I first heard Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s work at a reading in a private house in the West Village in 2014. It was a hot and sticky night in New York City, deep in a summer heat wave, and the reading was hosted in a basement apartment packed full of people, eager for relief in beauty. If there was any air-conditioning, it wasn’t a match for the mass of bodies—one of the other readers was Walter Mosley, who’d had the forethought to bring an enormous fan, which he swayed back and forth while we younger, less forethinking writers tried to catch a little bit of his breeze.

But the swelter of the room ceased to exist when Griffiths stood up to read. She explained that her mother had just passed‚ her grief was palpable, and her voice stilled the murmurs that usually accompany a long night of performance. She read a piece about the unease and disquiet of grief, even as she insisted that the mirror between where she stood, living, and the world her mother had moved on to was perhaps more porous, more shifting, than we might think. I was struck, then, by the intense vulnerability of her words and her work—it cut through all the literary posturing of the room that night, to remind me there was more in the world, more at stake in creation, than who sat where on a crowded couch. Griffiths spoke of life, death, the spirit, and the mother, and I remember thinking she was someone I wished to read again and again.

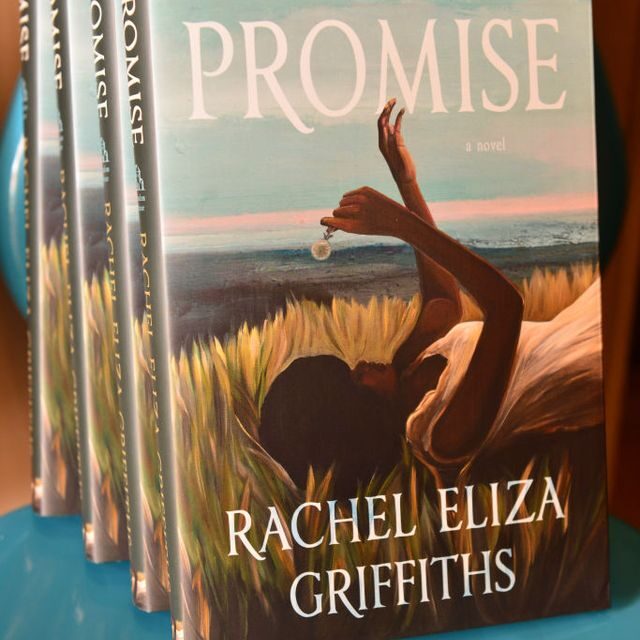

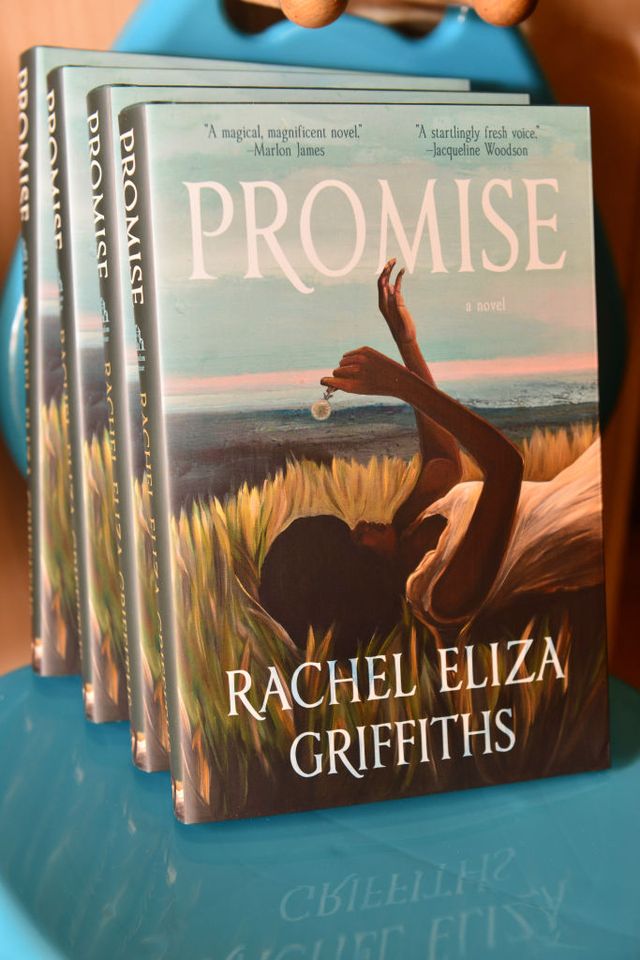

This summer, Griffiths published her first novel, Promise, a luminous coming-of-age story set in 1950s Maine. It follows two sisters, Cinthy and Ezra, the daughters of one of the town’s few Black families, as they balance on the edge between girlhood and womanhood. The world that begrudgingly accepted them as children becomes outright hostile as they become Black women, and the alliances they thought they understood—with a white friend, Ruby; with their parents and neighbors—begin to shift in ways they don’t fully comprehend. Meanwhile, in the wider world, the civil rights movement continues to gain force.

