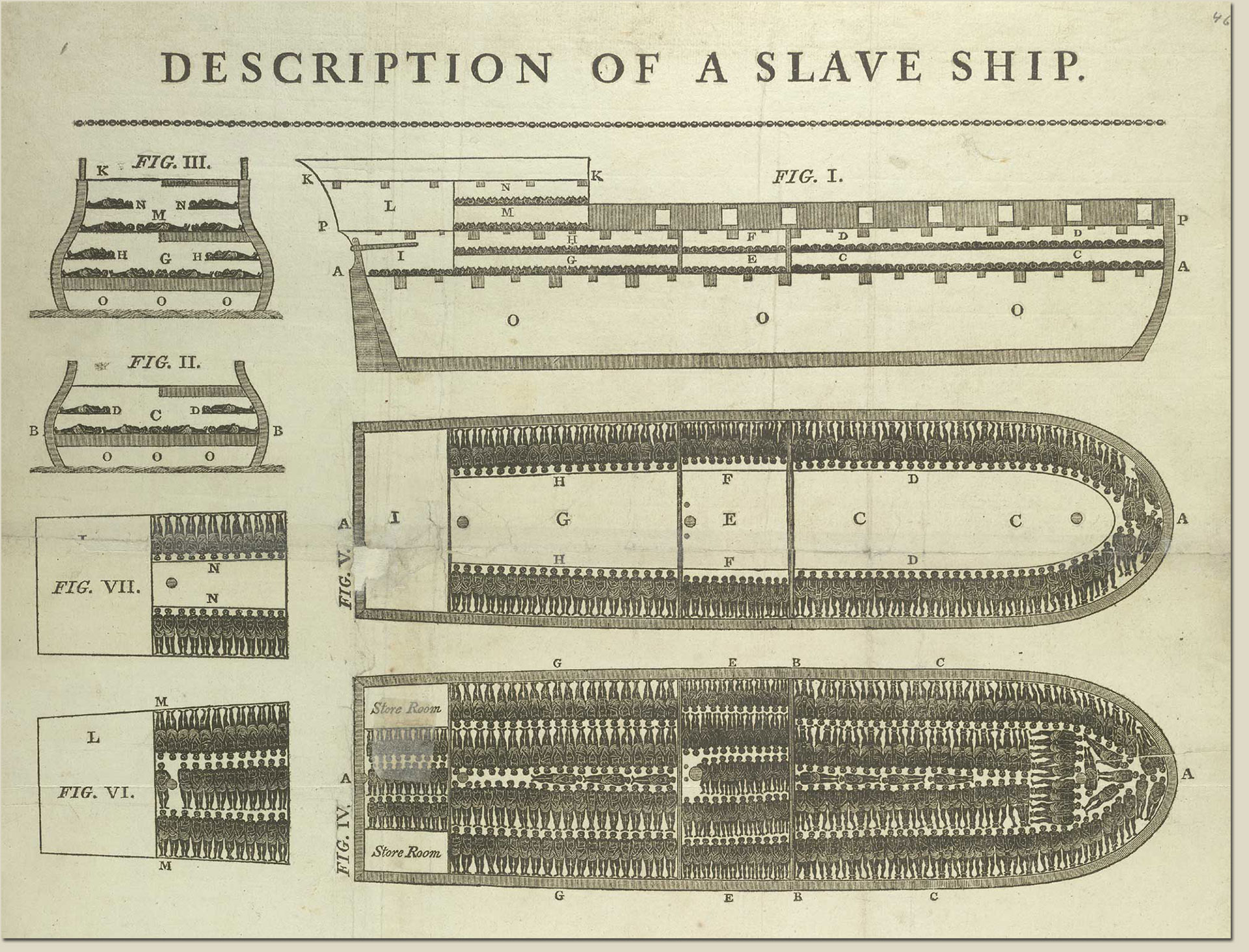

Outfitters of slaving ships, for instance, would often go aboard and immerse themselves in the grim details: “How many feet of chain do we need? How many shackles do we need? How much food do we need to put onboard? How many guards do we need? How many weapons? How long will this voyage be? How many people will die on it?” Radburn said. “These are the sort of macabre calculations that are inherent to the business of the slave trade.”

