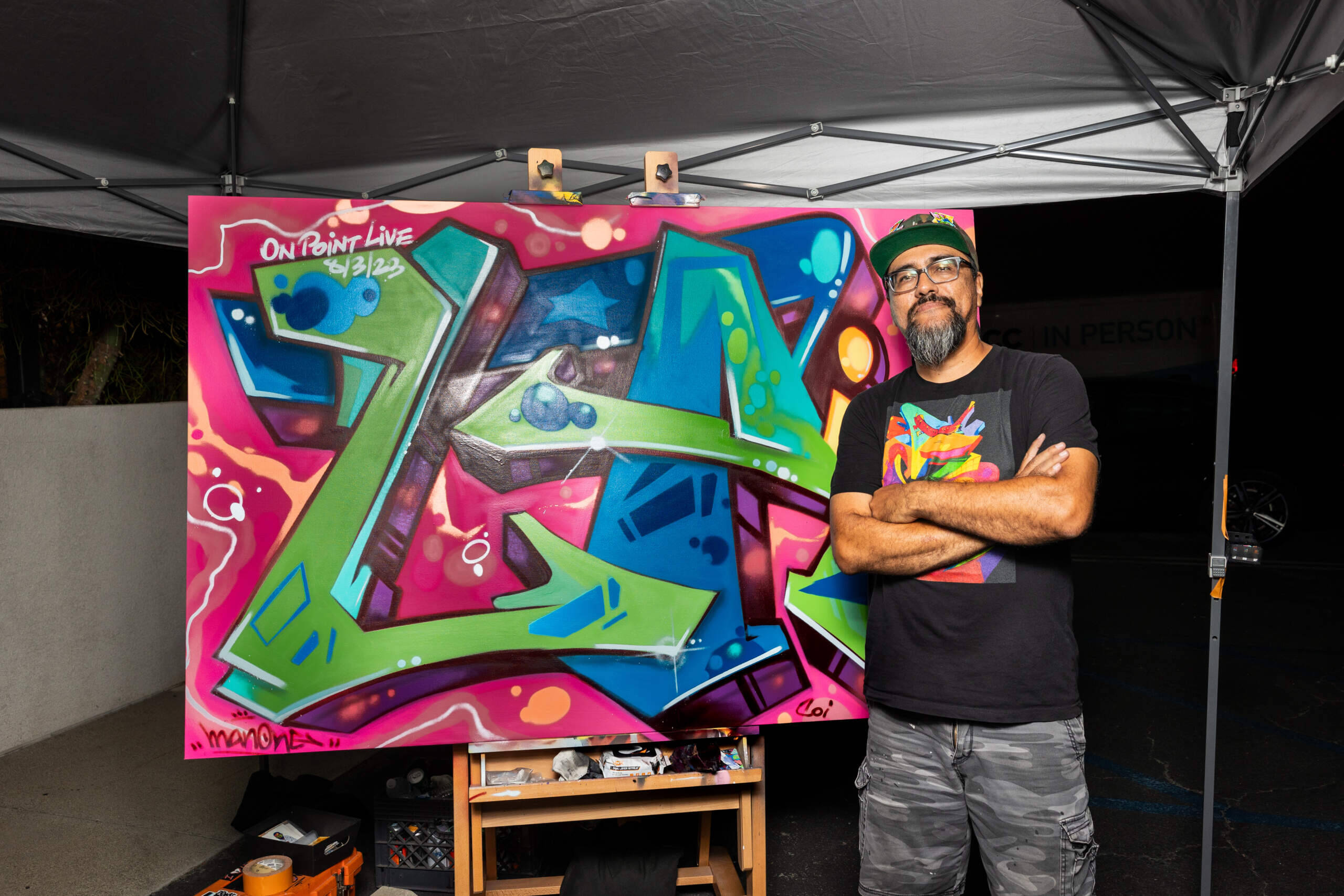

This conversation, in partnership with LAist, took place before a live audience at the Crawford, LAist’s live event venue in Pasadena, California.

