“By any means necessary” was no overstatement when it came to the life-or-death flight to freedom through Illinois’ Underground Railroad.

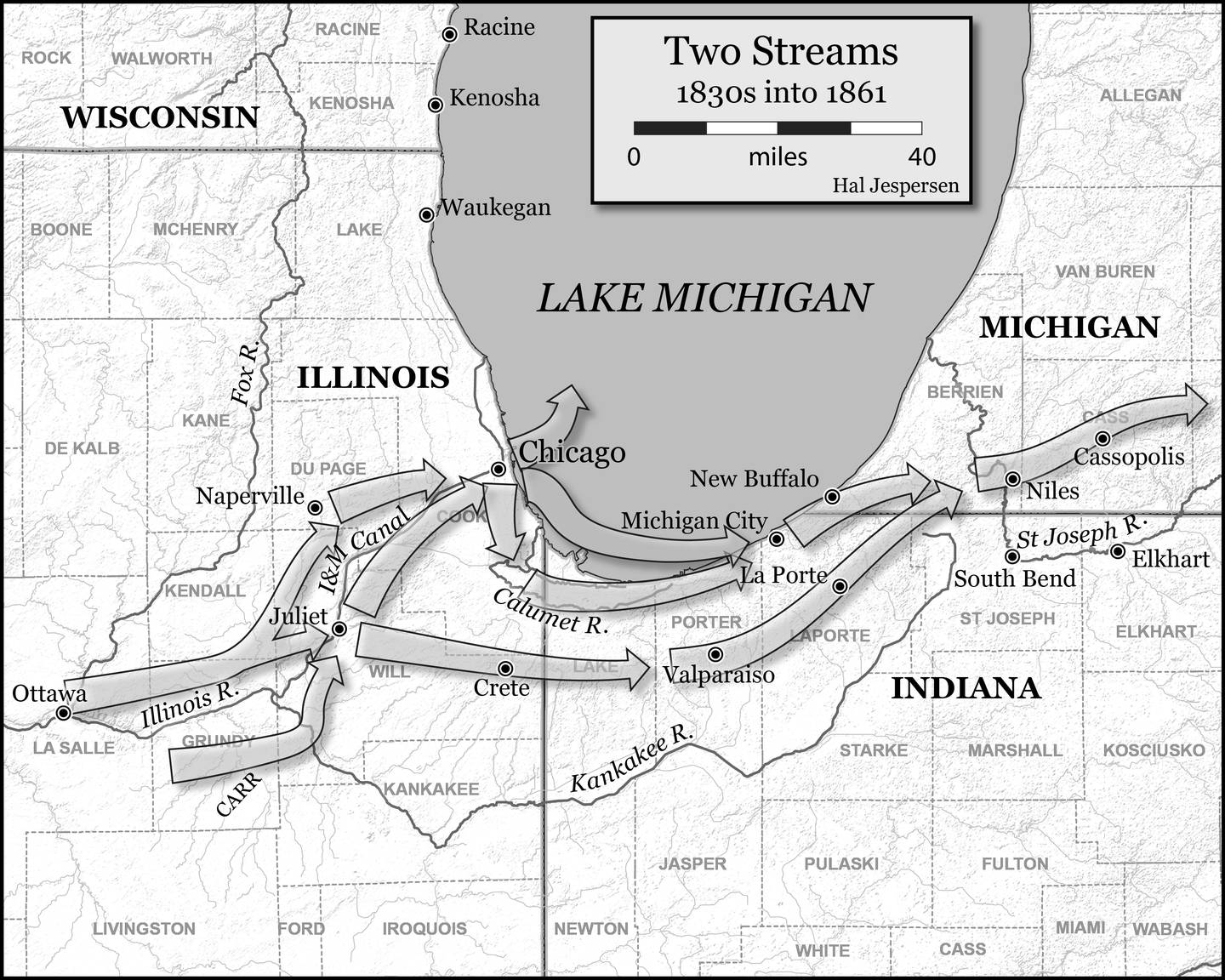

John and Eliza Little walked hundreds of miles from Cairo, the state’s southernmost point, to Chicago in the dead of night. When their shoes wore out, they continued on barefoot.

