If there’s one thing we hope that this year’s ‘80s Week package better illuminates, it’s the incredible depth and range on display in the films of the decade. While the iconic movies and stars of the totally radical ‘80s tend to most easily remembered for neon-tinted, big-haired, Tangerine Dream-set turns, consider this: the decade included all-time work from major performers like Meryl Streep, Ossie Davis, Jessica Lange, Robert De Niro, Gena Rowlands, Daniel Day-Lewis, Paul Newman, Jackie Chan, and Whoopi Goldberg.

If there’s one thing we hope that this year’s ‘80s Week package better illuminates, it’s the incredible depth and range on display in the films of the decade. While the iconic movies and stars of the totally radical ‘80s tend to most easily remembered for neon-tinted, big-haired, Tangerine Dream-set turns, consider this: the decade included all-time work from major performers like Meryl Streep, Ossie Davis, Jessica Lange, Robert De Niro, Gena Rowlands, Daniel Day-Lewis, Paul Newman, Jackie Chan, and Whoopi Goldberg.

These are the kind of stars who show up and show out no matter the year, but it’s in the ‘80s in which they all captured the incredible essence of what makes them greats.

But they’re hardly alone on this list, which also includes indelible work from stars like David Byrne, Sandrine Bonaire, Babak Ahmadpour, Seret Scott, Mieko Harada, Ken Ogata, and even Divine — all names that deserve more recognition, both then and now. Not convinced? One last shot: this list doubles the performances we spotlighted from the ‘90s — doubles! — an ask that proved to be almost too easy. The only problem? We had more performances we wanted to include, a true embarrassment of riches.

Selected from a decade that boasts iconic performances, indelible breakouts, and the best work of some talents who only ever churn out top-tier work, here are the 50 performances that we can’t help but champion.

This article includes contributions from Carlos Aguilar, Susannah Gruder, Jim Hempill, Guilherme Jacobs, Sean Malin, Vikram Murthi, and Mark Peikert.

-

Isabelle Adjani as Anna/Helen in “Possession” (1981)

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection As she flails, shrieks, and whips herself around in a squalid Berlin subway tunnel in the now-iconic scene midway through “Possession,” it’s difficult to say whether Isabelle Adjani is undergoing an exorcism or in the process of being possessed herself. With overwhelming physicality, Adjani gives herself to the role of Anna, an inscrutable woman seeking a divorce from her husband Mark (Sam Neill) for reasons that aren’t clear from the start. Not that things get any clearer as the film goes on. As each character’s actions become increasingly deranged, Adjani’s on-screen presence becomes a strangely grounding force.

While clearly in the throes of both physical and emotional upheaval, Adjani emanates a beguilingly subtle power. Much of this comes from the repeated looks she exchanges with us, her audience — her uncanny, knowing gaze signaling that she’s aware of something that both we and her husband are not. Her ecstatic, manic meltdown in the subway is still one of the most haunting, perplexing sequences ever filmed. Perhaps she’s miscarrying an otherworldly entity, the result of her affair with the oozing, slug-like creature she’s been sleeping with and worshiping like a god. Or perhaps it’s, as she describes it, a miscarriage of faith. Either way, it’s impossible not to feel reverence for Adjani, as if we’re in the presence of a god-like being ourselves.

The role took a toll on Adjani. She reportedly experienced PTSD and required therapy for years afterward. Director Andrzej Żuławski was known for his punishing techniques, with Neill referring to him as a “genius, but crazed.” But Adjani brings her own previously untapped store of feverish genius to the role, taking ownership of “Possession” and creating something unique, absurd, and altogether sublime in the process. —SG

-

Babak Ahmadpour as Ahmad Ahmadpour in “Where Is the Friend’s House?” (1987)

There’s the child actor Enzo Staiola in “Bicycle Thieves,” then there’s Babak Ahmadpour in “Where Is the Friend’s House?” This is one of the most purely naturalistic performances from a child that’s ever been committed to film, and, like Staiola in De Sica’s film, Ahmadpour had never acted before. Director Abbas Kiarostami found him in the northern Iranian village of Koker along with the other child actors in the film.

His character, Ahmad, is an extremely good kid. Watching him watch his friend Mohammed, who’s been forced to tears by his teacher for the fact he keeps forgetting to bring his notebook to school, is how we get to know Ahmad. As Mohammed (played by Babak’s real-life brother) breaks down, Kiarostami’s camera mostly avoids focusing on Mohammed in his puddle of tears, the teacher berating him outside the frame. The lens is trained instead on Ahmad’s face, watching his friend with increasing concern. He’s projecting such empathy for his friend that you can’t help but feel intense protectiveness for Ahmad too.

Throughout the movie, Ahmadpour can barely raise his voice. He’s too polite to insert himself too forcefully into any situation, even as he’s running between two towns trying to find Mohammed to return his notebook to him. Yep, the kid left it behind again. And Ahmad’s night journey of the soul to return it to him leaves you impossibly worried for him: Ahmadpour underlines nothing, even as Kiarostami puts him in the most exasperating situations like when a workman wants to tear a page out of Mohammed’s notebook to use to write up a receipt. Agonizing! Ahmad’s too polite to object, of course.

Thankfully, Ahmadpour survived a terrible earthquake that hit Koker in the aftermath of “Where Is the Friend’s House?” and even appeared in Kiarostami’s later film “Through the Olive Trees.” It’s believed he works in a mall in Tehran. —CB

-

Isaach de Bankolé as Protée in “Chocolat” (1987)

Image Credit: Claire Denis It’s a testament to director Claire Denis and her extraordinary long-term collaborator de Bankolé that he absolutely runs away with this film about life in colonial French West Africa as otherwise seen primarily through the lens of the colonizers. His Protée is the beating heart of the movie. As a house servant for a colonial magistrate, his wife, and their daughter (a stand-in for Denis, who grew up in French Cameroon), he’s the person responsible for making everything about their cushy lives possible. And he’s developed a friendship with the young girl (Cecile Ducasse), putting smushed ants on her bread as a dare to eat it — and she does!

Protée is intimately involved with most aspects of the family’s life, except that there’s no intimacy in their relationship. He is always kept apart. Except for when the wife (Giulia Boschi) decides she needs him — her husband, often absent, is not providing her intimacy either. At least in the way she wants. In one long-shot, Denis’ camera placed on the other end of the room, we see the wife, sitting, as Protée draws the curtains, and her hand snakes up his leg in a seductive gesture. Denis never cuts in for this moment. She trusts you to understand the magnitude of it even from afar. But Protée simply finishes his task, then bends down and picks her up suddenly as if to snap her out of her delusion. He’s not taking the bait.

And that’s even as much as he does want a greater intimacy with the family. When he’s showering, he hides himself from their view, then turns away and weeps. De Bankolé creates such an impressive sense of Protée’s internal life — the gap between what he projects and what he really feels — that he’s an irreducible figure. Not a savior, not a villain, not a stereotype, he’s a fully realized flesh-and-blood human, whose final difficult choice may almost seem monstrous, while also being an act of self-preservation for all parties. You can see why Jarmusch came a calling, then “The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles” and finally major Hollywood projects such as “Casino Royale” and “Black Panther.” But that de Bankolé has never stopped making art films, as well, shows the restless searching that underlies his talent. —CB

-

Sandrine Bonnaire as Mona in “Vagabond” (1985)

Image Credit: MK2 Diffusion Coming just two years off her film debut at age 15 in Maurice Pialat’s “A Nos Amours,” Sandrine Bonnaire’s performance in Agnès Varda’s “Vagabond” is a shock to the system — a startlingly self-assured turn from such a young actor. Her character Mona’s age is impossible to guess. As a drifter who’s abandoned society to live on her own terms, Mona is, in many ways, mature beyond her years.

She’s been hardened by life as a young woman on the road, and has put up a wall to protect herself from the world, and the men who try to take advantage of her. At the same time, her youthful spirit and stubbornness is still largely intact — Mona’s chosen lifestyle has, in a certain sense, extended her childhood, allowing her to do what she wants when she pleases, without a job to rely on or a boss to answer to. When she doesn’t get her way, this childishness creeps in. Caked in dirt, messy curls blowing in the wind, Mona pouts or cries out in anguish when the few possessions she prizes are compromised — a loaf of stale bread that’s no longer edible, a painting with a hole through the canvas. Bonnaire’s ability to straddle the line between youth and adulthood, between reveling in her solitude and raging against loneliness, is what makes Mona so bewildering, inspiring a mix of confusion, fear and compassion in those she meets, and in us. —SG

-

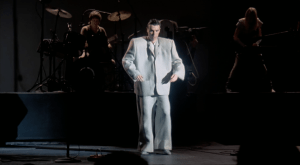

David Byrne as David Byrne in “Stop Making Sense” (1984)

Image Credit: A24 So much more than The Big Suit, David Byrne’s performance in Jonathan Demme’s legendary Talking Heads concert film exists in a realm that only movie cameras could ever hope to capture. Watching the show from the crowd, it would probably be impossible to fully appreciate the way the singer’s eyes remain unblinking while he bobs his head like a chicken during “Psycho Killer.” Or to understand the dexterity required for the Fred Astaire pas de deux that Byrne performs with an electric lamp on “This Must Be the Place.” Byrne understood that he wasn’t just on stage, but also on film, and he calibrated his performance for the cameras to maximum effect.

