I grew up in Thousand Oaks, California. The palm trees were tall, Malibu was a 40-minute drive down Route 101 and the population was less than 2% Black. Meanwhile I was 100% Black. I stifled my Blackness with keratin treatments that straightened my afro, frilly clothing that cloaked my athletic build and white pop culture that applauded the antithesis of my identity. My only non-white influence was my biggest secret: anime.

Although technically a Japanese art style, anime in the West colloquially refers to Japanese animation with vivid graphics, distinctive characters and fantastical themes. I became infatuated with the genre-not-genre when I was 10. Watching just one episode of Naruto with my older brother after soccer practice had me hooked. In hindsight, it wasn’t the show’s melodramatic fights or thought-provoking plots that made my heart race; it was the rush of rush of representation. The villains had voluminous hair, side characters popped with main character energy and the protagonist was often a child with the odds stacked against him. It was both captivating and confusing. Naruto Uzumaki, a 12-year-old ninja from Japan, neither looked nor sounded anything like me but his essence reminded me so much of…me. Or at least, a version of me that I wanted to be. He was my hero.

The heroes of my peers, on the other hand, were Miley Cyrus, Justin Bieber, Taylor Swift…the Eurocentric list went on. I loved watching the Disney Channel and listening to Swift’s “You Belong With Me” as much as the next teen but Naruto’s desperate need for societal acceptance, camouflaged by his unabashed optimism, spoke to me more.

Misogyny and racism ran rampant within the Western anime fandom of the early 2010s (unfortunately, it still happens to this day). Online forums openly sexualised underage characters, Tumblr users harassed BIPOC cosplayers and many series contained inappropriate motifs. The thought of being associated with such a toxic fandom made me fall in love with my Japanese cartoons in silence. I couldn’t comprehend why I loved this gory, masculine series as a Black American girl aspiring to white femininity. Despite the shame I felt about my interests, I never missed a new episode of Naruto with my brother. I found myself addicted to that one hour of Toonami after soccer practice not just because the story lines entertained me but because they validated my traumatic experiences.

Japanese animation influenced other Black women’s lives as well. “Anime is something that has stuck with me since I was literally a child,” Mimi, a longtime favourite Black cosplayer of mine, told Refinery29. She refused to let the lack of Black characters in popular series and the aforementioned racism within the anime community limit her artistry. Instead, she let the love from her fans outweigh the hate. “Fast-forward a few years and my favourite anime to this date remains Nana and Hunter x Hunter. In terms of fashion, Nana Osaki is literally me.” Getting Animated podcast host and avid anime fan Destiny Leclerc shared a similar relationship to the art form. “The one that really changed me and made me into an anime fan was Peach Girl,” she revealed to me during a lively phone conversation. The series followed the life of Momo Adachi, a 15-year-old Japanese high school student who was mistreated by classmates because of her tanned complexion. “I was 14, I lived in Florida,” said Leclerc. “[Momo] is like, This boy that I like doesn’t like me because he doesn’t like girls with dark skin! I was like, Ugh! She’s just like me for real.”

During my teens I leaned more toward male-focused shonen anime and manga — an anime category traditionally made for boys ages 12 to 14 — so I never acknowledged the visual similarities between characters and myself in the way Leclerc and Mimi did. That is, until I moved to the first Black neighbourhood I ever lived in: Crown Heights, Brooklyn, New York.

I was 22 and a new graduate from the predominantly white University of Washington. You could smell the white suburbia radiating off me as I sat on a bench in Prospect Park and people-watched. Many of the Black women of Brooklyn rocked brightly coloured hair, long acrylics and flashy outfits on a casual Tuesday afternoon. They spoke with their chests and were the stars of their own stories. Something clicked: These Black women were the shonen anime protagonists I had idolised for years.