The 50th anniversary of hip-hop.

Born in the Bronx, New York, hip-hop culture soon found some of its most talented, controversial, and politically influential rappers in Los Angeles.

Today, On Point: How West Coast hip-hop helped shape what’s become one of the most dominant cultural forces in the world.

Guests

Tyree Boyd-Pates, historian of Black culture. Associate curator at the Autry Museum of the American West.

Damita Jo Freeman, original Soul Train dancer and hip-hop pioneer. She helped popularize locking, one of hip-hop’s signature dance styles. Her new memoir is titled, “Are You that Girl from Soul Train?”

Transcript

Part I

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: On August 11, 1973, Cindy Campbell threw a back-to-school party. She asked her older brother, Clive, to provide the music. They set up in the rec room of a Bronx apartment block.

18-year-old Clive was better known as DJ Kool Herc. Herc stood behind a pair of turn tables and a mixer. He spun top hits from Aretha Franklin and James Brown, but he moved between records in a way that mixed one percussive break into another, removing the lyrics and chorus.

And, hip-hop was born.

Rapping, dancing and DJ’ing gave voice to a new generation of political consciousness in the Black community. It courted controversy and backlash. And now, hip-hop culture is so dominant in American culture, it’s hard to remember a time before the beat was king.

So today, on hip-hop’s 50th anniversary, we’re going to bring you a special conversation focusing on the influence of West Coast hip-hop.

Tyree Boyd-Pates is an historian of Black culture, and associate curator at the Autry Museum of the American West.

Damita Jo Freeman is a groundbreaking dancer, who began her career in 1973 on the legendary television show, Soul Train. She helped popularize locking, one of hip-hop’s signature dance styles.

We partnered with LAist, public radio for Southern California. And our conversation took place before an audience at the Crawford, LAist’s live event venue in Pasadena.

And I began by asking Tyree Boyd-Pates to define the most important aspects of hip-hop culture.

TYREE BOYD-PATES: So there’s five points of hip-hop. Locking is b-boying, MC’ing, DJ’ing, Graffiti. And then the last one, of course, KRS-One would kill me if I didn’t say this: is knowledge. And those five elements comprise of hip-hop culture. And the emphasis on knowledge is probably the most key. Because for Black youth, especially out of the ’70s and the ’80s, when they’re coming into their own, after the Civil Rights movement and the Black Power Movement, knowledge of self is the most critical aspect to why you b-boy. To why you rap, to why you DJ.

CHAKRABARTI: Yes. Okay.

BOYD-PATES: No, it’s deep, y’all. It’s deep.

CHAKRABARTI: No. And that’s exactly right. Someone asked me why a while ago, why I was so excited to do this event tonight, and my automatic first answer is that hip-hop is the American story. I would say it’s one of the most important American stories of the 20th century.

DAMITA JO FREEMAN: And it was this time when everything was changing. And dancing was changing, music was changing, like it all happened at once.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. This event is pegged to the 50th anniversary of hip-hop. The anniversary date is coming out in New York.

By the way, I think someone told me that there’s some folks, or maybe at least one kind of important person in this audience who’s really serious about New York hip-hop. He might also be the head of the LAist. (LAUGHS)

Now, I don’t wanna make a thing out of this, but East Coast, West Coast.

FREEMAN: Yes.

CHAKRABARTI: Which one is better?

FREEMAN: Uh-oh. We’re going to fight.

BOYD-PATES: (LAUGHS) We do a locking battle in the middle of the room.

FREEMAN: Yes. Some breaking, some locking.

CHAKRABARTI: But I keep raising the fact that popularly, we’re acknowledging East Coast. But, I was trying to think back about, how could we define the beginning of hip-hop in the West coast?

And one thing came up, Tyree, I want you to tell me what you think about this. This is from another historian who said the thing that helped give rise to hip-hop in the West were the Watts riots in 1965. Okay. Because in 1967, a man named Budd Schulberg founded a creative space titled the Watts Writers Workshop.