Diagram of the Brookes

The family business

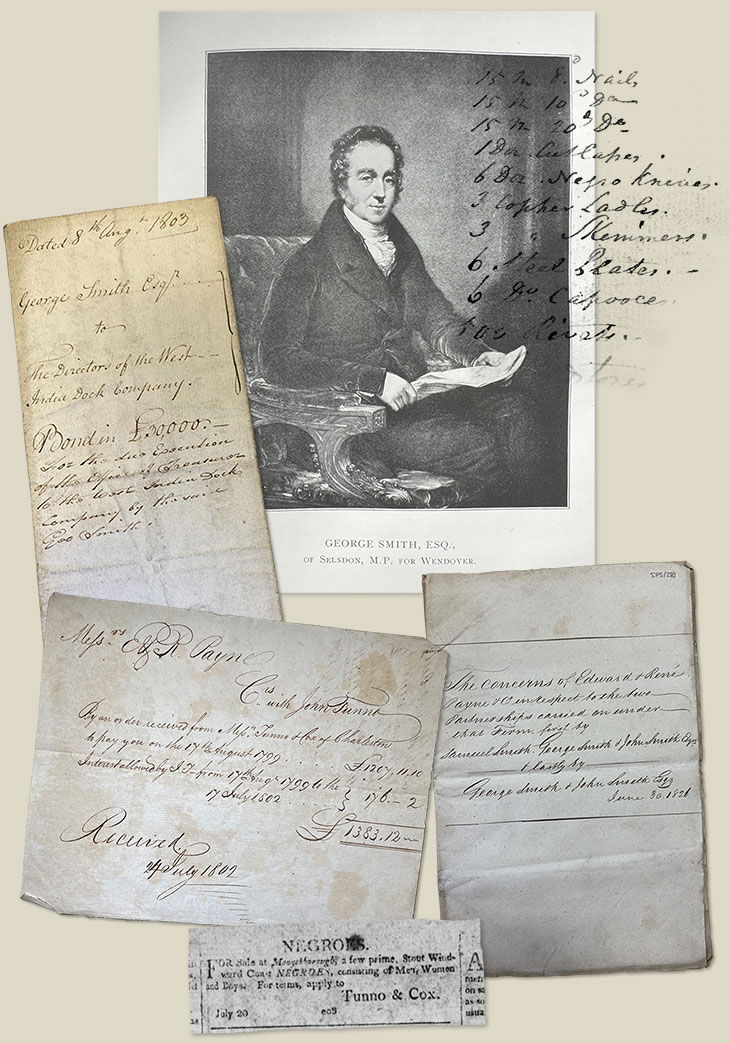

In 1791, at age 25, George Smith gained a seat in parliament. There, he voted for greater rights for two of Britain’s most oppressed minorities at the time – Catholics and Jews – and supported electoral reform to enfranchise more people. A political rival declared in one debate that “a more honourable man did not exist.”

But Smith appears to have stayed silent on the slavery trade at key moments in Parliament. He didn’t take part in an unsuccessful April 1791 vote on abolition of the trade, according to voting records, or in two other failed abolition votes.

Whatever his reasoning, one fact is clear: Ending slavery would have been bad for the family business.

