July 12, 2023

July 12, 2023

This is the written testimony submitted by ITEP Executive Director Amy Hanauer to the Senate Budget Committee’s hearing “Protecting Social Security for All: Making the Wealthy Pay Their Fair Share.”

Chairman Whitehouse, ranking member Grassley and members of the committee, thank you for the invitation to testify today. My name is Amy Hanauer, and I am the Executive Director of the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. My organization monitors corporate tax avoidance and researches the economic distribution of tax policies. We have a microsimulation model that can determine, for most federal or state tax changes anywhere in the country, who will pay more and who will pay less by income, race, ethnicity, and state of residence.

I will make three major points.

- First: Our tax system raises far too little from those with the most.

- Second: The Medicare and Social Security Fair Share Act would raise needed revenue for Social Security and is extremely well targeted to the very wealthy, raising taxes on just 2 percent of taxpayers.

- Finally: Social Security dramatically reduces poverty and enables older Americans to retire with dignity.

Our tax system raises too little from those with the most.

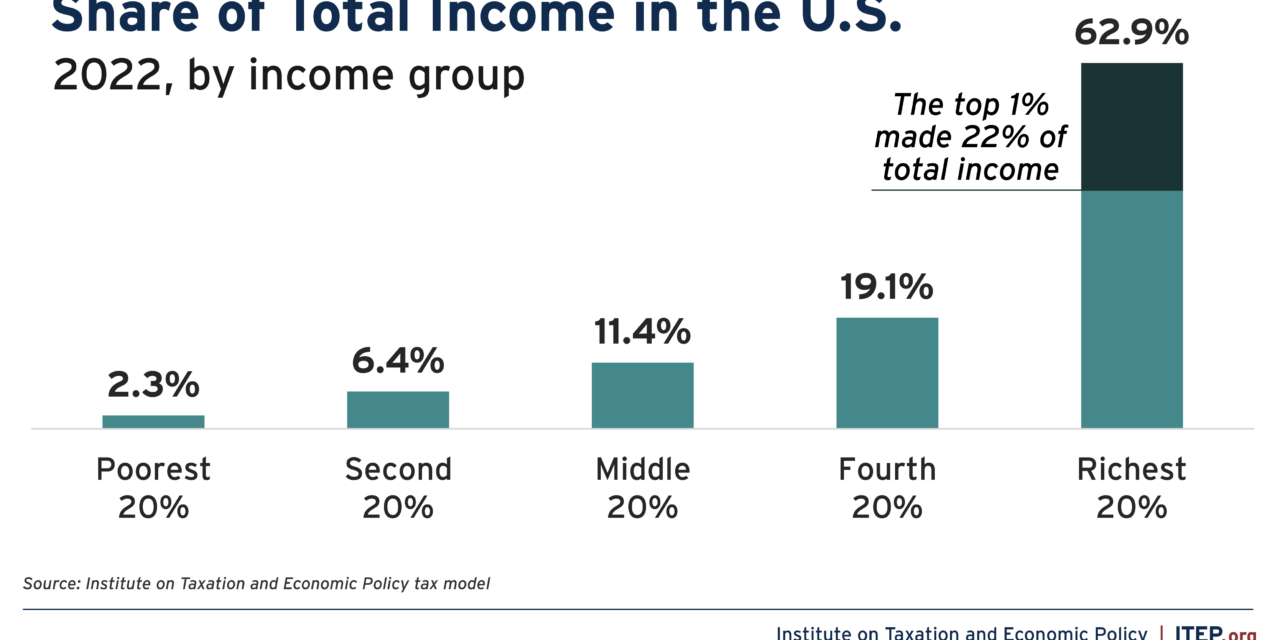

The United States is a very wealthy country, but income and wealth are increasingly concentrated in the hands of a tiny few. Fully 62.9 percent of the nation’s income went to the wealthiest 20 percent of households in 2022. The richest 1 percent alone took in 22 percent of the nation’s income, more than one of every five dollars. And income inequality within that top 1 percent is even greater.

Wealth held by Americans is substantially more unequal than income. Just one quarter of one percent (0.25%) of the population owns a full 30 percent of our nation’s wealth. Over half of the wealth of the ultra-rich is concentrated in just four states: New York, California, Florida and Texas, with the rest scattered among the 46 states which nearly all members of this committee represent.