And that was supposed to help folks from the neighborhood have a place where they could express themselves. Yes. What do you think about that?

BOYD-PATES: That’s completely true. You have The Last Prophets who come out of Watts.

(AUDIENCE TALKING)

Hold it down for me. I love it over there.

Support me. Oh, and also it’s really beautiful because in hip-hop, the call and response, we’re a call and response culture. So if you love us or you like what we say and talk back to us, this is a part of the culture. Hello? Hello. That’s how you do it. That’s how you do it. Holler.

But call and response is really important. But The Last Prophets out of Watts. Yes. And we can’t forget that because there’s a group of people who have been historically suppressed. The best form of expression is creative expression. And so when you can’t use your hands, you use your mouth, and we can’t use your mouth, you use your body.

And that’s the beauty of hip-hop. And so you have to give credit to Parliament Funkadelic and what they made, because most of their records ended up getting sampled by Dr. Dre (LAUGHS) and all of the other MC’s and rappers because —

FREEMAN: That’s true.

BOYD-PATES: That’s who they grew up listening to. And so there’s revolution in who they’re sampling, and I think that’s what makes West Coast hip-hop so beautiful.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. So tell me more than both of you, how would you describe the things that distinguish West Coast hip-hop from East Coast? What do you think?

FREEMAN: To me, west coast hip-hopping in the beginning for me, I’m a locker, but to see the, how it changes into hip-hop and see, to me, hip-hop is really a name era. You, if you hear on tv, “They’ll say, oh, this is the Bandstand days. The ’60s were the rock and roll years, but now when they’re saying ’70s and on up, that was the hip-hop era.” It’s like an umbrella. And under the umbrella is locking. It’s popping. It’s breaking, it’s all of the style of dancing that the young people today are doing.

BOYD-PATES: Yeah. And what makes it West Coast? I got to give a shout out to the World Class Wreckin’ Cru. Cause that’s what Dr. Dre, of course, was a part of.

(AUDIENCE YELLS)

Thank you. You gotta give a shout out to Low Rider culture. That’s distinctly West coast hip-hop.

FREEMAN: Yes.

BOYD-PATES: Am I missing something? Tell me, what do y’all think?

What else makes something West Coast, if you don’t mind.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: G-funk!

BOYD-PATES: G-funk. G-funk. Yes. Egyptian Lover.

FREEMAN: Yes.

BOYD-PATES: Dickies. Dickies, Converse, Cortez. What else?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Hollywood.

BOYD-PATES: Hollywood.

FREEMAN: Hollywood.

BOYD-PATES: That’s right. And Central Avenue. Leimert. And hold on. And I would be remiss. And I would be remiss because what makes LA’s an epicenter for hip-hop has to be mentioned about Leimert Park featuring Project Blowed. Yes. And the Freestyle Fellowship and all of those great art.

(AUDIENCE MEMBER YELLS)

BOYD-PATES: Those are good things. Yes. Those are good things, that means we’re hitting the notes and Freestyle Fellowship emerged. And all of these rappers that came out from just miles down the street ended up changing the face of a genre.

That’s world renowned.

CHAKRABARTI: Oh, by the way, okay. I have to just tell you, it was telling me this earlier, so I hadn’t seen a ton of Soul Train growing up, but I was watching a bunch of videos of her dancing. And there was one that I just watched over and over again because A, you’re like a comet lighting up the stage and B, the man standing behind her is James Brown.

Okay? And get this, the godfather of soul, standing behind Damita Jo. And he’s looking at her, looking at her up and down. You can Google this, you’ll find it in a second. Looking at her up and down, and he looks like, he’s like, I do not know what to do. I’ll not be able to keep up with her.

FREEMAN: He didn’t, and I didn’t know what I was doing either because I never heard that song before.

