In 2014, thousands of Yazidi women and children were enslaved by the Islamic State (IS) group in Iraq and Syria. Their fellow Yazidis launched a rescue effort almost immediately, but nearly a decade later, their task is still unfinished.

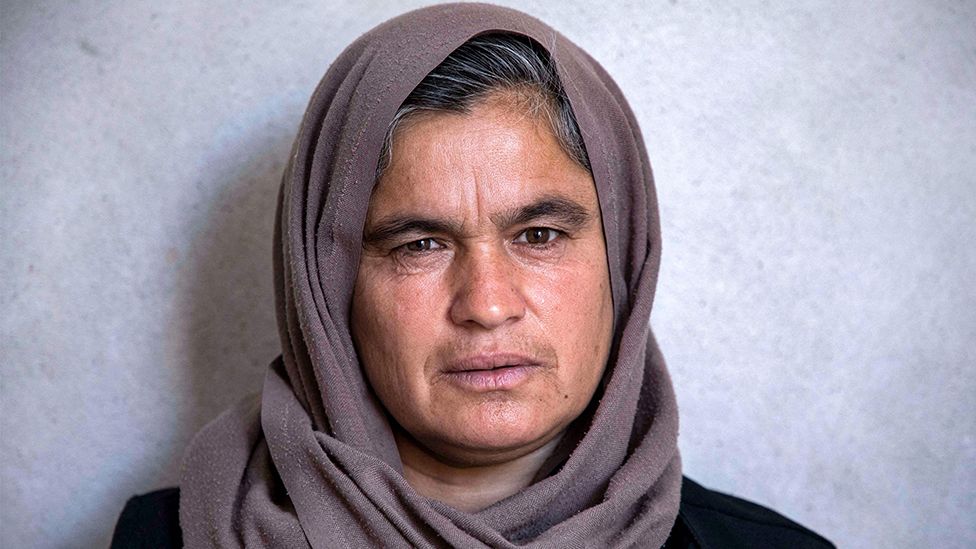

In November 2015, Bahar and her three young children had just been sold for the fifth time.

She had been one of many Yazidi women taken prisoner by IS, who had swept into her village in the Sinjar district of northern Iraq 18 months earlier. A religious minority living in Iraq for nearly 6,000 years, the Yazidis were considered infidels by the IS fighters.

Her husband and eldest son had been taken away. She believes they were shot and buried in a mass grave.

Bahar remembers how she and her three other children were all lined up in a room, crying because they thought they would be beheaded. But instead, they were being sold.

That’s when the horror really began.

Bahar says she had to serve the IS fighters whose property she became. “I had to act like their wives, when they wanted. They would beat me if they wanted to.” Her children, all under the age of 10, were also beaten. One of her daughters was smashed in the face with a rifle butt.

Her fourth “owner” was a Tunisian called Abu Khattab. “We stayed at his home, but he would also loan me out to work as a cleaner at two other IS bases. At all these places, I would go to work, I would clean and I would be raped.

“And there were air raids all the time. IS fighters would be running around, getting weapons, or hiding from the bombing. It was chaos, it was worse than a nightmare.”

One day, when Bahar and her children were in Abu Khattab’s house, a white car with blacked-out windows pulled up. The driver was dressed in black with a long beard, and looked no different from many other IS fighters.

Bahar realised she and her children were being sold once more. Overwhelmed with the situation, Bahar screamed at the man to just kill her – she couldn’t bear any more.

But what happened next changed everything.

As they drove off, the driver said, “I am taking you somewhere else.” Bahar didn’t know what was happening or trust the man, and she began to get frantic. He stopped the car, and called someone on his phone. He then handed the phone to Bahar. It was the voice of Abu Shuja, a man known to have arranged the rescue of many women and children. Now she realised that the driver had bought her so she and her children could also be rescued.

Bahar was driven to a construction site somewhere near Raqqa, in Syria. She was dropped off and told that a man would come, and say the code word “Sayeed”. She should go with him.

Sure enough, someone arrived on a motorbike, and uttered the word. He told Bahar and her three children to get on his motorbike, and said, “Listen, we are in IS territory, there are checkpoints. If they ask you anything, don’t say a word, so they don’t recognise your Yazidi accent.”

What’s happened to Iraq’s Yazidis?

Since the defeat of IS in 2017, the traumatized Yazidi community has tried to recover. And yet, as Rachel Wright reports, more than 100,000 Yazidis remain stuck in camps, unable to return to their homes.

Listen to Assignment: What’s happened to Iraq’s Yazidis on BBC World Service at 02:32 GMT (03:32 BST) on Thursday 6 July, or online at BBC Sounds

Bahar says that the man took them to his home: “They were so nice to us there – we showered, they gave us food and painkillers and they said, ‘You are in safe hands now’.”

Another man took pictures of Bahar and her children and sent them to Abu Shuja to prove that he had the right people. Then at about 03:00 the next morning, the family was woken up and told to get ready to move again. The man whose house they were staying in gave Bahar his mother’s ID card and said that if anyone should stop and ask, she should say she was taking her son to visit the doctor. “We drove through lots of IS checkpoints but no-one stopped us.”

Finally they got to a village on the Syrian/Iraqi border and Bahar was met by Abu Shuja and her brother. “I was on the verge of collapse,” she says. “I don’t remember much else that happened after that.”

More than 6,400 Yazidi women and children are thought to have been sold into slavery after IS captured Sinjar. Another 5,000 Yazidis were murdered in what a UN commission termed a genocide.