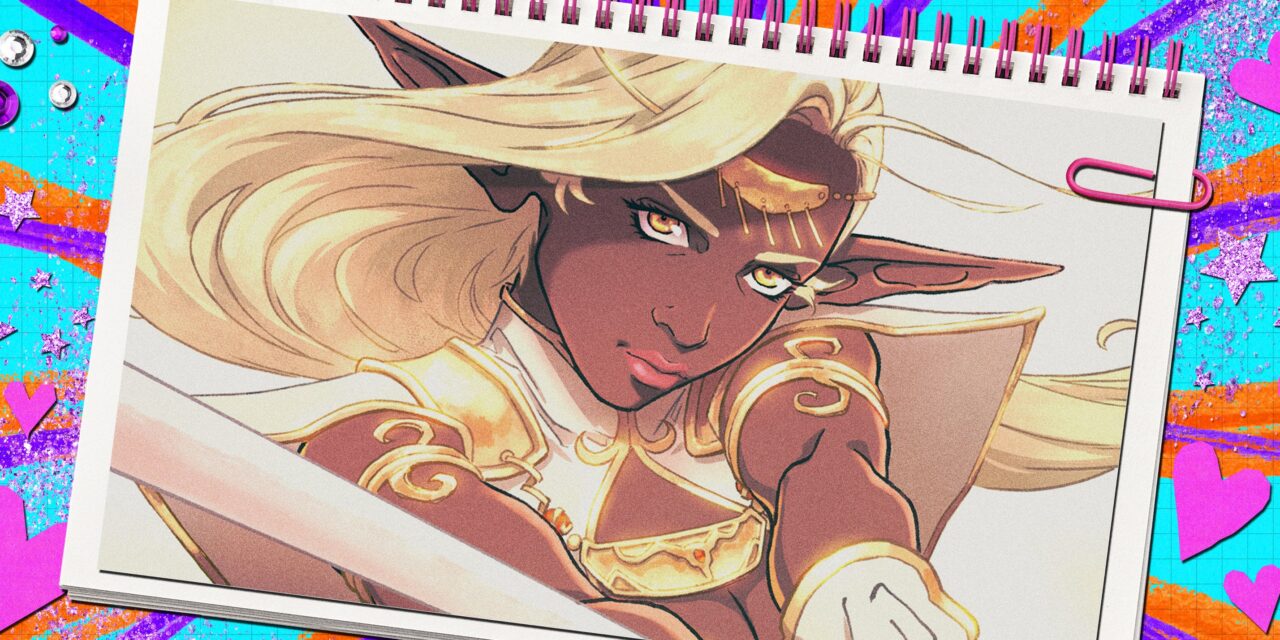

Who are shonen anime protagonists? They’re the most underestimated characters in the series. They have amazing, unique features — whether it’s bright blonde hair, dark skin or unshakable resilience — that stick out. More often than not, these protagonists come from broken homes and are looked down upon by society for things they can’t fix. They’re forced to grow up faster than any child should. They work 10 times harder than their peers because of systemic oppression. Despite all this, they triumph.

“A lot of the stories in anime specifically were a lot darker than what we would see on regular TV,” said Lerclerc. “When I talk to my husband or other Black men about Dragon Ball Z, for example, it’s the father aspect of it. It’s the brotherhood of it all, like with Vegeta and Goku [characters in the series] going back and forth. There’s a lot of parallels with that in our community.”

Naruto was the first show I watched that was for children but didn’t treat me like a child. The main character was a neglected 12-year-old orphan facing relentless discrimination by his village because of the demon fox sealed inside him. I was a 10-year-old girl whose classmates groped and grabbed my hair because my locs were “weird”. My camp counsellor called me “Buckwheat” that year because I, the only Black kid at camp besides my brother, reminded him of that character from the movie The Little Rascals. American television could overlook racism and oppression all it wanted to but I still lived it when I turned the TV off. The censorship failed me. It failed all minority kids looking for an answer as to why they were treated differently.

“I have noticed some similarities with some of my favourite characters, mostly being that they are also quiet but throughout the series, show their strength and are extremely reliable,” prominent Black cosplayer Bria B. told Refinery29. “As for backstory, some of my favourite characters have challenging childhoods which caused them to be quiet or anxious in the present. I can sympathise with this. An example would be Crona from Soul Eater.”

Sitting on that Prospect Park bench that day, I felt like Light Yagami getting his memories back in Death Note. If you’ve never tuned into the hit animated thriller, I experienced a jolt of shock followed by a calming wave of understanding throughout my body. Naruto Uzumaki, Gon Freecss, Ichigo Kurosaki — for years these characters echoed a Black experience I hadn’t yet validated and hinted at a culture that I had craved since birth.

Of course my Black mother was my muse and I had access to Black media. I also had severe internalised racism throughout my adolescence and an intense fear of ever acknowledging my 100% Black self. I panicked every time I flipped through the Essence magazines my mom bought me or tuned into Black Girls Rock! on BET (Black Entertainment Television). I felt like I could survive mentally in my white neighbourhood only by severing ties with the Black representation available to me and by suffocating any remnants of my Blackness in my being. Let’s call it self preservation. At the time, I could process my own identity only through the veil of animation and fictional boundaries. I needed my representation to be watered down.

The 22-year-old Black woman on that bench that day was determined to be her full Black self. I had robbed her of her identity for two decades. Being unapologetically Black was the scariest concept in the world to me (quite frankly, being unapologetically Black in America can put your life in danger). But the Black community around me acted as though there were no other way to be. In that moment I knew why I gravitated towards the casual extravagance and empowered demeanours in these animated alternate universes. Suddenly I knew why “kids’ shows” like Inuyasha made me bawl as a 19-year-old. They satiated and affirmed a part of my Black identity that was begging to be nurtured. Meanwhile, Brooklyn brought it to life. Local BIPOC events welcomed me when I came alone, murals from queer Black artists embellished every block, Black trans women spearheaded Black Lives Matter protests, my Black women’s therapy group affirmed my childhood troubles, and more. To put it simply, I finally learned how to love myself.

It’s been three years since I began celebrating my existence with the help of Brooklyn’s Black culture. I spent my first few weeks traversing New York City with plain, straight hair, simple outfits and subdued makeup. Today I have kanekalon down to my butt, nails inches past my fingertips and a loud wardrobe I’d never wear in the suburbs. Today I’m 26 and — I say this with confidence — my own anime protagonist.