A crowd of renters that was mostly women and mothers, peppered with Black and Latino men, packed the North Las Vegas Justice Court for its two afternoon eviction court sessions last Tuesday. A considerable portion of testimonies required a Spanish language interpreter and tenants left the courtroom confused, frustrated and in tears after being told to leave their homes by today in order to avoid forced physical removal.

With wages that have stagnated for years and a June 5 expiration of a coronavirus safety net that required landlords to keep tenants housed for at least 60 days if residents applied for rental assistance, Southern Nevadans are being flushed from their homes, with some moving out of the region altogether.

“It really is one of those things that it just sucks for everybody involved,” said Justice Belinda T. Harris during an interview with The Nevada Independent on Monday night.

She has invited elected officials into her courtroom to observe eviction proceedings, noting that the money owed by some residents was striking.

Tenants who have stood before her owed anywhere from $1,300 (one to two months of rent) to upward of $15,000. In some instances, residents faced multiple eviction notices.

“It’s not something that is black and white or gray,” said Harris, who became the first Black judge in North Las Vegas in 2021, about what’s happening in her courtroom. “It’s very, very colorful, from all angles.”

About 40 people pleaded their cases to Harris on July 18. The majority of tenants represented themselves, and were being removed from their homes because of lack of payment. Most had to vacate within about seven days. Some were employed, some were jobless and some were on fixed incomes.

The court cases come as corporate landlords have rapidly changed the housing market in Nevada, and across the country, with skyrocketing rents following the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Out-of-state corporate investors have driven the price of rent up 25 percent to 40 percent since 2019 causing some residents to seek rent control policies (such as in North Las Vegas in 2022) in order to prevent price gouging and inspire other municipalities to do likewise. Those measures fell short when officials rejected a Culinary Union-backed ballot initiative that would have capped rent increases at 5 percent year over year.

A report from Princeton University’s Eviction Lab indicates that June saw a 170 percent increase in eviction filings in the Las Vegas Valley, compared to the number of filings during the same month before the pandemic. The report, which extrapolates data from courts in Southern Nevada, found that nearly 5,000 filings were made last month. In total, the report found that since May 2020, 123,422 eviction filings were made with nearly 60,000 evictions filed this past year — a 160 percent increase since before the pandemic.

Nevada’s summary eviction process requires a tenant to make the first legal filing against a landlord if they receive a notice to vacate, or they must leave within seven days to avoid physical removal by a constable, being locked out of the property or an actual eviction, which is detrimental to their rental histories. After an eviction takes place, Experian, a business services company that tracks credit scores, warns customers that the eviction is kept on a tenant’s rental history for seven years, making it difficult for them to find a place to rent in the future.

“There’s no other process in civil practice where the defendant has to answer first,” said Assemblywoman Shondra Summers-Armstrong (D-Las Vegas) at the courthouse – the sole legislator to accept Harris’ offer to observe proceedings, though the judge said she is expecting more lawmakers to make their way into court in the coming weeks.

Mauro Rojas, 35, was among those in eviction court on Tuesday. Rojas, who has two rent-to-own mobile home agreements at Greenspot Mobile Home Village on Las Vegas Boulevard near Carey Avenue, gave an eviction notice to his subleaser, Muliaiga Sapini, 64, who he was illegally renting to, and ended up in court himself, facing an eviction notice from his landlord.

Sapini said she found out about the eviction notice on Monday and claimed that because she paid her rent, she should be able to stay in her home — but Rojas said she owes him about $5,000 in unpaid rent from a year prior.

“If you have proof of that, you can bring it to my office,” Kevin Turcios, 33, the property manager at Greenspot, told Sapini in the hallway inside the courthouse. “I want to keep people in their homes.”

Jonathan Norman, the advocacy outreach policy director at Nevada Coalition of Legal Services, said lawmakers have tried to change the summary eviction process since at least the 1980s, with the latest attempt vetoed by Republican Gov. Joe Lombardo. In 2021, Democrats kept their hands off the process as well, and walked back a proposed policy that would have abolished summary evictions in order to avoid upending the system. Instead the measure was whittled into a study that ultimately also didn’t pass.

“I think that there’s probably an uptick [in evictions] right now, because when certain laws are in place and certain protections, then people behave a certain way,” Harris said. “And that’s landlord and tenant, tenant and landlord. So, I think there may be an uptick but I think that what’s kind of got people shocked, is the amounts that are owed.”

Chelsea Powell, 29, who is almost full-term in a pregnancy and also has a 6-year old, attended eviction court for what she thought was missing rent from March but was surprised to learn she had multiple fillings from her landlord, who is no longer accepting rental assistance payments from the Clark County CARES Housing Assistance Program (CHAP). She owed nearly $4,000 for two months rent.

Powell said she had been in contact with her landlord who she said never told her he was no longer accepting CHAP payments and that she would be applying again. In a follow-up interview, she said her application was approved the day after her court appearance.

“He just got a check for $15,000 at the end of May from the CHAP program,” Powell said. “So it kind of [caught me by surprise].”

