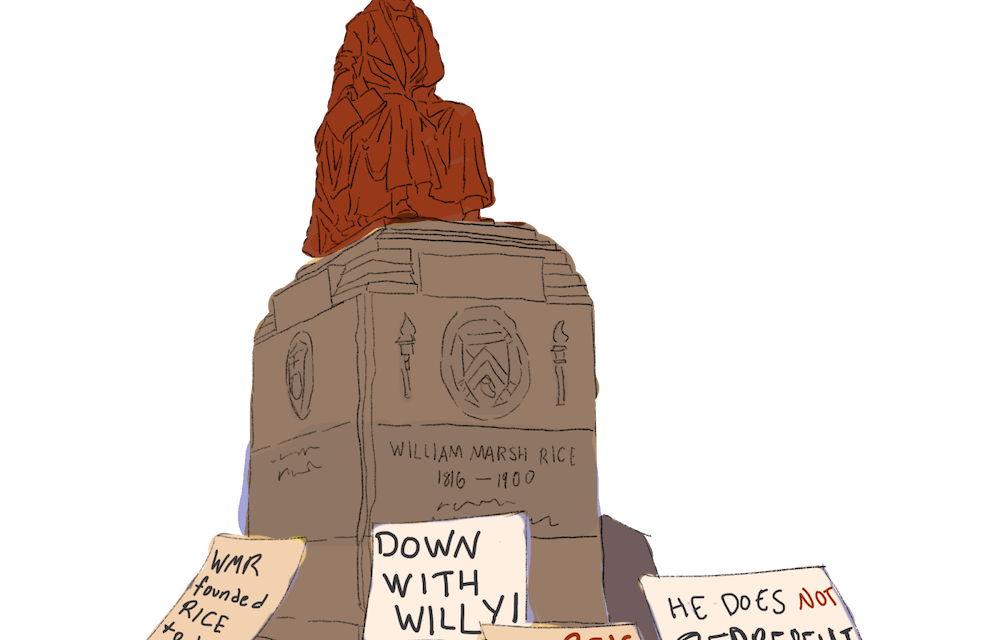

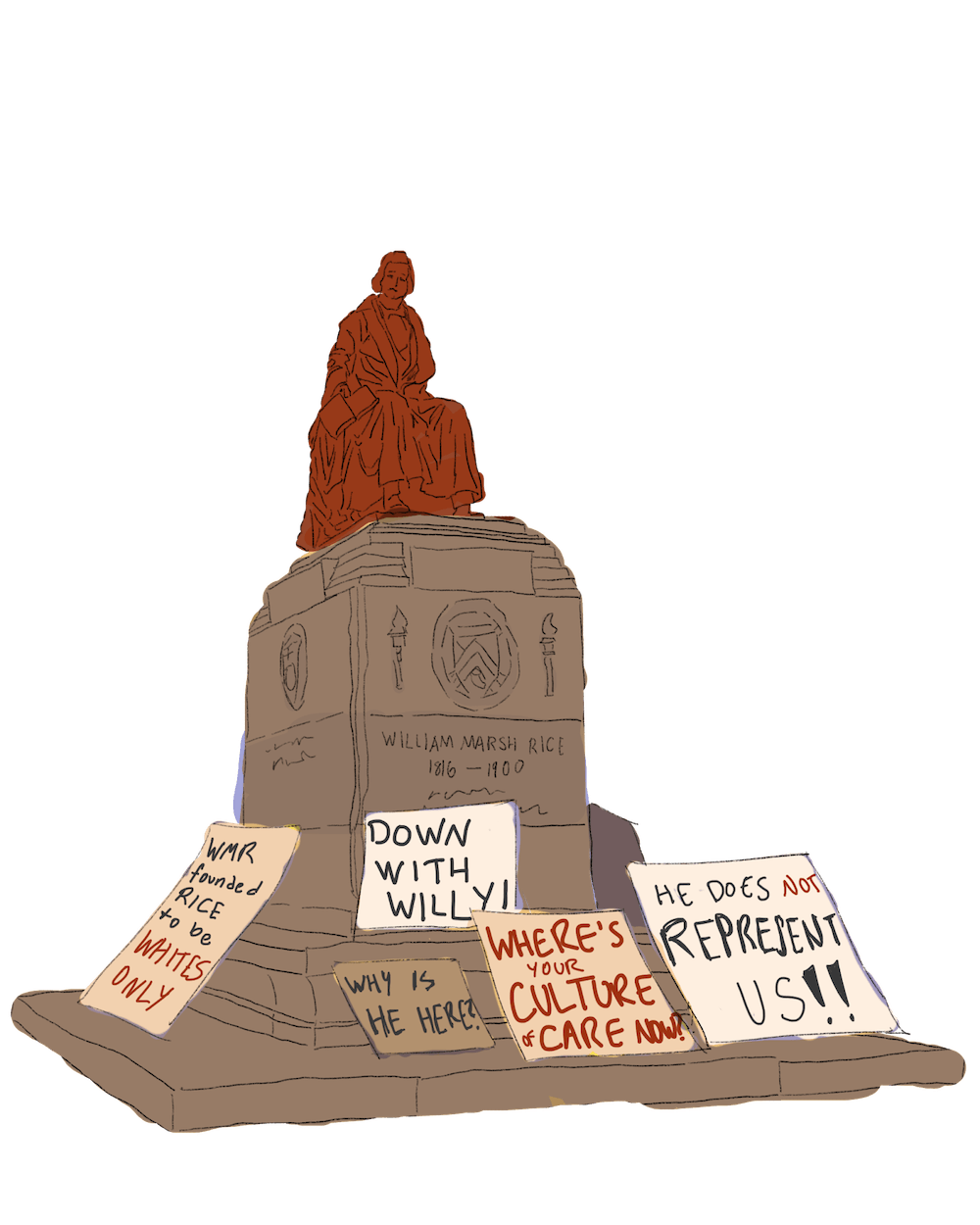

6 to 7 p.m. It was one hour a day, nearly every day, rain or shine, that Shifa Rahman ’22 spent camped outside the Founder’s Memorial statue, often with signs and fellow protestors in tow. “Read the room, Willy,” one sign read.

Rahman began their sit-ins on Aug. 31, 2020, after a summer that had seen massive increases in attention towards racial justice — both on a national level, as George Floyd’s murder sparked a resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, and at Rice.

“As much as we all are in the cause of collective struggle, I realized I can only control what I can control,” Rahman said. “So if I can control being at the statue for an hour a day … I will be able to do that. I have to do that.”

Now, three years later, Willy’s Statue has been removed from its pedestal. It currently sits in storage as the academic quad is closed for construction; the final redesign plan will place Willy on the ground, adjacent to Sewall Hall. The removal comes after several years of discourse around the statue, including sit-ins, Student Association legislation and reports from the Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice.

Though the construction will shut the academic quad through at least April 2024, Rahman said students should consider the bigger picture — and the larger symbolism of Willy’s statue.

“This temporary inconvenience doesn’t compare to the damn near permanent inconvenience of feeling the impacts of systemic racism reflected in the physical art [of campus] daily,” Rahman said. “A measure taken against that should be seen as an ultimate good, rather than just an annoying inconvenience.”

