Time for a different sort of commercial break.

Any subscriber to the ad-supported version of Hulu is bound to encounter the usual assortment of TV commercials that regularly interrupt a binge-watch of anything from “Only Murders in the Building” to “NYPD Blue.” Sometimes, a different sort of pitch pops up.

This one only surfaces when users stop the action on their own to take a call, grab a snack or hit the bathroom. “Need a break?” asks an on-screen graphic from Procter & Gamble’s Charmin during a halt in one recent stream. The toilet paper’s colorful bear mascot makes an appearance. “Enjoy the go.” There are other ads with similar themes. One on-screen entreaty for Hershey’s Kit Kat shows one of the candy bars in pieces and says, “Have a break.” One from Berskhire Hathaway’s Geico tells viewers to “Hold the phone.”

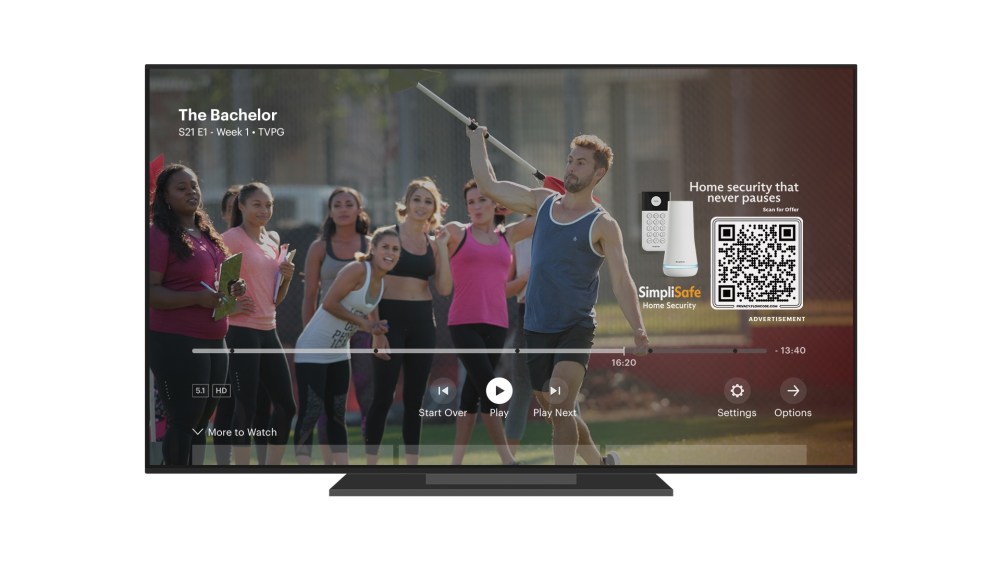

So-called “pause ads” — they only turn up a few seconds after a viewer has decided to halt the programming, and not every time one does — are seeing new movement in the streaming world, with the format appearing more frequently on Hulu since July, according to Josh Mattison, senior vice president of revenue management and operations for Disney Advertising. Pause ads are also in motion in venues such as NBCUniversal’s Peacock and Warner Bros. Discovery’s Max.

As more media companies seek to goose subscriber rates by offering cheaper ad-supported versions of their streaming services, this type of commercial may become more handy. One of the main attractions of streaming, after all, is that it boasts fewer traditional commercials than its linear TV counterpart. The industry hopes that a pause ad — other “out of pod” commercial experiences are also in development — can appear on screen without upsetting a subscriber who gets viscerally roiled by the prospect of a glut of typical TV spots.

“There are hundreds of millions of pauses, done for all the reasons we hit pause at any moment,” says Mattison. “We look at that as an opportunity for advertisers.”

Others have also found ways to work ads into the moments when streaming fans come to a stopping point. NBCUniversal’s Peacock launched with pause ads, says Peter Blacker, executive vice president of streaming and data products for NBCUniversal’s ad-sales division, while Warner Bros. Discovery’s Max introduced them in 2022, says Ryan Gould, head of digital ad sales and client partnerships at the company.