More From Harper’s BAZAAR

“I probably was working on Promise for many years before it really became this physical book. It really germinated when my mother passed away in 2014,” Griffiths says. “By the time my mom was making her transition, this young girl’s voice, [Cinthy],was really alive in me.”

Promise is preceded by a long career as both a poet and visual artist. Griffiths has written four books of poetry, the most recent of which, Seeing the Body, won the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award in poetry and the Paterson Poetry Prize in 2021. “I always wrote fiction at the same time that I wrote poetry,” Griffiths says. What becomes a poem versus a piece of prose “depends on what lands and starts to gather its own nucleus and its own heartbeat. As I’ve gotten older and more and more comfortable, I’m less explicit of the box. I like the oxygen and energy around being open. I am the truth of many things simultaneously happening.”

Griffiths grew up in Washington, D.C. and Wilmington, Delaware. The daughter of a lawyer and a former police officer, she was the oldest of four children and describes herself as “very sensitive, dreamy, a bit bookish and feral” as a child. Like many artists, she became fascinated with her family and community around her. “Since I was a child, I have been captivated by Black women,” she says. “How we raise ourselves, how we raise each other, the space of mothering and daughters and just the whole village and lineage—the whole world of it is just astonishing. It’s a constellation that guides everything in me.”

It’s a thread that runs through both her writing and her work as a photographer. Her photographs uses stark shadows and whites to produce haunting representations of Black women. Griffiths plays with the question of interiority. “It’s a continuation of what [W.E.B.] Du Bois calls ‘double consciousness in the veil,’” she explains, referencing the sociologist and writer’s famous metaphor for Black consciousness in an anti-Black world. “It’s also gender and femininity and sexuality … all of those things that don’t really align and sometimes do cross over into the exterior world. I am very committed to having deeper self-knowledge. That interiority, the inner narratives of Black girls and Black women is the spinal cord, the heart, the rib cage of my work.

“I’m completely consumed with the dream narratives of Black women in my photographs, how to make that visible,” she says. “[T]hat black women have dreams in our lives that are valuable for their own sake and they’re not for anybody [else]… they are profound spaces of intuition and imagination and invention and liberation.”

But, Griffiths warns, the Black tradition that can be so grounding “can also be a kind of corset or vise or grip.” A key inspiration for Promise, she says, is the famous scene in Zora Neale Hurston’s 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God “where the granny is talking about Black women being the mules of the world” in contrast to “the delicacy of the pear blossom and of sensuality and texture.”

“We’ve seen for hundreds of years this [narrative of a Black woman’s] warrior struggle—carrying everybody’s trauma, everybody’s baggage,” Griffiths says. “And if we do that, then we can be authentic Black women, then we have a name and we have a role and we should be respected. But we know that doesn’t happen.”

Instead, Griffiths says, “I want to deliberately assert that right to the dream world, to delicacy, to sexuality, to boldness—not because it’s by force, but because I’m living my best life. I’m bold, I’m here. I’m amazing, my thoughts, my everything, my oxygen.”

The sisters in Promise must contend with a harrowing legacy of racial and familial violence, but reading the book, I was struck by the stark beauty in the New England landscape that surrounds them, that they are alert to even as they begin to understand the world’s dangers. “It almost feels frightening,” Griffiths says, “to choose delicacy, to choose softness, without feeling you’re betraying some of the warriors and heroes and women who have gone before you and whose shoulders you stand on by saying, ‘I don’t even want to do that discourse.’”

Refusing that narrative is an act of survival as much as it is a political discourse. Griffiths speaks of the Black women artists and writers she has known who have become chronically ill or developed health problems because of the trauma they have lived through. In her own life, she has had to navigate the grief of not only losing her mother, but also a close friend in the past years. In 2021, she married novelist Salman Rushdie, and had to contend with his attempted murder last summer at a reading in Chautauqua, New York. Melancholy and wistfulness are parts of her work, but she makes a distinction between the pain she has lived through and the emotions she explores in her artistic practice.

“In writing and also the art world, there is this belief that you have to go through mental anguish around your work to make it better, that a harsh life is somehow true to an artist. For me, the whole language and psychology of ‘You are more of a person or you have more substance because you have been traumatized or oppressed, and that is what makes you valuable’ … I don’t need that, personally, in my own life. Let me be resilient,” she says, “but not at the hands of brutality.”