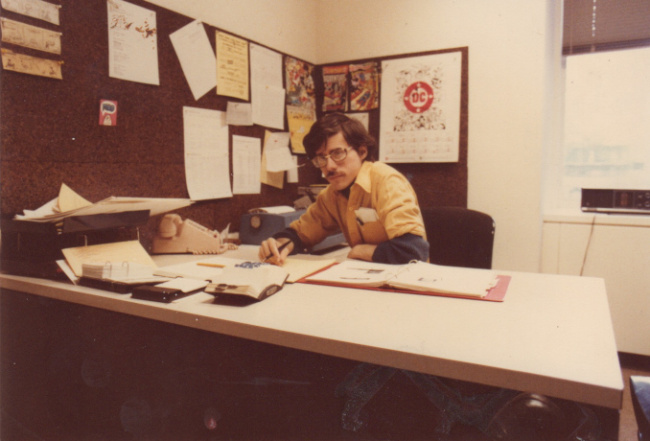

Paul Levitz had a long career at DC Comics, starting out as a freelancer when he was still in high school, rising through the ranks to President from 2002 to 2009, and retiring in 2010. During that time he had an active hand in shaping the Direct Market as well as the comics sold there. In Part 2, he talks about the rise of the Direct Market in the 1980s and how DC tailored its content for this new audience, leading to the creation of the Vertigo imprint. Part 1 focuses on Levitz’s early years, starting when he launched a fanzine at the age of 14 that brought him into contact with creators, retailers, and Direct Market pioneer Phil Seuling. In Part 3, he discusses how Image changed contracts with creators, how Marvel Comics’ purchase of Heroes World changed distribution for DC, and how he thinks comic shops will evolve in the future.

To watch a video of this interview, see “ICv2 Video Interview – Paul Levitz, Part 2.”

This interview and article are part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see “Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary.”

How did your role change then through the ’80s? You said you came inside on the editorial side but became the business guy. How did your role change?

In ’81, Jenette became president, Sol retired, and I essentially became the chief operating officer of the company, which is pretty ridiculous. I was 24 years old. This was a division of a Fortune 500 company, but the corporate management didn’t value the DC properties or the DC business particularly.

Jenette and I had a good working relationship. She believed in me. I had a little bit of business training. My schoolwork before I dropped out was towards a five‑year bachelor and master’s in business program, so I’d taken basic cost accounting, this and that, marketing, management. I had more business knowledge than anybody floating around the place.

I liked doing the things she didn’t like doing. The essence of our teamwork over the years was, she’s an incredibly smart but very project‑focused person: “Give me a thing to do and I will get that thing done no matter how impossible it is.” I love detail. I love managing, I love making systems work, and I was perfectly happy trying to figure out, let’s figure out how to make this a profitable business. We had a lot of fun through all of it.

The title changed a bunch of times, and we bought out our international rights agent. We started our own licensing department to manage that system better, to create style guides, to use the art in a more disciplined and better fashion. Started our own marketing and sales. DC didn’t have anyone selling their comics prior to that.

I looked up the year, I think Camelot 3000 started in 1982, and that was a big change in package for comics and seemed very much focused on the Direct Market. Can you talk a little bit about the decision to make that publishing change?

For many years, there seemed to be no alternative to World Color Press and their ancient letterpresses that were printing pretty much all the comics in America. Around 1981, the technology on offset became better for shorter runs. It was predominantly a change in the plate making that may have made the difference, and the setup became a little bit simpler.

For the first time, we had offset printers showing up saying, “We can do what you want.” Marvel moved first in that. They did a Starlord Special with a company called Ronalds that was a Canadian printer that was showing its stuff around. As soon as these guys called on us, we said, “Yes, this is an opportunity.” We were trying to develop our first titles to go strictly to the comic shop market so that we wouldn’t have to use the Comics Code (we could do somewhat more mature material), maybe there’s a way of making the books look a little better. We loved the idea of the offset, so we went with that. I remember being up about midnight as we were doing the press check for the first issue of Camelot up in Montreal as that was rolling off, watching it come together.