You notice first how Byrne’s always in motion. Sure, he’s a lyricist, a singer, and a visual artist — the guy’s an intellectual. But he never forgets the importance of feeling the groove, and of giving physical expression to the music: This is the smartest guy in the room, yet he never just lives in his head. You know he’s really feeling it too because he doesn’t care if he looks goofy, which he does a good bit of the time. Sometimes his dancing is just him running in place. That makes it feel all the more spontaneous and improvisatory, even as it’s all clearly planned with care.

The contrast between Byrne’s buttoned-up exterior and the wild abandon of his dance moves — sometimes bending his back limbo-style like he might fall — has captivated viewers for decades. He’s the flesh-and-blood projection of how the audience feels hearing the music, and the living embodiment of what we all wish we could be if only we were less self-conscious. —CB

-

Pat Carroll as Ursula in “The Little Mermaid” (1989)

Image Credit: ©Walt Disney Co./Courtesy Everett Collection “Life’s full of tough choices, innit?” One of Ursula the Sea Witch’s most iconic lines, delivered with astonishing gusto by Pat Carroll, also describes the casting process for her role. In hindsight, it’s unthinkable that she wasn’t the first choice to portray the villain. Directors John Musker and Ron Clements wanted to hire someone from Broadway or television for the role; Joan Collins and Bea Arthur were initially sought to play Ursula, and Elaine Stritch actually was cast before departing after a clash with lyricist Howard Ashman.

Carroll was certainly known when she was finally cast — she had been on TV for nearly 40 years at that point, dating back to “The Red Buttons Show,” but she got the part because of her deep, husky voice layered with camp, not because she was a big-screen star with box-office clout. Much has been made of how the look of Ursula was inspired by Divine, and Carroll brings a bawdy, sleazy, sensuous purr to match the animation. Think of the moment in her villain song “Poor Unfortunate Souls” when she opines about the importance of “body language,” a moment of perfect synchronicity with the animators, who gave Ursula a lusty shake of her rump.

“The Little Mermaid” is a tale of that first venture forth from home and family that everyone has to make in life. It’s a story of budding sexuality and the exploitative forces that want to manipulate it (very ‘80s themes), much like another musical juggernaut from the decade, “The Phantom of the Opera.” In that poperetta, the Phantom commands, while singing himself, for his young muse to “Sing! Sing for meeee!” And… that’s exactly what Ursula does to Ariel in “The Little Mermaid” too. But of course Michael Crawford won a Tony Award for “Phantom” and Pat Carroll was nominated for nothing. Or as Ursula would say, “How rude!” —CB

-

Jackie Chan as “Kevin” Chan Ka-Kui in “Police Story” (1985)

Image Credit: Golden Harvest In a decade stacked with some — or even most — of the greatest action movie performances the Hong Kong film industry has ever produced, Jackie Chan still managed to plow a car through the competition, then speed away from the field by using an umbrella to grapple onto a bus, and finally get high enough to make a death-defying leap to Hollywood in the hopes of grabbing onto some string lights that might slow his fall. It’s foolish to compare Chan’s Keaton-esque bravado to the rival genius of peers like Sammo Hung, Michelle Yeoh, or Donnie Yen, but his performance as supercop “Kevin” in his self-directed “Police Story” crystallizes the showmanship that has made him such a singularly international star.

Chan’s irrepressible energy and Magoo-like athleticism allow him to execute some of the most breathtaking stunts this side of the silent era — grin his way through some of the broadest slapstick this side of the silent era — all while successfully convincing Maggie Cheung not to break up with him, which is the kind of juggling act that earns Chan his comparisons to the early cinema icons who inspired him. When he’s firing on all cylinders, he feels like one-of-a-kind. —DE

-

Beatrice Dalle as Betty in “Betty Blue” (1986)

Image Credit: ©Alive Films/Courtesy Everett Collection / Everett Collection Roughly two decades before the “manic pixie dream girl” entered the lexicon, Beatrice Dalle effectively invented her opposite: A spirited, volatile, gap-toothed incarnation of raw sexual id who sweeps into the life of a wannabe writer named Zorg (Jean-Hugues Anglade) and, unable to square their happiness with her violent spirit, drags the both of them into a deathward spiral that finally makes good on her boyfriend’s literary ambitions. Imagine if “Garden State” had been written by Lars von Trier and directed by Luc Besson and you’ll be on the right track.

If nothing else, this eye-popping epic from the cinema du look is the hottest movie that ever ended with its female lead gouging out her own eye, but Dalle’s performance is so committed to the cause that it allows this massive pop spectacle to remain firmly grounded in real emotion at all times, and its excesses — of the both the aesthetic and emotional varieties — to feel like natural symptoms of a love story that isn’t validated by the world at large.

Few screen performances over the last 40 years have seen an actor more fearlessly parodying their own youthful beauty, as Dalle’s Betty reflects all of the most inane desires that she’s capable of provoking from men. She’s wholly consistent in her feral capriciousness for the film’s entire three-hour running time, the actress always finding new and increasingly stressful ways to self-destruct the male fantasy of a dream woman who only exists to fix them. —DE

-

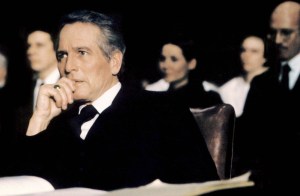

Daniel Day-Lewis as Christy Brown in “My Left Foot” (1989)

Image Credit: Palace Pictures Let’s just get this out of the way: yes, it is old, old hat to praise Daniel Day-Lewis for acting. We might as well put a Beatles song on a list of the best music of the 1960s.

But there is simply no use in trying to ignore a performance that changed film acting forever. It’s often said that a good actor stops pretending and starts being. As Christy Brown, the artist who learned to paint with the eponymous appendage due to cerebral palsy, Day-Lewis reached a level of embodiment still unmatched by the Jeremy Strongs, Joaquin Phoenixes (Phoenices?), and even method-nightmare-in-human-form Jared Letos of the world. In order to authentically emulate the wheelchair-bound Brown, the English actor famously learned to write with his toes and asked crew members to feed him by hand during production. He attempted to become Brown, and by all accounts succeeded.

Difficult as that must have been for the production, Day-Lewis’ commitment earned him the first of three Academy Awards for Best Actor (the most of any man living or dead) and a reputation as the greatest actor of his generation. It remains one of the rare roles whose hype matches its execution. Besides his physicality, which so closely mimicked the real-life Brown’s, Day-Lewis’ full emotional range is startling, jumping from misery to joy and back again like a hailstorm in broad daylight. His depiction is mercurial, angsty, alive — and as a result, the film plays not like a tragedy, or even like a biopic, but like a comedy. Despite playing a man whose life must have been so much harder than most people’s, Day-Lewis makes it all look strangely easy. —SM

-

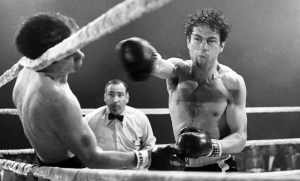

RAGING BULL, Kevin Mahon, Martin Denkin, Robert De Niro, 1980. (c) United Artists/ Courtesy: Everett

Image Credit: ©United Artists/courtesy Everett / Everett Collection Is this the best performance of the ’80s? Maybe. What’s more certain is that’s the general consensus around De Niro’s turn as boxer Jake LaMotta in Martin Scorsese’s masterpiece. In an era where we’re inured to stars drastically altering their appearance for an awards run, De Niro’s physical transformation remains the gold standard. For his passion project (De Niro brought it to Scorsese), the actor immersed himself so thoroughly in the sweet science that he allegedly won actual boxing matches. Then he gained enough weight to effectively play the retired La Motta — and garnered breathing problems in the process. But this isn’t just a “He got fat, give him awards!” performance. De Niro is at his most charismatically terrifying as a loser who eeked out some success before destroying it all with paranoid, violent outbursts. You’re terrified of him, you pity him, but you also, to a certain degree, understand him. —MP

-

Divine as Francine Fishpaw in “Polyester” (1981)

Image Credit: ©New Line Cinema/Courtesy Everett Collection John Waters’ suburban satire “Polyester” — which stars the Pope of Trash’s late muse, Divine (née Harris Glenn Milstead), and the then-aging Hollywood hottie Tab Hunter — takes aim at ‘60s domestic melodramas, otherwise dubbed as “women’s films.” Playing against her usual bawdy, brazen type, Divine shows unusual reserve as Francine Fishpaw, a put-upon Baltimore housewife whose porn-peddling husband, Elmer (David Samson), is having an affair with his secretary and whose daughter and son are at extreme levels of self-centered and psychopathic, respectively.

