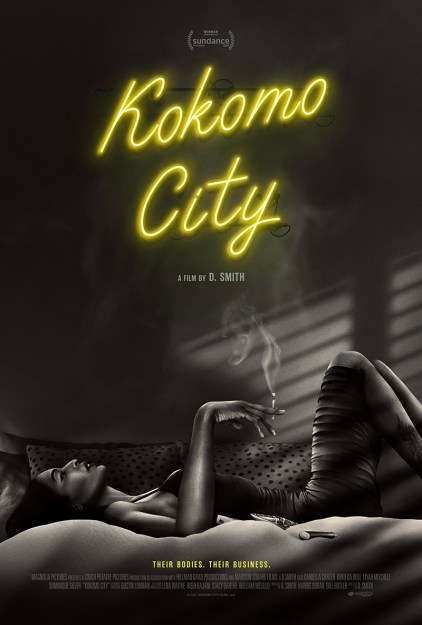

“My approach to doing Kokomo City in general was to just create a film that I would want to watch,” D. Smith says during the first of two conversations to discuss her 2023 Sundance and Berlin Film Festival Award-winning documentary.

An up-close look at the lives of four Black trans women sex workers in Atlanta and New York City — Daniella, Liyah, Dominique, and Koko da Doll — the film, opening this month in theaters nationwide, was shot in beautiful black-and-white and moves to an infectious beat.

Far from being trauma porn probing tragic downfalls, Smith’s debut feature has swagger, daring to be entertaining while affirming the power and experiences of these women.

“As selfish as it is, that was truly my approach,” says the writer-director. “Would I want to watch this? How would I want this to look, and what will keep my attention? What are some of the things that will keep my attention that are real and true to transgenderism and also to Black trans women?”

Smith says her supportive cast felt the same way, adding, “It’s very hard to paint the picture of who we are when we’re surrounded by fortresses. It actually dehumanizes us, as much as we have a lot of allies that are trying to protect us. But we have a lot of rules and words that you can’t say, and questions you can’t ask. It’s very segregating, actually. So I wanted to do something that a lot of people would be drawn to.”

A two-time Grammy-nominated songwriter-producer — who actually never brought up that tidbit while recounting her earlier success in the music biz — Smith has experience drawing audiences and artists to her vision.

With impressive credits, like co-writing, producing, and providing the featured vocal on Lil Wayne’s epic “Shoot Me Down,” and writing and producing Billy Porter’s No. 1 Billboard Dance single “Love Yourself,” Smith clearly brought a hit-maker’s eye and ear to crafting Kokomo City. She also provides some original songs for the film’s soundtrack.

The women in the film provide their strength, humor, vitality, and, particularly in the case of Daniella Carter, who also appeared in Elegance Bratton’s 2019 documentary Pier Kids, their wisdom.

Interviewed in their homes, or going about their lives, or getting their bills dancing at Hush Night — a private party for Atlanta’s “most beautiful vixens” and the men who love them, hosted by promoter Lenox Love — the film’s cast are its treasure. So it was indeed tragic that one who shines in the film, Koko da Doll, a.k.a. Rasheeda Williams was fatally shot on April 18 in Atlanta.

Her death adds to the dreadful crisis of trans and queer individuals killed violently throughout the U.S. Her life, as expressed in her presence and in her own words on-camera, may yet convey meaning to those who struggle to understand women like Koko.

Audiences will still get to know her in this film. Fortunately, she had a chance to see it, along with the rest of the cast and crew at the film’s world premiere at Sundance last January.

“Koko got the full experience,” recalls Smith. “She got the red carpet. She got on the stage. She got to see herself. And she was so humble. It just meant the world to her. It meant the absolute world to her. She was so grateful. It was almost unbelievable how soft-spoken she was in person outside of the film, and so sensitive and just beautiful.”

METRO WEEKLY: Let’s start at the beginning, making the movie. I read an interview that you did, so I know that you started in music. What led you from music to filmmaking?

SMITH: It was complete divine intervention because I was in such a low place in my life struggling to maintain a lifestyle or supporting myself musically when the industry really didn’t see it for me as a trans woman. And I think that because it was so new and it hadn’t been done, especially in Black music. And people didn’t know how to react to that, other than, “Oof, cut it off.”