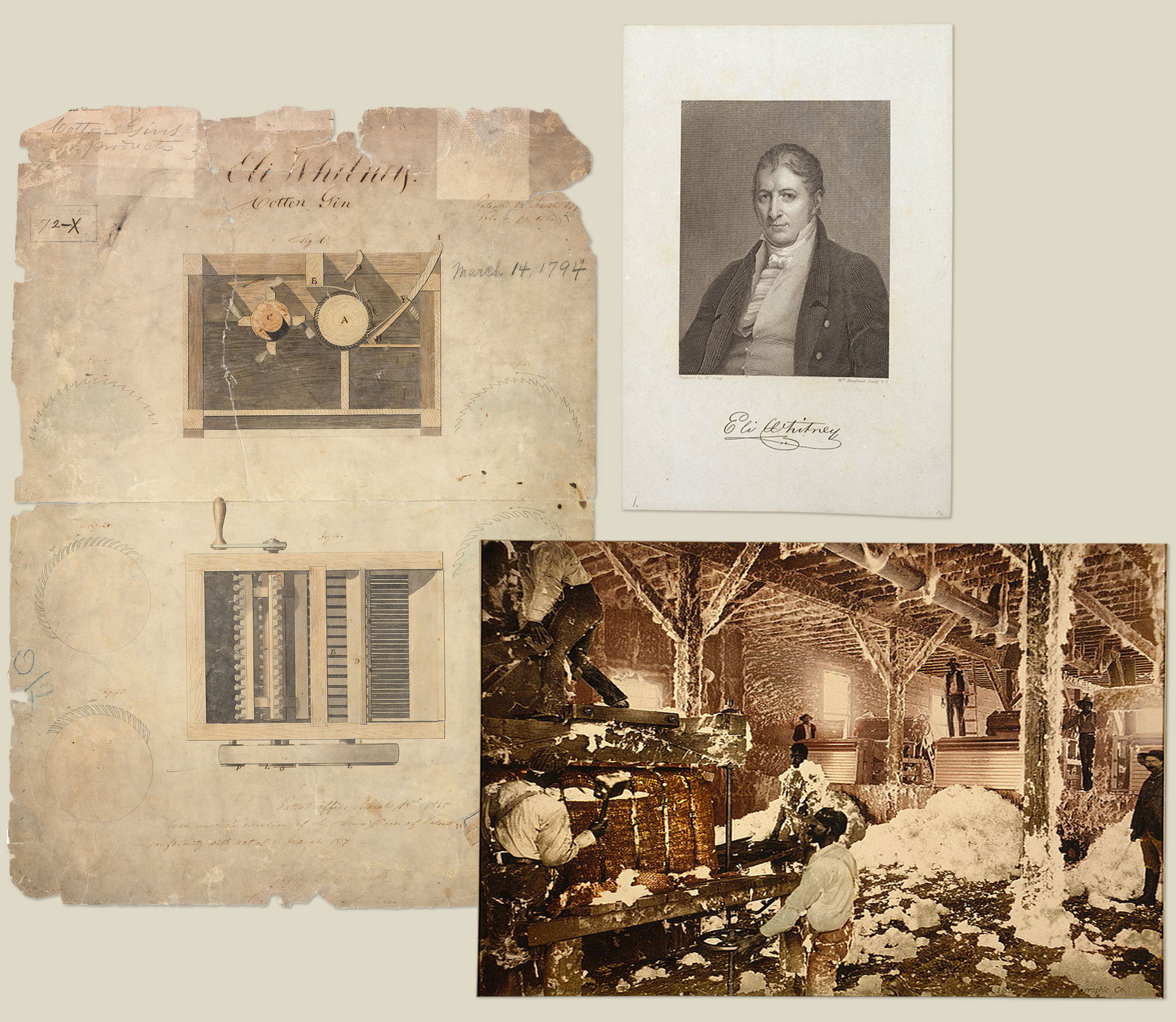

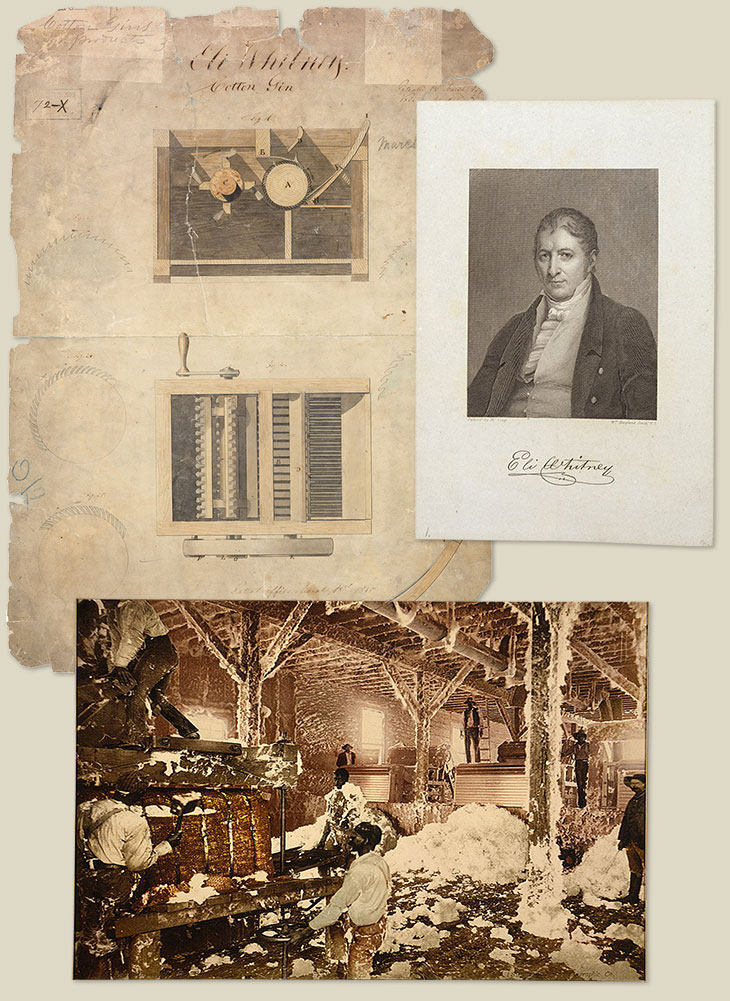

In 1794, Eli Whitney patented the cotton gin, a machine that would transform the U.S. slavery economy. That year, George Smith was working at his family banking business, which was founded in Nottingham, a center of the British cotton industry. Mill owners including the Arkwrights, one of the richest families in the industry, were Smith family clients.

By the 1820s, George Smith was also providing credit to cotton brokers in Liverpool – the primary destination of U.S. cotton in the pre-Civil War era.

Other British banks such as Barings and Rothschild were more active in funding the shipment of cotton. But the firm that was likely the largest player was founded by ancestors of another member of parliament today, Geoffrey Clifton-Brown.

Reuters found that Clifton-Brown’s direct ancestors included brothers William and James Brown, who founded Brown Brothers along with other family members. (William’s son married the daughter of James, and their son was Clifton-Brown’s great-great-grandfather.)

Geoffrey Clifton-Brown

Member of Parliament

DIRECT ANCESTOR William and James Brown

RELATIONSHIP Great-great-great-great-grandfathers

ROLE IN SLAVERY ECONOMY The Brown brothers, with other family members, co-founded the trading and banking empire that would become Brown Brothers Harriman, a bank that provided credit to slaveholders and traded in goods produced by enslaved labor, such as U.S. cotton.

