At the corner of Madison and Jefferson in Chicago stands a 100-foot-high baseball bat, constructed in a lattice pattern from 20 tons of steel. It is the largest sculpture created by the artist Claes Oldenburg, a man from whose mind sprang any number of super-sized objects: a 45-foot tall clothespin in Philadelphia, a 29-foot-long spoon in Minneapolis. In Kansas City, you’ll find a shuttlecock the size of a steeple.

Oldenburg, who died in July 2022 at age 93, was one of pop art’s most prominent exemplars. He was also a distinctly Chicago artist, a distinction that received only scant acknowledgement in local obituaries. “C.O. equals Chicago,” wrote Oldenburg in his notebook, playfully connecting his initials to the city that nurtured him when he was young and continued to loom large in his imagination as he became a globe-trotting art world luminary.

Indeed, Oldenburg’s ties to the city went far beyond one humongous bat. Much commentary on the artist starts with his 1956 arrival in New York City, as if he had sprouted—fully formed—from the brow of abstract expressionism. But Oldenburg’s Chicago roots were deep and tangled. He was raised in the city from the age of seven, attended the Latin School through 12th grade, and (after college) returned to become a journalist at the famed City News Bureau, attend classes at the School of the Art Institute, and contribute dozens of illustrations for Chicago magazine. Even after his later move east, Chicago often served as a municipal muse for his groundbreaking body of work.

Oldenburg’s father became Swedish consul general in Chicago in 1936, and the family—toting along with them heirloom 18th-century Scandinavian crystal chandeliers and golden clocks—moved into 44 E. Bellevue (a residence that has since been replaced by a large condo building). “When Claes arrived in Chicago,” writes art critic Barbara Rose, “he spoke no English, and communication with other children was extremely difficult. Not surprisingly, he led an even richer fantasy life than most children.” That fantasy life was a petri dish for the adult artist’s oeuvre: “Everything I do is completely original,” Oldenburg wrote in 1966, as he was taking the New York art scene by storm. “I made it up when I was a little kid.”

The young artist, left to his own devices in his father’s offices, engaged in elaborate, fanciful world-building; he chronicled the geography and culture of an imaginary island, which he called “Neubern,” in endless maps, models, newspapers, and even movie posters. Rose—a primary biographer of Oldenburg—asserts that, “Like the work that Oldenburg was to produce as a mature artist, Neubern was a parody of reality, providing a counterpart cosmos that paralleled the real world instead of imitating it.”

The scenery outside his third-story bedroom window provided more fodder for his imagination. The fire hydrant on the street (which he called a “fireplug” in the vernacular of the day) proved to be a locus for drama and a cause for contemplation. “I saw firemen vengefully run their hoses through the windows of a car parked by the plug in winter, causing the car to become a solid block of ice,” he reminisced in his notebook years later. “The details of the plug give a sketch of brutality—the locked caps, their chains, the blunt construction.” In the late 60s, the fireplugs that intrigued him as a child would become the template for hard sculptures, soft sculptures, proposed monuments, and even cuff links.

From third grade through high school, Oldenburg attended the private Chicago Latin School for Boys, a 15-minute walk north from that first Chicago home. He and his classmates would play baseball and stickball on the roof of the building, which is still home to the school’s pre-K through fourth grade students.

Courtesy of Latin School of Chicago

When he was in eighth grade, the yearbook reported “Claes Oldenburg insists he is misunderstood by practically all the teachers.” By his senior year, he was editor of three school publications, on the student council, and playing for the private school league champion football team.

Those were not, however, the only “extracurriculars” of Oldenburg’s high school education. He would check out Chicago’s strip joints—perhaps the same ones where another Chicagoan, a teenage Bob Fosse, had worked as a tap dancer just a couple years earlier; the burlesque spirit he encountered there would later infuse his visual aesthetic, notorious for its ribald evocations of breasts and genitalia.

Courtesy Deirdre English

Oldenburg would return to those clubs when he came back to Chicago as an adult. As his first wife and close artistic collaborator Patty Mucha recalls, “Claes could justify what I thought was his dirty-old-man habit by using these images to make some outrageously shocking, yet beautiful drawings.”

