How Do We Fix the Scandal That Is American Health Care?

This is the third in the series “How America Heals”

in which Nicholas Kristof is examining the interwoven crises devastating parts of America and exploring paths to recovery.

It’s not just that life expectancy in Mississippi (71.9) now appears to be a hair shorter than in Bangladesh (72.4). Nor that an infant is some 70 percent more likely to die in the United States than in other wealthy countries.

Nor even that for the first time in probably a century, the likelihood that an American child will live to the age of 20 has dropped.

All that is tragic and infuriating, but to me the most heart-rending symbol of America’s failure in health care is the avoidable amputations that result from poorly managed diabetes.

A medical setting cannot hide the violence of a saw cutting through a leg or muffle the grating noise it makes as it hacks through the tibia or disguise the distinctive charred odor of cauterized blood vessels. That noise of a saw on bone is a rebuke to an American health care system that, as Walter Cronkite reportedly observed, is neither healthy, caring nor a system.

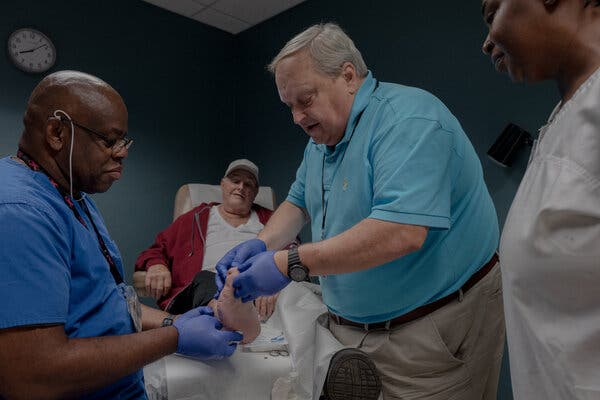

Dr. Raymond Girnys, a surgeon who has amputated countless limbs here in the Mississippi Delta, one of the poorest and least healthy parts of America, told me that he has nightmares of “being chased by amputated legs and toes.”

“It starts from the bottom up,” Dr. Girnys said, explaining how patients arrive with diabetic wounds on the foot that refuse to heal in part because of diminished circulation when blood sugar is not meticulously managed in a person with diabetes. Dr. Girnys initially tries to clean and treat the lesions, but they grow deeper, until he has to remove a toe.

When more wounds develop, he takes off the foot in the hope of saving the rest of the leg. New wounds can force him to amputate the leg below the knee and perhaps, finally, above the knee. After that, Dr. Girnys said, the patient is likely to die within five years.

A toe, foot or leg is cut off by a doctor about 150,000 times a year in America, making the United States a world leader of these amputations.

I’ll be blunt: America’s dismal health care outcomes are a disgrace. They shame us. Partly because of diabetes and other preventable conditions, Americans suffer unnecessarily and often die young. It is unconscionable that newborns in India, Rwanda and Venezuela have a longer life expectancy than Native Americans newborns (65) in the United States. And Native American males have a life expectancy of just 61.5 years — shorter than the overall life expectancy in Haiti.

But there are fixes, and three in particular would make a huge difference: expanding access to medical care; more aggressively addressing behaviors like smoking, overeating and drug abuse; and making larger society-wide steps to boost education and reduce child poverty. One reason to believe that we can do better on health care outcomes is that much of the rest of the world already does.

This is the third essay in my series about how we can better help the millions of Americans left behind. We in journalism mostly cover problems: We typically write about planes that crash, not planes that land. But this series aims to offer solutions to challenges our nation faces.

A Superpower Where Many Citizens Die Young

A starting point is to avoid the myopia of Russia when it experienced a drop in life expectancy beginning in the 1980s and a rise in “deaths of despair.” Leaders took comfort in Russia’s status as a military superpower and a standout in the sciences and performing arts; they blamed individuals’ lack of personal responsibility for the deaths. They didn’t understand that when so many people are sick and struggling, the ailment is deeper than individual weakness.

Americans sometimes blithely boast of the best medical care in the world, and there is some truth to that. I have a friend who is alive today because of the success of immunotherapy to fight stage IV cancer.

Our health technology and cutting-edge medicine is superb. Yet whatever the quantity and quality of our bone saws, the tragedy is that they are so often needed.