This was the very first time that everybody, the world was going to hear Super Bad. And so when I went up on the stairs. When he, when we started, it was like, “Okay, keep going. He loves to play that beat. Okay, keep going.” So in my head, I’m looking, I’m smiling. I have no idea what’s coming outta his mouth. And when his mouth came, you could feel the music when it drops. So therefore I said, “oh, changed. I start dancing.” And I just kept going and his smile and I said, “oh Lord, I’m in trouble. I’m doing something. I don’t know what I’m doing.” But I just threw in the robot and I threw in so many different things.

CHAKRABARTI: It’s a work of art that you’re doing there.

I’m telling you it was. And here’s the power of it because it relates to what you were saying, even all these years later. Watching that little clip as a viewer you feel it. You still feel it. Yes. In your own bodies, that’s what you were able to do across decades. Yes. Now, I’m also wondering about the impact that the rise spread, the development of hip-hop, music, dance, and culture had on the very neighborhoods here that were giving birth to it.

FREEMAN: So it was, to me, hip-hop is a communication, dancing was communication. So therefore, by being accepted, also helped. That’s part of hip-hop, because young kids want to be accepted. Artists were paying attention to us. We are just kids off the street.

But now you are on a TV show, which there wasn’t any Black, there was American Bandstand, there’s four Black people on the show. Chocolate women, just moving. But no Soul Train was a group of people, young kids who wanted to actually shout out, “I’m alive. I can be a part of this world.” Hip-hop opened it up because it wasn’t just dance, it was everything.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah.

BOYD-PATES: Speaking about the regional elements of hip-hop, particularly the neighborhoods, you gotta give a shout out to Compton itself.

CHAKRABARTI: Totally.

FREEMAN: Yes.

BOYD-PATES: Shout out to Compton what Kendrick Lamar has been able to symbolize to Compton. As a Pulitzer Prize winning artist. Nobody in Compton ever thought they would bring a Pulitzer back to Compton. But that’s how important Compton is to this conversation. And I was listening to some interviews from Ice-T, and he was alluding to how. Gangsta rap out of the 1990s. So you think of The Chronic, you think Ice-T, you think N.W.A, what hip-hop was in the ’90s specifically for South Central was just journalism.

CHAKRABARTI: Yes.

BOYD-PATES: Yeah. And it was journalism, but it was taking the microphone and showing the world how much you were ignoring Black America. And if you ignore us, then we gonna show you some attitude. Straight Outta Compton was the new message for the 1990s. And the world hasn’t recovered since. And then don’t even get me started about Snoop Dogg and what he’s done for Long Beach. And he arguably is one of the people who’s put Long Beach on the map. He will tell you this.

(LAUGHS)

BOYD-PATES: And it was so attractive. It’s so attractive that Tupac Shakur himself was banging the West Coast more than people who actually were born here in the sense that Tupac was representing LA in particular, yeah. Because of the journalistic elements that the pioneers were making, too.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: Now, more of our special conversation on the influence of West Coast hip-hop that we’re offering you today on the 50th anniversary of hip-hop culture. My guests were historian Tyree Boyd-Pates and legendary dancer Damita Jo Freeman. We spoke before a packed audience at the Crawford, LAist’s live events venue in Pasadena, California.

Hip hop has become one of the most powerful American cultural exports that spread around the world. So I wanted to know more about how Tyree and Damita Jo would describe hip hop’s global impact. Here’s Tyree.

BOYD-PATES: When I think about hip hop’s impact on the world, I think about how you could literally put revolution in one person’s body and have them move so contagiously that the world wants to know how they did that.

FREEMAN: Yeah.

CHAKRABARTI: Yes.

BOYD-PATES: And to know that like hip hop started in the streets in the Bronx, but had impact. Okay, Bronx.

(LAUGHS)

From the Bronx, all the way to have an impact on Los Angeles and then spread like the best cold you could ever catch. (LAUGHS)

Clearly, I caught it.

No. But it’s something that reminds me as a historian that we are living in the history right now. To watch a Black musical genre take over the world is, it’s amazing. Makes my, gives me goosebumps.