Despite the overall prosperity of our nation, we fail to deliver many of the basics to keep our families and communities strong. Our tax system is one of the most important policy tools we have for reining in this growing inequality while also raising resources to address our shared needs. We can raise much more from corporations and the wealthy, and we can use that revenue to shore up Social Security, as well as for other priorities. Our economy is possible because of what taxes pay for – from schools, to roads, to financial systems. It is only reasonable that we ask the wealthy people who benefit most from the economy to pay into the society that makes that economy possible.

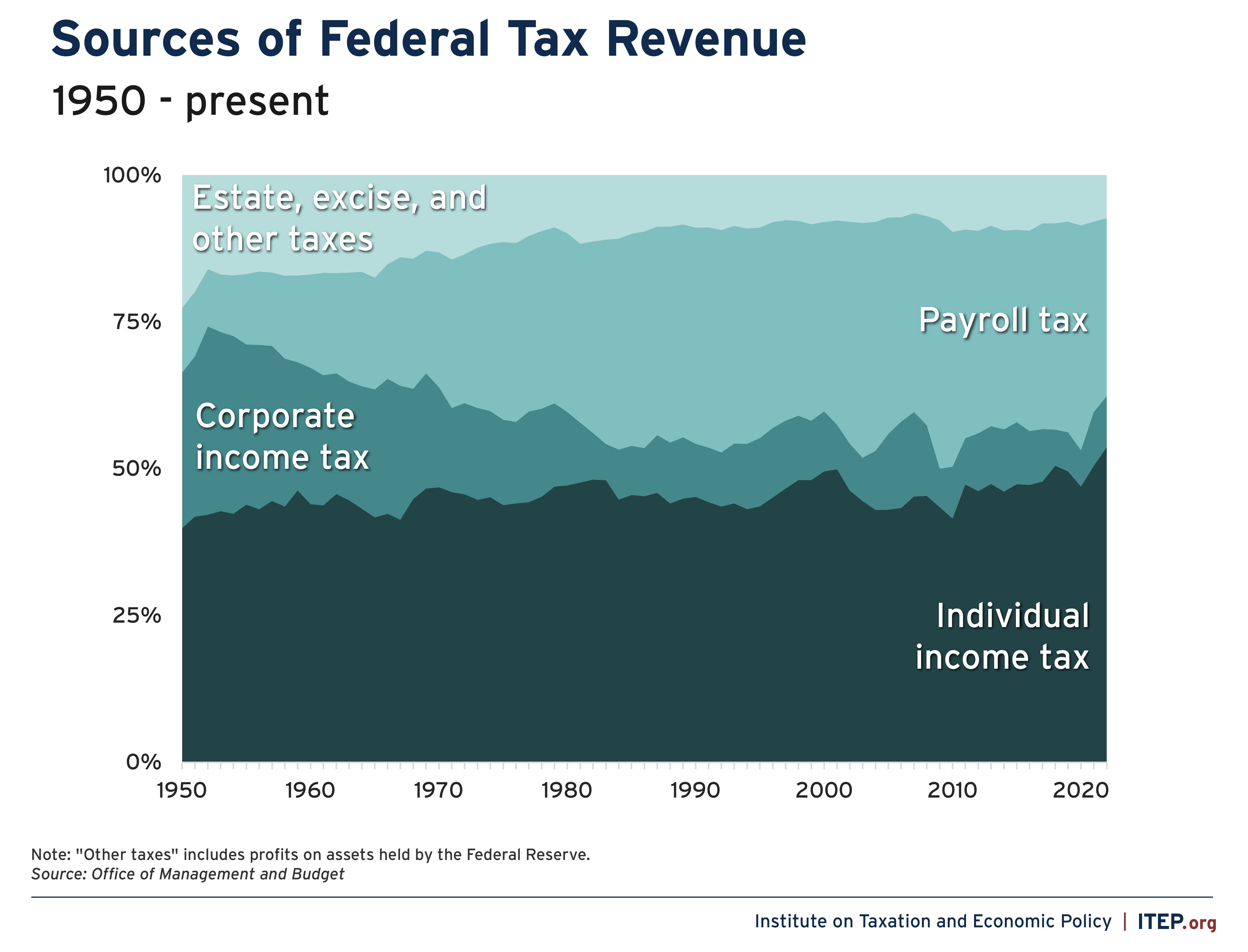

When Social Security was established, corporate taxes were much higher, estate taxes were much stronger, and the top income tax rate was over twice what it is today. Unfortunately, our tax system has grown much less progressive in the years since.