So all the phone calls and everything stopped, and I ended up being homeless, sleeping on couches for years due to lack of experience with any other work ability and also pride. It stifled me, and it kept me stuck for a very long time. So I was forced to create another opportunity for myself. The gift of Kokomo City was brought to me, and it made so much sense.

To go further, I reached out to directors to help — well, to direct — because I wasn’t a director, and just got turned down by everyone. It was just such a clear sign from the creator that this is for you. Like, “Hello, stupid. Wake up. I can’t make this more clear that this is supposed to be for you.” And it just all made sense.

MW: A lot of people might have seen it the other way, as in, “Oh, well, this is saying that I’m not meant to do this.” But you felt propelled?

SMITH: Oh, yeah. And inspired. I mean, I’m one of those crazy creatives who just loves challenges, I do. I prefer to have a safe place to live while I’m being challenged, but it taught me so much. It taught me that I needed to be humble. It taught me that I needed to listen. It taught me that I needed to be open, all those things I thought I had together. And so the whole process, even talking to the girls, I learned so much from them. Even my approach to them was maybe a bit judgy. Not that they were beneath me, but I went in there with preconceived ideas. The whole process was very healing.

MW: It doesn’t come across in the movie, by the way, that there was any judgment coming from your side of the camera.

SMITH: It went away so quickly. After meeting the girls, even before I started to film, just talking with them in person, I’m covered with chills. I was fortunate to have the opportunity where I wasn’t kicked out of the house that early. Eventually, I was, because I was just a hard-headed-ass bitch. I didn’t want to listen to nobody. But I wasn’t a child and I didn’t have to do sex work. And that’s not the story for a lot of trans women. So I was just humbled by their strength and their determination and the things that they go through. And my situation really felt very minute compared to what they have to do on a daily basis.

MW: I have to ask about the fact that you directed and edited the film, and there is some of your music in there. I really like the closing credits song, “Children of the Rainbow,” by the way.

SMITH: Oh, thank you.

MW: And what else did you do?

SMITH: I did the cinematography. I shot it.

MW: Which of those things felt like the most natural fit for you?

SMITH: Editing. I mean, filming was super fun. It was just so intrepid, and my imagination went wild with filming, right? But with editing, it’s something, I just go away. I mean, anyone that edits would know that feeling. It’s just a place, I put on my headphones and I completely tune out. It’s like a natural high, a natural fix where you just don’t want to come out of it. And sometimes there’s challenges within editing, and it takes you out of your zone, but it’s so deep that you could just dive right back in. Yeah, editing was my favorite part, for sure.

MW: Your music is still in there. Are you planning, going forward, to integrate your music-making into the filmmaking? How would you do that?

SMITH: I mean, again, it’s a gift. And I’m glad that I’m not in the position where I have to chase A&Rs and labels and even artists, that this song is cool or this one, it just wasn’t meant to happen that way.

My music has always been kind of eclectic. I’ve had a couple radio situations and multi-platinum situations, but nothing just completely household name. Closest thing was “Shoot Me Down” with Lil Wayne, but even that was different from the rest of the songs on the project. So I’ve always been just lucky enough to make a living from people that get it. But doing film, I get to say, “I want this here, and I want that there.” And how empowering is that? And I feel like I deserve that. I feel like I don’t want to make music and struggle and fight and beg and prove that this is dope. And then again, you can’t make artists what you want them to be.

I was pitching songs that I thought, “This would be great for such-and-such, ’cause it’d make him so cool.” So doing a movie just makes it okay for me to just have fun. But yeah, I’m working on the original soundtrack that I plan to release very soon, before the release of the film, and have been working on that for a while now, so I’m very excited about it. So music is not going to stop. I’m just glad I’m in a position where I don’t have to defend and sell and oversell. It’s a relief.

MW: So the women in the movie, how did you identify who you wanted to cover, and how did you then approach them and get them to do it?