When Elmer, who owns an X-rated theater, leaves his wife, she experiences brief bliss after meeting a mysterious blonde bachelor, Todd Tomorrow (Hunter), while cheered on by her delusional best friend, Cuddles, played by Waters’ regular Edith Massey. But Francine’s happiness is short-lived, as her savvy schnoz, which is especially attuned to foreboding and booze, picks up the scent of another, particularly soul-destroying betrayal.

From its original title track to its many dark turns — which emphasize that there are no happy endings, especially in Pleasantville — “Polyester” conjures the magic of midcentury cinema, down to an olfactory experience that literally employed the foully immersive Smell-O-Vision gimmick in theaters. Waters’ usual partner in crime Divine shows a softer side to herself than the one we’re used to seeing in films like “Pink Flamingos” and “Female Trouble” — though, of course, she ultimately goes full gross-out freak-fest even when she’s demurely puking into her purse.

As Francine sniffs out her husband’s extramarital affair, her freebasing boyfriend’s antics, and all sorts of very Waters-ian disasters, Divine’s performance becomes increasingly unhinged to match her filmmaker, a filth-filled toast to their great cinematic marriage. Divine shows that she can be the conduit between Waters’ nasty low-rent early works and his later tendency toward ironic sentimentality. Here she’s playing the victim rather than the perpetrator of insanity, making way for Divine’s most nuanced performance. —RL

-

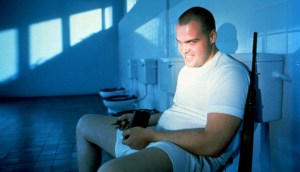

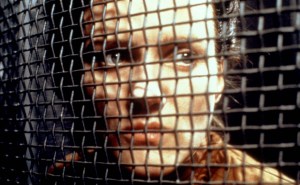

Vincent D’Onofrio as Private Leonard “Gomer Pyle” Lawrence in “Full Metal Jacket” (1987)

Image Credit: ©Warner Bros/Courtesy Everett Collection Because Vincent D’Onofrio had barely been seen on screen before his 1987 turn as Private Leonard “Gomer Pyle” Lawrence in “Full Metal Jacket,” audiences at the time didn’t realize how physically transformative the performance was — though a few attentive moviegoers might have noticed the much skinnier D’Onofrio in a brief supporting bit later that summer in “Adventures in Babysitting.” What couldn’t be denied was the emotional power of a role that was sad and terrifying in equal measures, expertly played by an actor capable of hitting every note on the emotional scale without a misstep.

D’Onofrio’s character makes a startling exit from Stanley Kubrick’s pitch-black Vietnam War film about halfway through, but the actor’s haunting portrayal of an affable dope turned psychopath haunts the rest of the movie, and stays with the audience long after the unsettlingly ironic finale. It takes a lot to give a performance that fully realizes all of the potential in a script as rich and morally challenging as “Full Metal Jacket,” but D’Onofrio goes even further: his abrupt shift from victim to killer informs the bifurcated structure of the movie as a whole, and puts him in a class with Malcolm McDowell and Jack Nicholson among Kubrick’s most memorable murderers. —JH

-

Shelley Duvall as Wendy Torrance in “The Shining” (1980)

Image Credit: ©Warner Bros/Courtesy Everett Collection Shelley Duvall’s experience making Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining” has been the subject of fascination, derision, gossip, and rumor for over four decades, all that chatter often obscuring at least one immutable truth: she’s extraordinary in the role. Nothing about Kubrick’s iconic take on Stephen King’s also-iconic novel of the same name is easy — and, yes, that’s slamming years and years of academia and discussion on the subject into one extremely short conclusion — but the result is a classic horror feature that elides all easy designations.

And yet, it was tremendously misunderstood when it was released in 1980 — earning both Kubrick and Duvall Razzie nominations for their work, a profound miscarriage of critical justice that should have ended those cruel “awards” right then and there (the nomination was ultimately rescinded in 2022). Alas, Duvall’s deeply emotive, woundedly open, and staggeringly relatable performance in the midst of a mad milieu has endured these many years, and is finally garnering the respect it’s long deserved.

What would you do if you were Wendy Torrance? At the mercy of the whims of her mercurial husband Jack (Jack Nicholson), worried about the mental stability of her only child Danny (Danny Torrance), and forced into a months-long isolation with them at the cursed Overlook Hotel. You would be afraid, would you not? And the fear that Duvall brings to the role – a primal, eye-popping, stomach-clenching fear that’s hard to fake and even harder to ignore – gives ballast to this nightmare as it spins wildly out of control. Wendy might be the only real person at the Overlook, both figuratively and literally, and the unquenchable terror that Duvall pours into every scene, every frame, every look is as riveting as it gut-churning. Nothing feels more true, nothing is more scary. —KE

-

Whoopi Goldberg as Celie Harris Johnson in “The Color Purple” (1986)

Image Credit: ©Warner Bros/Courtesy Everett Collection It takes about an hour for Whoopi Goldberg to appear in Steven Spielberg’s “The Color Purple,” the director’s melancholy adaptation of the Alice Walker novel set in a post-Antebellum, early-20th-century Georgia. The headstrong and grown-up-too-fast Celie Johnson is first played by Desreta Jackson before she turns into the traumatized and meek-mouthed (at first) version played by Goldberg in the film’s 1920s.

Celie is ever in awe of the stronger women who come and go from her life, from Sofia (Oprah Winfrey), the woman her gruesome husband’s son marries who confronts generational abuse in ways Celie can’t, to her husband’s mistress Shug Avery (Margaret Avery), a free-spirited burlesque dancer and singer with joie de vivre to burn.

But Celie, as played by Goldberg, isn’t merely watching: She’s drinking it all in, building up the strength to flee her dreary life. The first time she sees Shug perform, a glimpse at life lived spreads in Celie’s view, Goldberg conveying it with watchful eyes and a widening grin.“The Color Purple” did not win any of the seven Oscars it was up for in 1986, though Goldberg achieved her first Best Actress nomination before winning Best Supporting Actress in 1991 for a showier, more accessible performance in “Ghost.”

In a breakout dramatic performance long before she turned to comedic ones, Goldberg plays Celie as prevailing and always in search of inner truth. Celie has little to smile about amid an abject life of poverty and incestuous abuse, but when Goldberg does, it brightens the whole film. It’s striking to stack “The Color Purple” up against Goldberg’s comic work in something like “Sister Act” or the more broad strokes of “Ghost.” (Though there are certainly funny bright spots in “The Color Purple,” like when Shug dresses Celie up in a sparkly red dress she’s even more uncomfortable in than her own skin.) It’s a remarkable, primarily silent performance that reflects an inner working machine, both in Celie but also in Goldberg, building emotion out of observation and an acting tour de force out of few words. —RL

-

Richard E. Grant as Withnail in “Withnail and I” (1987)

Image Credit: ©Cineplex-Odeon Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection Is there a better example of drunk acting than Richard E. Grant’s turn as the indelible Withnail? Perhaps, but there’s arguably none more flamboyant. An unemployed actor living with the more reasonable “I” (Paul McGann) in a flat so dirty that merely attempting to clean the kitchen can cause severe existential distress, Withnail drowns his professional and personal sorrows in booze of all stripes, up to and including lighter fluid. That Grant, a teetotaler with a severe alcohol allergy, rendered the colorful, self-pitying intoxication of Withnail believable is one thing, but to make him endearing in spite of his childish decadence is another entirely.

A posh fuck-up estranged from his wealthy family, Withnail has plenty in common with elite failsons who trudge from one drunken crisis to a next. However, Withnail appeals because his larger-than-life personality isn’t in service of money or power. He doesn’t want to run a company. He merely wants to play the Dane and hang out in pubs.

Set in the fall of 1969, Bruce Robinson’s “Withnail and I” chronicles the hangover of the Swinging Sixties, as Withnail, “I,” and their drug dealer compatriot Danny (Ralph Brown) struggle to hang onto bohemia even as they know it’s already over. (“They’re selling hippie wigs in Woolworths, man,” Danny muses while stoned.) While “I” finds a life raft out of the flat by accepting an acting job that would take him to Manchester, Withnail remains stuck with a permanent buzz.