Years after Berkley Lisbon first escaped enslavement and established himself in Ottawa, Illinois, he was betrayed, jailed and sold back into slavery — only to escape once more. Others fought their way through the legal system, left the country or disguised themselves in hopes for a free life.

As the Chicago Tribune embarked on an in-depth examination of Underground Railroad journeys through Illinois, it became apparent early in our reporting the stories should center around the freedom seekers themselves. While white abolitionists were a vital part of many escapes, evolving beyond their lens changes the narrative, placing it in the hands of the people whose lives and families were stolen — and who gave everything to try and get them back.

“These are not the stories of white abolitionists; these are the stories of human beings, individuals, groups, families — ordinary folks doing remarkable things to seize their freedom,” said Larry McClellan, professor emeritus at Governors State University, who has been instrumental in adding Illinois sites to the National Park Service Network to Freedom register.

Tracing the personal histories of freedom seekers can be difficult, as many were unable to write down their own accounts and relied on others to do so. We selected these seven accounts — several of which are first-person retellings — because they offer a wide-spanning look into the multifaceted lives of freedom seekers who passed through Illinois on their way to better lives. And many, in due course, became history makers in their own right.

“’T isn’t he who has stood and looked on, that can tell you what slavery is — ’t is he who has endured,” John Little said in an interview for an 1856 book collecting first-person narratives of freedom seekers. “I was a slave long enough, and have tasted it all. I was Black, but I had the feelings of a man as well as any man.”

Cynthia Coger

Some might think Cynthia Coger led a quiet life after escaping enslavement. Her first three decades were lived in slavery, during which she married and had children. After her husband died, she bought her freedom and moved to Quincy, Illinois, just across the Mississippi River from Palmyra, the Missouri town where she’d lived since she was 8.

She married a white postmaster and opened a boardinghouse located one block from where an 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debate took place, in what’s now known as Washington Park. Her children led full lives — one daughter, Zenobia Brent, attended Oberlin College, the first in the United States to admit Black people and women. Another, Lucy Ann Clark, married an abolitionist — whose family matriarch had journeyed with “Free” Frank McWorter to become a land owner in Philadelphia — and who took record of a jubilee in Quincy celebrating the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

Emma Coger, 19, took a stand in 1872 when she bought a first-class ticket to ride a Mississippi River steamboat from Keokuk, Iowa, to Quincy. The ship’s captain refused Emma Coger a seat at a table of white women, and she was forcibly removed. She sued the boat company and won in the Iowa Supreme Court.

When Cynthia Coger died in 1985, her Quincy Daily Herald obituary suggested she was cultured, refined and “perhaps the most noted colored woman in Quincy.” It was a quiet life, perhaps, but one richly lived.

Lewis Lemon

In Greenwood Cemetery in Rockford, Lewis Lemon’s gravestone reads: “Born slave — Died free.”

But a lot of remarkable history happened in between.

Lemon was one of the founders of Rockford, the largest Illinois city outside Chicagoland. As a young adult, he struck a deal with his new enslaver, Germanicus Kent, to work for his freedom until he’d earned the equivalent of $800 (or $26,300 in 2023), double what Kent paid for him.

As they traveled from Alabama to Galena, Illinois, the two men met Thatcher Blake, and then together they reached the bank of what would come to be known as Kent Creek in their new settlement named for the rocky river ford. Kent started his lumber mill with Lemon’s help, and six years later, would grant Lemon his promised freedom.

A family granted Lemon a plot of land where he grew vegetables, which he sold from his truck to make a living. He lived freely for almost 40 years, in the town he helped create.

Berkley Lisbon

Each time Berkley Lisbon escaped enslavement, the hardest part wasn’t reaching the free state of Illinois — but staying here.

“Back from the borders of free states, runaways are scarce and no one was on the look out,” wrote H.C. Dickerman in the March, 17, 1888, issue of the Ottawa Free Trader. But in southern Illinois, so near the borders of Kentucky and Missouri, “liberal rewards were offered, which encouraged men to keep sharp watch” for those escaping slavery.