SMITH: Well, originally I found everyone on Instagram. I’m not going to name any names, but I went to some of the popular trans girls. I would go to their comments and I sifted through comments, and was looking for comments that maybe weren’t too preachy, but just sassy, and maybe just a good line that catches my eye. So I was just scrolling through comments for days. And I found a couple of the girls. And then Daniella, I was introduced to by someone that wasn’t ready to do Kokomo City, which was a blessing. When I saw her on her TED Talks, I was blown away.

MW: It’s like, “You’re a philosopher.”

SMITH: How is she not a household name? How? Oh, because she’s transgender, got it. No, so that’s going to change, because she’s brilliant. Very excited about her future.

MW: I actually had a question about something she says in the movie, the statement that she makes, really the whole concept that she puts across, that “the liberated Black woman ain’t got time for the broken Black woman,” which is a radical statement. And I guess referring to a rift in the sisterhood.

SMITH: Sure.

MW: I feel like this movie is working on mending that rift. Is that how you feel about it?

SMITH: Yeah, exactly. I mean, I wanted to make the film primarily for the Black community, and that’s why I didn’t want to name the film anything that alluded to gay or LGBT. I wanted something that just wasn’t going to turn people off right away, because I really want people to heal. I don’t know what this film is going to do for my community or for people. I don’t know. I just know, so far, it’s been very healing and people have opened a lot of closed doors within.

And so to have Black women to champion for me in the theaters and walk up to me — I mean, Black women, you know what I mean when I say that. And I can’t ask for anything more than that. And so if I could get a Black woman to share her thoughts with another Black woman and say, “Hey, you know what? This really touched me in this way.” Or, “I look at this a little differently.” Or, “Girl, you should see this. Girl, you going to trip out,” whatever it takes for them to come together. And even if it’s Girls’ Night and they’re watching it together at home or at the theaters, I really want this to be that.

I want them to feel like they’re part of this new revolution, if you will. We have a lot of issues in our Black community. We have a lot. This is only one part, but it’s so significant because it just draws so many people to “Who’s having sex with who?” and “What’s happened to our men?” and “Why are they gay? Why are they trans?” It’s a lot, but then there’s so much that other Black people are dealing with. This is just what I could bring to the table. So I do hope that it reaches everyone in the community.

MW: I do too. One thing Dominique says in the film that really struck me is that she embraced her transsexuality through sex work, which I thought was also a radical statement. Because — talk about being judgmental — that’s a very non-judgmental thing for the film to put across. I thought in general that the movie was non-judgmental about sex work. What did you want to say about that life?

SMITH: I don’t want to put Dominique on the spot, but the last scene, I asked her to do that, specifically her. She was so apprehensive about it, and obviously, I wasn’t going to push it, but I wanted to make a point to her, because she was second-guessing it from the beginning, and she was pushing back a lot. But I also had to remind her, this is exactly why I wanted to do Kokomo City, because that should be a normal thing that you’re comfortable with, because I’ve seen her nude in other ways, and she seemed comfortable.

But just you, being yourself in your home, the safety of your home with a trans woman filming you, you are uncomfortable with that? I think that was eye-awakening for her. And once I painted that picture, it’s like, well…[gestures, referring to the resulting scene in which Dominique reveals her fully nude body on-camera]. When that happened, it really changed a lot. And I think a lot of people are impacted by that, particularly trans women. Our anatomies are what they are, and if we’re going to normalize this thing, we have to do it. Somebody had to do it, and she did it, and she is an icon for that.

MW: That’s a very powerful moment in the movie. Lenox Love, in the movie, uses a term I’d never heard before but it seems a really simple term, “trans-attracted.” We talk about the terms that we use and don’t use. I believe people don’t like the word chaser.

SMITH: Right.

MW: How do the men who are profiled in the movie feel about “trans-attracted?” How do they refer to themselves?

SMITH: Well, regular niggas just say they’re into them. They don’t use those words. He is around a lot of trans women because he has that nightclub. And a lot of them probably are politically correct. Just politically motivated to correct people when they say things.

Basically, it just means that he’s attracted to trans women. But I’ve never heard, Lo, he would never use that, “I’m trans-attracted.” My boyfriend wouldn’t say those words, I don’t really know what he would say. But some men, which is crazy, some men are not into trans women — they could be into one trans woman. “I’m in love with this person because of who they are.”

