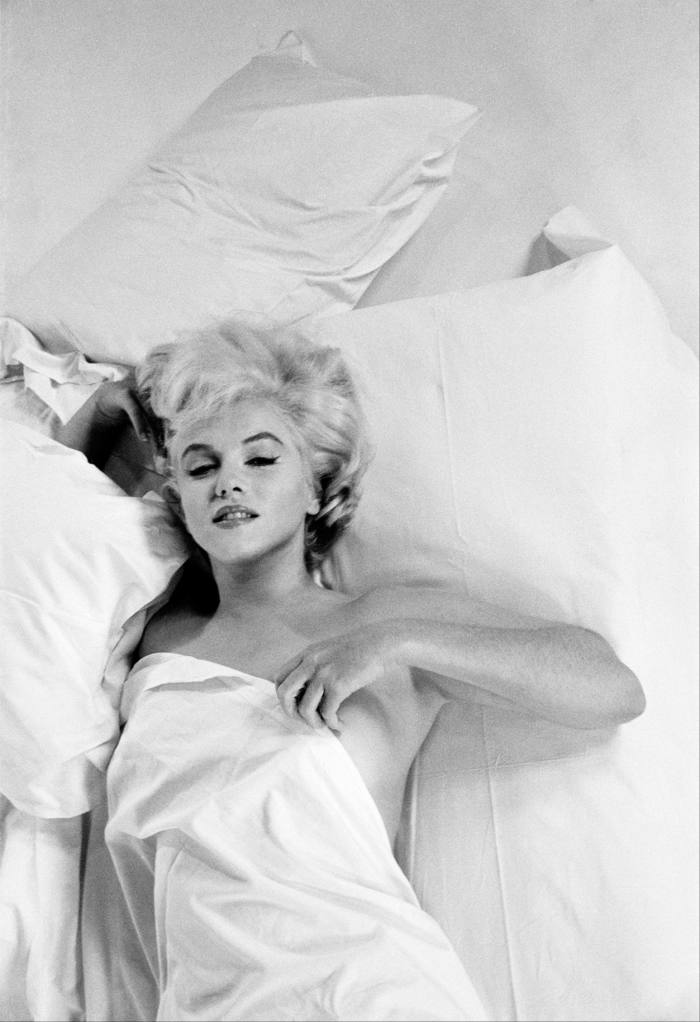

“As a photographer, one has to accept the fact that one does invade other people’s privacy,” Eve Arnold commented in a BBC documentary in the 1980s.

She was expressing misgivings about her professional relationship with Marilyn Monroe, and her intimate portraits of the actress that would establish Arnold as one of the 20th century’s leading photojournalists. But Arnold, who died in 2012, could equally have been talking about another, little-known project: her year-long study of backstage scenes at community fashion shows in Harlem, shot in black and white at the start of her career in the early 1950s. A selection of those images are on show in West Sussex as part of “To Know About Women: The Photography of Eve Arnold”, a retrospective that opened this month at Newlands House Gallery in Petworth.

“This was a time when the mainstream fashion industry was entirely white, and black women were not considered to be clients,” says Maya Binkin, the gallery’s artistic director, who curated the exhibition. “The models Arnold photographed made the clothes themselves and put on shows in hired venues for paying black audiences. It was a whole developed, professional scene. And Arnold was everywhere: present, but invisible.”

The Harlem series was Arnold’s first assignment. What she produced was a nuanced study of style, elegance and self-reliance, captured just before the US civil rights movement.

The photographs of models, often mid-change, and the crews of agents, dressers, make-up artists and security guards that surrounded them, exude energy and action. In the early 1950s, Arnold’s reportage approach to fashion photography (Binkin describes it as “slow journalism”) was unusual, an antecedent to ubiquitous shots of 1990s supermodels backstage. But it was nothing like the contemporaneous static, posed editorial images of white models shot in studios by Arnold’s 1950s contemporaries, such as Nina Leen or Richard Avedon.

At times, Arnold’s Harlem photographs feel intimate to the point of unsettling — that invasion of privacy she acknowledged.