Oldenburg went to college at Yale University, but upon graduation, he was drawn back to his hometown. He soon got a job at the City News Bureau, covering cops and courts at the legendary local wire service. (His tenure there came just after Kurt Vonnegut’s and just before Mike Royko’s.) Oldenburg’s job description spanned the mundane to the thrilling. Longtime editor Arnold “Dornie” Dornfeld recalls in his book on the Bureau, “Claes Oldenburg was terrified that he was going to get chewed out because he had to push the editor’s frozen car by hand for more than two blocks before he could get it started,” but also that Oldenburg used his father’s connections “to get into the exclusive Swedish Club on the north side, something no other reporter had been able to do, to get information on a crazed gunman who was running amok in the building.”

However, as Oldenburg said later, this kind of journalism seemed “a very unidealistic pursuit, you know, and there was no future in it. . . . So then, after about a year and a half of that, I resolved to become a professional artist.”

That impulse led Oldenburg to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he took classes on and off for a few years, painting alongside key figures of the midcentury Chicago art scene: Robert Indiana, H.C. Westermann, Robert Barnes, and Irving Petlin. Outside school he would pal around with Leon Golub, June Leaf, and George Cohen.

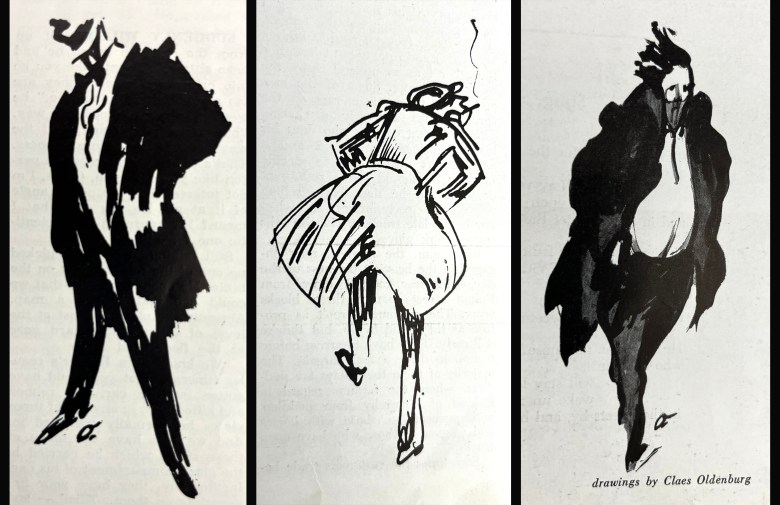

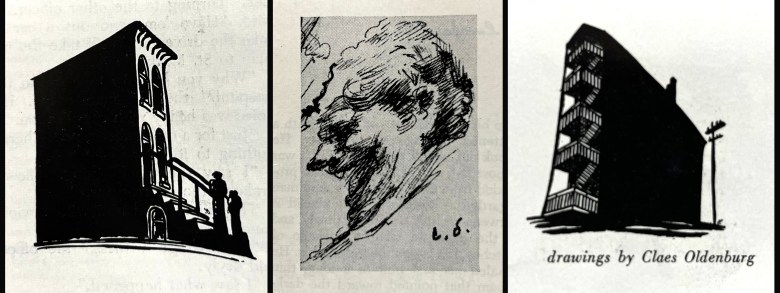

His most significant job in this period was at the 1950s iteration of Chicago magazine, first as staff artist, then as contributing editor. (That publication, founded by Maurice English, has no connection to the Chicago magazine of today.) From March 1953 through February 1956, Oldenburg contributed at least 33 drawings to the monthly. These are Oldenburg’s earliest professionally published works, and they have never been included in catalogs of his art or discussions of his emerging style.