CHAKRABARTI: Yes. So Damita just said about how seeing your kids, seeing your story on stage, hearing it in the music, how powerful that is and was picking up on that thought. Tyree, I just want to quickly hear from you. Tell me a little bit about how you experienced it and what it meant to you as a young boy.

BOYD-PATES: Yeah. Yeah. So I’m from LA born and raised. I feel like I’m the last person who can say that but shout out to the Angelenos who are listening and watching and stuff like that.

But I grew up as a Black kid in Koreatown. And being a Black kid in Koreatown in the ’90s, directly after the LA riots was definitely a time. And the beauty of it was that what was innovating in South Central, particularly when it comes to music, was spreading to K-Town. And I saw Black, brown and Asian people taking a hold of the genre and making it their own.

In Koreatown, you have all of these people, our Asian brothers and sisters who in K-town and surrounding areas, we’re able to innovate a genre, but also give homage to how Black and beautiful it was. I love that. And that’s what makes me. And so I touched a turntable in Griffith Park at a barbecue, and it was DJ Quik.

Who like showed me the turntable, but my uncle used to play Tribe Called Quest over and over again in our bedroom where we lived together. And that has stuck in my DNA ever since. And she hasn’t broken up with me yet.

(LAUGHS)

Neither have I her.

CHAKRABARTI: It’s easy to look at the 50 year mark, to look back on things with kind of rose-colored glasses.

BOYD-PATES: Hello. Hello.

CHAKRABARTI: But because when you’re talking about Straight Outta Compton, it changed everything. But there was backlash, huge backlash. So I want you guys to talk about that for a little bit, because we’re celebrating hip hop, but we also have to be mindful.

FREEMAN: Yes.

CHAKRABARTI: That it’s been a journey. It’s been a fight. It’s been still pushing against the same forces. That wanted to ignore your stories to begin with.

FREEMAN: That’s right. Yes. I’m listening to when you are saying, pushing. The word pushing in my head. That’s what we did. So in the beginning, hip hop was a slow process. First, we had to be acknowledged.

We just wanted to be heard. So therefore, hip hop, to me, it grew into a positive for everybody. Because now everybody has that opportunity to strive, and it’s going to be hard all the way. It was always hard, because it took people who have visions that they could do it, and then there are people who have visions, “No, they can’t.”

And want to keep us down. But we kept striving and we lived off the music. Of all these artists. Now when they came out of the jail, saying their whole thing, nobody paid attention to them. And so they now are something special, too. The word hip hop to me always thought, hip hop is like a bunny. Nice thing. Because, street dance, they didn’t really want to say street dance. It sounds hard, it sounds Black.

Let’s find another word. And a group to me saying:

“Hip-hop, the hippie, the hippie

To the hip, hip-hop and you don’t stop the rockin’

To the bang-bang boogie, say up jump the boogie”

So it was cute. Always striving to make, instead of whatever color you are, your genre or the words that they put out has to be likable in order to be acceptable.

CHAKRABARTI: But this is a thing that I think the gift that West Coast Hip Hop gave the world.

I completely agree with you and see what you’re saying. And then we have groups coming out of the West coast who are like, “I don’t care if you like me.”

FREEMAN: That’s right. That’s right.

Because it evolves.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah, exactly.

FREEMAN: Hiphop evolves. It gives us the right to say, “I don’t care.”

CHAKRABARTI: That’s right.

BOYD-PATES: And that rebellious spirit leads me to say that it was initially a counterculture, like even LL Cool J will tell you this, back in the day, no one ever actually thought hip hop was gonna go this far, like it wasn’t expected to catch on.

And the early adopters of hip hop, we’re okay with that. Because it wasn’t mainstream. But as I think about the developments and the ways in which West Coast hiphop has made a name for itself, especially in the ’90s, I’d be remiss to not include how important women were into this conversation.