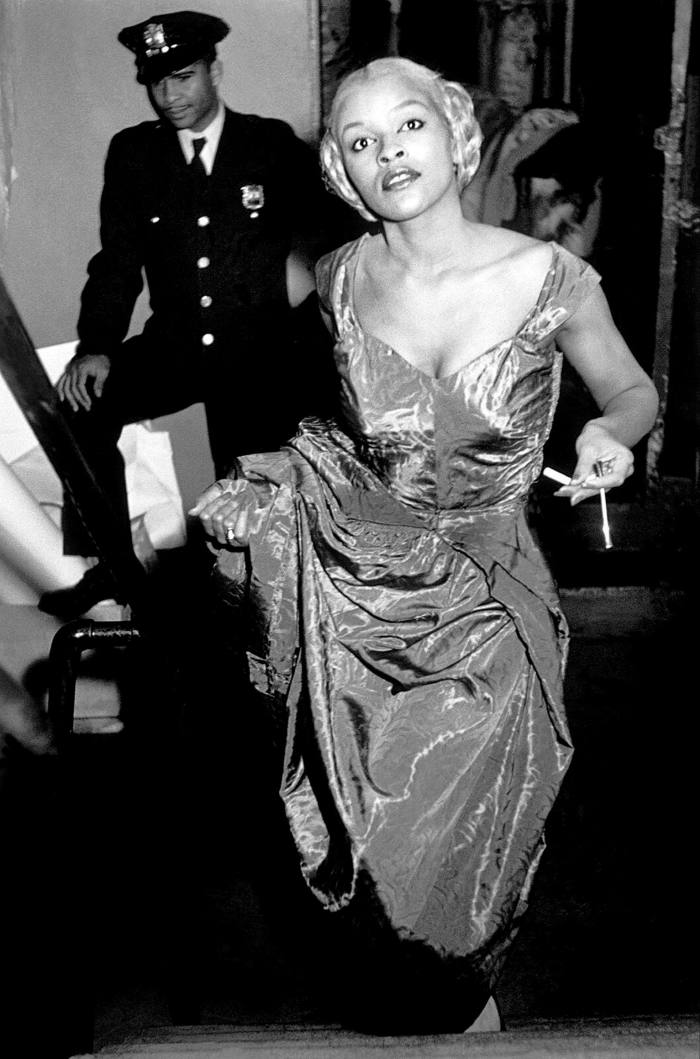

Arnold’s star is Charlotte Stribling, a young model known as “Fabulous” and recognisable by her hair, dyed a silken blonde and coiled in plaits around her ears. In one shot, Stribling bends to step out of her underwear with her back to the camera. It is a moment of inhibition and hurried action — the model is changing costumes — but there is little vulnerability in her nakedness. She could be mooning at us, not least because she and her dresser are laughing.

Arnold would later note that Stribling changed her walk when she first met her, the moment when the novice photographer realised her camera was always intrusive

In another shot, a luminous Stribling waits backstage for her cue at the same fashion show, held in the Abyssinian Baptist church on West 138th Street in 1950. Arnold catches Stribling as she emerges from the shadows wearing a lavish evening gown, her hair framing her expectant face like a nimbus, while a security guard hovers behind her.

Binkin says Arnold achieved the effect without artificial lighting. “It would be a case of going back to the dark room and praying that something was going to come out,” she says. “But she turns the dark church to her advantage.”

Arnold was born in Philadelphia in 1912 into a poor, working-class Jewish family. She shot the Harlem series as a student on a short course at the New School for Social Research in New York, led by Alexey Brodovitch, the legendary art director of Harper’s Bazaar (Brodovitch had also taught Avedon and Irving Penn).

She was in her late 30s when she joined Brodovitch’s course, at a moment when her marriage was failing and she had left her job working in a film processing factory in search of intellectual stimulation.

Brodovitch assigned her the subject of “fashion”. She had heard about the 300 shows that took place every year in Harlem, and contacted the modelling agencies who organised them to ask if she could document them. Perhaps her maturity worked in her favour, allowing her Harlem subjects to relax in her presence — Arnold was 20 years older than many of the models.

Like Arnold, we become present but invisible in their world. The photographer was a reticent figure, at 4’10” an unobtrusive presence more interested in her subjects than commanding attention herself, says Binkin.

Arnold sent her Harlem images to US fashion magazines in the hope of publication, but none — including Harper’s Bazaar — would publish them, a refusal that Binkin attributes to racism. Arnold did find a UK taker, Picture Post, which ran the series over an eight-page spread, though Arnold was unhappy with the accompanying text, which she felt misrepresented the shows.