“If you’re concerned about not being able to use the quad because it’s closed off to you, the whole school used to be closed off for Black students,” Milkessa Gaga ’22 added. “We know that this institution wasn’t made with us in mind.”

2016: The presidential election

Today’s Rice is a far cry from the school that students knew seven years ago, some alumni say. The 2016 presidential election was a radicalizing spark for much of the student body, said Summar McGee ’20, who had matriculated shortly before the election.

“Rice used to be considered the most politically apathetic campus,” McGee, who co-founded Rice for Black Life and served as the president of the Rice Black Student Association from 2018 to 2019, said. “This was a whole different university, the university I matriculated into.”

“It wasn’t a bad place … It wasn’t overtly hostile. But it was so microaggressive that it was a hostile environment,” McGee added. “They were spray painting swastikas on campus when I matriculated, and this was commonplace. This was considered Friday behavior … Alum would walk up to you and ask how the women’s basketball team was going, or just assume [that] because you were Black and because you were tall, the only way you could be at Rice was because you played basketball.”

Gabrielle Falcon ’20 said Black students were often forced to champion themselves due to a lack of external support.

“When I was [at Rice], I think Black students felt very isolated and felt very much like they were fighting their own battles,” Falcon said. “I was an [Orientation Week] coordinator and student director, I was a [Chief Justice], I was treasurer of my college. I was very involved in every turn. I felt like I was advocating for Black students. White students don’t have to do that.”