No one has been holding back on the new format. Hulu has experimented with pauses since at least 2018, and an early version of the idea surfaced last decade when Coca-Cola and Universal Pictures tested concepts with ReplayTV, an early backer of digital video recording technology. Coke, which once used the slogan “the pause that refreshes” to great effect, and Charmin, the Procter & Gamble toilet tissue that can offer succor during many breaks in TV viewing, tested the format with Hulu in 2019.

The stakes are high. Despite subscribers’ disdain for watching commercials, more streamers are adopting advertising, cognizant that they need the revenue it brings with it.

Even one-time staunch resisters like Netflix and Amazon are getting involved. Netflix unveiled an ad-supported tier in late 2022, and Amazon is expected to make advertising the default model for its Prime Video service unless subscribers cough up a few more dollars per year. Roku weaves ads for McDonald’s and others into its Roku City backdrop that serves as the hub screen of its service.

All of that suggests that ads are headed to streaming with increasing velocity. A “pause ad” might help the streamers add to their commercial offerings without annoying subscribers (at least, not too much). Pause ads and other ideas like them don’t extend the interruption of a typical commercial break. Instead, they only try to take advantage of a rest initially called for by the viewers themselves.

Getting the balance right between ads and content is critical. “Having a bad experience or having a lot of ad clutter erodes the impact of ads and is really bad for users,” says Kara Manatt, executive vice president of intelligence solutions at Magna, a media-research unit of advertising giant Interpublic Group. “We found in research that they may actually change their behavior because of this. They may actually cancel their streaming service.”

Such sentiment can weigh heavily on those charged with developing increasingly popular ad-supported streaming models. Max allows just one pause ad “per user per session,” says Gould, the Warner Bros. Discovery executive. “It’s a very limited experience” designed to lessen the feeling that a viewer’s binge is stuffed with commercials. Peacock offers advertisers a “power break” in which pause ads are designed specifically to appeal to specific smaller groups of audience, says Blacker. “It allows us a chance to customize the copy, the color, the language” based on data about Peacock users. “It’s one of our first full-scale uses of leveraging data to create unique ads for different groups of people.”

Media companies are trying to make the pause ads more useful than typical video commercials. A 320-second TV ad is generally used to generate awareness of a product, so that customers will remember it when the time comes to shop. But pause ads are now appearing with QR codes that let viewers click to find out more information about what’s for sale, or even go shopping.

While the people who stream their TV favorites may not want to watch that many ads, advertisers are eager to inject them into the experience. As more people leave traditional primetime TV, big advertisers like Apple, General Motors and Pfizer want to follow. “There are only so many minutes in commercial time on streaming when compared to TV,” says Julie Berger, chief media officer of the ad agency Giant Spoon. “The buy side wants the inventory. There is a lot of sell out, and it becomes hard to get in front of premium content.” The pause ads “feel non-intrusive, and in some cases there’s even a value exchange back to the end consumer.”

Pause ads could get a shake up as technology develops. Imagine if a full-motion video ad were to start playing a few seconds after someone decided to take a break in their streaming action, or if streamers decided to cede the full screen to an advertiser durign pause time. “All that is in the realm of possiblity and, quite frankly, capable today,” says Berger. But she thinks more work needs to be done. “What about an expeirence you could click to if you wanted to learn more?” she asks. Max executives would be wary of making a subscriber feel like they faced a new delay in getting back to their chosen entertainment, says Gould. “I think there are definitely interactive opportunites where you can carry on video storytelling, but the creative execution wil have to be clear to the consumer, because they’d be toggling between two video experiences.”

In some cases, pause ads have already forced streamers to stop and think. Max has done work to ensure that the commercials look a little different when they appear during kids’ programming, so that younger viewers know they are seeing an ad, not more content.

The company also won’t use pause ads when viewers are watching something for mature audiences, out of concern a commercial message might pop up alongside a scene that features violence or nudity. Some of the elements in the Max dating program “Naked Attraction,” in which full-frontal nudity is used to determine whether a couple might be suitable, can stop viewers in their tracks. Pause ads won’t be one of them.