Over recent decades, policymakers cut corporate taxes, estate taxes, and individual income taxes, all in ways that exacerbate inequality and reduce our ability to meet our obligations and stay solvent. We ran surpluses from 1998 to 2001 and the tax code was on course to fully keep pace with rising spending as Baby Boomers retired. But the Bush tax cuts, their bipartisan extensions, and the Trump tax cuts reversed that trajectory and created deficits in every year since. These cuts overwhelmingly went to corporations and the wealthiest individuals.

Policymakers cut the corporate tax rate from over 50 percent in the 1950s to 34 percent in the late 1980s to just 21 percent today, following passage of 2017’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Additionally, legislative changes led to a growing share of businesses organizing as pass-through entities which allows them to completely avoid the corporate income tax.

The top individual income tax rate was over 90 percent throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, then stayed at or above 70 percent until 1982 when policymakers cut it to 50 percent. After further cuts, today the top individual income tax rate is 37 percent. Capital gains and stock dividends, which mostly flow to the richest Americans, are taxed at even lower rates.

And policymakers have cut the estate tax dramatically so that today, an heir can inherit $24 million from his parents completely tax free and can be left still more tax-free through clever manipulation of trusts.[1]

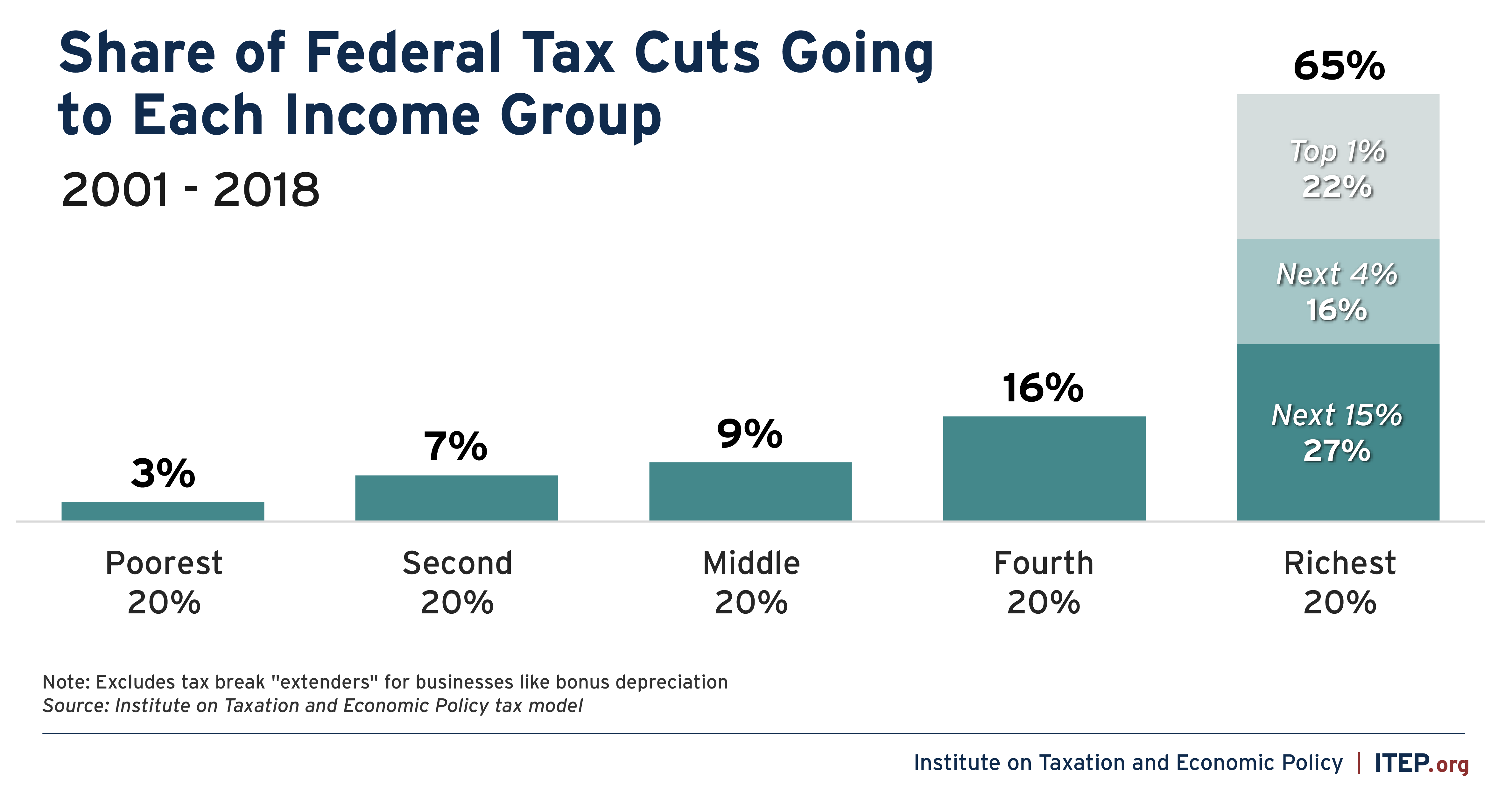

We have estimated that approximately two-thirds of the tax cuts passed between 2000 and 2018 went to the richest 20 percent of Americans and 22 percent went to the richest 1 percent alone. And that is without considering the tidy share that went to foreign investors.