Granted, Withnail is an inveterate liar and coward, but Grant sells Withnail’s spinelessness with remarkable charm; you buy his apologies even when he willingly throws “I” into a compromising sexual situation with his predatory Uncle Monty (Richard Griffiths). Yet, Grant also sells the tragedy of someone forever doomed to recite Hamlet alone in the rain until he can demand some booze once again. —VM

-

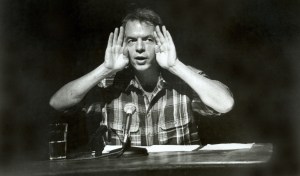

Spalding Gray as Spalding Gray in “Swimming to Cambodia” (1987)

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection A glass of water, a microphone, and a notebook, all neatly laid out on a plain table. These are the few physical tools monologist Spalding Gray has at his disposal in Jonathan Demme’s “Swimming to Cambodia.” The rest comes from the timbre of his voice as he free-associates between multiple topics that span from New York to Southeast Asia. These include his experience filming a small role in Roland Joffé’s “The Killing Fields,” the political history of Cambodia from Operation Breakfast through the genocide at the hands of the Khmer Rouge, his frustrations with his loud upstairs neighbor, and his search for what he describes as “a perfect moment.” It’s a testament to Gray’s writing that he collates these disparate ideas without them seeming incoherent, but it’s his performance as a man sitting alone on a stage that gives them life.

The original theater performance of “Swimming to Cambodia” was over four hours long and spanned two nights; for the feature film, Demme condensed Gray’s lengthy piece into 87 minutes. Yet, the precis version of Gray’s show feels heightened by the presence of a camera: the way Gray will cock his head in a close-up or hit a particular syllable of a word in time to a lighting cue stands as a loving collision of cinema and theater. If you’re in tune to his storytelling style, Gray’s various tics become addictive: the way he amplifies his voice or quickens his pace to generate tension, how he lets a punchline land by simply waiting until it has fully sunk in, or the manner in which he smirks, with his eye and his mouth, when he arrives at a clever line.

The gestalt of “Swimming to Cambodia” is about Gray — a privileged WASP artist living in New York — grappling with the presence of evil around the globe and the way it sits neatly next to humanity’s myriad wonders and joys. He decidedly doesn’t resolve the tension or come to any firm conclusions, but watching him tease it out is its own reward. —VM

-

Melanie Griffith as “Lulu” in “Something Wild” (1986)

Image Credit: ©Orion Pictures Corp/Courtesy Everett Collection Inexplicably met with lukewarm feelings upon release, Jonathan Demme’s “Something Wild” may very well go down in history as having one of the best character introductions appreciated by the fewest people.

The deliriously good screwball comedy/road trip romance/crime thriller stars Melanie Griffith in a shape-shifting free-spirit role that at first seems to capitalize on ’80s Hollywood’s very worst, pre-“Working Girl” instincts. And yet, E. Max Frye’s snappy script, Demme’s relentlessly zippy pacing, and Griffith’s undeniable magnetism (those eyes) establish the film’s chameleon-like muse with such fiery finesse you’d almost have to forgive any would-be missteps. That’s with or without the lush character work that does indeed come as first impressions give way to melancholic complexity, and Griffith turns her kaleidoscopic lead into one of the decade’s most interesting fictional women.

As first introduced, “Lulu” is a manic pixie dream girl from before the trope took proper shape: arriving in a jet-black pencil skirt and green heels like chic, self-assigned armor — before diagnosing Jeff Daniels’ check-dodging Charlie as a “closet rebel” and quietly robbing a liquor store offscreen. Griffith slips into that unconventional, cool girl, “fuck you in half” (as Ray Liotta’s villain character would put it) posturing with ease. But when Lulu, real name Audrey, drops the alter ego, it’s the wry crinkle at the corner of Griffith’s mouth matched with the bubbling tears behind her spider-webbed lashes that will make you believe this volatile stranger truly wants something real — if only for a moment. —AF

-

Dexter Gordon as Dale Turner in “Round Midnight” (1986)

Image Credit: Warner Bros. How many great performances does it take for an actor to be consider one of the all-time greats? Jazz saxophonist Dexter Gordon only appeared on screen a few times, but his one lead role put him in the history books when he was nominated for an Oscar for “Round Midnight.” In Bertrand Taverier’s ode to American jazz and the Parisian nightclub culture that embraced it, Gordon plays Dale Turner, a legendary — and legendarily self-destructive — sax player whose best days are behind him when a friendship with a young fan gives him one last burst of vigor before he flames out.

Gordon simultaneously conveys fiery inner passion and devastating physical exhaustion as a man desperately in love with his art who is no longer able to practice it as he once did; the actor is positively heartbreaking in the way that he shows how his character’s alcoholism is both the escape from the brutal reality of his life and the cause of it. Gordon disappears into the role so completely that many observers assumed he was playing himself, but this truly is a great performance — by all reports the real-life Gordon was lively and funny, not weary and anguished, and many of his most idiosyncratic gestures and speech patterns were pure inventions Gordon created specifically for the character. —JH

-

André Gregory and Wallace Shawn as Wally and André in “My Dinner with André” (1981)

Image Credit: New Yorker Films Wallace Shawn and André Gregory have long insisted they aren’t just playing themselves in Louis Malle’s touching two-hander “My Dinner with Andre.” The lifelong friends paired up after playwright Gregory’s stint in Europe staging experimental theater and dabbling in New Age communities (and near-death experiences). Malle got his hands on the script they developed, staging the film over the course of an evening spent in a single New York restaurant.

It’s an evening that Wally (Shawn) is mostly dreading, and who’d blame him? For the film’s first hour, his pal André (Gregory) waxes enlightened about the profundity of his spiritual encounters, barely allowing Wally a chance to sip a glass of water or take a breath. As the evening rolls on, Wally finally grows frustrated over his friend’s mystical mental wanderings and reveries: “Do you want to know my actual response to all this?” The mood changes, and suddenly Shawn’s character is digging into the complacency he feels about his girlfriend, Debbie, and his contentment to a life resigned to a cold cup of coffee that hopefully doesn’t have a dead cockroach in it.

The conversation slowly unfurls the fissures in both their lives as they close down the restaurant and André leaves Wally with a haunting coda: “What does that mean? A wife, a husband, a son? There’s no wife there. A baby holds your hands and then suddenly there’s this huge man lifting you off the ground, and then he’s gone. Where’s that son?”

It’s almost unbelievable that Shawn and Gregory aren’t playing themselves, their rapport so specific and lived-in that they manage to pack an entire life’s worth of friendship into two hours. We can only hope the same for our own relationships, which in reality pale to the real-time understanding these two come to thanks to an inextricable pair of profoundly simpatico performances. —RL

-

Ossie Davis as Da Mayor in “Do the Right Thing” (1989)

Image Credit: ©MCA/Courtesy Everett Collection In a movie full of some of the most iconic performances of the ‘80s, Ossie Davis’s Da Mayor still stands out. In his rumpled seersucker jacket and floppy hat (at times scrunched and slid back like a porkpie), the 70-year-old Davis conjured a portrait of tattered humanity. Da Mayor doesn’t have a lot to fill his days: He doesn’t have much money — thank God those Bed-Stuy rents were low then — nor discernible family. The highlight of his day is getting his cold Miller High Life from the grocery.

It’s a testament to Davis’s expansive empathy that he could play a character living this quiet of a life, someone so important despite no particular accomplishments credited to his name, when Davis himself had been such a polymath: playwright, director, theater actor par excellence, as well as a civil rights activist who literally gave the eulogy at Malcolm X’s funeral.

Of course, Da Mayor had to be the moral center of the movie: not someone unquestionably good by any means — who is? — but good enough to deliver the title as a line of dialogue, some advice for Spike Lee’s own Mookie. But yes, he is flawed, even getting a little racist with the Korean owners of the local grocery when they suddenly don’t carry Miller High Life. “Alright. Alright,” he huffs. “But you’re asking a lot to make a man change his beer. You asking a lot, doctor!”

That’s right, he calls everyone “doctor” and usually speaks of himself in the third person, culminating in his first big sparring match with Mother Sister (Ruby Dee, Davis’ wife in real life). They have a love-hate thing going on. Mostly hate, as she doesn’t want him drinking in front of her stoop, while she seems permanently confined to sitting in her window sill. But when he rescues a child from a speeding car and she shows interest, Lee stages an incredible visual joke for Da Mayor: at the moment he turns to speak with her, his hope newly kindled, the street lamp above his head flashes on like a “Eureka!” lightbulb. You couldn’t be happier for him then, this Saint of People with Crumbs on their Jacket Lapels. —CB

-

Wendell B. Harris Jr. as William Douglas Street in “Chameleon Street” (1989)

Image Credit: Wendell B. Harris Jr. To watch Wendell B. Harris Jr.’s wily, sardonic turn as Black con artist William Douglas Street in “Chameleon Street” — a film he also wrote, directed, and edited — is to bemoan how few other performances he’s given in his career. (Two bit roles in “Out of Sight” and “Road Trip,” to be exact.) A remarkable debut feature that should have led to bigger and better things, “Chameleon Street” chronicles the life and crimes of Street, a haughty autodidact who allegedly, successfully impersonated a journalist, a lawyer, an exchange student at Yale, and most astounding, a surgery internist who helped perform multiple successful hysterectomies.