With just seven days to leave their home, she and her husband said they plan to move in with a friend until she goes into labor, which could be “any day now,” and then move back to Atlanta, Georgia, where she is from, into one of the homes her grandmother owns.

She said she fell on hard times after being pregnant with twins and then losing one, which sent her to the hospital, causing her to miss numerous days of work as a leasing agent. Her employer fired her for the absence despite her condition.

“I literally just asked for a couple of weeks off,” Powell said. “And then they said due to my attendance, they had to let me go. And I’ve been trying to find something else but it’s hard, especially now, because I’m big and pregnant.”

Powell, who has a bachelor’s degree in business administration, said that when she moved to Las Vegas in 2015 she paid less than $1,400 for a “big apartment with wooden floors and a two-car garage in Southern Highlands” and remained in that area until last year when she moved to North Las Vegas into The Alowyn apartments on Centennial Parkway with a $2,400 rental rate for less space.

“The pay is too little and the rent is too high,” Powell said. “Even with a degree you don’t get paid [well enough] out here.”

Though rents are not as high as they were last year at this time, the average cost to rent an apartment in Nevada is still above what is considered affordable — 30 percent or less of the average resident’s monthly income. The Nevada State Apartment Association reported the average cost to rent in Southern Nevada during the first quarter was $1,430 a month and $1,510 in Northern Nevada.

The median monthly income for Nevadans is almost $2,900, meaning a person living in Southern Nevada would need to make $1,390 more than the state median monthly income for the average rent to be considered affordable. A Northern Nevada resident would need to make about $1,630 more.

Additionally, after a short dip in the market, prices for apartments are once again beginning to climb with the average rent in Southern Nevada $10 more than it was during the last quarter and $20 more in Northern Nevada during the same time frame.

Housing policies recently vetoed

The rise in eviction court proceedings follows the end of a legislative session where numerous housing bills aiming to address the state’s eviction process failed to move forward. Gov. Joe Lombardo faced criticism from housing advocates and Legal Aid of Southern Nevada after he vetoed bills from Southern Nevada lawmakers that would have reformed Nevada’s unique summary eviction process, provided rent caps for seniors and extended eviction protections for people waiting on rental assistance.

Summers-Armstrong attempted to revise Nevada’s evictions practices by requiring a landlord rather than the tenant to make the first filing in an eviction case, an action Assemblywoman Selena Torres (D-Las Vegas) said during a meeting of the Assembly Judiciary Committee during the 2021 legislative session is “akin to requiring someone to sue themselves for an opportunity to mount a defense.”

However, Lombardo vetoed AB340. In his veto message, the governor said the bill would “impose additional and unnecessary delays and costs to those seeking to remove individuals who unlawfully remain on their property after termination of their lease” and “create an inhospitable environment for residential lessors.”

AB289, sponsored by Assemblywoman Sandra Jauregui (D-Las Vegas), would have provided rent caps for people older than age 62 or living off of income from Social Security, but it was also vetoed.

Sen. James Ohrenschall (D-Las Vegas) sponsored SB335, a measure that intended to prevent people with pending applications for rental assistance from being evicted for 60 days. This bill was an extension of AB486, which passed during the 2021 legislative session and expired June 5.

Assembly Speaker Steve Yeager (D-Las Vegas) wrote in a Twitter thread that the expiration of AB486’s eviction protections, summarily or otherwise, meant “a serious eviction crisis is looming in Las Vegas.” Yeager also highlighted several bills he thought would provide other tenant protections; however none gained Lombardo’s signature.

Lombardo said in his veto message that AB486 would create “onerous burdens in Nevada’s residential renting market.”

Because of these vetoes, progressive advocates — including Annette Magnus, executive director of Battle Born Progress — said Lombardo put the priorities of his largest campaign donor ahead of everyday Nevadans.

“Governor Lombardo is showing his hand time and time again by placing the desires of his ultra-wealthy donors over the needs of the people of Nevada,” Magnus wrote in a statement released through the Nevada Housing Justice Alliance shortly after these bills were vetoed in June.

Robert Bigelow, the owner of the Budget Suites of America hotel chain and outer space technology company Bigelow Aerospace and a vocal critic of the federal eviction moratorium that was in place during the COVID-19 lockdown, became one of Lombardo’s largest donors after contributing about $30 million to the governor-elect and affiliated groups during the election.

Lombardo’s office told The Nevada Independent in June the suggestion that the governor acted with the favor of large campaign donors in mind was “simply ludicrous.”

Tenant protections also haven’t fared well in past sessions, even when Democrat Steve Sisolak was governor and held a Democratic majority in both the Senate and Assembly. Though a majority of housing bills did not succeed that session, the Legislature did pass several that contributed to rental assistance programs and supportive housing — including AB396 that provided funding for rental assistance and AB 310 that contributed $32 million for the Supportive Housing Development Fund.