Falcon said that Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 election was the motivation many students needed to jumpstart activist movements. According to her, Black students at Rice became increasingly vocal about issues with diversity and isolation on campus.

“I think when you have a president [who] is marginalizing certain populations in a city that has a plethora of different types of people — and Rice also being a university that is, compared to its peers, relatively diverse — people become more vocal,” Falcon said. “Whenever students at Rice realize that they create the culture around them, they’re unstoppable.”

2019: Task force forms

One year before the Down With Willy movement was born, then-President David Leebron commissioned the Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice to examine Rice’s roots in slavery. The task force was catalyzed by a number of racial reckonings happening at universities across the country, including Rice, at the time.

“Perusing past yearbooks, Rice student Charlie Paul found photos of students performing in blackface, a photo of an African American student captioned as the N-word and a photo from 1922 of ‘the Ku Klux Klan of Rice Institute’ that showed about 20 people, faces hidden, in white robes and hoods,” the Chronicle wrote. “Most of the offensive images were published prior to Rice’s admission of the first black students [in 1964], and the university’s KKK chapter was gone the next year, according to Rice historian Melissa Kean.”

The task force was launched in part to understand and reconcile with this past. In a June 2021 report, it unanimously called for a radical redesign of the academic quad, including the placement of the Founder’s Memorial. In October 2023, it released its final report, a 260-page document examining Rice’s entanglement with slavery and recommending a method of desegregation.

“The way of taking the history of the university most seriously is being open to its consequence in the present,” Alexander Byrd, the vice provost for diversity, equity and inclusion and co-chair of the task force, told the Thresher on Oct. 17, 2023.

Summer 2020: Black students fundraise, list demands

In May 2020, Kendall Vining ‘22 co-founded an organization called Rice for Black Life in the wake of Floyd’s murder. In early June, Rice for Black Life set out to raise $2,500, which they would donate to local advocacy groups. Within 24 hours, they raised just shy of $100,000.

Building on that momentum, Vining and Gaga co-published Tangible Ways to Improve the Black Experience in June 2020. The list of demands included several action items for Rice to “address the systemic policies … that negatively impact Black students in order to move towards Black liberation.” These included better lighting for ID photos, increased diversity training for student leaders, a centralized cultural space for Black students and removing Willy’s statue.

Gaga said he started the list as a personal process. When he observed something he wanted changed, he made note of it. After talking with other students and spurred on, in part, by Floyd’s murder and political attitudes toward racial justice in 2020, he and Vining said they decided to make something more out of it.

“We weren’t going to label it ‘Black students request’ or ‘Black students humbly ask.’ We wanted to use an action verb that was going to spark a conversation and be a headliner,” Vining said.

Fox News picked up Gaga and Vining’s list of demands, publishing an article that, at the time, incorrectly identified Vining as the president of BSA. The list of demands was a “social statement” affiliated with neither the BSA nor the “Down With Willy” social media campaign that began circulating around the same time, Gaga and Vining told the Thresher in June 2020.

That same month, Falcon launched an online petition explicitly calling for Willy’s removal. Falcon said that amid the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, Rice was also learning how to grapple with complex legacies.

“The statue is a great example of a founder of a university. That can’t change. That’s not a reality that does change … but how we interact with him, it could be different,” Falcon said.

Fall 2020: Statue sit-ins commence

On Aug. 31, 2020, Rahman went to the Founder’s Memorial. They had just started to organize the statue sit-ins, and it was the first of what would amount to some 300 days of action.

Rahman said the shockwaves of the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with the murders of Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor, made the summer of 2020 a “very poignant” time for Black students to raise their voices.

At the time, the nation was beginning to turn an increasingly critical eye toward statues. In Rahman’s hometown of Greenville, N.C., a Confederate statue was removed from outside a courtside a few months prior. Even closer to campus, a monument of Confederate commander Dick Dowling was removed from Hermann Park shortly before Juneteenth.

“That also kind of led me to kind of mobilize,” Rahman said. “They could do this in this part of the South, why [couldn’t] they do it at my university?”

“I think that [Rahman] really set an amazing example of keeping the momentum,” Falcon said. “I’m not an activist, I will not take that title. Real activism is what [Rahman] did, which is putting yourself in person, in the line of fire, showing your face.”

