It was a warm day in SF when I stopped by the Museum of the African Diaspora. I hadn’t been by since they relaxed their COVID protocols (masks are now optional.) As I walked around the building’s Salon space, there were two older, unmasked white women there. Both were rambling about how the Smithsonian-associated MoAD is “nothing” compared to the proper Smithsonian. I silently lamented the presence of more mouth-breathers who were in my hometown just to complain about how they’d rather be someplace else.

Fortunately, my purpose was worth putting up their kvetching. MoAD’s Salon is currently showing the Oakland-based Nimah Gobir’s “Holding Space” (through August 20) curated by Selam Bekele, in which the question of “what makes a place into a home?” is central.

Largely showcasing Gobir’s work at the Johansson Projects, “Holding Space” is a collection of oil paintings on canvas accentuated with thread. The pieces are slice-of-life images (possibly based on photos) in which the subjects (mostly Black women) occupy environs in which they seem most at ease. Whether it’s the simple caress of a (teenage?) seaside couple in “Lake & Paradise,” or the artist’s own mother strolling in a red dress through her home in “Cole Ave 2,” the show displays, for lack of a better term, a “nesting” theme.

Most of the collection consists of Gobir’s “Tender Headed” series, depicting subjects having their hair braided. The unbraided hair is painted on the canvas, whilst the braids themselves are a kaleidoscope of colored threads stretching from an image on one wall to an image the next. It’s funny how tangled threads from several different paintings can trigger a visceral memory that makes the series title all the more real.

The main focus of the exhibit lies with the paintings “27” (the age of Gobir’s Nigerian parents in the image, who are depicted before she was born) and “Xalapa” (featuring the artist and her partner seeming trying to recreate the former image whilst in the Mexican city.) “Has our notion of home changed across generations?” she asks in the accompanying text. “What does it mean to be 27 today?”

The answer to the first question is obviously “yes,” though Gobir’s paintings do seem to lose details in the chosen medium. For instance, “Cole Ave 2” has text saying that Gobir’s other paintings can be seen in the lower-right, but you’d never know at a glance. Had these remained photos, those details would have been easier to find, and elements of each “nest” would have been easier to connect. Gobir is a fine painter and her embroidery touch is inspired, but the beautiful abstract element of oil—though lovely and dream-like—removes some of the exhibit’s more visceral impact.

—-

Coincidentally, I next made my way over to Yerba Buena for another exhibit that revolves around women of color and their perception of “home.”

Sponsored link

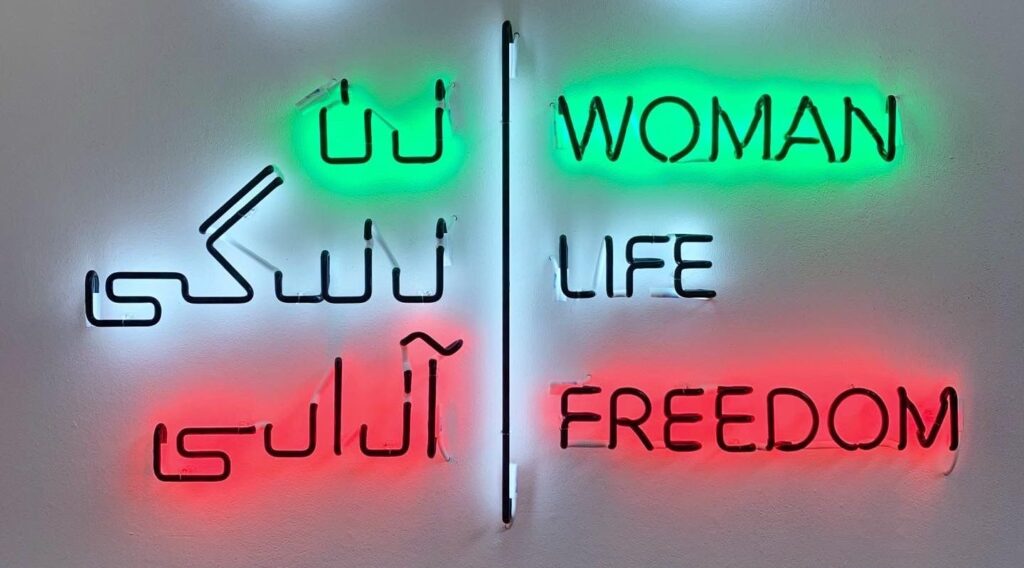

Despite YBCA’s lax COVID rules, I’d been meaning to see “طراوت | TARAVAT” before it closed on July 23, but life gets in the way. (Read an interview by 48hills’ Emily Wilson with the artist here.) The collection by Iranian American artist Taravat Talepasand and others challenged the paradoxical nature of that hyphenate. That it coincided with the Women. Life. Freedom. movement is less coincidence than serendipity. Indeed, the slogan itself was here recreated in neon English and Kurdish. (Another striking neon piece, Sergio de la Torre’s “Undo Men,” wasn’t part of the exhibit, but it complements Talepasand’s work perfectly.)