We had done, I think, two prior experiments in things direct only. One taking a reprint book that we had put together for Random House for sale at school book fairs and making it available just to the Direct Market, not to the newsstand market. Then we had done an issue of the character Madame Xanadu as a one-shot for the Direct Market. Both of those experiments had done relatively well, obviously the original thing doing much better.

DC was not a strong brand for the Direct Market at that point. We weren’t producing a lot of material that was aimed for it. We had a lot of war comics and mystery comics, kid‑oriented stuff. Camelot 3000 was very clearly focused for that, and we saw the opportunity to make it a better-looking product, a little higher priced, and maybe make some successful noise.

This is obviously a big change from the period you talked about earlier where, well, there’s these fans out there, but they don’t really account for very much of our sales and really we’re a kids publisher. How did that change in target audience and approach and the importance of the fan market change?

By the end of the 70s, it was clear that the newsstand system in America was degenerating, not just for comics, but for all forms of magazines, comics being the weakest part of that system. We were bleeding badly. The direct stores were increasing in number, still a fairly small number, 500, 700 maybe at that point. They seemed to be growing, and they were growing without a lot of support. We were still selling them cash up front, for example.

One of the first things I did when I moved to the business side of the company, again, working with Jenette, but I was the guy on point with it, she brought in a very experienced distribution consultant, a guy named Leon Knize, who you may have met back in the day. He designed all sorts of distribution systems in his career, Coats & Clark Sewing notions and the earliest rental plan for the home video business.

He did what consultants do. He dived in, he talked to newsstand distributors, he talked to comic shop distributors, he talked to comic shop owners, and he came back and supported the instinct that Jenette and I had, but he was more credible with our bosses at Warner Publishing. He said, “No, no, these kids are right. This end of the business is not going to serve you in the future. This end of the business can be grown and you should do some things to make it grow.”

We worked together for a number of months designing a credit plan that you may remember, or you may still have some scar tissue from, to serve the direct distributors and say, “Yeah, we can offer you credit, but we’re going to do it in a fashion where we’re going to be highly confident we’re going to be the first company paid. We’re not going to have to worry about bad debt very much.” That was a very successful plan and program over the next batch of years. Our sales to the Direct Market, I think doubled in the first year we had that in place.

Which was which year?

’81 to ’82, probably.

Yeah, that was right about when Capital City signed on. We were direct with Marvel first and buying our DCs from Russ Ernst, and then we went direct with DC at some point right around there.

Is that the point at which you started dealing with the direct distributors yourself?

That would be the point at which I; at that point, I was pretty much the face to it because we hadn’t yet built up our marketing department. I lived in that world for the next couple of decades.

Who were the key distributors in the early ’80s?

I’m not sure that you could phrase that any one individual was key at that point. Phil was weakening. He probably still had the largest share. There were two brothers, the Schusters, who ran a company called New Media/Irjax that had a large volume but a very flimsy distribution structure that was clearly not going to survive for a very long time. Bud Plant was on his own. Russ was on his own. We weren’t selling to Chuck Rozanski and Annette directly. Walter Wang and Ron Forman with their Comics Unlimited, I think Diamond was a sub‑distributor of theirs at that stage. Diamond hadn’t gone direct yet when we started. There were about ten. Ron Van Leeuwen with Andromeda, I think, was already direct at that point and something called MultiBook, also in Canada.

Then through this period in the early ’80s, that channel is growing. I assume newsstand is shrinking or at least shrinking in share. How did that phenomenon manifest itself in terms of the growth of direct and the shrinking of IDs in importance?

Well, for DC, you start seeing our line change. We start dropping out even some titles that are profitable but were totally aimed at the newsstand because we know they won’t be profitable in another couple of years. So the mystery books start disappearing. The war books start thinning out. We’re introducing instead more titles that are from a content standpoint aimed at the audience that we’re seeing in the comic shops.

We begin to reformat some of the books to serve that audience better. We shift Teen Titans and Legion, our two most successful ongoing titles, to the Direct Market over into offset side. We begin, and this is enormously to Jenette’s credit, she goes talent hunting. Frank Miller is the most interesting talent in the business. She manages to bring him over to do Ronin. It’s over‑ordered because it’s a little more experimental than the market is really ready for. The market’s kind of basing their numbers on his success in Daredevil, so they were a little battle-weary after that. Frank goes back, does some more Daredevil. Then she brings him back to us to do Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and has the courage to sign off on his doing a really radical, different approach to Batman at that point.