America’s health crisis is most evident among low-education and low-income Americans, notably people of color and particularly men.

“The poorest men in the U.S. have life expectancies comparable to men in Sudan and Pakistan; the richest men in the U.S. live longer than the average man in any country,” researchers with the Opportunity Insights team at Harvard concluded. But while the gaps we focus on have to do with mortality, there are also enormous gaps in quality of life.

“It’s very rare that I’ve got somebody in that has just one health problem, or in for a wellness visit,” said Yvonne Tanner, a nurse practitioner in the Mississippi Delta town of Itta Bena, with a population that is largely poor and Black. “Everybody that I see is already very, very sick.” Most have multiple diagnoses, she said, of hypertension, diabetes, arthritis and more.

Tanner choked up and her eyes welled as she told me of a patient she had just seen, a 47-year-old woman with poorly managed diabetes whose legs were severely swollen. The woman didn’t know why; Tanner did. It was end-stage kidney failure.

That patient, who has teenage children, has a job, but it’s not clear how she can keep it while getting three sessions of dialysis each week.

Type II diabetes, the kind that is linked to diet and inactivity, used to be called adult-onset diabetes but now affects children as well — and it encapsulates American ill health. It reflects the brilliance of soda companies and fast-food companies at marketing their products — in ways that are good for corporate profits but disastrous for American health. Type II diabetes often strikes the poor and marginalized who live chaotic lives without insurance, seek cheap calories in food deserts and struggle to manage budgets and insulin levels. The upshot is often dialysis, amputations and disability.

Statisticians have tried to calculate what they call “healthy life expectancy” in a population — the number of years an average person in a country can live a normal life, before amputations, dialysis, blindness or other setbacks. In the United States, that is just 66.1 years, shorter than in Turkey, Sri Lanka, Peru, Thailand and other countries that are much poorer. My dad was an Armenian refugee who fled Romania and was thrilled to settle in America; now Armenia and Romania both have longer healthy life expectancy than the United States.

One Step Forward: Expand Access to Care

Here’s a simple step to improve access to health care: Expand Medicaid.

Ten states, including Mississippi, still have not done so even though nearly all the funds would come from the federal government. Partly as a result, some hospitals are cutting back services in Mississippi and are at risk of closing.

A cartoon in Mississippi Today recently showed a patient asking a doctor, “How long do I have, doc?” The physician replies: “Longer than this hospital.”

Even much poorer countries manage to provide universal health care. I visited hospitals recently in the West African nation of Sierra Leone, which mostly provides free prenatal care without any complicated bureaucracy, so 98 percent of women get some prenatal care — which appears to be a hair higher than in Florida. Granted, Florida medicine is far more sophisticated than that in Sierra Leone, but that may not matter for those outside the health care system.

Dr. Kim Sanford, an ob-gyn in the Mississippi Delta, told me about a 74-year-old woman who came in recently to have an IUD removed. She had had it inserted after her daughter was born 46 years ago and hadn’t seen a gynecologist since.

Some 28 million Americans lack medical insurance. An even larger number of Americans — 77 million — lack dental coverage.

Cost is often the argument against expanding access to health care. But it’s hard to understand how just every other advanced country can afford universal care and the United States can’t. And consider that 94 percent of Americans with substance-use disorder do not get treatment, even though this pays for itself many times over. Our policy often seems driven less by cost considerations than by indifference, even cruelty.

Improving access to health care can also take other forms, such as improving outreach and increasing diversity in the ranks of health workers. Researchers have found, for example, that Black patients have better outcomes with Black doctors.

Rethinking Health Behaviors

Those of us on the left have mostly been fighting to increase health care coverage, and that’s important. But outcomes are driven not just by access or socioeconomic status. Hispanics lack health insurance at high rates, yet have a longer life expectancy than white Americans and often a lower maternal mortality rate.

Part of the explanation for this “Hispanic paradox” may be strong families, community support systems and healthy behaviors. Raj Chetty, a Harvard economist, has found that behaviors — such as smoking, eating habits and exercise — affect life expectancy even more than access to health care.

One crucial fix, in short, is to influence health behaviors. This is difficult but not impossible. Just since 2005, the share of American adults who smoke has dropped by almost half. And America’s teenage birthrate has plummeted by an astonishing 77 percent since 1991, partly because of comprehensive sex education and increased access to long-acting contraceptives.