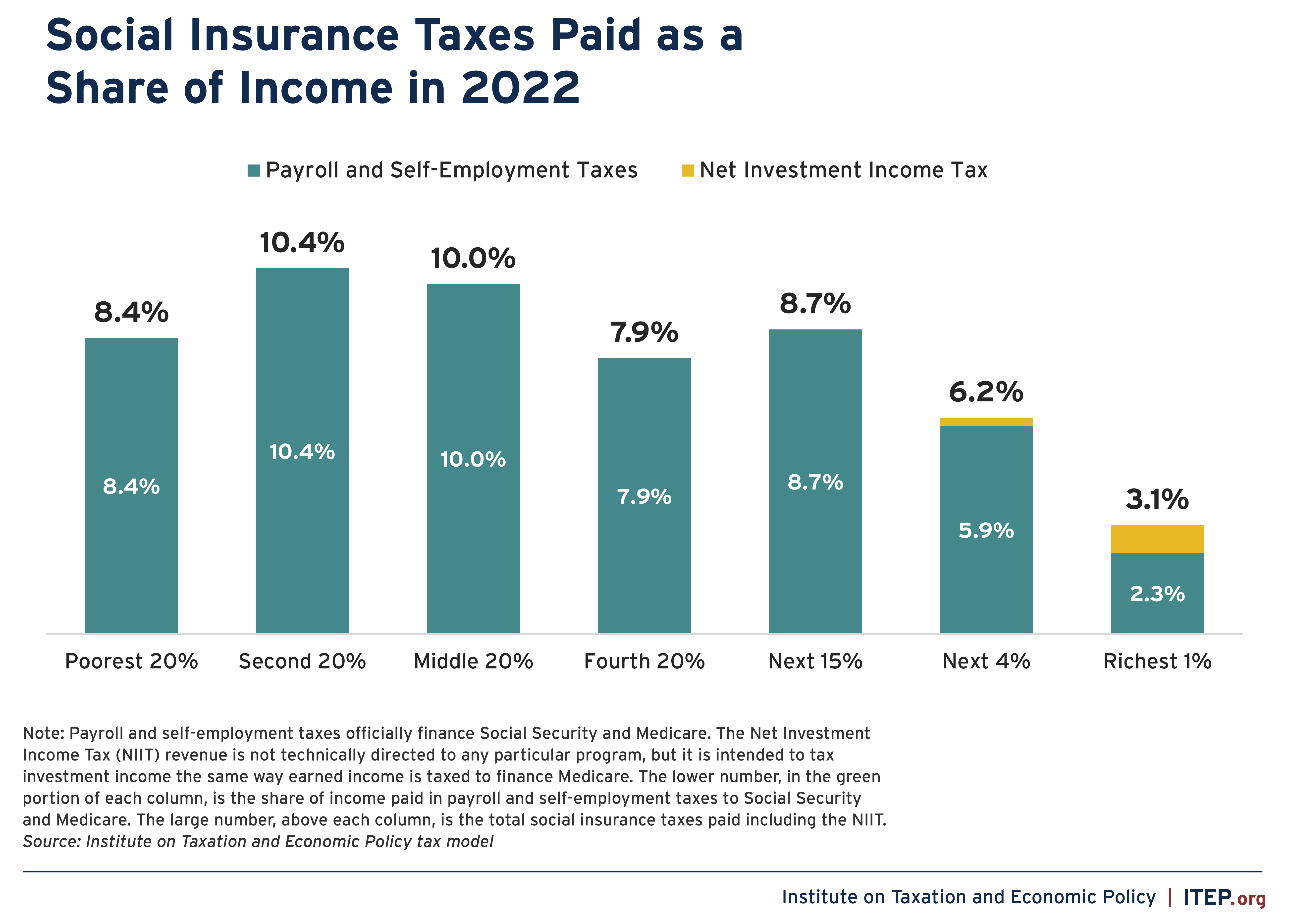

The taxes lawmakers have slashed in recent years are the taxes that fall more heavily on wealthier people and higher earners. Meanwhile, the federal taxes that pay for our most important social insurance programs, Social Security and Medicare, are regressive, meaning they take a larger share of income from low- or middle-income families than they do from high-income families.

This is especially true of the Social Security tax because it only applies to earnings up to a cap and completely exempts the unearned investment income of the well-off. The taxes that finance Medicare are more progressive – they apply to all earnings, without a cap, and effectively have two rates, 2.9 percent for most people and 3.8 percent for high-earners. Well-off people also pay a Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) of 3.8 percent. The NIIT is not technically directed to any particular program but can be thought of as a social insurance tax because it was intended to ensure that well-off people pay a tax on their investment income just as they pay on their earned income to support Medicare.

But the more progressive elements of the social insurance taxes for Medicare are outweighed by the regressive elements of the much larger Social Security tax. In 2022 the poorest 20 percent of Americans paid 8.4 percent of their income toward taxes for Social Security and Medicare taxes combined. The richest 1 percent paid just 2.3 percent of their income in earnings taxes for Social Security and Medicare, with that number rising to only 3.1 percent of their income in social insurance taxes if the NIIT is included.[2]