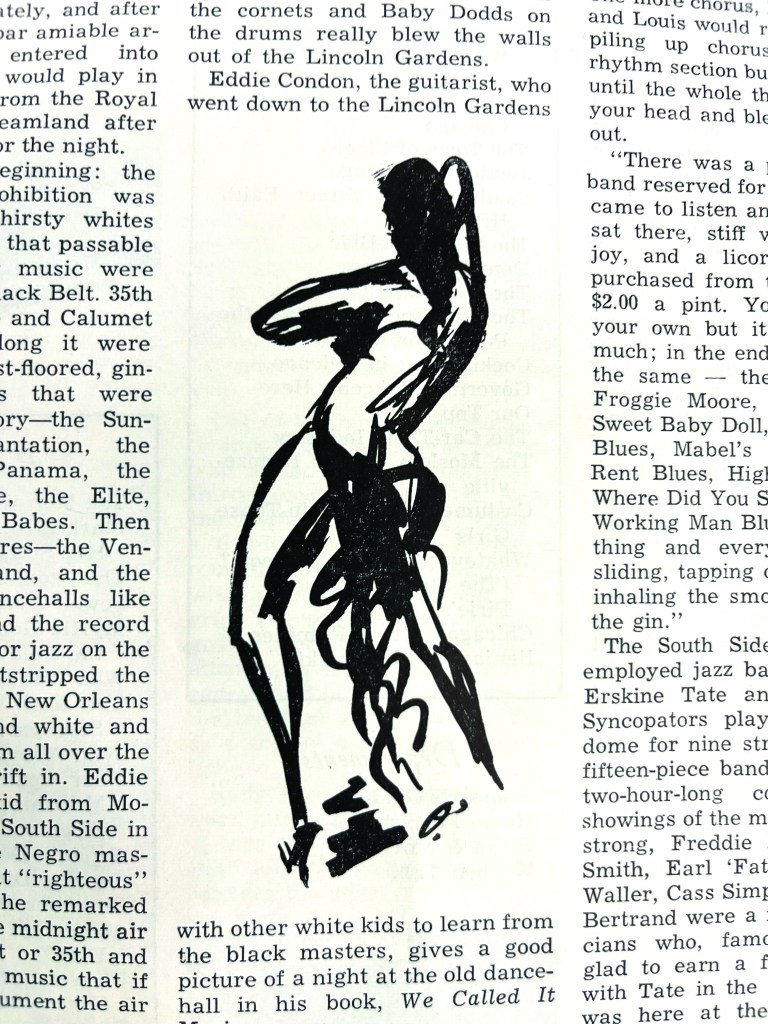

Courtesy Deirdre English

Even as Oldenburg became famous for his sculptural (and eventually monumental) works, drawing—which he would define as “the accidental ability to coordinate your fantasy with your hand”—for him remained at the heart of it all. But most, if not all, of the originals of the Chicago magazine drawings were likely destroyed. “I went through my drawings about two years ago and destroyed approximately 75 percent of them,” he told an interviewer in 1965, “because I felt that whatever I had said had been re-said in a better way.”