One step that might reduce consumption of sugary snacks is a soda tax, modeled on the cigarette tax. Such taxes are regressive but seem effective at reducing consumption of harmful products.

More fundamentally, though, self-harming behaviors arise from a context. The genesis for this series was a crisis in behavioral health in my hometown in rural Oregon, where more than one-quarter of the children on my old No. 6 school bus are now dead from drugs, alcohol and suicide. Looking back, the central problem was the same as in many working-class communities across the country: the loss of good union jobs followed by despair and loneliness — and the arrival of meth and opioids.

It was poverty, but a poverty of purpose as well as of the wallet. It was a hopelessness that sabotaged marriages and sapped self-esteem and self-care. In talking to doctors and nurses over the years, I’ve been struck by how often they mentioned that men are reluctant to get preventive care or treatment. They say that when men do come in, it’s often because they’re nudged by their wives — but as the institution of marriage has crumbled in working-class America, there often aren’t wives to save their husbands’ lives.

Researchers tried to calculate how many people poverty kills each year in the United States, and their estimate was 183,000 — many times the number of homicides annually.

Dr. Thomas Dobbs, the dean of the school of population health at the University of Mississippi, wrestles daily with health consequences of inequality, including syphilis that is now spreading rapidly. I asked Dr. Dobbs what he would most like to do to improve health outcomes, and I assumed he would name some medical interventions.

“Desegregate schools and fix criminal justice,” he said. “That’s what I would do.”

The point is that America’s health dysfunction is rooted in a broader national dysfunction, including deep intergenerational poverty and despair. The medical system can efficiently amputate a foot, but an improvement in self-care of diabetes sometimes requires an injection of hope and improvements in education, job training, earnings and opportunity.

This is important because in America our problem is not just that people die in their 70s rather than their 80s. Dr. Steven H. Woolf of the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine has found that because of guns, suicides and accidental deaths, child mortality in the United States is rising rather than falling — in a way that he doesn’t believe has any precedent in the past 100 years.

As a result, notes John Burn-Murdoch of The Financial Times, in any class of 25 American kindergartners, one child on average will die by middle age.

Dr. Yasmin Cheema, a pediatrician in the town of Clarksdale in the Delta, told me of the obesity and diabetes she sees even in children. A 10-year-old boy recently fainted in her waiting room; it turned out that he was in shock with undiagnosed diabetes. Dr. Cheema called 911.

After telling me the story, Dr. Cheema stepped into the next room to do a physical on a 14-year-old boy. He weighed 295 pounds.

A Model in the Mississippi Delta

One model effort to reach young people and address behaviors in the Mississippi Delta is the Delta Health Alliance. It has helped build a wellness center in the town of Leland, with a gym, yoga classes and an on-site nutritionist who teaches how to cook healthy meals.

The Delta Health Alliance tries more broadly to address the “social determinants of health” that sometimes lead to obesity, smoking and poor health outcomes. This means supporting education beginning with pre-K, promoting mentoring, organizing job training and much more.

“We realized we could help a lot of 50- or 60-year-old diabetics, but that’s not fixing the problem, the generational poverty problem that starts when kids are born,” said Karen Matthews, president of the Delta Health Alliance.

The alliance tracks metrics closely, and its approach seems to be reducing poverty and improving health outcomes. It’s as essential an investment in health as CT scanners.

More broadly, we know how to cut child poverty, because we’ve done it: The United States cut it by almost half in 2021, largely with the refundable child tax credit. But Congress allowed the program to lapse, and child poverty is rising again.

Some may scoff that short life spans are a result of personal irresponsibility, such as eating too many sugary snacks, exercising too little or abusing alcohol. It’s true that personal choices shape our health, but so do our collective choices about expanding Medicaid, extending the child tax credit, providing adequate drug treatment and educating people about health choices. If we believe in personal responsibility for others, we should accept collective responsibility for ourselves.

It would have been unimaginable even a decade ago that Bangladesh could overtake an American state in life expectancy. That is a reflection of our choices, personal and collective, and we can do better.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

September Dawn Bottoms is an award-winning documentary photographer based in Oklahoma. Her work focuses on mental illness, family, poverty, and the intersection of the three.