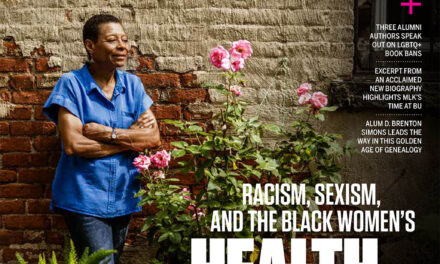

Women, children and ‘people of color’

Princeton’s Eviction Lab found that 3.6 million evictions filed in a given year is typical across the country. Other studies on evictions reveal a racialized system of displacement and its role in reproducing poverty mostly for women, children and the poor, with the highest number of instances involving Black women with children.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2022 population estimates, nearly 13 percent of North Las Vegas families, or close to 36,000 households, live in poverty. In Clark County, an estimated 15 percent — about 348,000 people — live in poverty or make $14,580 a year or less.

“We can’t make up for being short 80,000 affordable units,” Norman said. “I think we already have a homeless crisis, but I think it’s going to get way worse over the next six months especially.”

The National Equity Atlas reported that Black, Latino and Native American renters in Nevada were disproportionately housing insecure before the pandemic and that in 2019 no ZIP codes in Las Vegas were affordable to the average median income of Black households, which was $40,000.

As eviction protections implemented during the pandemic lift and costs for goods and services increase across the board because of inflation, advocates fear that housing insecurity and eviction rates will rise.

“Poverty is a huge driving factor [for evictions],” Norman said, adding that evictions are “devastating on neighborhoods.”

Other research findings

The National Library of Medicine found that housing eviction plays a significant role in poverty reproduction, which uproots roughly 1.6 million kids out of the 11 million children in low-income families, and 1 out 4 children living in deep poverty, which is about 1.3 million kids, at least once by age 15. However the data is unclear on how many people are displaced by evictions, because a Harvard study on “discrimination in evictions,” noted that most evictions begin with a printed notice about “involuntary removals” that almost always result in “voluntary removals,” meaning residents received a paper notice and left before the eviction process was completed.

In Evictions: Shedding Light on the Hidden Housing Problem, Kathryn Howell and Daniel William Immergluck explore the demographics and ramifications of evictions and gentrification in cities throughout the country in 2021. They found that eviction spikes in Las Vegas were associated with investor-owned homes and that in Madison, Wisconsin, evictions increased in areas “within 500 feet of development projects after they received permits.”

Howell and Immergluck’s study also showed that in Fulton County, Georgia, housing policy researchers found that “investor purchases were associated with a 33 percent increase in the odds of a subsequent eviction.” In the same region, an increase in investor-owned homes led to “significantly fewer Black residents, and more white residents in the associated census block group,” leading Howell and Immergluck to suggest that “ownership changes play a role in racialized gentrification.”

Black renters across the country expressed the least amount of housing security among respondents behind on rent in a 2021 report by National Equity Atlas.

A 2015 Harvard Law Review concluded that discrimination plays a large role in eviction filings, which includes data from 2003 and 2007, showing 60 percent to 70 percent of evictions in Philadelphia, Milwaukee and Chicago were women and that, in general, households with children were more likely to receive an eviction judgment. They also found “Hispanic tenants are significantly more likely to be evicted when they live in neighborhoods that have at least two-thirds white residents.”

Harris said she is seeing the raw end of the deal involving the eviction process in North Las Vegas, which is what led her to invite lawmakers to eviction court so they can “see how the process actually works” hoping that it would help them better serve constituents when making laws.

“I don’t think that anybody likes the unhoused population,” she said. “Some people don’t like to look at it because it doesn’t make them feel good. Some people don’t like to look at it, because it makes their heart hurt, literally.”

Surrounded by evictions

Lizette and Edward Gallegos are being removed from a home with a summary eviction issued by their children’s grandmother, who lives in California. The two have seven children ranging in age from 16 to 4.

“We lived in the Siegel Suites when we first moved out here,” said Lizette Gallegos, in a follow up interview with The Nevada Independent last week.

Gallegos said a seven-bedroom home was purchased by Edward’s mother for their family in 2019 to keep them stable after being subjected to evictions and displacement since 2016, when they moved to Las Vegas from California. The family of nine has struggled with housing ever since the move, at times cramming into one-bedroom weekly rentals, two-bedroom apartments or even couch surfing in the homes of friends.

“Nobody is going to rent to us with seven children,” she said Tuesday after hearing they must vacate the property in which they live by July 25.

They were asked to move out after paying rent in increments each month and using rental assistance through the CHAP program twice, once in 2020 and once in 2021. Edward Gallegos’ mother no longer wants to participate in the program, disliking how the payments are processed.

Lizette Gallegos said the change of tune started around May.

With plans in motion to go back home to visit family members in Kansas, Lizette Gallegos said they intend to stay there.

Harris said the diversionary program that expired last month was a new system for the state of Nevada and Clark County.

“And that is not necessarily to say that the laws are terrible or worse [now] … but it’s just that they went back to where they always were,” she said.