Courtesy Deirdre English

Courtesy Deirdre English

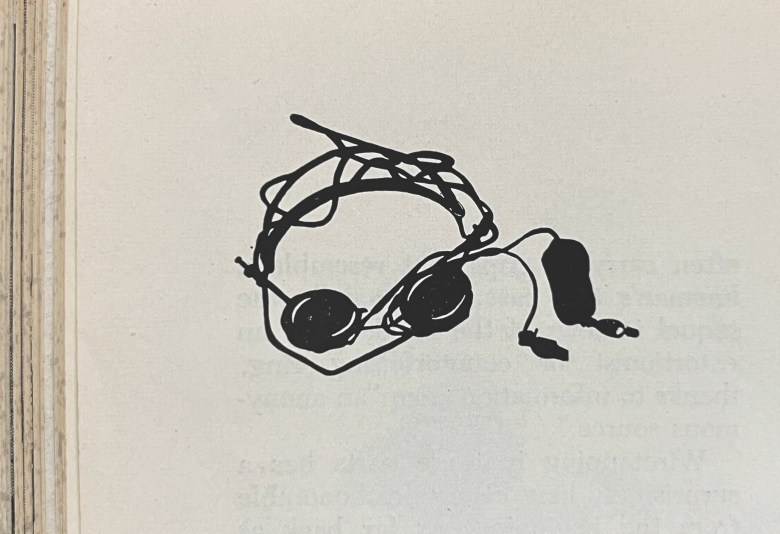

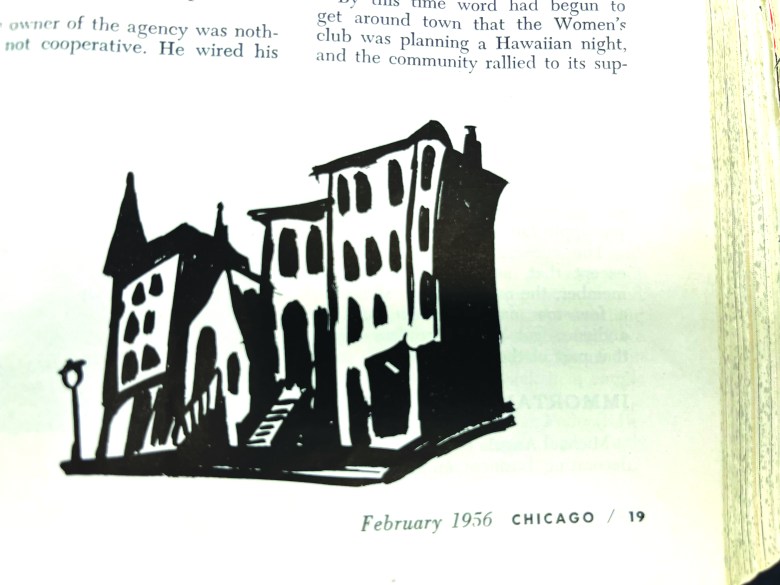

Oldenburg’s magazine work provides tantalizing clues to his future direction as an artist. A streetscape from the February 1956 issue shows pliant, expressive buildings. A pair of headphones illustrated a 1955 article about wiretapping in Chicago. Here, in a harbinger of his future approach, he gives a certain personality to the headphones, transforming an everyday object into an amusing, anthropomorphic form.