From the solemn display of Badri Vilian’s “A Cup of Tea” (tea trays hung from a wall, as locks of women’s hair dangled from them) to Reze Zevvari and Romina Zabihian’s “Be the Voice of Iran” posters (vector art-style likenesses of Iranian women and girls who were murdered through “honor killings”), one might have thought this is your typical restrained, see-these-immigrants-the-way-Americans-rarely-do showcases—progressive enough to enlighten, but conservative enough to not shock. After all, one piece (“Persian Dance I-III”) was a cute old public access video of Iran-E-Man from Portland circa 1989.

Then one entered the proper gallery space upstairs, and all hints of subtlety flew out the window. This was where we found Talepasand’s “Blasphemy” series of porcelain figures (all of them women wearing hijabs with enormous breasts, each piece painted in various colors) and graphites (women wearing hijabs performing a striptease.) This is also where we found the shocking graphite piece “Death to the Bitches!,” in which a blade-wielding man held the severed heads of two women, their blood adding the only splash of color. The images outside the room only hinted at the brash violence and sexuality made plain in these works.

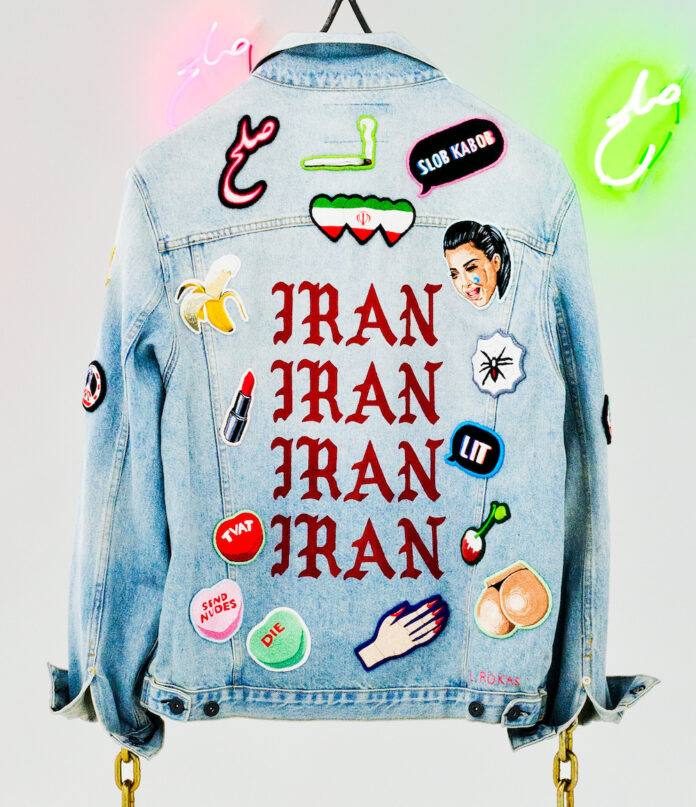

In the center of it all was “IRAN IRAN IRAN IRAN,” Talepasand’s 2017 piece that took a stylistic cue from the pre-MAGA Kanye West. Iranian-American contradictions tok the form of pop culture patches (created by Laura Rokus) on a denim jacket around a peace-sign metal hanger suspended by a noose. It hung over an Iranian-made rug (“Trump Runner”) on which the twice-impeached criminal’s face was repeated multiple times in the style of Kanye West’s crying ex-wife. (Neither mentions West, but he informs so much of them that one would be remiss not to mention him.)

Whereas Gobir’s works shows someone reclaiming the concept of “home” with relative ease, Talepasand’s collection reveled in the agony and ecstasy of her cultural tug-of-war. It could be tonally jarring, but it was always eye-catching.

It may not have been a day at the Smithsonian, but when the day was over, I was glad that the two women who left the strongest impression were the two featured in the exhibits rather than the two complaining about one of them.

HOLDING SPACE runs through August 20. Museum of the African Diaspora, SF. Tickets and more info here.