The Brown brothers’ firm was the precursor of banking house Brown Brothers Harriman & Co, now based in New York. At one point, the American firm controlled 15% of all cotton shipments into Liverpool. Brown Brothers Harriman declined to comment. The bank says on its website that its role helped to “perpetuate the Southern plantation economy and its use of slave labor, a source of profound regret today.”

The Brown brothers, one based in Liverpool and the other in New York, supported all stages of the cotton supply chain from plantation to mill, including shipping goods in their own vessels. When some clients defaulted in the 1830s, Clifton-Brown’s great-great-great-great-grandfathers took possession of several plantations in Louisiana and Mississippi. The properties had hundreds of enslaved workers when they were sold by the firm almost 20 years later.

Clifton-Brown declined to comment for this story.

George Smith also owned bonds from banks that lent money to American plantation owners, including the Planters Bank of Tennessee and the Planters Bank of Mississippi. The bonds were valued at more than 10,000 pounds – 12.8 million pounds in today’s money, by one calculation. Leather-bound ledger books from the time illustrate that the purchase of bonds from planters’ banks was widespread in Britain, including among the middle class.

Financial historians say slavery-linked financing, from Baring’s funding of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 to retail bond sales and the development of tools for hedging cross-border cotton sales, helped build London into the global fulcrum of finance that it is today.

