The maternal death rate in Minnesota grew steeply between 1999 and 2019, according to new data published this week in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

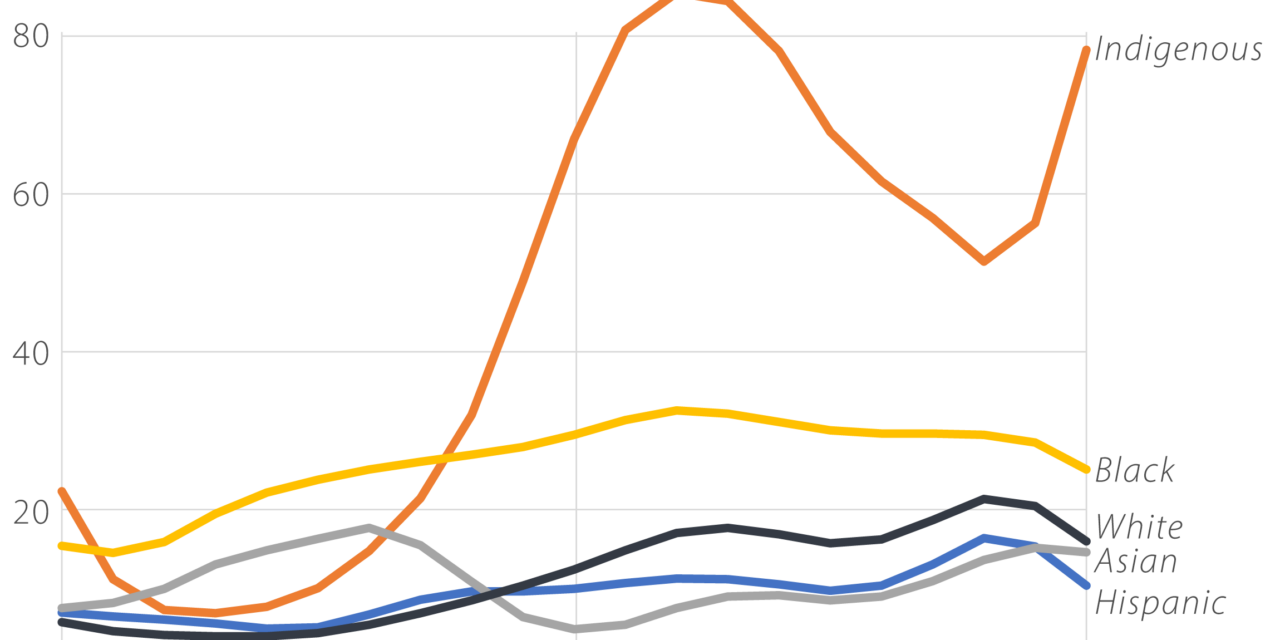

The risk of death for Black, Asian and Hispanic mothers has roughly doubled since the turn of the millennium, according to the study. The mortality rate for white moms has tripled, while Indigenous women in Minnesota are now about 10 times as likely to die during or after pregnancy as they were 20 years ago.

Some of the rise in maternal mortality nationwide is a factor of women delaying childbirth until later in life, when complications are more likely, and of an increase in rates of chronic health conditions like obesity and hypertension. The Indigenous community in Minnesota experiences particularly high rates of poverty and poor health, which are reflected in the community’s extremely high maternal death rates.

As bad as those numbers are, Minnesota’s overall maternal mortality rate of 18 deaths for every 100,000 live births is the third lowest in the nation. Mothers in southern states like Alabama, Mississippi and Georgia are about three times more likely to die during childbirth than women in Minnesota.

“In the U.S., maternal deaths are often caused by vascular diseases like severe high blood pressure or blood clots,” said Greg Roth of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, one of the authors of the report. “So maternal deaths share many of the same drivers as heart attacks, strokes, and heart failure.”

Mothers in Minnesota tend to receive better health care than their counterparts in many other states, according to a report from the March of Dimes. The state has also adopted a number of policies that support maternal health, including expanded Medicaid coverage for pregnant and postpartum women, policies to support midwives, and good data collection practices to help understand the drivers of maternal and infant death.

The JAMA study tallied maternal deaths that happened during pregnancy or within one year of birth. Deaths due to unintentional injuries, drug overdose, homicide or suicide were excluded from the analysis. The United States is a maternal mortality outlier among the world’s developed nations, with rates roughly three times higher than those seen in other wealthy countries.

One defining feature of American maternal death rates is wide disparities between different racial groups. In Minnesota, maternal mortality rates in 2019 ranged from 10 deaths per 100,000 live births for Hispanic mothers to nearly 80 deaths for Indigenous women.

Separate data released last year by the state of Minnesota found that “Black Minnesotans represent 13% of the birthing population but made up 23% of pregnancy-associated deaths, and American Indian Minnesotans represent 2% of the birthing population, but 8% of pregnancy-associated deaths.” Infections and cardiovascular issues were the main drivers of pregnancy-related deaths in Minnesota, the report found.

“In one of the healthiest states in the country, Black and Indigenous moms are dying at a rate that far outstrips their share of the population,” Dr. Rachel Hardeman, director of the Center for Antiracism Research for Health Equity at the University of Minnesota, said at the time. “It is a reflection of the historical legacy of structural racism that has shaped current inequities in maternal mortality. These deaths are 100% preventable.”

The recent death during labor of star track athlete Tori Bowie, a Black woman in seemingly perfect health, underscored the grim realities facing many Black women attempting to navigate the country’s patchwork maternal medicine system. It’s “critical for physicians and other health care workers to recognize and check internal biases and cultural stereotypes that contribute to patient oppression and higher mortality rates in women of color,” Omare Jimmerson, executive director of the Tulsa Birth Equity Initiative, wrote in a recent op-ed.

Additional factors are also contributing to rising maternal mortality across the board. Women are having babies at older ages than in previous decades, with the median maternal age rising from 27 to 30 between 1990 and 2019. The risk of health complications during pregnancy rises dramatically with age.

America’s largely privatized medical insurance system is also partly to blame, according to experts who study differences between the United States and other countries, as is the lack of a guarantee for paid maternity and paternity leave. In 2012, for instance, data showed that one quarter of new working mothers were back at work within two weeks of having a baby.

All of those factors create similar health challenges for America’s newborns, who also die of preventable causes at a much higher rate than their peers overseas. As with maternal death, Minnesota’s rate of infant mortality is lower than that of most other states.

One important caveat to these numbers is that they only go through 2019. Provisional data shows that maternal deaths increased sharply again during the pandemic, with racial disparities persisting. And many Republican-led states have passed strict bans on abortion in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, which may ratchet maternal death rates even higher in the coming years.