Not every man that has a trans girlfriend is just attracted to trans women in general. I know a lot of them that feel that way. But Lenox seemed like he’s pretty clear about what he likes, which is great, too. I’ve always wondered too, how do we not shame men that are just attracted to trans women without calling them chasers? There’s a difference, but it’s hard for me to put that into words right now. There is a difference for sure. It’s almost like you’re just exploiting, you look for, in my opinion, just a sexual relationship with trans women, back after back after back. I feel that trans-attracted means that you have the same amount of respect and honor as you would a cis woman.

MW: I think what Lenox has to say and what Lo has to say in the movie, I think it’s going to affect men who see this movie.

SMITH: Absolutely. They’re saying the same thing, but differently, right? And that’s great about someone like Lo, because he was so real and honest and very transparent with his delivery. And so was Lenox, but they just use different languages, and I think they’re going to reach some of the same people.

MW: So I guess the one really serious question I wanted to ask you about Koko da Doll is how did you learn of her death? And did she have a chance to see the film with an audience?

SMITH: She definitely saw the film. She saw the premiere at Sundance with everyone else. First time for me, watching it on the big screen, just like everyone else. They hadn’t seen anything. By that time, I had seen it for months and months and months and months and months, a million times. And so I specifically asked for all the girls to sit on my row, and pretty much the whole film, I just stared at them, watching every reaction, watching their eyes. That’s what it was all about.

I found out about [Koko’s] passing on Instagram, and I thought it was a joke. Someone said that she passed last night. Because I don’t get that many negative comments, most of the time, I don’t even watch the comments. But I did get one that said, “Koko passed last night. Rest in peace.” I was like, [referring to trolling] “Oh my God, that’s so horrible.” Then I got another one maybe 20 minutes later, and I called my best friend who actually introduced me to Koko. And I asked him, I said, “Well, when’s the last time you talked to Koko?” He said, “About a week ago, but she posted last night.” I was like, “Oh, okay, cool.”

And then I was like, “Uuhh.” I said okay, and then I DMed her. Then I called her and it went straight to voicemail. Someone from her family DMed me shortly after that, and then I… Yeah. It was pretty real then, and very, very difficult to process. It was very difficult. I only met her through the film. We weren’t friends before that. She wasn’t my blood relative, but that was one of the most difficult things I had to process. It was very difficult. She was a very special person.

MW: Well, that also comes through in the film. They all come through really powerfully in the movie. Also the couple, Paris and —

SMITH: Paris and Tommy.

MW: XO Tommy. I love that name. Does he call himself that? Is it XO Tommy?

SMITH: Yes.

MW: So what sort of stories are you intending to take on next?

SMITH: Well, I have something in early development right now, and, ooh, I’m really excited. I have a few projects on the table and I’m just trying to prioritize which one I could do the best right now. And I am working on a narrative, which is getting a lot of interest and looks like it has a home, but the strike and everything. It’s pretty much a go. I’ve already committed to it verbally with the company. And it’s tremendous. It is tremendous. But I have a couple really good cultural documentaries that are just so good.

MW: How soon will we see something?

SMITH: Well, I’m in super, super early development. I just want this to get into theaters and underway, and then I’m full-speed ahead with the next one. But there are actually two documentaries, and they’re so good. So they’re going to come a lot faster than Kokomo City. Kokomo City took about three years because of freaking COVID. I literally just took a year off. I did nothing for a year but B-roll, where I didn’t have to be around people. But these should go by pretty quickly. Super early development but it’s happening.

[Four weeks later, Smith met again to chat with Metro Weekly.]

MW: When last we talked, you mentioned projects you’re taking on now. Have the strikes affected progress? If so, how?

SMITH: No, not at all. [Laughs.] The phone has not stopped ringing. But obviously, I am a human and not AI, so I can only pump out one film at a time, unfortunately. But, trust and believe, if I had the technology to become AI, I would absolutely pump them out every day. So I’m just prioritizing what I want to do next, and I think I’ve gotten to that place where I’ve made up my mind what I want to do next. But, we’ll see. So, no, it hasn’t.