“The financial system that was built in the course of the 18th century was significantly shaped by the needs of this slave economy – credit, instruments of exchange and trade – so that the acceleration of the financial revolution was, in part, a function of the slave economy,” said Draper, who was a senior investment banker at JP Morgan Chase & Co before becoming a historian.

Absentee owners

Here in Jamaica, the Smith family owned three plantations west of Kingston with a total of 237 enslaved people in 1798, records show. The largest of the plantations, Farm Pen, evolved from producing sugar to rearing cattle and growing crops for the local market. It sat on land alongside the Rio Cobre between Kingston and Spanish Town, an early capital of colonial Jamaica.

Two British travel writers visited Farm Pen in 1837, when the land was still in Smith family hands. Slavery had been abolished on paper, but workers were still forced to labor there. The writers, Joseph Sturge and Thomas Harvey, noted that the plantation was “furnished with that relic of former times, the stocks.”

Such business helped make George Smith wealthy. He acquired a country estate, Selsdon, south of London, where he built a neo-gothic mansion with turrets and archways. The estate, with gardens and parkland, was featured in books and periodicals that were the 19th-century equivalent of modern celebrity lifestyle magazines.

Like many British plantation owners, the Smiths were absentee landlords. The day-to-day running of the plantations in Jamaica was left to a manager, who kept the family informed of developments. But that didn’t mean they and other owners were uninvolved.

Owners, generally, would often be “spurring on” the managers, said Radburn, the historian at Lancaster University: “‘OK, we need more, we need to increase production, or we need to buy more people to increase my income.’” The money enabled lives of “frivolous, conspicuous consumption,” he said. “It’s often so they can go on a grand tour of Europe, so they can build a new wing on the country house.”

The Smiths and their partners gained control of more plantations – and more than 700 enslaved workers – in the late 1820s, when a large customer defaulted.

One of their plantations was the Holland Estate in St. Elizabeth Parish on the west of the island, an expanse of about 4,000 acres surrounded on three sides by wooded hills and bordered to the south by the Black River. The Smiths’ share was just under 40%.