Dickerman’s account is a retelling of Lisbon’s escape from Saline County, Missouri, which borders the Missouri River. As Lisbon worked for Dickerman’s father after finding freedom in Illinois, the writer said he’d “often heard him tell the story” of his flight.

The story began as Lisbon’s first enslaver died, and the man’s son inherited the plantation.

“About this time, I began to think I had as much right to my time as my master, or any other man,” Lisbon said, according to Dickerman.

Lisbon convinced his new enslaver that, rather than lose out on his monetary value if Lisbon escaped, the young plantation owner could sell Lisbon in St. Louis, and Berkley could escape from the purchaser instead.

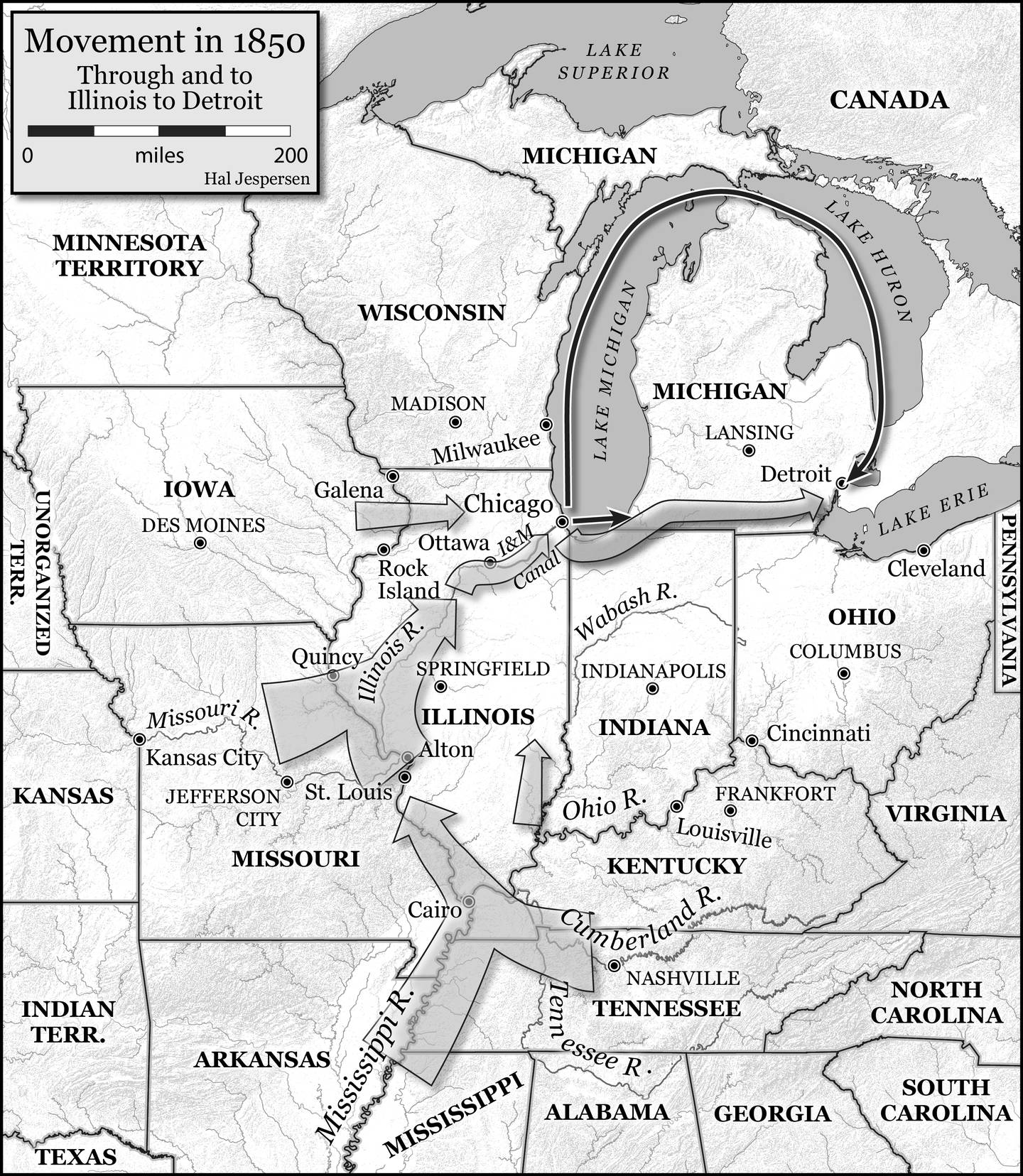

A baker bought him, but quickly sold him to a dealer planning a steamboat trip “way down south — three words that made a (Black person’s) heart ache,” Dickerman wrote. In New Orleans, a sugar planter bought Lisbon, and he finally made his escape, following the North Star over 800 miles through Louisiana, Arkansas and Missouri — a journey that would have taken nearly a month on foot, as he could only travel at night to avoid capture.

Half-starved and exhausted, he stopped at his former home, where two other men joined him, and together they crossed the Mississippi River and made their way to Bloomington, Illinois. The older man they traveled with stayed behind, his feet too swollen and his body too stiff from their long, hard journey. The others followed railroad lines to La Salle and, finally, Ottawa.

After a few close calls during their escape, Lisbon was leery of Ottawa abolitionist John Hossack, who offered to feed and house them. But Hossack ultimately found them work building fences and digging coal. Lisbon made extra money on the side as a talented banjo player, although his street performances led to several beatings.

Around 1859, he joined a group of “fifty-niners” flocking to the Pikes Peak Gold Rush in Colorado, but once they reached Missouri, they had Lisbon jailed and sold back to a slave dealer. But Lisbon, who had once said he would get to freedom “or die in getting there,” escaped yet again, jumping off the steamboat taking him south and swimming to shore before making the hard trip back to the home — and free life — he held dear.

John and Eliza Little

For the crime of going to see his mother 10 miles away, weeks after he and two sisters were sold to new enslavers, 23-year-old John Little was whipped 500 times.

“From the small of my back to the calves of my legs, they took the skin clean off, as you would skin beef,” Little said. After the beating, he was fettered in iron chains around his ankles, which would rub his skin raw.