Witnessing this strike and learning what it means and how it’s affecting people, it’s definitely not anything to laugh about, and I want this to just work out. A lot of people are losing a lot of ability to create, and take care of themselves, or sustain what they have. So it’s a very real thing, and I’m grateful that I’m able to continue my journey as a filmmaker at this time. But I definitely wish everyone the best and hope this comes to an end soon.

MW: Do you have any plans to join a guild?

SMITH: Yes, absolutely. Absolutely. I’ll do that once they clean this mess up.

MW: This movie has created a new platform for women like you and Daniella, who already had a platform, and for Dominique and Liyah, and for other women who share similar experiences. I feel, in a way that people teach Paris Is Burning, they will teach Kokomo City. What does that mean to you?

SMITH: It means a great deal to me, because you hope that the ball keeps rolling, where people are passing the torch so that we are always seen, and we’re always evolving, and learning, and creating, and being heard. I think, more importantly, it’s giving queer people the opportunity to really represent themselves in such a way that people can relate to, and feel like they’re not going to be punished for watching it or asking certain questions. I think that we’re in a place now that we really have to step up to the plate as queer people, and own our stories, and tell our stories where people don’t feel threatened by them.

MW: In terms of production of Kokomo City, given that obviously discretion is essential in the business that the women in the movie are in, when you guys were in public, when your crew was filming undercover, how discreet did you have to be, and how did you maintain that?

SMITH: Oh, my God. That’s never been asked before. That’s a good question. I’m just trying to think how to answer that, because, really, I was dressed very… Sometimes if you dress like you’re hiding, people are going to see you. I didn’t want to cause attention, but I also wanted to really show trans women in an everyday living situation too, like walking outside, going to the park, or eating at a cafe.

Me, personally, I don’t hide and run every day doing anything. I live my life as an everyday person, a citizen of the world. But I also had to take into consideration the girls, how they move. But for the most part, everyone was really in their comfort zone and very comfortable. No one threw up any red flags and said, “Ooh, I can’t do that. I can’t go there.” Everyone was pretty relaxed. But also, when I was by myself filming B-roll in the hood, in Fort Lauderdale and Atlanta, it got really intense because I’m in the car with a camera by myself, pulling up on people, driving by, and people were literally stopping what they were doing, looking at me, and I would freak out and I would have to put the camera down, because I don’t know if they thought I was the police or a detective. It was really crazy for me to do that. But, it was exciting too.

MW: That’s documentary filmmaking.

SMITH: Yeah, I loved it! I loved it. One hand on the steering wheel, one hand on the camera.

MW: I can see the image. Thanks for that. On your personal story, where did you grow up, and, like what did you study in school, for example?

SMITH: I grew up in a little spot in Miami called Opa-Locka. It was really hard in the ’90s because, a lot of times, I went to bed on the floor because my grandmother, when we’d hear gunshots, she would run in the room and tell us to get down on the floor. They’d be shooting so long that I’d fall asleep on the floor to gunshots. It was a very familiar, but yet scary, circumstance, hearing gunshots so loud and so close to your home.

But I also had a beautiful childhood, in terms of, I was surrounded by a lot of family, and we went to church, and we played outside, and all those things growing up back then. In school, I had to choose either a music program or visual arts, so I chose visual arts. For years, I used to do paintings, watercolor, pencil drawings. I won all types of awards across the country for my visual arts, painting and stuff like that, when I was a kid from 4th grade to 12th. Then I really started getting deep into music.

When I was 16, I went to New York. I was homeless. I had a duffel bag about the size of a coffee table, and I went straight to 72nd and Broadway in New York and just sat there, dead of winter. I heard some subway singers for the first time in my life. I’d never witnessed anything like it. They were singing, and I would see them often at that station. I had no means of financial anything. My parents, no one knew that I had moved to New York. I lied and told them I was going to go to Atlanta to a cousin’s, and didn’t do that.