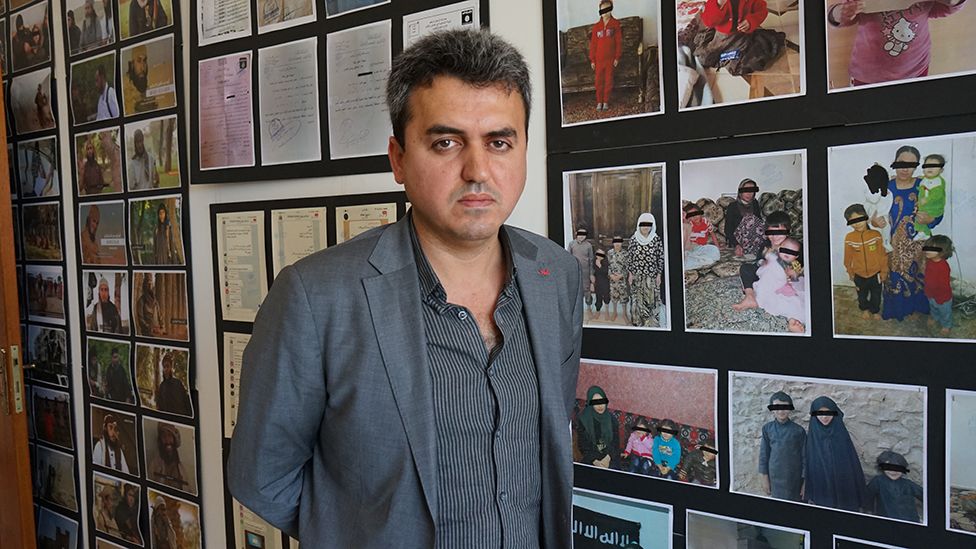

Abu Shuja, who arranged Bahar’s rescue, wasn’t the only one to be concerned about the women and children kidnapped by IS. Businessman Bahzad Fahran, who lived outside of IS-controlled areas had set up a group called Kinyat – to rescue Yazidi women and children and record the crimes of IS fighters.

Kinyat got word that IS fighters were buying and selling kidnapped Yazidi women and children online, particularly on Telegram. “We would infiltrate these online groups under borrowed names or using IS fighters’ names,” says Bahzad.

On the wall of his office in the Kurdish area of Iraq, he points to printed-out screenshots of the Telegram chats that he saw. One of them is in English, advertising a girl for sale: “12 yrs old not virgin very beautiful”. She cost $13,000 (£10,000) and was in Raqqa in Syria. Then he shows me a picture of the girl posing in a suggestive way on a leather sofa.

Bahzad says that these Telegram chats would give details of where the kidnapped Yazidis were located: “We would get in touch with people living around there and ask them to look for this kid.”

It was easier to find young boys because they were allowed out of the house more: “We’d also get the [kidnapped person’s] family to send information so when we confronted the boy, we could give them evidence that we were genuine,” says Bahzad.

“When we were rescuing families, like women with their children, we had to have a series of codes, or signals to let them know we were there to rescue them, and to let us know when they are alone.”

The process differed in every case, but each one involved money, and fake documents to get through IS group checkpoints.

It was too risky for Yazidis to enter IS areas, so the act of rescue had to be carried out by local smugglers, who were more used to shifting cigarettes and forbidden alcohol.

“These guys did it all for cash,” says Bahzad. “That was their only motive. Many people were paid thousands of dollars to buy back these girls.”

Kinyat says that 6,417 Yazidis were taken captive, but 3,568 either escaped or were rescued. Bahzad himself rescued 55 people but according to the UN-backed International Organization for Migration (IOM), about 2,700 Yazidi women and children are still missing. Many of them could still be with their kidnappers.

Bahzad says that it has become more and more complicated to trace victims. After IS was defeated, the fighters and their families fled to other areas. Some are in Turkey, Iraq, Syria and some even went to Europe.

Bahzad says there are Yazidi children who were five or six when they were abducted and who have completely forgotten their language or who they are: “They don’t know anything about being Yazidi. And they even forgot their families.”

The wider future for the Yazidi people also remains uncertain.

“The Yazidis have been under attack for many centuries, and a lot of the Muslim population, younger or older, still believe they should convert or die,” says Haider Elias, the head of the largest Yazidi advocacy organisation, Yazda. “And that’s why we believe IS is not the extent of it, or the end of it, and that’s a big fear for the Yazidis.”

Of the 300,000 Yazidis who fled their homes in Sinjar from IS, almost half are – like Bahar – still living in tented camps in the Kurdish region of Iraq. They can’t go back to their homes in Sinjar district because it has been almost completely destroyed, and its strategic position on the Iraqi/Syria border makes it dangerous territory – with militias who came to fight IS now fighting each other for supremacy.

Elias says the community is frightened that it will be the subject of another massacre at any time, and that many Yazidis are now migrating. “A sense of security is really important for them. It’s a big thing. They don’t feel secure.”

It cost about £16,000 ($20,000) to buy Bahar’s freedom. She’s 40 years old now, but looks older than her age – beneath her headscarf her hair is now mostly grey.

She has lived in a camp for eight years since her rescue. Sitting on a thin mattress on the floor of her tent, she takes out a plastic folder with pictures of her missing family members.

Not knowing what happened to her husband and eldest son, and dealing with the trauma of being repeatedly raped, has made Bahar very ill – both physically and emotionally.

Her other children are still with her, but she says they are still in shock, and anxious all the time. “My daughter has injuries from the beatings she endured,” she says. “I have to keep fighting and keep going. But at the moment, the way we are right now, it’s like being the living dead.”