She also puts a lot of energy into recruiting a lot of the British talent who start coming over at that point. That leads to interesting things like Watchmen along the way.

I mean, ’86 was a really incredible year at DC with both Watchmen and Dark Knight. It sounds like that was, Jenette’s out there hunting talent and bringing them in and giving them the freedom to do that kind of work, which was definitely revolutionary for comics at the time, or color comics at least.

Absolutely. She’s bringing them in. I’m figuring out how to do a contract that might appease them and make them interested and be more appealing than alternatives that are out there at that point. There were a few beginning independent publishers that were offering interesting, competitive things but not yet large‑scale competitors in that scale.

We were trying to make the deals better and more reasonable. “Can we give you your own copyright on Ronin, Frank? Can we build a contract that has better participation, reversion clauses, different things that make it a more attractive proposition?”

You were working on that side of things. Was that in response to, you mentioned Pacific Comics was around, I think Dark Horse Comics started around maybe ’84, ’85, somewhere around there.

Something like that. Pacific, First.

Right. Oh yeah. First was early ’80s. You were responding to competition from these upstarts that were trying to get talent by giving them more rights or more compensation?

The basic business plan was to say, “Look, we’re a creative company that works in comics. What can comics do that we can market and sell successfully? Who is our audience? Our audience is changing, how we sell the comics is changing. What’s the opportunity? How do we pursue that?”

Competition was a part of it, but the main part of the competition was Marvel. They were the dominant publisher in the Direct Market at that point. I remember writing a strategic plan in the early ’80s, when Marvel had about an 80% share of the Direct Market, that said, “We’re going to do X and Y, and I think we’re going to get ourselves to meet Marvel somewhere in the low 30s.” The rest is going to end up going to all the other guys. In fact, that proved to be the case. That’s not because I was brilliant, it’s because we could see the path of what the opportunity was.

It might not have worked if we didn’t do our job well, it might not have worked if Marvel had done their job better during those years, or if one of the independents had been well‑financed and done something wonderful. That very business plan, a decade before, included an acknowledgement of the possibility of what became Image Comics, the idea that at some point somebody’s going to come up with the United Artists approach to the comic book business, and that will be an interesting business problem for us when that happens. We were expecting it to be Simonson and Starlin and Chaykin who would do it rather than Lee and MacFarlane, but it took a little bit longer.

The audience, you spoke about the difference between the fan audience and DC’s target audience in the ’70s, which was a big gap, but that fan audience seems to still be evolving in the ’80s. Can you talk a little bit about that, in terms of demographics and who was buying?

Well, as far as we could tell, we were dealing with an audience that was 16 to 25, by and large. Well educated; something like 15% of our audience was getting graduate degrees, which is a really high percentage for the United States at that point. Fairly prosperous. Mostly urban, college towns.

You couldn’t run a comic shop in a small town in the middle of nowhere. There wasn’t enough foot traffic to make it work. Of course, you didn’t have the Internet to connect people or to sell your books and ship them easily. The dynamic changes enormously when the first of the Tim Burton Batman movies comes out. That about doubles the size of the whole Direct Market in a year.

It was 1989, right?

Yeah, June of ’89. For a variety of reasons, we had been developing a Batman movie for quite a number of years without a success of getting it out there. As a result of the length of the development, we had not managed to have as robust a licensing program as you might have expected around Batman.

The comic shops actually were the best Batman headquarters. We had a little bit of stuff in the Walmarts, Targets of the world, but not as much as we would have in a later year. The comic shops benefited enormously from the fact that suddenly Batman was this giant cultural phenomenon again.

We were getting in at Capital City pallets of Batman sneakers, all of the swag, T‑shirts. There were tons of T‑shirts, so there was definitely a lot of merch flowing into the comic stores. You talked about the age, income, and so forth. What about gender?

It was all men. This is not to say there were no women coming into the comic shops, but statistically speaking, it was all men. We weren’t putting out product that largely went to a female audience at that point.