Yes. J.J. Fad and Supersonic, Lady Rage. Yo-Yo. Whether hip hop wants to give credit to women, Black women, especially, exclusively, it’s on the shoulders and backs of black women, who were the first dancers of all the beats and actually gave the men the validation that their songs actually could catch on.

FREEMAN: That’s right.

BOYD-PATES: On both coasts, by the way.

CHAKRABARTI: Did you also say that Black women were making hip hop that you say was more inspiring thematically?

BOYD-PATES: I’m a historian, so I look at cycles. So it’s not surprising to me that Black women rappers are dominating the genre currently.

Because there was a period of time when Queen Latifah had a few people running for the hills.

(AUDIENCE TALKING)

CHAKRABARTI: (LAUGHS)

FREEMAN: She did.

BOYD-PATES: And my man agrees with me. I look at the cycles. And whether it’s the Meg thee Stallions, and then the names of this era, who are taking and using their agency to show that their lyrics are more than what they look on the paper.

Like I love it. Yeah, I love it. And that’s what I’ll say on that.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. Yes. I promise you I’m seeing the questions come in, and I’m gonna get to them ’cause they’re good. But I’m gonna follow this thread just a little bit longer. ‘Cause I think it’s important because sitting on the stage, we’re in your shadow, Damita Jo, is a Black woman who is integral to the development of hip hop. Can you just describe a little bit about what that was like being a woman, and even what was then, as you said earlier, a pretty male dominated —

FREEMAN: Yes, it was. At that particular time when I was dancing, yes, men were on the floor dancing their heart off, and yet women are noted to make our husbands or our loved ones, we are beside them.

We make them stand out. But this was a time where, for me, I wanted a woman like me and my mother and my family, because they were educators and they were teachers, and they always believed, and they instilled in me that you can be somebody.

All you have to do is just stand up and be it. And so therefore, when I watched the guys and I watched the ladies, how they stood back and let the guys take the floor, then I just went, “No, that’s not right. Women should be in there.” And then if you even look into the 1990s, there are girls on the poles.

They are, “Hey, yay. Look at my body.” So I’m just saying that hip hop to women, it’s a growing thing. But now we’re at a point, we have Queen Latifah. We have all these young people who are taking the rims and rapping. So they’re not just letting the guys do their little thing. They are stepping up.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. I wanna talk a little bit more about women and also the treatment of women in hiphop culture, right?

FREEMAN: Yes.

CHAKRABARTI: ’cause I do think we have to talk about that a little bit more. Yes, absolutely. Rolling Stone right now is putting out this series of top 100 tracks in hiphop for different styles of hiphop. What they put is number one was Nuthin’ But A ‘G’ Thang. Okay. According to the Rolling Stone editors, they say, “It changed everything.”

This is what they wrote. They said, “It made it the default style for Los Angeles past and present. It brought street culture to the forefront permanently and forced every hip hop artist to decide whether they were gangsters or not. And it made Dr. Dre the undisputed king of West coast hip hop for generations to come.”

Okay, so then they say, “The song also evokes some troubling responses.” For folks who’ve seen the video, there’s some pretty difficult scenes regarding male treatment of women. And also some of the actual lyrics in the song. That wasn’t the only one, in the ’90s, obviously it stands out because it was such a massive and important song.

So that’s also part of hip hop’s history and legacy. And I wonder how you think through that.

FREEMAN: Definitely for me as a woman, I don’t like that.

(LAUGHS)

FREEMAN: Yeah. I don’t like to be called the B word a lot. Maybe it’s because of my background. Maybe I was around so many strong women. I just can’t see another woman tell another woman that you’re B, and then use it in a record or in a way to try to make it comfortable. But I don’t like the B word. I don’t like the F word. I don’t like all these words. Because you could still insult somebody or love somebody with other words, but they don’t choose to do that because we are now, to me, at a time, we’ve got to shock everybody.

BOYD-PATES: (SIGHS)

(GUESTS LAUGH)

BOYD-PATES: Misogyny is as American as apple pie. We all know this. Hip hop is a reflection of American society. And given that misogyny is as American as apple pie, misogynoir is as important or significant in the Black community. And during the ’90s, Nuthin’ But A ‘G’ Thang was the song.