Regardless, the Harlem series caused a sensation with readers and eventually led to an invitation for Arnold to join Magnum Photos, the prestigious photographer’s agency — with Inge Morath one of its first two female members. The membership would lead to a 60-year international career, including as a Sunday Times photographer from the early 1960s to the 1980s.

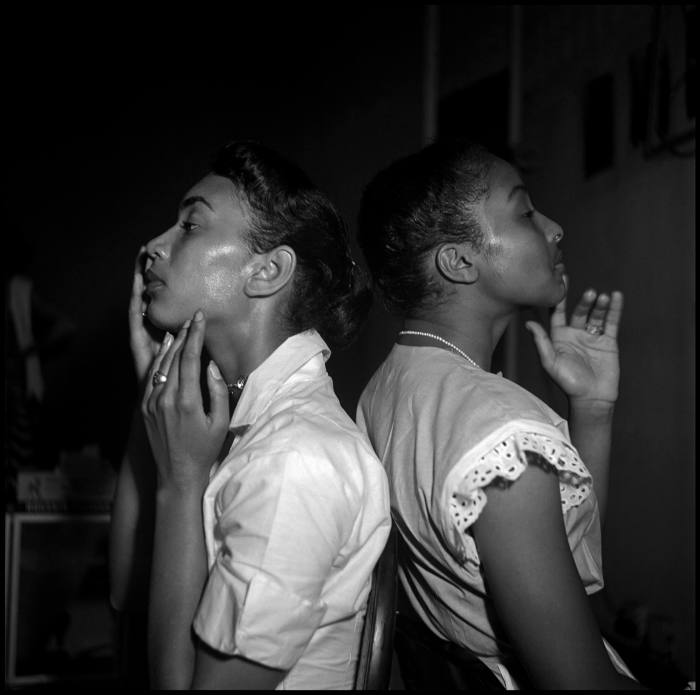

Arnold’s Harlem shots are discomfiting in many ways. Some show models applying skin-bleaching creams and straightening their hair, common practice at the time, but in contrast to another sequence of Arnold portraits — “Black is Beautiful” — also on show at Newlands, shot nearly 20 years later in 1968.

Here are two subjects belonging to a new generation of black women formed in the civil rights era, who promoted pride in black features: Arlene Hawkins, model and owner of Arlene Hawkins Cosmetics, a beauty brand for black skin and hair, and Cicely Tyson, an actress whose face appeared on the cover of Miles Davis’s 1967 album Sorcerer and later became his wife. Tyson and Hawkins are presented with natural hair.

The Harlem fashion shows have continued in various forms since Arnold shot them. By the 1970s, the scene had produced The Harlem Institute of Fashion and the Black Fashion Museum, although both organisations closed in the early 2000s. More recently, Harlem’s Fashion Row agency, which represents black designers and brands, opened New York Fashion Week in September 2022.

Binkin and Nicola Jones, director of Newlands, made efforts to track down the people involved in the early 1950s shows shot by Arnold, including Stribling and the other models, without success. “They would be in their 90s now,” says Jones. Hawkins, too, they were unable to trace; Tyson died in 2021. “Someone told me Fabulous’s agent became good friends with Eve, stayed in touch and came to her funeral,” says Binkin, although she discovered he has since died.

Their main sources for the story have been Arnold’s own documents, including her memoirs, and the recollections of her son, Frank.

Over the course of her career, Arnold would alternate between shooting portraits of famous people, most famously Monroe, and the photojournalism that echoed that first assignment. She returned to record black American society again and again, often when few mainstream magazines were interested.

In the early 1960s, she went on to document for 18 months the Nation of Islam movement of black supremacy, championed by Malcolm X, for a series eventually published in Esquire. Later assignments for the Sunday Times included recording people — often women — at work in China, Afghanistan, Russia and South Africa.

The Harlem series recorded a significant moment in African-American fashion that would likely have been undocumented without her.

“Maybe her reportage style of fashion photography would have happened anyway, it was the obvious next step,” says Binkin. “But she did it first. Her camera turned ordinary people into something special.”

‘To Know About Women: The Photography of Eve Arnold’ is at Newlands House Gallery until January 7 2024

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @financialtimesfashion on Instagram