Though Harris’ feverish, yet controlled direction as well as his wittily urbane script are obviously essential to “Chameleon Street,” it’s his supercilious performance as Street that makes a profound impression. He embodies the con man with an earned sense of superiority — someone who’s genuinely canny and well-read enough to be the smartest person in almost every room he enters, especially those filled with white, aged Ivy Leaguers — yet still a victim to status obsession America has conditioned everyone to chase.

As the anti-heroic Street, Harris never requests sympathy from audiences, especially with regards to his womanizing, but his dry performance illustrates the understandable lengths a Black man in America will go to earn the respect (and compensation) he deserves. Street would rather dress down a boorish racist at a bar for using poor grammar and field a punch from him in return than raise his own hands because he knows words are his chosen weapon. Through clipped delivery and judgmental gaze, Harris-as-Street communicates he belongs in spaces where rhetoric, intellect, and savoir faire reign supreme, even if he doesn’t have the credentials to back it up. —VM

-

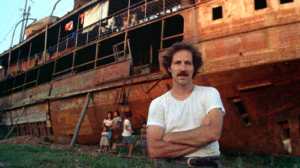

Werner Herzog as Werner Herzog in “Burden of Dreams” (1982)

Image Credit: Flower Films Without implying that Werner Herzog was effectively “doing it for the ’gram” — that he spent four years trying to pull a 320-ton steamship over a hill deep within the Amazon jungle just because that kind of Sisyphean folly served his personal legend as the world’s most fiercely committed filmmaker — it’s still fair to say that such a consummate showman knew what he was doing when he invited Les Blank to capture his suffering on camera. Herzog was, of course, more preoccupied with “Fitzcarraldo” than he was with “Burden of Dreams,” but if Klaus Kinski is going to strangle you to death a few hundred miles away from civilization, it couldn’t hurt to have an observational documentary filmmaker standing nearby.

To watch “Burden of Dreams” is not just to see a director undaunted by the kind of challenges that would send most of his peers running for the hills, but also to see a director who relishes in his suffering; who rues the fact that he was born into a fully explored world, and dedicated his life as an artist towards tasting a morsel of the mad adventure that has driven so many of his characters, fictional or otherwise, to the ends of the earth. Just because Herzog has earned his myth doesn’t mean that he hasn’t been happy to perpetuate it himself (“We are gonna take advantage of this myth,” Fitzcarraldo says when the indigenous people confuse the foreigner as a white god of prophecy), and his performance in “Burden of Dreams” is nothing if not the deadpan comic turn of someone who’s always been both the artist and subject of everything he makes.

Scripted or not, there may be no line delivery in the ’80s as stirring, irony-free, or well-rehearsed as when Herzog stares into Blank’s camera and intones that if he were to abandon this project he “would be a man without dreams.” Maybe Herzog is exactly the same way when the cameras aren’t rolling, but after seeing “Burden of Dreams,” you’ll never quite know for sure. —DE

-

Dennis Hopper as Frank Booth in “Blue Velvet” (1986)

Image Credit: ©De Laurentiis Group/Courtesy Everett Collection “Heineken? Fuck that shit. Pabst. Blue. Ribbon.”

Dennis Hopper’s Frank Booth is among the most evil creations in all of movies, endlessly quotable despite being a misogynistic, alcoholic, gas-inhaling gangster who tortures Isabella Rossellini’s tragic Dorothy Valens while exposing Kyle MacLachlan’s sheltered Jeffrey Beaumont to the awful ways of the world. He wields Frank’s demonic nature with a straight-faced glee unlike anything the movies have given sense, his face alone becoming as nightmarish as any of the imagery that David Lynch has given to the world since. —RL

-

Holly Hunter as Jane Craig in “Broadcast News” (1987)

Image Credit: ©20thCentFox/Courtesy Everett Collection Who isn’t firing on all cylinders in James L. Brooks’ 1987 Best Picture nominee? Brooks’ classic genre-bender — it’s a rom-com, it’s a workplace drama, it’s both! — is a true three-hander, toggling back and forth (and forth?) between three very different news junkies as they love and work their way through, well, quite a bit. But everything really hinges on Holly Hunter’s Jane Craig, the emotional center of the film and the most talented of the broadcast trio. Like many women in male-dominated fields, Jane has to work twice as hard to even be considered in the same league as straitlaced anchor Tom (William Hurt) and his brash would-be successor Aaron (Albert Brooks), and it’s her passion that both makes and breaks her.

Hunter deftly handles the many facets of Jane, juggling the proverbial balls with what appears to be both ease and total mania (read: pure Jane). For her first Oscar-nominated role, Hunter threads the line between striving career woman and unabashed romantic, and it’s up to the actress to find the ways in which those ideals intersect and, often, threaten to rip Jane cleanly in two. That tension makes for a combustible combination, the seemingly at-odds elements giving balance to Brooks’ multi-faceted feature.

Yes, it’s a three-hander, but none of this works without Hunter’s flinty, fiercely open performance as Jane. While some might smart at the breakdown of both of Jane’s potential romances by the film’s end, Brooks finds the honesty in where she lands: a career woman, carving out her own space, the kind of trailblazer only Hunter could play. —KE

-

John Hurt as John Merrick in “The Elephant Man” (1980)

Image Credit: ©Paramount/Courtesy Everett Collection “I am a human being!” With this heart-rending line, John Hurt — the consummate British character actor — secured his place in the pop-culture pantheon for eternity. His is a rare starring performance as John Merrick, whose physical abnormalities earned him the titular moniker as well as a lifetime of abuse at the hands of his fellow men. That any performance at all could be discerned beneath mounds of facial prosthetics speaks both to Hurt’s gifts of full-body expression and those of makeup designer Christopher Tucker, whose egregious lack of Oscar recognition for recreating Merrick’s severe deformities led to the creation of the Academy Award for Best Makeup and Hairstyling.

Hurt, however, did receive a nomination for Best Actor at the 1981 Academy Awards, and justly so. He was clearly in some kind of flow at the time. Between 1978 and 1983 alone, he appeared in such distinct and acclaimed classics as “Alien,” “Watership Down,” “Heaven’s Gate,” “Midnight Express,” and “History of the World — Part I.” Still, despite his roles in these and literally hundreds of other films and series, Merrick remains Hurt’s most indelible character. Bradley Cooper, who played Merrick in a 2014 Broadway revival, even credited the portrayal with inspiring him to become an actor.

One can still see why four decades later. In a film that could so easily have skewed maudlin, preachy, or false in the wrong hands, director David Lynch pushes Hurt towards sensitivity and grounded realism (a mode of performance Lynch later returned to with similarly stellar results in The Straight Story.) Their Merrick is gentle and sympathetic, for sure, but he is neither saint nor martyr. He simply experiences love and hatred and horniness, righteous anger, petty indignation. He is, as he declares so memorably, simply a person, a fact no actor could have proven better than Hurt. —SM

-

Issiaka Kane as Nianankoro in “Yeelen” (1987)

Image Credit: Souleymane Cissé The Malian actor Issiaka Kane’s one appearance in a movie was a knockout: as Nianankoro, a Bambara youth who leaves home and his mother for the first time to gather worldly experience and prepare for a showdown with his father Soma (Niamanto Sanogo), a sorcerer who wants to keep all knowledge of the magical arts to himself. He fears his son will take some of his knowledge and become a threat to him. Sound familiar? Make “Yeelen” a double feature with “The Empire Strikes Back.”

Kane’s performance of Nianankoro’s “hero’s journey” arc has to condense what Mark Hamill could do over an entire trilogy into just one 105-minute film. He heeds the call to marvelous effect. At the beginning he’s still an uncertain youth, staring blankly ahead when his mother talks to him and warns, “You can’t vie with your father. He is a terror.” This is not a stare of stoic reserve, it’s him being uncomprehending of the enormity of what lays ahead for him.

When he embarks on his journey, he immediately gets caught by the Fula people, who think he’s a thief. Now he has to put his own nascent sorcerer skills to use, after a bit of bluffing saying he could have easily killed them all if he hadn’t been distracted. Well, his sorcery skills pay off: there’s a remarkable moment where magic is conveyed just through acting as Nianankoro “freezes” one of the Fula warriors.

His immaturity is still apparently when, after he’s won the Fula king to his side, he betrays him by sleeping with the king’s wife. His confession cop-out line “My penis betrayed me” is a deferral of responsibility for the ages, but after he’s cast out and allowed to take the Fula king’s wife as his own wife, he continues to season until finally he has his showdown with his father, where he exhibits the solidity and strength we’ve been looking for from him the whole movie. Finally, Nianankoro becomes the mystical warrior we always knew he could be.