Social Security taxes have increased over time for middle-income workers. Tax rates for Social Security and Medicare combined rose steadily from 1937 to 1990 from 1 percent to 7.65 percent each on employees and employers. So while policymakers have deeply cut corporate tax rates, personal income tax rates, and the estate tax – all of which fall more heavily on wealthier households – they’ve raised Social Security taxes, which fall more heavily on low- and middle-income families.

Further, even Social Security taxes have become more regressive by exempting more of the income of top earners. The last time Congress made major reforms to Social Security, in 1983, the cap covered 90 percent of all wage income, with only 10 percent above the cap. But because wage growth for top earners continues to outpace wage growth for everyone else, a growing share of total earnings is spilling over the cap and escaping taxation. This rising inequality has nearly doubled the share of wage income above the cap, to about 17 percent. The Economic Policy Institute estimates that income exceeding the cap due to rising inequality has cost Social Security over $1.4 trillion. In addition to high wage income escaping the tax, unearned investment, which is heavily concentrated with the well-off and has grown, is completely excluded.

Because of the cuts to progressive taxes and the increases in payroll tax rates, the payroll tax makes up a much larger share of federal revenue than it did in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, while corporate income taxes and estate taxes comprise a much smaller share. That means that an increasing portion of our government is being funded by a regressive tax.

It is vital that this country starts to adequately tax its very wealthiest. America’s ability to meet our financial obligations and invest in our greatest resource, our people, has been significantly compromised by repeated tax cuts that have mostly benefited the nation’s most privileged. It is time to undo the damage being done to our social and economic fabric from this extreme concentration of wealth.