It was the song. And Too $hort has a catchphrase. Of which is his favorite word is a B word. Oh, thank you. Thank you. And as a historian, again, I look at the ebbs and flows of how misogyny has been interwoven within hip hop. But also how it’s, how women, Black women, particularly who are rappers, have undermined certain tropes, right?

Yeah. Of the Jezebel trope and all of these caricatures of Black womanhood, and then have reclaimed it on their own terms. And again I love Queen Latifah, especially the golden age of hip hop, because who you calling up? U N I T Y. Yes. And one we would be remiss to not look at that as a response to her contemporaries.

Who were calling Black women beasts. But now the City Girls are up. And they’re calling each other the B word in an endearing way. And I’m no one to tell women what to say to one another. But I am responsible to tell men what they shouldn’t tell women that they should be called.

And I think as communities become more educated about the impacts of words, especially to the LGBTQI community, when it comes to hip hop that education has to happen. And if we’re being honest on this panel we’re seeing four of the five elements of hip hop dominating the genre, but what we’re missing? The knowledge.

CHAKRABARTI: The knowledge. Yeah, knowledge.

FREEMAN: That’s true. That’s true. Knowledge is a key.

CHAKRABARTI: I told this to you, we’re gonna need hours just to get started actually. So let me do justice in honor to some of the audience. Questions here, Tyree, this one’s for you.

Because you’re talking about revolution, right? Someone’s asking, “How does white flight and the New York City financial crisis of the 1970s come into the American story? Because the question is abandonment by capital and whiteness necessary for revolution?”

BOYD-PATES: What?

(AUDIENCE LAUGHS)

CHAKRABARTI: It’s the LAist audience, man, I’m telling you.

BOYD-PATES: Sheesh. Sheesh.

FREEMAN: (LAUGHS)

CHAKRABARTI: I thought I’d threw you a softball. That was a softball?

BOYD-PATES: Oh, okay. So can you repeat that? Repeat, paraphrase it just so I can answer it. Forthrightly. Cause that was like a dissertation.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. I think the point of that question is asking, revolution comes by for certain reasons.

BOYD-PATES: Sure, sure.

CHAKRABARTI: And one of them is just the abandonment of community.

BOYD-PATES: Of course. Yeah. Yeah. So from a historical perspective you have to look at New York, you can look at LA. For the sake of this conversation, we’re gonna focus on LA. The ways in which freeways have cut LA into certain quadrants.

Yeah. Particularly like the Sugar Hill area, the West Adams district, for those who don’t know, it’s Sugar Hill. Is a freeway that has cut a Black neighborhood in half. But there’s also been freeways that have been built to make sure that the Black community doesn’t leave South Central. And come above the 10. Hello. Not an accident. And you think about, so the suburban elements of LA, and you think about why Crenshaw or Compton. Compton especially used to be an all-white town. Where are all the white people now? Yes. And why is Compton seen as the most dangerous area in one of the most dangerous areas of the city?

White flight. And when white flight occurs, so does divestment happen, as well. And when divestment happens, so does hyper policing. And with hyper policing comes police brutality. And that divestment creates the music, the journalistic elements that we’ve been listening to for the last 20, 30 years.

But to be honest, as a child of the hip hop generation, the hip hop generation will tell you, we don’t need you to divest from our communities to hear our voices.

CHAKRABARTI: That’s right.

BOYD-PATES: But America’s issue, Los Angeles’s issue, Harlem’s issue is now pressing because gentrification is happening. So what happens?

The children of those whose parents fled, through whiteness out of inner cities, and now their children are the new adopters of the genre. And they love Black culture as much as Black people love Black culture. Now there has to be a new conversation about homage and appropriation.

But hopefully if investment occurs while that conversation is happening, then we can give back to the knowledge base that started the genre to begin with.