What became of Issiaka Kane? It’s hard to know… there is a Linkedin profile for someone with that name which says he’s in the Malian army. But for his one and only film, he embodied the “hero’s journey” as well as any actor ever. —CB

-

Nastassja Kinski and Harry Dean Stanton as Jane and Travis in “Paris, Texas” (1984)

Image Credit: ©20thCentFox/Courtesy Everett Collection German director Wim Wenders played Alexis de Tocqueville with his extraordinary outsider’s vision of the U.S. character. And he brought a distinctly European arthouse flavor to the staging of his emotional masterpiece’s climactic scene, a 20-minute slow-burn conversation between Nastassja Kinski and Harry Dean Stanton that’s one of the great verbal duets in cinema history.

Stanton plays Travis, who’s all but lost his mind as the film begins, wandering Texas ever since he was cast out of the life of his wife and child. His brother, who has been raising Travis’s son, comes to find him and much of the next two hours is Travis getting back his marbles and becoming the father to his son he always should have been. Stanton is haunted but deeply open, like someone discovering life for the first time after a past trauma.

When he finally tracks down his wife, Jane, she’s working in a Houston peep show club. Buying some time with her, he slowly starts recalling the story of their marriage’s dramatic end through the one-way mirror. He turns his back while telling his story, so he doesn’t have the power over Jane to look at her while she can’t look back, and recognition slowly dawns on Kinski’s face as she realizes this is the husband she barely escaped from. Yes, he was monstrous at one time, with only his years of wandering in the desert seeming to have turned him into a gentler, more human individual.

When Kinski is listening to all this she looks down and a tear rolls down her face. She can’t see Travis either, but eventually comes to the window and puts her hands against it hoping to catch a glimpse and reconnect one last time with the relative safety of the barrier between them.

How do you connect without really connecting? Kinski and Stanton are isolated from each other but achieve a level of understanding here that eluded them when they were married, Wenders’ Bergman-like blocking finding ways for them to react to each other without the other seeing. They show, magnificently, that sometimes the key to getting closer is a little distance. —CB

-

Youki Kudoh as Mitsuko in “Mystery Train” (1989)

Image Credit: ©Orion Pictures Corp/Courtesy Everett Collection “Far from Yokohama,” the first of three stories that comprise Jim Jarmusch’s Memphis-set anthology film “Mystery Train,” follows a young Japanese couple on a cultural pilgrimage to the birthplace of rock ‘n’ roll. While the taciturn Jun (Masatoshi Nagase) insists he’s happy in spite of his serious façade, it’s his cheery, Elvis-obsessed girlfriend Mitsuko (Youki Kudoh) who stands as the beating heart of Jarmusch’s fourth feature. Clad in a black leather jacket and sporting an eager smile, not to mention carrying an enormous red suitcase in tow, Kudoh exhibits the infectious energy of someone who isn’t afraid to be a tourist.

In fact, Jarmusch lets her performance serve as the audience’s introduction to the city. As Jun sizes up Memphis with a nitpicking eye and negatively comparing it to Yokohama, Mitsuko takes in every element with enthusiasm. She marvels at every building and neighborhood with delight, and finds a good time at Sun Studio even when she can’t understand the tour guide and would have preferred to go to Graceland.

Kudoh wears every one of Mitsuko’s emotions on her visage: she can’t hide her frustration with Jun’s cryptic, post-coital question about her hairstyle nor her fervent belief that Elvis has a mystical connection to everyone from the Buddha to Madonna. Jarmusch partially characterizes Mitsuko as the embodiment of exported American culture, mainly rock ‘n’ roll and celebrity, and yet Kudoh transcends the character’s symbolism and renders her a person on an exciting journey with their adoring, exasperating partner.

Kudoh’s most crucial moment arrives near the end of “Far from Yokohama” when she literally perks up hearing a gunshot the following morning. Her expression defers any potential danger by being in proximity to violence; instead, she embraces the Americanness of the moment. —VM

-

Jessica Lange as Frances Farmer in “Frances” (1982)

Image Credit: ©Universal/courtesy Everett / Everett Collection Has anyone overcome a more disastrous debut (“King Kong”) with a bigger triumph than Lange’s 1982 one-two punch of “Tootsie” and Frances”? She won her first Oscar that year — as usual, it was the wrong film. Her performance as ill-fated 1930s movie star Frances Farmer is one of the great gifts to cinema. She traces Farmer’s life from an atheistic teenager to a glamour goddess to a brutalized insane asylum inmate, giving as good as she gets with her sparring partner mother (played by no less than Kim Stanley).

The magic trick is that Lange is as exquisitely nuanced in every phase of Farmer’s life. And though the biopic doesn’t skimp on camp absurdities, Lange transcends the script at every turn. Every significant person in Farmer’s life let her down, from the mother who institutionalized her to the lovers and studio execs who tossed her aside. Lange, however, finally restores humanity to the embattled star. —MP

-

Zoë Lund as Thana in “Ms. 45” (1981)

Image Credit: Everett Collection / Everett Collection Zoë Tamerlis (later Zoë Lund) was 17 years old when Abel Ferrara cast her in the title role of his dazzling exploitation masterpiece, a vigilante film that transcends its grindhouse origins thanks to the ferocity of Ferrara’s point of view and the complexities of Lund’s entirely silent performance. As a timid mute garment district worker who transforms herself into an urban avenger after she’s raped twice in the same day, Lund conveys a multitude of emotions with an incredible economy of expression; half the time she barely seems to be doing anything at all, yet by the end of the movie her performance is seared into the moviegoer’s brain, its memory impossible to remove.

Lund spends most of the film being objectified by men and misunderstood by other women, which requires her to thread a tricky needle as an actress: in every scene she has to communicate to the audience what she’s thinking and feeling at the same time that she plays the thoughts and feelings other are projecting onto her. Her transition from mild-mannered wallflower to gun-toting vigilante feels truly organic and heartfelt, not like a crass concession to the subgenre of “Death Wish”-inspired knockoffs populating the 42nd Street theatres of the time; it’s a thrilling, moving performance, and one wishes Lund had been able to give more like it before her too-young death at the age of 37. —JH

-

Genevieve Lemon as Dawn in “Sweetie” (1989)

Image Credit: FilmPac Distribution Before the horrors of the Burbank family unfolded in her “The Power of the Dog,” Jane Campion brought to life the special hell of the familial bond in her feature film debut, about Kay, a woman struggling (and how) with her parents and younger sister, Sweetie. As played by Lemon, Sweetie manages to be both the delight of her parents and the bane of Kay’s existence as she embarks on a tour-de-force of destruction and charm. “Brave” gets trotted out a lot when it comes to performances (often women’s performances), but Lemon’s truly is.

Sweetie is a snarling, infuriating conundrum, one that is slowly crippling Kay emotionally but also seems to alternate between glee and obliviousness as to how her behavior is affecting everyone. And in the film’s climactic sequence, when Sweetie goes completely insane, Lemon manages both pathos and bathos — a difficult combination to nail when one is naked and painted black. —MP

-

Carmen Maura as Pepa in “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown” (1988)

Image Credit: ©Orion Pictures Corp/Courtesy Everett Collection Stylishly clad in a variety of almost exclusively red garments, Pepa, a TV actress agonizing through a tumultuous breakup, evolves from a rageful desperation for her former lover’s phone call to a defiant sense of empowerment over the course of this romp. The intricate personality that Spanish legend Carmen Maura graces the heroine with, elevates her from an ordinary scorned woman to one with a hilariously caustic resolve that’s delicious to watch. Every determined step she takes on her fashionable heels leads her closer to closure.

Early on in her ordeal, Pepa accidentally sets her bed ablaze. Staring into the growing fire, she seems to have a sorrowful epiphany about her self-worth and the falsehoods she’s endured. In that quiet turning point, Maura conveys her character’s emotional disarray with a visage of blankness, as if the new Pepa was emerging from those flames. Later, she cries while laughing, because all the conflicting sentiments that plague her fiercely battle to occupy her face at the same time. She is poised and erratic almost in the same breath.

Slowly, Pepa transcends that initial descent into mental mayhem and takes control not only of her own romantic disgrace, but that of the other women in her periphery, each losing themselves to the drama caused by the men in their lives. “I’m tired of being good,” Maura’s Pepa expresses both as a warning and an affirmation, all while exuding seductiveness.

Though they had been artistic partners on multiple occasions before “Women on the Verge,” this is the first part that Pedro Almodóvar wrote with no one but Maura in mind. The actress embodies both theatricality and earnestness, mimicking the dance between the artificiality of the meticulous arranged sets and the real-world locations on screen, in every flippant quip and glass-shattering outburst, all the way to one final act of enviable fortitude. Drenched in gazpacho and barefoot, Maura’s Pepa risks it all to save the life of the man who’s wounded her so profoundly that he ignited a self-redefining revolution within her. —CA

-

Tatsuya Nakadai in “Ran” (1985)

Image Credit: Toho Movie stars carry the weight of all their accumulated roles with them, so that when you watch their later performances you can’t help but think about what’s come before. Something even beyond art — something existential — happens in the intersection of what the actor’s doing onscreen and your memory of their prior work. That phenomenon is especially palpable watching Tatsuya Nakadai in Akira Kurosawa’s “Ran,” a feudal riff on “King Lear” that frays into the ultimate tragedy about old age and how we all inevitably lose everything.