Taxation of the wealthy is a critical policy tool to address the unsustainable path of ever more of our collective wealth being hoarded by an ever-tinier elite, which pays a smaller and smaller share of taxes.

The Medicare and Social Security Fair Share Act would raise revenue in a progressive way.

The Medicare and Social Security Fair Share Act introduced by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse would reform the taxes that Americans pay to finance these two important programs, by ensuring the richest Americans pay these taxes on most of their income the way that middle-class taxpayers already do. In preparation for this hearing, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy completed a paper analyzing the distributional implications of the proposal, which can be found here. The following section is drawn from that analysis.

The Medicare and Social Security Fair Share Act would address the mismatch between what middle- and low-income households pay in Medicare and Social Security taxes and what the wealthy pay in several ways.

- The 12.4 percent tax that funds Social Security would expand to now cover most employment earnings of the rich – both the amount below the current cap and earnings exceeding $400,000.[3],[4]

- The “additional Medicare tax,” which effectively creates a top rate of 3.8 percent on earnings to fund Medicare, would have a new bracket to effectively create a top rate of 5 percent.

- The 12.4 percent Social Security tax would also apply to self-employment income as would the increase in the “additional Medicare tax” on earnings.

- The Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT), which has a rate of 3.8 percent and is meant to ensure that well-off Americans pay taxes on their investment income to finance Medicare at the same rate as is paid on earned income, would be increased to 17.4 percent for married couples with AGI exceeding $500,000 and other taxpayers with AGI exceeding $400,000.[5] This would ensure that the richest Americans are paying a tax on their investment income to finance both programs at the same rate as is paid on their earned income. (For earned income, the 12.4 percent Social Security tax and the 5 percent Medicare tax would come to 17.4 percent.)

- Finally, the bill would close a loophole in the Medicare taxes that currently allows certain income to escape all Medicare taxes, popularly known as the Gingrich-Edwards loophole after former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich and former Senator John Edwards, both of whom used this loophole to earn millions tax-free. President Biden has included this proposal in his budget plans.

The distributional effects of the changes are provided in the table below. The bill would raise taxes on just 2 percent of Americans. Virtually no one outside of the richest 5 percent of taxpayers would pay more under the proposal and 93 percent of the total tax increase would be paid by the richest 1 percent (households with an average annual income of over $2.5 million a year).

All the Act’s provisions are extremely well-targeted to the wealthiest people in the country. Given the growth in inequality in the U.S., and the degree to which our tax system has asked less of those with the most, this approach makes sense.

Social Security enables older Americans to retire with dignity.

Social Security has been a major triumph of American public policy. The program is the most important part of our social contract and represents a promise we’ve made to America’s working families – that you will pay in and in return you will be supported with dignity in retirement, that your family will be cared for if you die early, and that you will be supported if you become unable to work because of disability.

After policymakers established Social Security, elderly Americans, many of whom were destitute at the time, went from being the most likely age group to be in poverty to the least likely. It lifts more people above the poverty line than any other U.S. program, and without it 21.7 million more Americans would be below the poverty line. Fully 97 percent of older Americans receive Social Security at some point.

Without Social Security, 38 percent of elderly Americans would be in poverty, instead of the 10 percent who are. And for residents of certain states, including Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, and West Virginia, nearly half of elderly residents would be in poverty absent this program. In both Florida and California, Social Security lifts more than 1.36 million people out of poverty

Due in part to discrimination and other structural problems in our labor market and society, Social Security is particularly important for reducing poverty for retired women and for Black and Latino retirees. Women are paid less, are less likely to have pensions, have greater unpaid care responsibilities, and live longer, making Social Security income especially essential for them. The same goes for Black and Latino workers who are paid less on average. Black and Latino retirees would have poverty rates of 50 percent and 45 percent without Social Security. Across all races, it is the largest source of income for the elderly, providing the majority of income for four in 10 retirees and 90 percent of income for one in seven retirees.

Social Security benefits are quite progressive, making them a crucial tool to reduce inequality and prevent poverty. Low- and middle-income workers receive much higher annual Social Security benefits relative to what they paid in than do higher-income workers. Low earners (earning less than 45 percent of the average wage) receive a lower amount ($14,824) but a larger share (about half of their prior earnings), while high earners (earning 160 percent of the average wage) get a higher amount ($32,345) but a lower share (about 30 percent of prior earnings).