Rahman said the student body was largely supportive of the protests, though they sometimes received pushback from passersby and older, predominantly white alumni.

By October, the sit-ins had expanded to include projections, including messages saying “Willy Rice was racist,” onto Lovett Hall and at certain residential colleges such as Lovett College and Will Rice College. An anonymous student who helped organize the projections told the Thresher in October 2020 that they hoped the projections would “[turn] the volume up on the protest.”

Rice University Police Department shut down the projections on Oct. 5, 2020, RUPD Chief Clemente Rodriguez told the Thresher in October 2020. University approval, Bilal Rehman ‘20 said, was always a question organizers grappled with. Rehman was involved in the Down With Willy movement, and also helped organized silent protests for sexual assault advocacy in 2019.

“On the one hand, we were sometimes afraid of the prospect of being punished for organizing urgent and necessary actions on campus, but we also recognized that seeking university approval for a demonstration often slowed us and watered things down,” Rehman wrote to the Thresher.

That same month, the protests began to gain media traction. On Oct. 8, 2020, The Houston Chronicle published a story on Rahman and the sit-ins. On Jan. 25, 2021, The Texas Tribune reported on Texas universities’ hesitancy to part with their Confederate relics.

“The attention was important, we just wanted to continue making the attention for the cause,” Rahman said. “Not just yelling as loud as we can outside the infrastructure, but also within.”

2021: Student Association pushes for change

On Nov. 29, 2021, the Student Association unanimously passed a resolution calling for the university to relocate the Founder’s Memorial. The resolution was introduced by Rahman, and co-written by Sanya Arora and Shivani Gollapudi, then a Duncan College new student representative and the Duncan senator, respectively.

“There was communication between the SA and [Rahman] about drafting a resolution to clarify the students’ perspective regarding the Willy statue to administrators and formalize the SA’s stance on the Down With Willy movement,” Gollapudi, now a senior, said.

The resolution had been introduced to the SA two weeks prior to its passing. Senators then sent surveys to gather student input from their colleges. The majority of students approved. Brown College reported 74% support for the resolution, while Will Rice, Sid Richardson College and Hanszen College reported 70.9%, 67.8% and 62.5% approval, respectively.

Around the same time, campus was also reckoning with the significance of Willy’s Statue. In March 2021, many colleges stopped using the name “Willy Week.” A year later, The Pub at Rice — previously Willy’s Pub — rebranded in solidarity with the Down With Willy movement.

“If you were a voting member and you were directly involved [with the resolution], you were worried. I heard a lot of people worrying about how people were going to treat them, depending on how they voted,” Vining, who served as the Student Association president from 2021-22, said. “I was shocked when there was a unanimous vote.”

After it passed, the resolution was sent to the Faculty Senate, Gollapudi said. Less than two months later, on Jan. 25, 2022, the Board of Trustees announced in an email that the statue would be moved.

“Yes, we did it. But it wasn’t just us,” Vining said. “It’s been years in the making. That is so crucial for students to remember.”

2023: Willy’s final removal

The predominant feeling after the Board of Trustees’ announcement was relief, Vining said, but not everyone was happy.

“I’ve seen some of the older alumni’s reactions to [the redesign] … They’re still pretty pissed off,” Vining said. “I’m not saying we need to destroy [the statue]. I mean, what a waste of resources. If anything, I’m just saying we need to not glorify it. But some of these alumni … they have such a hard-on for that statue.”

Looking forward, students, especially those involved in the protests and activism of 2020, believe this isn’t the end: Rice needs to take further action to disentangle itself from its roots of racism, they say.

“If it’s important to remember the history of William Marsh Rice in relation to the university … then a plaque alone would, in my opinion, suffice,” McGee wrote in a follow-up message to the Thresher. “The statue itself is unnecessary … Rice still, if the statue is indicative, holds on too tightly to its racist past relics in the name of tradition and at the expense [of] progress.”

Rahman calls for prioritizing marginalized students in the redesign plans. Rice may not have been “made with [Black students] in mind,” as Gaga said — but now, Rahman says, that can change.

“In the construction in the academic quad, we should center Black people, we should center Indigenous folks, we should center marginalized folks,” Rahman said. “A lot of the systemic issues we face come [from] barely even taking the chance to be able to be in conversation and engage with one another fully, wholeheartedly enough to understand really where they’re coming from … and particularly knowing what it’s like to be in the margins.”