The man who bought him from his childhood home allowed the 70 people he enslaved just one full meal each day. He would work them into the night, and whip them if they ate during their work. He was known for “breaking” people with the torturous treatment.

But Little would not be broken.

After three months, the enslaver sent him to jail, to be shipped to New Orleans and sold. Little came down with measles, and while isolated from others, made his escape. But after Little hid in the woods near his mother’s home, a free Black person betrayed his whereabouts for $10, and Little was shot as he was captured. He was hired out to work in Jackson, Tennessee, which is where he met Eliza.

Eliza Little, too, was mistreated by the woman who enslaved her. She bore lifelong scars from being struck with broken china plates, wood sticks and tongs. After doing housework for most of her life, she was sold and worked at harvesting cotton. The harsh conditions left her hands blistered, and the hot sun made her sick.

The couple made their flight to freedom after John Little was set to be beaten 300 times with a paddle for speaking to another man during work. John Little hid in the nearby bush and decided to escape, but he had to wait for his wife to recover from an illness. During his wait, their enslaver found out about the plan, and he tied and beat Eliza for information on her husband’s whereabouts. She refused, and as a blacksmith made shackles small enough to fit her, she slipped away to find John.

The pair would continue their escape, but not without meeting confrontation, inclement weather and a lack of resources. The Littles crossed the Ohio River to Cairo, Illinois: “Don’t you think we’ll drown?” she asked. “I don’t care if we do,” he said.

They walked through Illinois to Chicago, traveling by night for three months. “My shoes gave out before many days — then I wore my husband’s old shoes till they were used up. Then we came on barefooted all the way to Chicago,” Eliza Little said. “My feet were blistered and sore and my ankles swollen; but … there was something behind me driving me on.”

Eventually, they made it to Chicago, got funds from abolitionists to head to Detroit, and then crossed to Windsor, Canada.

They settled near Queen’s Bush, Ontario, building a log cabin and farming successfully. By 1855, they would have 150 acres of land, fields of wheat and potatoes, and horses, oxen, cows and sheep.

“If there is a man in the free states who says the colored people cannot take care of themselves, I want him to come here and see John Little,” he said.