So here I am in New York, homeless, and maybe $20 in my pocket, and I started singing, harmonizing, with these older guys that were in the subway, and I became a subway singer. After they heard me singing, they asked me to join them. I have pictures of me in the subway, singing on the South Ferry. Then I ventured on my own, singing on my own in the subway. I eventually was able to get money to rent a room. Then I started writing, and I eventually got offered a publishing deal from Sony, by someone seeing me singing in the subway. So Sony ATV offered me my first publishing deal, from hearing one song that I had wrote and produced, and they gave me a publishing deal for like $65,000, which was crazy because I was eight months behind in rent. That money came in handy right there.

MW: That whole thing, that’s a musical unto itself.

SMITH: That is a musical. That’s funny. I didn’t even think about that. I’m going to write that down.

MW: I give these out for free. I am happy to hear of the beauty of your childhood. Did your family support your separate journeys, of becoming an artist and becoming fully yourself?

SMITH: They supported me being an artist the best way they could. None of them were smart enough to be my manager or to say, “Damn, D’s really talented. Let’s really pull together and make this happen, or support D’s talent.” Growing up in a Black family, sometimes our talents and our emotions are just completely overlooked and dismantled, just because it’s not something that Black people invest in. We’re not really encouraged, a lot of times, emotionally, or even talent-wise, in a Black household. It’s just something very hard to obtain.

As far as my identity, no, I wasn’t supported at all. Even though my grandmother, bless her heart, she knew, she just didn’t say it. She said everything else except, “You’re gay.” She was just so sweet, my God. But I got beatings. I got punished. I got embarrassed. I got hit by my father constantly, for him suspecting that I was gay. I would be the only boy walking around the neighborhood saying, “Child, please.” They knew, they just wanted to beat it out of me. It didn’t work, it actually made things really worse, because I became what we call a DL, which obviously hurts a lot of people, including yourself, and it wastes a lot of time.

But when you’re embarrassed and ashamed, and you have no outlet to express who you are, you bottle it in, and you take it out on other people, and you become a freaking weirdo by being DL because you don’t know how to handle it. So no, I wasn’t at all supported identity-wise, not at all. Then I was a faithful member of my church. I would be at church for three days out of the week. I loved church. I’m pretty flamboyant, I think. But I knew how to tone it down, too. It’s just very weird. I learned how to tone it down. So yeah, I didn’t have that support system.

MW: In my experience, Black folks have really, really good gaydar, but it’s not something they always want to communicate about.

SMITH: Right. No. No, no, no, no, no, no. I think the times are changing now, even though it’s hard for people to accept, and they think it’s an agenda. I don’t know what that means, but I wish I had that when I was a child. I wish I had someone to protect me from the beatings that I got from my dad, or those scary, threatening conversations about who I better be and better not be. I wish I had someone to protect me from that. I didn’t. This movie and my platform will do that for someone, because I will always inspire and encourage people to find support and help if they’re being abused emotionally for who they are.

MW: You talked about how shame leads people to do things that hurt people. That describes a lot of the anti-trans, anti-queer policies we face today. Given how politicians and legislators have been making anti-trans policies their platform, I’m curious, because it’s something I think people talk about, are there places in this country where you’d be concerned to travel, to live?

SMITH: There’s no place I would not move to. I mean, if there’s a place that’s just not aesthetically pleasing to look at, that’s one thing. But I would never not move somewhere out of fear. But that’s just me. I would never let a politician, I would never let a speech, I would never let a law scare me into not being myself. Those days are completely over, and I want to encourage gay, and queer, and trans people to not start. Do not even open that gate of that fear.

But me, personally, I honestly don’t even see it. I don’t feel it. I’m not even bothered by it. I just think we have to stay focused, get as many allies [as we can], and also recognize and acknowledge and lift up our allies, and stop saying who’s against us. I think it’s time for us to actually twist it, and show how many people do like us, how many people do want to protect us, rather than us focusing on who’s after us. Because I promise you, we’re not the minority. We’re really the majority, and we have to start acting as such.

Kokomo City opens August 11 in Washington, D.C. at the Alamo Drafthouse Bryant St. NE. Visit www.drafthouse.com/theater/dc-bryant-street.

To find when it will be playing nationally at a theater near you, visit www.magpictures.com/kokomocity/screenings.

Follow D. Smith on Instagram at @truedsmith.