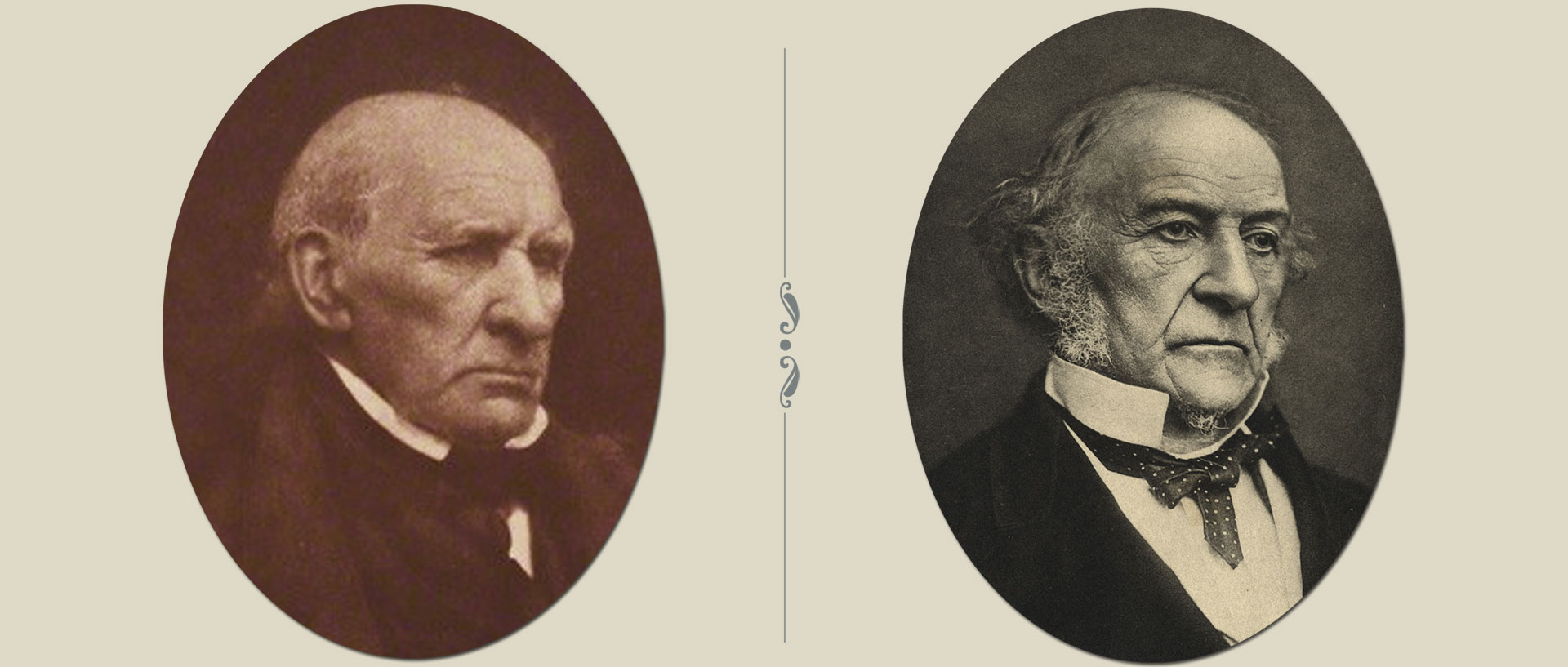

The lead creditor, John Gladstone – father of future British Prime Minister William Gladstone – enlisted the Smiths to join him in purchasing an additional 118 enslaved people in the hope of doubling sugar output, documents reviewed by Reuters show.

John Gladstone

William Gladstone

John Gladstone’s letter to George Smith and partners

In 1833, parliament voted to end slavery. The Slavery Abolition Act took effect in 1834 – but for several years the newly freed workers would be forced to toil for their former enslavers without pay. Their so-called apprentice status kept them in the fields, although they had to be compensated to work over 45 hours a week. Parliament voted to end the apprentice system in 1838.

While John Gladstone had operational control of the estate, he kept the Smiths abreast of affairs with regular and detailed updates about costs and revenues at Holland. He sought their approval for changes in managerial or working arrangements, letters show. The Smiths’ replies to Gladstone have not survived.

Gladstone’s letters emphasized details relating to bad weather or other operational misfortunes. Yet he conveyed little interest in the welfare of the enslaved, discussing only their productivity. In one letter, dated August 13, 1834, he discussed the plan to “break in the negroes by degrees.”