It’s also the ultimate star part, one in which Nakadai’s magnetism can command the screen as he descends the staircase from a burning castle surrounded by hundreds of extras as bloodthirsty troops. All that going on, and you’re only focused on him.

Nakadai had meaty roles in four previous Kurosawa movies, three of them in which he practically embodied youth. He’s especially memorable in “Yojimbo” as a pistol-wielding psychopath psychotic whose boyish cluelessness has curdled into childish outbursts of violence. He’s all on the surface.

Compare that to his performance in “Ran” 25 years later in a role that practically embodies frailty and disarray. He starts out stolid enough, as the Lord Hidetora Ichimonji, overseeing a boar hunt. When he aims his bow at the charging animal while on horseback himself, his sharp eyes are focused on his quarry like daggers. But a hint of his decline emerges when he falls asleep while at a gathering. Even then, he’s sitting ramrod straight, his head simply slumped forward. The lord’s journey through the rest of the film is a progression from straight lines to curves; when he reunites with his only faithful son after a startling journey, Ichimonji is crouched over in a ball. Now his eyes are unfocused, unlikely seeing anything at all. Few actors have ever conveyed the ravages of age with such physicality (aided by extraordinary makeup), and yet Nakadai was only 50 at the start of filming. How amazing that four decades later one of the actors who best conveyed our unavoidable decay on screen — in this movie, and over the sweep of his extraordinary career — is still with us. —CB

-

Ken Ogata as Yukio Mishima in “Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters” (1985)

Image Credit: ©Warner Bros/Courtesy Everett Collection To take on the role of celebrated yet controversial Japanese novelist Yukio Mishima required substantial courage on Ken Ogata’s part. After all, Mishima was known for sadomasochistic tendencies, homosexual affairs (that were still being denied by his family at the time of production), and his defiant, ritualistic suicide by seppuku after his failed military coup meant to restore power to the Japanese emperor.

Paul Schrader’s film was initially written for a different actor, Ken Takahura, but the part was offered to Ogata after Takahura backed out due to political pressure. Ogata swiftly accepted, brilliantly bringing Mishima and all his polarizing complexities to the screen.

Ogata is one of several actors to play Mishima in the film, depicting the novelist in his later years when he became consumed by an obsession with physical strength and the link between art and action. Mishima believed that the beautiful should die young in order to conserve their beauty before it fades. Here, Ogata’s sinewy physique and severe, focused features almost render him a wax figure. It’s this penchant for precision and perfectionism that Ogata encapsulates so well — the thin line between preserving and annihilating the self. In the film’s final chapter, Ogata’s determined, bloodshot eyes speak volumes as Mishima moves closer to suicide — a tragic, terrifying embodiment of his final artistic statement. —SG

-

Paul Newman as Frank Galvin in “The Verdict” (1982)

Image Credit: ©20thCentFox/Courtesy Everett Collection What the verdict means for lawyer Frank Galvin is less interesting than what “The Verdict” means for star Paul Newman. A late-career triumph, Sidney Lumet’s film is to Newman what “In a Lonely Place” is to Humphrey Bogart: a complete deconstruction of his star persona. Galvin, a hard-up alcoholic attorney who takes on a malpractice suit intended to be settled out of court and insists on doing the right thing, is what happens when life and bad luck catch up to Harper, Hud, and the Hustler.

Galvin’s charm is fraying, and he’s too desperate to feign otherwise. Newman brings a trembling hunger to the role that belies what Galvin sees (correctly) as his last chance. The verdict can’t mean anything more than a stopgap for Galvin in Lumet’s chilly, thrilling movie. “The Verdict” is the capstone to Newman’s career. —MP

-

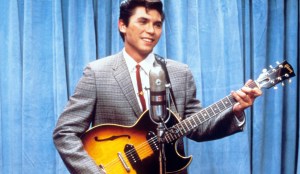

Lou Diamond Phillips as Ritchie Valens in “La Bamba” (1987)

Image Credit: ©Columbia Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection The first time Ricardo Valenzuela, who’d later adopt the stage name Ritchie Valens, performs in Luis Valdez’s biopic is not on stage at a crowded venue, but inside a modest garage. He is there to audition for a place in a band, but the moment he plugs his guitar into a tarnished amp and belts out to a rock n’ roll tune can only compare to watching lighting strike. Even in that impromptu setup, his undeniable talent casts a magnetic force.

That immediate establishment of his striking allure is the result of the exuberant presence that Filipino-American actor Lou Diamond Phillips imbued into his on-screen invocation of the gone-way-too-soon, teenaged Mexican American music star. For his first lead role, which would effectively launch his now prolific career, the charismatic Phillips summoned an ineffable of amalgamation of endearing naïveté, burning intensity, and Valens’ unswerving self-assurance that he would become a star. When asked about choosing Phillips over the countless other people considered for the part, Valdez explained that he could see the young actor’s heart through his eyes, a quality only a few select individuals possess.

Although the voice we hear as Valens’ is actually that of David Hidalgo, one of the founding members of the legendary Chicano rock band Los Lobos, Phillips’ vigorous facial gestures as he mouths the words, create a more than convincing illusion that the timeless singing is coming from him in every performance, whether during the breezy “Come on, Let’s Go” or the heartfelt romantic ballad “Donna.” By the time Phillips’ take on Valens, with that winsome smile and perfect hairdo, finally delivers his rendition of the Mexican folk song “La Bamba,” even though neither the actor nor the real-life figure he is portraying spoke fluent Spanish, both of their artistic spirits seem to have completely merged. —CA

-

Marie Riviere as Delphine in “The Green Ray” (1986)

Image Credit: Les Films du losange The hardest thing of all can be to know one’s own mind. Not just “What will make me happy?” but “Is what I think is going to make me happy really going to make me happy?” And of course that question at the root of so much misery that’s never really asked: “Do I actually want to be happy?” Marie Riviere’s Delphine embodies these questions singularly well in Eric Rohmer’s film about the unique stress of conforming to the expectations for being happy while on a beach vacation.

Delphine alternates between being very precise about what she doesn’t want (an extended monologue to her meat-eating friends about why being a vegetarian is better is about the most extreme plunge into cringe comedy a French New Wave veteran ever attempted) while not seeming to know at all what she does want. That means she can be extremely passive when she’s not being picky: “You’re like a plant” one of her fellow holiday-goers says to her, which is definitely not a compliment. All Delphine can do is be awkward, it seems: “Look! You’re destroying nature,” she says to friends who have gone out to pick flowers.

Throughout it all, Riviere maintains a composed, if faltering, exterior to present to the world while her very obvious inner turmoil threatens to peek out. Rohmer had Riviere improvisationally compose her own dialogue for Delphine and she receives a writing credit on the film. She conveys that the goal for Delphine, as for all of us, is for our external self and our internal self to meet, and Delphine’s heart does seem to quicken at the prospect of seeing “the green ray,” the last flash of green from the sun’s disk as it sets — a sight rare enough that the legend goes that if you see it, you can at last understand yourself. Decades since the film’s release, Riviere has said that she still has not seen that actual last flash of green at sunset in real life herself. It’s that rare.

But she immortalized the fable of it, the legend of it, for all who yearn for that day when no gulf exists between who we are and who we think we are. —CB

-

Meg Ryan as Sally Albright in “When Harry Met Sally” (1989)

Image Credit: ©Columbia Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection When we first meet Sally Albright in Rob Reiner’s enduring 1989 rom-com gem, she’s just about to start her life, her real life, her post-college life, as she heads off to the big, bad city with… some strange man (Billy Crystal) in tow. As is so often the case with the pivotal moments in our lives, it’s impossible for Sally — but not us, this is, after all, a film entitled “When Harry Met Sally,” and here we are watching Harry meet Sally — to recognize the gravity of the moment. She will.

Ryan’s rom-com bonafides are not — nor have they ever been — up for debate. Her bubbly laugh, uncanny ability to turn on her sad eyes at the seeming drop of a hat (or heart), and every-gal charm recommend every genre picture Ryan has picked to star in (and her run of “When Harry Met Sally” into “Sleepless in Seattle” into “You’ve Got Mail” is unimpeachable). But Reiner’s film is perhaps the keystone of Ryan’s prodigious romantic and comedic talents. Her Sally is a real person, full and fallible and ever-changing, and the work Ryan put into the character is clear as each chapter of the film, all of them years apart, unfold. We see her evolve and change, sure, but her heart remains, and that’s all Ryan.