As important as the program is for providing dignity and security, Social Security is modest. The average benefit works out to just over $21,000 per year ($21,384). The U.S. ranks just above the bottom third among developed countries in share of average worker earnings replaced. All countries in western Europe except Ireland do better. Denmark, for example, replaces 80 percent of prior earnings while the US replaces less than half that amount. Social Security has a higher retirement age than the public pension programs in the average OECD country even though people live many years longer in all Western European countries.

Social Security can continue to pay 77 percent of scheduled benefits with no revenue reforms, contrary to some claims that the program is on the verge of vanishing. But that is not acceptable. We’ve made a promise to workers that Social Security, modest already, will be at its promised level for them. Reasonable revenue restoration is the way to keep the program robust. This bill delivers that.

Other proposals would weaken Social Security. A recent Republican Study Committee proposal would cut spending on some other social programs, cut taxes in ways that enrich the wealthy, slash enforcement by the IRS to investigate tax cheating by wealthy people and corporations and raise the retirement age for claiming Social Security to 69 years old. This would make our retirement age higher than every peer country except the Netherlands where people live about five years longer and where retirees on average get 89 percent of their wages replaced, compared to 51 percent in the U.S.

These are the two competing visions. In one we do less and less to make America a good place to work and retire, and more and more to increase inequality. In the other, exemplified by the legislation we’re here to discuss today, we make modest reforms to better tax those who are taking a larger share of our wealth and income, in order to reinforce a major pillar of our promise to Americans.

[1] Of course, it is sometimes possible for lawmakers to lower tax rates and still collect more revenue by aggressively eliminating loopholes and special breaks and stepping up enforcement. But this is not what has happened in the U.S. over the past several decades. Researchers have found that effective tax rates of well-off people (what they pay as a share of their income) has dropped over time. See Steve Wamhoff, “Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman’s New Book Reminds Us that Tax Injustice Is a Choice,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, October 15, 2019. https://itep.org/emmanuel-saez-and-gabriel-zucmans-new-book-reminds-us-that-tax-injustice-is-a-choice/

[2] Unpublished estimates from ITEP for 2023. Includes payroll taxes, self-employment taxes, additional Medicare taxes, and the Net Investment Income Tax, which are all the social insurance taxes.

[3] This would leave a “donut hole,” meaning the wages between the existing cap of $170,400 next year and the $400,000 threshold would remain untouched by this tax. However, the donut hole would eventually close because the existing cap of $170,400 is indexed for wage inflation while the $400,000 would not be indexed, meaning the lower cap would keep rising until it eventually surpasses $400,000.

[4] It is not clear how exactly employers would respond to this change but the employer-side payroll tax must either be borne by employers (which would mean employers report smaller profits and thus pay less taxes) or passed on and borne by employees in the form of reduced compensation (which would mean that the taxes employees pay under current law would be reduced somewhat). Because this proposal would make a permanent change in the tax system, this analysis takes the long-term view and assumes that the employer side of the payroll tax would be ultimately borne by employees in the form of reduced compensation. This results in a small decrease in the taxes that apply under current law, like the personal income tax and the “additional Medicare tax” on earnings. But the revenue impact of this reduction in reported earnings is relatively small. This analysis finds that in 2024, the resulting reduction of reported earnings of the rich would cause revenue to fall by $16 billion but the revenue increase from applying the Social Security tax to earnings exceeding $400,000 would generate about $83 billion in new revenue, for a net revenue impact of $66.5 billion in 2024 as shown in Table 2.

[5] Much of the investment income that would be subject to the increased NIIT is capital gains, the profits that investors receive from selling assets for more than they paid to purchase them. Congress’s official revenue estimators at the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and some other analysts assume that wealthy people respond to such changes by selling fewer assets, and therefore “realizing” fewer capital gains, which in turn can dramatically reduce the revenue increase that would otherwise result from the higher tax on capital gains. For further detail see the methodological footnotes in ITEP’s paper prepared for this hearing: https://itep.org/fair-share-act-would-strengthen-medicare-and-social-security-taxes/