Robertson Gladstone’s Letter to Estate Manager

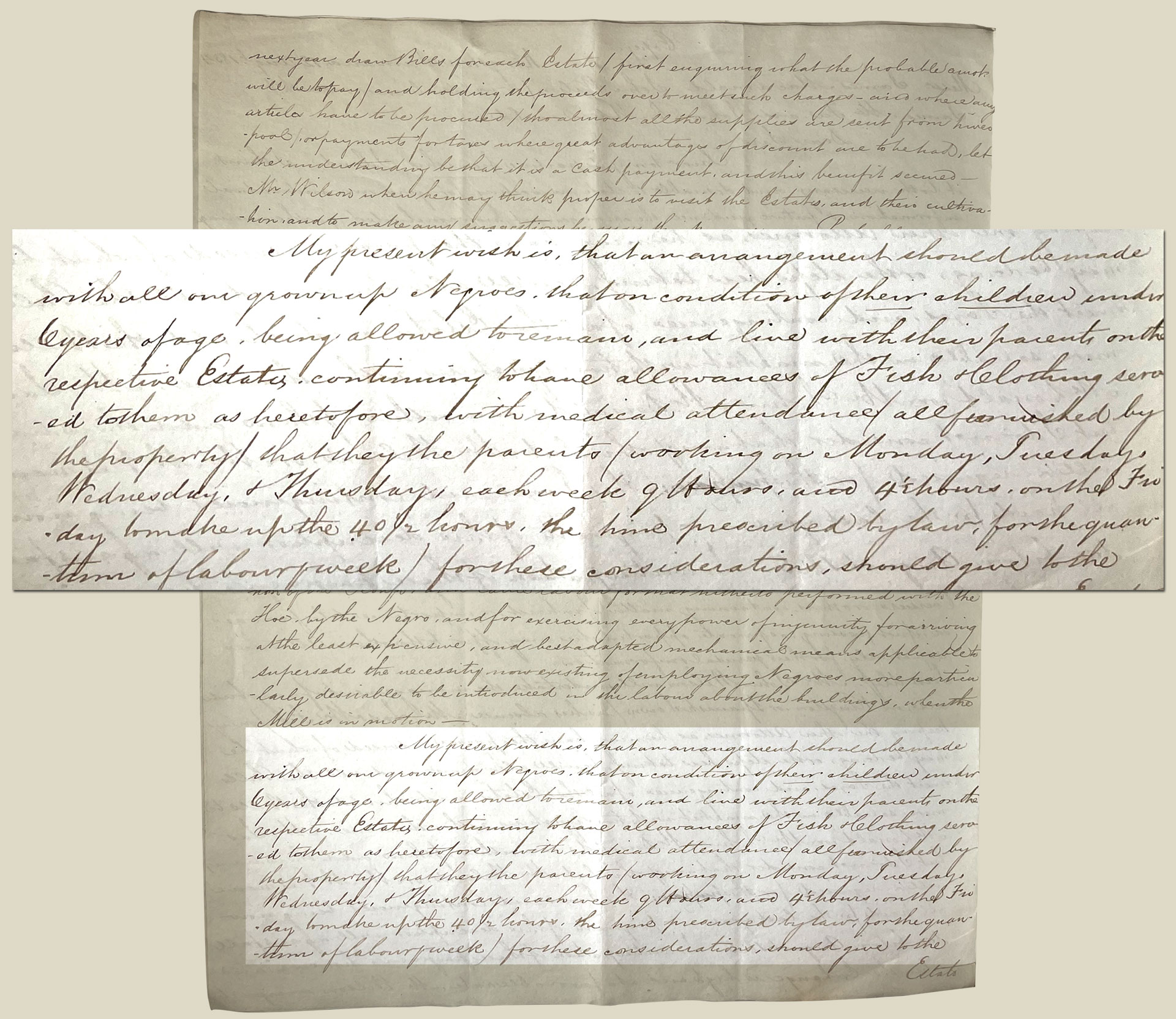

“My present wish is that an arrangement should be made with all our grownup Negroes that on condition of their children under 6 years of age being allowed to remain, and live with their parents on the respective Estates continuing to have allowances of Fish & Clothing served to them as heretofore, with medical attendance/ all furnished by the property/ that they the parents/ working on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, & Thursday each week 9 hours, and 4 ½ hours on the Friday to make up to the 40 ½ hours, the time prescribed by law for the quantum of labor/week/ for these considerations should give to the …”

Another letter, written by Gladstone’s son Robertson, discussed the reluctance of apprentices to work hours above the statutory limit for a fee. Robertson Gladstone proposed that food rations should be denied to children under the age of 6 – children older than 6 worked – unless their parents agreed to the additional hours.

“If they are not disposed for their children’s sake to avail themselves of so advantageous an offer it would be well at least for a time to withhold all supplies,” Robertson Gladstone wrote to the estate’s manager, on behalf of all the owners.

Typically, those rations supplemented food provided by the children’s parents, who were allowed to cultivate small plots of land, historians say.

When Britain abolished slavery, the government offered no compensation to the enslaved. But it did compensate their enslavers for the loss of what was considered their property: the people they had held in bondage. Britain borrowed 20 million pounds in 1835, equivalent to about 40% of the government’s total annual expenditures, to pay slaveholders.

Ledgers from the time, preserved in Britain’s National Archives, record the names of George Smith and his relatives as recipients of almost 3,000 pounds in compensation for losing the people enslaved at Holland Estate alone – by one calculation, some 4 million pounds in today’s money.

Smith died in 1836.

‘A universal wrong’

The warehouses the Smith family funded in the old West India Dock in London’s East End still stand. There, ships once unloaded goods from Jamaica and other Caribbean colonies. A plaque at the dock entrance bears its original inscription, announcing an undertaking that “under the favour of God, shall contribute stability, increase and ornament to British commerce.”

