On Aug. 18, 1920, U.S. Congress ratified the 19th Amendment, granting women the right to vote for the first time. In Boston, more than 50,000 women registered to vote in that’s year’s presidential election.

Evidence of that historic moment 103 years ago have long been available in the form of 160 volumes of voter registration records in the city’s archives. Now, a team of archivists and transcribers are digitizing them and making the records searchable as part of the Mary Eliza Project: Boston Women Voters in 1920.

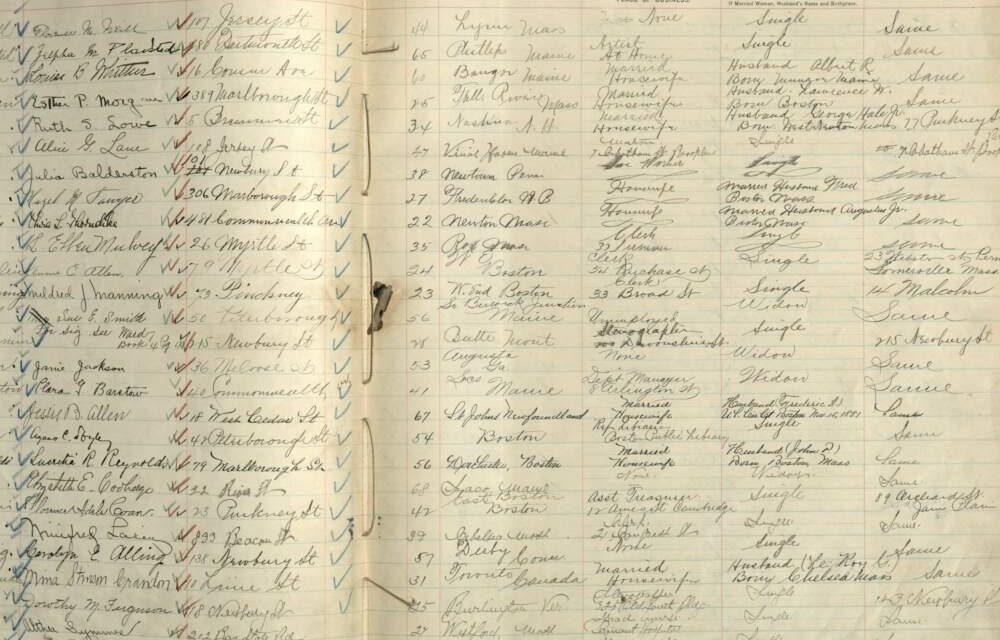

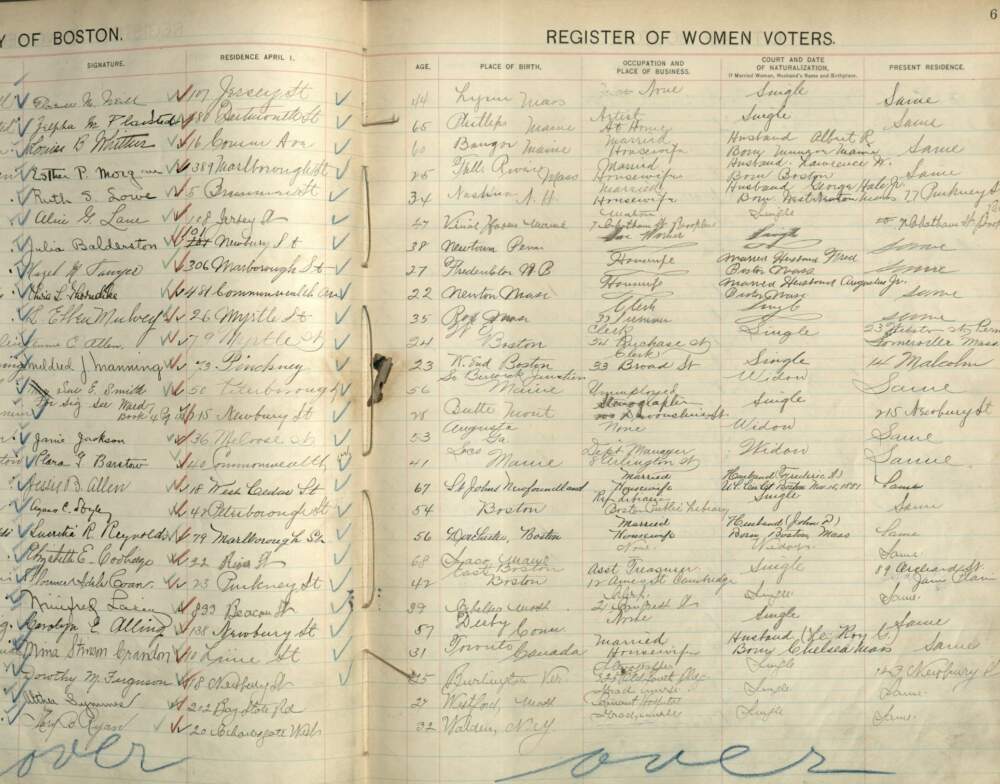

“They are oversized, with beautiful handwriting, very clear fields. It looks like a spreadsheet when you look at them, but they’re also very hard to use despite their excellent condition,” said Marta Crilly, an archivist involved in the project.

She added that besides the handwriting being hard to read at times, the record are not indexed or organized alphabetically. Rather, names of women were written down in the order they appeared in line.

Crilly, along with Erin Wiebe, a graduate of Simmons University, and Laura Prieto, scholar in residence at Suffolk University, spoke to Radio Boston about the project and what they’ve discovered about the lives of women in Boston at the time.

Setting the scene

Registration occurred over the 10-week period between Aug. 2 and Oct. 13. Beyond showing the sheer number of women registering, the record also offers a glimpse into the frenetic scene at polling places.

“We can see the excitement … in the handwriting in the registers. On Oct. 13, the last day women could register to vote, we can see the clerk’s handwriting sometimes getting messier and messier,” said Crilly. “And you can kind of sense the crowds of women that are lined up registering to vote on the last day.”

In response to the high turnout of registrants, the city election department had to hire more staff members. It set up special booths in individual wards where people could register until 9 p.m., which was ideal for working women who couldn’t get to City Hall before closing.

What the records reveal

The registration record included details like citizenship, occupation and place of birth.

Birthplace

Wiebe notes that the “place of birth” field in particular proves that scores of working class, immigrant and women of color lived in Boston. It also shows that many Jewish women were immigrating from parts of what is now known as Eastern Europe but would have been logged as Russia.

Occupation

Though women held a variety of jobs in places like factories and offices, the most common occupation they listed in their voter registration was housewife, Prieto said.

Housewife may have been how they identified for government record keeping purposes, but additional digging by the research team unearthed more interesting stories about the individual women.