The women who were coming into the comic shops were women who were interested in the same kinds of material that the men were interested in, and that was a fairly small percentage.

Was the kids’ audience also, back in the ’70s, was that overwhelmingly male as well?

Nobody did any market research in the ’70s. As best I could tell, it was not a heavily gender weighted period. The mystery books certainly were selling very well to the young girls, and of course Archie always was selling well to girls. Harvey was selling well to girls at a young age. I would think that Little Lotta or Little Dot clearly were going to girls, not going to guys.

Why was this Direct Market so heavily gender-weighted toward male?

There’s a concept in marketing called product lifecycle, and it defines to some extent that certain behaviors are a natural curve at different stages of product introduction. The newsstand market was disappearing. Essentially, the product that we were introducing in the comic shops, we, the publishers, DC, Marvel, the independents, Dark Horse, had a new set of characteristics. The price was higher. It was no longer what’s called a convenience product, it was now a shopping good. You had to want to go to a damn comic shop. This was a conscious decision. You were going out of your way for it. It had to be important.

The products that were initially developed for that came out of the lines that existed largely based on the culture of Marvel Comics in the ’60s and ’70s, and that had been a very male‑driven line.

The first comic shop owners were almost all guys who had grown up around Marvel Comics and who were starting comic shops because they didn’t want straight jobs. They didn’t want to have to wear a suit and tie. They wanted their own business. “If I open my little comic shop, I can talk to people about comics all day. I can open at 11:00, I don’t have to open at 9:00. I can stay open late. It can be a nice place.”

A lot of them were really wonderful human beings, many of whom became dear friends over the years. Their first goal in life was, for most of them, not to get rich. It was, “I want to be surrounded by the things I like, and I want to share that with people I like.” The things they liked initially were Marvel Comics.

You had moved up in the executive ranks, so had some visibility upward in the corporate structure. Who was DC reporting up to during the ’80s? Were you getting the support to develop this Direct Market in the directions you were taking it?

We were very lucky in who we reported to. Bill Sarnoff, who I mentioned earlier, was the guy DC reported to from about 1971 or 1972 to 1989, straight through that whole period. Then we shifted over to being part of Warner Brothers. At that point we reported to a guy named Sandy Reisenbach, who also was a good guy and very supportive. We reported to him from ’89 to about 2000, 2001.

Is that the result of, or in preparation of, the Batman movie? The timing is interesting.

It’s a combination of the Batman movie and the Time Warner merger, which made a game of 52-card pickup with the different divisions. The transition was—I’ve used this metaphor before: We went from being part of a small, poor kingdom where anybody could go talk to the king, and if you had a good idea and it was within the reasonable resources of this little kingdom, great, you could do it. That’s what it was like working in Warner publishing. And we went to being part of Saudi Arabia where there was more money than God, and on any given day, you had to figure out which combination of sheiks had to approve what your idea was, but if you could get the right group to approve it, the resources were unlimited.

When we started working for Sandy, he was an old advertising guy, he came out of Grey Advertising and his first thing was, “You should have TV advertising for comics. Why not?”

“OK, boss.”

He hooked us up with a couple of different advertising agencies in sequence, and we spent tons of time testing and researching and developing to come to the conclusion that it was absolutely economically impossible in the market as it was then structured. First you have to explain, by the way, this thing called comics, or they weren’t really, nobody knew what a graphic novel was, if you called them a graphic novel. This is something that most of you have already decided that you’re not interested in, but you really should be interested. And then, would you go to your phone book, in the old days of the yellow pages, and try to figure out where there’s a place that actually sells them that you’re willing to go to that’s out of your way, that you have to specifically go to get this thing. And by the way, you have to pay a lot more for it than you think intrinsically that this product is worth, based on the imprinted knowledge you have of what a comic book was maybe when you were a 10‑year‑old kid 10 years ago.

Yes, you could get more people to do it, but the more money you spent on advertising, the more money you would lose. At least we learned it being analytical rather than the hard way, by throwing money at it that would not pay off. But we got terrific support by and large over the years.

You mentioned book format products. That was also happening beginning in the late ’80s, is that right?