The buildings are dwarfed now by the glass and metal skyscrapers of Canary Wharf, built on the former docks. And yards behind the plaque at West India Docks is an empty pedestal.

Until 2020, it held a statue of Robert Milligan, one of the founders of the docks, who also traded in enslaved people and owned plantations in Jamaica. It was removed in 2020, during protests inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, which helped accelerate a re-examination of Britain’s links to slavery.

Very few people living in Britain owned slaves – less than 0.1% of families when parliament voted to end slavery in Jamaica and Britain’s other colonies. In U.S. states where slavery was legal, in contrast, there was about one slaveholder for every four households in 1860, the year before the start of the Civil War.

That might explain why a recent poll pointed toward an ambiguity in British public opinion. The 2021 Ipsos survey showed that Britons were evenly split between those who said they are ashamed of the nation’s involvement in slavery and those who said they are proud that the UK was one of the first countries to abolish the trade – 20% on each account. Another 18% said they feel both proud and ashamed, and 42% said either that slavery was too long ago to feel either way, or that they didn’t know.

Some Conservative Party politicians and academics have pushed back against efforts to explore how historical figures and institutions benefited from slavery.

Former Prime Minister Boris Johnson in 2022 bemoaned the toppling of a statue related to the slavery trade, saying, “What you can’t do is go around seeking retrospectively to change our history.”

And current Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has rejected calls for Britain to apologize to Caribbean countries or pay reparations, saying that “trying to unpick our history is not the right way forward.”

Views are different in Jamaica, across the Atlantic.

Today, the land where the Smith plantation Farm Pen sat is owned by Jamaica’s government. The place is overgrown with grass, palm trees and acacias, and the fields are dotted by piles of dumped rubble.

A few miles away, in capital Kingston, Mayor Delroy Williams earlier this year pointed toward the turquoise waters of the harbor. “This was where the ships transporting Africans from West Africa docked,” Williams said. “But do we want to just remember here as that? No, we really want to move Kingston and move Jamaica, into an era of self-respect, of honor, and of dignity, human dignity.”

Vast wealth was sent to Britain, he said, with no regard for “the devastating consequences to Jamaica and to other countries that experienced this system.” By slavery’s end, more than 1 million people had been forcibly taken from Africa and sent to Jamaica, according to data compiled by academics.

“Not to feel guilty for a universal wrong would be wrong,” said Williams, who favors reparations for the many ills left in slavery’s wake. “All the benefits derived from slavery come right down to the current British society and the negative impact on the Jamaican society.”

In the past decade, Caribbean leaders have publicly called for Britain to pay reparations for its role in slavery. In 2013, CARICOM, an intergovernmental organization of more than a dozen member states in the region, established a commission on the subject. Its chairman has argued that Britain owes the descendants of the enslaved 76 billion pounds, saying in 2017 that the funds would be used to revitalize the region in “a Marshall Plan to help to clean up this mess that we inherited.”

Near another former plantation where George Smith’s firm once did business, Winsome King sells ackee fruit from a market stall. She too favors reparations.

“Some people say forget about it, but some people only forget about things that doesn’t happen to them,” she said. The British, she said, “should do the right thing.”

Profiting from slavery

Reuters examined the genealogies of some of Britain’s most notable politicians and found, in many levels of government, descendants of people who participated in aspects of the slavery economy. Reuters scrutinized thousands of pages of documents, including birth records, guides to royal peerage, wills, corporate records and correspondence. The work was then reviewed by Rachel Lang, an author and honorary research fellow at University College London. Lang previously was a primary researcher and genealogist for a research center at UCL that documented the sweep and depth of British slaveholding.

Among the notables who, Reuters found, have ancestral ties to merchants who profited from slavery:

Slide the bar to see the profiles

A REUTERS SERIES

PART 1

INTERACTIVE

PART 2

PART 3

Slavery’s Descendants

By Tom Bergin

Visuals editor: Jeremy Schultz

Art direction and illustrations: Catherine Tai

Design: John Emerson

Edited by Cassell Bryan-Low, Tom Lasseter, Janet McBride and Blake Morrison