Anna Coleman Ladd was one of these women who listed her occupation as “housewife.” But she was also an accomplished sculptor and portrait artist who won a Legion of Honor for the more than 200 sculptures she made of soldiers injured in World War I who had severe facial deformities.

She was a sculptor and portraitist by training. She had gone to the Boston Museum School and she had a thriving career when World War I broke out.

“Some of those men didn’t even really want to appear in public or reconnect with their families because of their, you know, internalized feelings about their appearance and how it had changed,” Prieto said. “So in her studio, she would invite in these individual soldiers and make casts of their faces.”

Other times, women were forthright in their descriptions. Eva Ledgate listed herself as an ordained congregational minister. Though many women were registered as church worker or missionary, it was rare to be a minister, especially one who preached before all-male congregations.

“What I really appreciate about her story is how unexpected it is to a lot of us in 21st century U.S. And it shows how women in the past don’t always fit neatly into the roles that we imagine for them,” Crilly said.

Addresses

“Women are listing their address where they’re currently residing and they’re listing their occupation, Wiebe said. “So from these two things, we can find where women were forming communities across the city.

Cross-checking information in that way allowed researched to create a deeper understanding of the community women had built for themselves across the city, according to Wiebe. For example, up to 800 working women and students lived in South End’s Franklin Square House at the time.

“What’s really exciting is that we found over 100 resident names in the register book signing up to vote,” Wiebe said. “So that’s a really big number from one address.”

About the project’s namesake

Mary Eliza Mahoney, for whom the project is named, is recorded as the first formally trained Black nurse in the U.S. and is recognized as one of the first women to register to vote in Boston. She was 76 years old at the time.

“One of our motivations … is that we wanted to really capture the wide range of women who are claiming the right to vote,” Prieto said. The popular narrative around the 19th Amendment centers on women who had “the leisure, the time to be able to volunteer, certainly to be leaders in the national suffrage movement, were quite elite and almost entirely white.”

“But we were wondering when it came to the moment of actually claiming the right to vote, were Black women in Boston, for example, claiming the right to vote?” she said. “Isn’t that a better way to define what a suffragist was?”

About half of all 50,000 voter registration records have been digitized so far. The team estimates all records will be available in their database by spring 2024.