Mostly, we watch Crystal’s Harry Burns try to catch up with Sally — so obviously his soul mate, so clearly the more evolved of the two — as they fight and love through years and years of fraught friendship. Ryan’s Sally might be most widely remembered for her iconic “I’ll have what she’s having” deli-set faux-orgasm, but tucked into Reiner’s film are also moments of acute heartbreak that Ryan just as strongly sells. Look no further than the moment she realizes that Harry has finally realized what’s been under his nose, as the sparkles of an New Year’s Eve celebration alight behind her, and Ryan’s face moves from heartbreak to disbelief to pure joy. You can’t teach that. —KE

-

Fernando Ramos da Silva as Pixote in “Pixote” (1980)

Image Credit: Embrafilme It starts with that face. Both older than his years and still unmistakably young, Fernando Ramos da Silva holds all of “Pixote,” Hector Bacenco harrowing tale of disenfranchised Brazilian kids, in his striking facial features. Eyes both wide open but clearly tired, a mouth that’s as quick to curse as it is to offer an almost innocent smile.

As the film’s namesake character, he brings a lot of himself. Like all child actors Babenco cast for “Pixote,” da Silva came from a challenging social background, and his awful death at the hands of police not even a decade after his breakout success would also become an eerie reminder of the life he portrayed on screen.

But da Silva is not merely playing himself. He is harnessing all he shares with the role and deploying it in a precise manner. He starts out quiet, carefully scanning his surroundings as Pixote is taken to a youth camp, and eventually opens up as the character espaces back into the streets. When he does, da Silva’s performance becomes heartbreaking. Inside, the seriousness found in that memorable face matched Babenco’s creation of a brutal and unforgiving world, and we nearly forget the boy’s age.

Outside, however, in a world just as tough, da Silva helps us remember that Pixote is, in fact, a kid. He’s joyful, silly and needs a mom, but he’s also been thrown into a cycle of crime and addiction. Suddenly, his laugh seems like the last glimpses of a lost childhood. —GJ

-

Gena Rowlands as Sarah Lawson in “Love Streams” (1984)

Image Credit: ©Cannon Films/Courtesy Everett Collection Released just five years before the noxious combo of alcoholism and his almost penitently prolific work ethic finally killed him, John Cassavetes’ penultimate film cast he and Gena Rowlands — his wife and forever scene partner — as siblings whose lives are in shambles. Rowlands plays soon-to-be single mother Sarah Lawson, a woman fighting to maintain a relationship with her daughter at the same time as she’s fighting to keep a grip on herself (a dual struggle that comes to a head during several divorce court deposition scenes that exemplify the actress’ mastery of a many-layered performance).

There’s something disarming and adorable about her, but she’s also hard-edged, steely, and knowing. She can break you apart with a line like “I’m a very happy person. I have a problem: I love my family” or inspire wincing, uneasy laughs when she tells a luggage handler whom she’s very unhappy with, “I hate you.”

“Love is a string. It’s continuous. It doesn’t stop.” Such lines might feel cheesy and overwrought coming from anyone else, but Rowlands sells them beautifully, fully absorbed in her character in a manner that speaks to the misunderstood heart of method acting: She feels and is this person. It’s not a performance so much as an incantatory possession. —RL

-

Winona Ryder as Veronica Sawyer in “Heathers” (1989)

Image Credit: ©New World Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection The dark heart of Michael Lehmann’s pitch black 1989 debut might be Christian Slater’s murderous J.D., but its twisted soul belongs to Winona Ryder’s Veronica Sawyer, trapped in a hellish clique somewhat of her own making. As outsized as Lehmann’s film can feel (though its outrageousness dissipates a little more every year), Veronica’s basic experience still rings true: she fucking hates her friends, realizing long ago that high school popularity is an embarrassing cage for people who will never accomplish more. And Veronica wants to accomplish, well, if not more, certainly something else.

Ryder’s reign as Hollywood’s ‘80s-era It Girl and avatar of goth-y suburban malaise remains unmatched — “Heathers” and “Beetlejuice” and “Edward Scissorhands” (which was released in 1990 but we’re still counting it), oh my! — and her work in “Heathers” is its ultimate touchstone. Ryder’s ability to portray lovable weirdos hinges on that inherent lovability, and she’s always brought affection and pathos to characters that, in lesser hands, would be easy to cast aside as bitchy freaks with a dark streak.

To accomplish that ask with Veronica, Ryder approaches the character’s dismissive nature with a hearty dose of obvious regret. Veronica used to be a loser, and now she’s popular, but she’s the only one who realizes what she lost in the process, and she misses it mightily. That choice helps propel Veronica through some, pardon our French, deeply weird shit and insanely wacky twists. She’s the only person in this suburban hellscape (save for her former friend Martha) that we actually want to root for, because she’s the only person who realizes the error of her ways. High school sucks. Veronica doesn’t. —KE

-

Julian Sands as George Emerson in “A Room with a View” (1985)

Image Credit: ©Cinecom Pictures/Courtesy Everett Colle / Everett Collection Julian Sands, who died earlier this year at age 65 in a hiking accident, was an actor of extraordinary sensitivity and awareness. It’s his romantic, mercurial turn in his breakout film, “A Room with a View,” that most people will picture immediately when they think of him. Many of the lead male characters in romantic comedies like “A Room with a View” start off as awkward or adversarial — think of the line that appears several times in Howard Hawks movies, “The love impulse in men very frequently reveals itself through conflict” — but Sands’ George Emerson defies all the archetypes.

He’s brooding, but because he’s a deep thinker. Quiet, but because he’s shy. (“I’m on the railways” George simply says of his profession.) He’s coiled, tense, naïve, energetic — and given to unique responses like, in one fluid motion, falling to his knees in a simulation of prayer when accosted by a peddler in a Florentine cathedral. Sands’ George is a character whose inner life emanates from his pores, and it’s not hard to understand why young Englishwoman abroad Lucy Honeychurch would be attracted to him and confounded by him on a tour of Italy given for English travelers. He’ll barely say a word at dinner at the pensione, but the next day climbs a cypress tree overlooking a paradise-like Tuscan field to shout “Beauty! L’Espoir!” That’s him “reciting his creed” and invoking “the eternal Yes” his father says.

That moment, an eruption of unbridled naivety at the world and at nature, is so pure, even if, or especially if, it’s a little goofy. (Imagine something quite that strange happening in almost any other comfort-food, period costume drama with rom-com overtones since.) But all expressions of genuine wonder, to an extent, are. —CB

-

Seret Scott as Sara Rogers in “Losing Ground” (1982)

Image Credit: ©Milestone/Courtesy Everett Collection Just like her character’s student, who eagerly invites her to star in his film project, you can’t help but be charmed by Seret Scott in Kathleen Collins’s “Losing Ground.” This is a film about a woman stepping fully into the spotlight, a position she wasn’t sure she belonged in at first. Sara, a university professor in New York City, is quite comfortable behind the podium of the philosophy classes she teaches. But she hesitates when asked to get in front of the camera.

Scott brings a mix of bashful grace and forthright confidence to Sara’s everyday interactions. She has a full-bodied, fluttering laugh when someone compliments her, and she delivers one-liners like an old-Hollywood movie star. “Can I stand still and hit you at the same time?” she asks her husband Victor (played by actor and filmmaker Bill Gunn). The two are both looking to explore new avenues in their professional practices — Sara is embarking on a project about “ecstatic experience,” while Victor wants to move from abstraction into landscape and portraiture. As Victor refuses to compromise on his quest, taking on a lover in the name of artistic exploration, Sara realizes that she deserves even more of the spotlight than she thought. Soon Sara comes into her own, and Scott’s effervescent energy bubbles up and overflows, morphing into an overpowering electricity that completely blows us away. —SG

-

Sissy Spacek as Loretta Lynn in “Coal Miner’s Daughter” (1980)

Image Credit: ©Universal/Courtesy Everett Collection A funny thing happened in the years since Sissy Spacek won an Oscar for her uncanny recreation of Loretta Lynn: Her eerie vocal imitation of Lynn’s distinctive singing voice is still shocking but seems somewhat less impressive. (Blame it on TikTok impressions.) What remains unchanged is Spacek’s performance, a potent combination of grit and vulnerability that sees the 30-year-old actress playing Lynn from 15 to mid-30s. Hand-picked by Lynn, Spacek intuitively understands the singer’s growth from a shy teen who doesn’t know what “horny” means to a woman capable of standing up to her husband/manager — and getting a hit song out of it.

But Spacek’s never more moving than in Lynn’s onstage breakdown during which she rambles about the pressures of fame before collapsing backstage. To emulate a singing voice is remarkable enough; to also bring to life a fully realized human is a monumental feat. (Plus it prompted Spacek to embark on her own short-lived country music career.) —MP

-

Meryl Streep as Zofia “Sophie” Zawistowski in “Sophie’s Choice” (1982)