One of the things that was on my personal agenda was that, again, talking about the 1970s, if you walked into a record store, you could get Beethoven or The Beatles. If you walked into a bookstore, you could get Agatha Christie or you could get John Grisham.

We’re talking about dinosaur age from the point of view of a lot of the people listening to this, obviously. If you walked into any place that sold comics, you could get this week’s comics, maybe this month’s comics, or you could pay some ridiculous price for a dusty old copy if you could track it down.

All of the instrumentality that exists for being a collector these days, the eBays of the world, and the Internet of course, didn’t exist. I wanted to find a way that the best of what comics had done would continuously be available. I tried a couple of experiments, as I had some business responsibility to try to do that, the first couple of which failed miserably. I didn’t come up with anything that made any sense relative to the marketplace.

Then, finally in the mid‑‘80s, when we had the success coming with Dark Knight, we saw an opportunity to really work with the book format. There had been trade paperback collections of comics before. We didn’t invent the idea. Jack Katz’s First Kingdom, I think, is the first time anybody did a graphic novel sequentially reprinting a comic. Apparently, nobody read it, but it was a noble effort by Simon & Schuster back in about ’78 or so. Dave Sim had done his little black and white phone books of Cerebus. There had been major book publishers that had done nostalgia‑oriented collections of Marvel and DC comics over the years. Superman from the ’30s to the ’70s, origins of Marvel comics, things like that. Some of them had done fairly well. But nobody had really tried to say, “This is a comic book to be read. This is a reading experience in book form, not a nostalgia thing, not a collectible thing.” We marketed Dark Knight that way.

We made a unique deal with Warner Books, where we took the risk for both marketplaces. They were our co‑publishing partner, and they brought it out to the bookstores. We got a large number out there. Did that with a sequence of books over the next few years.

Really, it was with Sandman that we turned the tide because that was the first time that it behaved like a book. Y ou put out a new volume of Sandman, all the previous volumes started selling. Neil [Gaiman]’s work connected with a wider audience, connected with a lot of women for the first time in our line. We saw the demographics of the audience began to shift. That worked well for the bookstore because more women went into traditional bookstores than guys did.

Karen Berger was the editor?

Yeah.

Let’s talk a little bit about her role and then going up to the founding of Vertigo as a separate imprint.

I hired Karen as my assistant in ’80, I think, when I knew I was shifting over to the business side. I wanted her to take over. I needed someone to take over the responsibility predominantly for managing the freelancers. I was responsible for freelancers’ schedules for about five years prior to that. I was looking for someone who didn’t really have a deep comics background but just had the organizational skills and publishing skills.

She was a kid fresh out of college. She’d done an internship at Omni, the early science fiction magazine of that period. A friend of hers, Marc DeMatteis, was a comic book writer. He recommended her; we gave her a shot. She very quickly developed into a real editor. We could see editorial potential. She started on our mystery books. She began doing some experimental things, Angel Love, Amethyst.

Essentially, Karen wanted to do comics she wanted to read. She wasn’t enormously interested in the superhero stuff. It was OK, but it wasn’t her flavor. She wanted things, for lack of a better term, I’ll say that were more literary, that were more emotionally driven. She did a great job on Wonder Woman, working with George Perez, still I think probably some of the best issues of Wonder Woman that we’ve ever done. She was very successfully working with me on Legion when I was writing Legion of Superheroes. She began particularly working with the British talent, doing more and more books that appealed to an older audience. That worked in the comic shop, didn’t work for the newsstand. That pushed us out of the code. Swamp Thing with Alan Moore.

After a few years, the office joke was that that was the Berger‑verse. Those were the books that sort of all had a tonal similarity. We realized that there was an opportunity to make it into an imprint and called her in and said, “What do you think?” and that turned into Vertigo, which is one of the proudest things that I had any kind of hand in. Karen really is the heart and soul of what the success of Vertigo was.

At its peak, Vertigo was the third or fourth largest comic company in America. It was larger than Dark Horse. Nobody saw the statistics that way because they weren’t available, but the paperback side of the company was enormously successful. The creative quality of it was extraordinarily high. She did a fabulous job.

Click here for Part 3.