They also got the chance to share their stories, told in their own words. That year, journalist Benjamin Drew interviewed dozens of Black Canadians, most of whom were formerly enslaved Americans who sought freedom in the north. In his resulting book, “A North-Side View of Slavery,” he shares interviews from the likes of Harriet Tubman, the Littles and many others.

Mary Meachum

Each year, on the banks of the Mississippi River, hundreds of people gather in St. Louis to celebrate rarely told Black history (this year, the Oct. 14 event will focus on Black music history and the 50th anniversary of hip-hop.).

The Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing Celebration, like the Network to Freedom site where it takes place, is named for Meachum’s 1855 attempt to help at least eight enslaved people cross the river into the free state of Illinois.

At that point, Meachum was about 50 years old and had dedicated her life to freeing and educating Black people. She and her husband, John Berry Meachum, were both born enslaved, but he used earning from carpentry and saltpeter work to buy their freedom. Over four decades, they bought the freedom of 22 enslaved people and hired them to work, taught Black people at a time when Missouri banned all such education, and helped them escape to Illinois.

Before dawn May 1, 1855, Meachum led her namesake crossing, but they were ambushed by armed police and slave catchers on the Illinois shore. Most of the enslaved people were recaptured, and Meachum and her fellow abolitionists were arrested. In her final decade of life, Meachum cared for Black soldiers and formerly enslaved people as president of the Colored Ladies Soldiers’ Aid Society.

James Salter

James Salter was living just 75 miles south of Chicago in 1860 when he was one of three Black men kidnapped from Clifton, Illinois, and forced at gunpoint onto a train to Missouri.

The two other men were whipped and starved, but would not say they belonged to any enslaver, and subsequently were sold south. Upon questioning, Salter acknowledged that he had fled five years earlier from a farm just outside St. Louis. His former enslaver, Aime Pernard, paid $100 for his return.

But two days later, Pernard set Salter free, and bought him passage back to Clifton.

“James … out to have known that he had no reason to fear my course had he frankly avowed me to his wishes to settle in Illinois,” Pernard wrote in a letter printed in the Chicago Tribune. “Although I have often been told of his whereabouts, I never took the slightest steps to recover him, concluding that if he thought he could do better elsewhere than with me, he was welcome to the change.”

A group of Clifton women, who wrote to Pernard and included his account in their Tribune editorial, noted that “Though before one of the truest and best of men, (Salter) has gained new and admirable qualities in the exercise of the right to own himself. He feels that he has a new character to sustain — that the responsibilities of freedom are upon him.”

Henry Stevenson

Henry Stevenson’s lively spirit is evident from the first moments of his interview with an Ontario researcher in 1895. He cracks jokes and insists he’s 104 years old.

During the California gold rush, enslavers asked him to find two people who had escaped enslavement near his Audrain County, Missouri, home.

During Stevenson’s first night on the road, a Black woman at the public house where he stayed asked him about the two freedom seekers and what he had planned.

“I told her ‘to go with ’em if I could find ‘em,’” he told the interviewer. She told him she was a fortuneteller, and “she said, ‘I’d never go back anymore,’ and sure ‘nough I haven’t been back.”

In Quincy, Stevenson was sent to hunt for the escaped pair, and the wife of a free Black man told him there were people who could help him get to Canada, “the first time I ever heard of Canada,” he said. But he returned to the enslaver he was helping, and together they traveled to Peoria, then on toward Chicago.

Underground Railroad conductors continued to approach Stevenson, encouraging him to leave his enslaver and seek freedom. Finally, one told him to board a different boat than his companion, and Stevenson took the plunge. Another abolitionist gave him money and extra clothes, and he traveled to Detroit before landing in Windsor.

His likeness is immortalized — along with fellow freedom seeker William “Bush” Johnson, who passed through Indiana’s Lafayette and Michigan City en route to Canada — in Wilbur Siebert’s book, “The Underground Railroad From Slavery to Freedom: A Comprehensive History,” originally published in 1898. In a photo, “A Group of Refugee Settlers, of Windsor, Ontario,” the two men sit side by side in front of three other freedom seekers, perhaps unaware of what they would find in the Canadian province.

They both stayed there, living freely, for years to come.