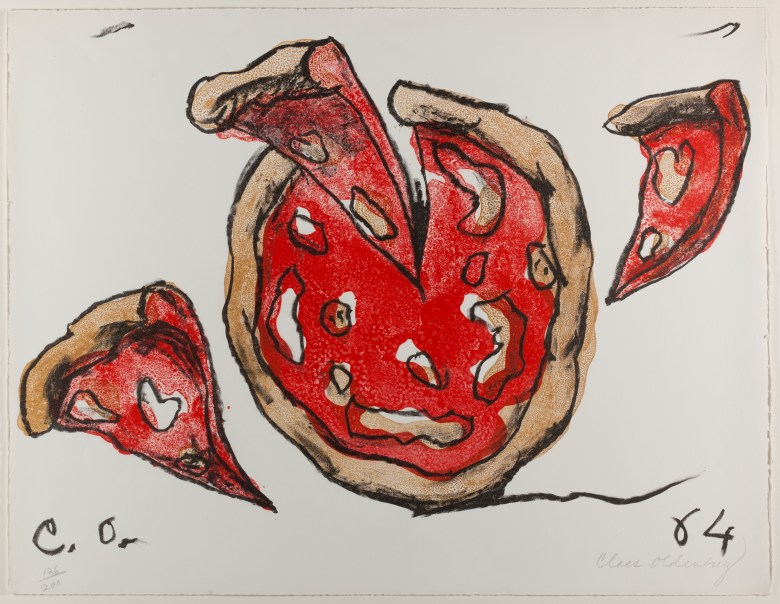

© Claes Oldenburg. Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

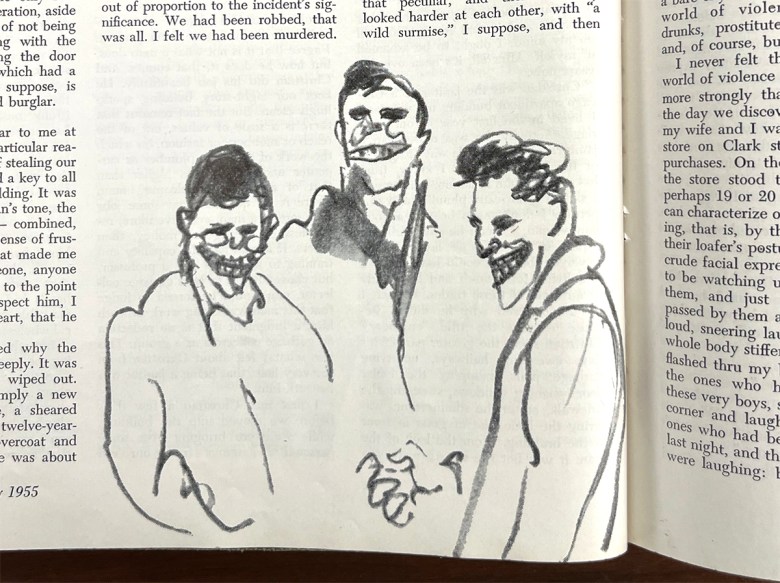

At this time, Oldenburg had his first exhibition, showing work in the bar of Club St. Elmo, at State and Maple. The proprietor, St. Elmo Linton, delighted in both exotic cuisine (rattlesnake, rooster combs, and fried agave worms were on the menu) and the work of young artists: several Art Institute students had their first exhibitions there. Oldenburg contributed “a group of satirical drawings” inspired by a story by one of his favorite authors, Nelson Algren. The story, “The Face on the Barroom Floor,” is a witty yet horrifically violent tale that takes place “in a dingy speakeasy on the wrong side of Van Buren Street.” Brutality and humor would continue to worm their way into Oldenburg’s mature work. “I am for an art,” he would write in 1961, “that imitates the human, that is comic, if necessary, or violent, or whatever is necessary.” We don’t know what the work exhibited at Club St. Elmo looked like, but some of Oldenburg’s caricatures for Chicago may give us a hint.

Courtesy Deirdre English

The Club St. Elmo show was the first of a half dozen Chicago-area exhibitions over the next couple of years. But in 1956, Oldenburg relocated to New York City. He later wrote a farewell poem—a rejoinder to Carl Sandburg’s “Chicago,”—to the city that had raised him and nurtured his nascent artistry. (It is reproduced in Robert Haywood’s book on Oldenburg.)

goodbye Chicago

you big piece of iron

you hard jaw

you black crusher

you swell sweeping eye

your brain of macadam

you clunker of boxcars

you eye-blackener

teeth-smacker

asphalt roarer

goodbye

In New York, Oldenburg’s painted sculptural work—rough-hewed from burlap, muslin, plaster, and wire and presented as installations in nontraditional gallery spaces—earned him acclaim. In his early New York years, Oldenburg worked in an aesthetic in some regards sympatico with his cohort from Chicago. Like him, Chicago artists of the 50s and 60s tended to turn away from abstraction and embrace figurative work. “I come out of Goya, Rouault, parts of Dubuffet, Bacon, and the humanistic and existentialist imagists, the Chicago bunch,” Oldenburg wrote in 1960, “and that sets me apart from the whole [Hans] Hofmann-influenced school.”

By the time Oldenburg exhibited work back in Chicago in 1963 (at the Art Institute and the Richard Feigen galleries), he had already established himself as a central figure in the intersecting New York visual and performance art worlds.

That intersection was on full display at the University of Chicago’s Lexington Hall in February of that year, where Oldenburg and colleagues presented a multimedia “happening” entitled “Gayety: Composition for Persons, Objects, and Events.”

Given his background, it is not surprising that his oeuvre would have a theatrical bent. As a child, his singing-teacher mother got him a walk-on role in an opera “wearing a little suit,” he participated in high school dramatics, and he incorporated performance in a 1954 residency at Ox-Bow, the Saugatuck, Michigan, art school a couple hours from Chicago. “I remember the first performance involved a raft on the water, which we sank.”

In New York, Oldenburg had fallen in with like-minded practitioners who were devising happenings. His creations (or as he described them, parallel re-creations of a collective reality) were carefully scored series of actions utilizing props and costumes of his own design: “something,” he said, “like a living poem or objects in motion.”

With “Gayety,” the artist’s hometown finally got to see one. “I want to create a civic report on the community of Chicago, in the way I see it,” he wrote in the script. “This is like the civic projects one did in sixth grade.”

Credit: Department of Urban Renewal Collection, Special Collections and Preservation, Chicago Public Library

Oldenburg and his 23 cast members created a metaphorical map of Chicago, with a welder representing the Gary steel plants to the south, sinks representing Lake Michigan to the east; a central Loop area; and diagonal playing areas to represent the diagonal streets of Chicago, like Milwaukee or Archer avenues. “The place in which the piece occurs, this large object, is . . . part of the effect,” Oldenburg wrote, “and usually the first and most important factor determining the events.” Despite 20-degree-below-zero weather, around 150 audience members attended each of three evenings of performances. At the end of the hour-long performances, a “huge stuffed airplane”—meant to evoke the airplanes that hang from the ceiling of Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry—was lowered from the rafters and “thrown onto a group of spectators.”

As the decade progressed, Oldenburg’s schemes became grander in scope, and he began to conceive monumental projects for urban spaces. “The main reason for the colossal objects,” he wrote, “is the obvious one: to expand and intensify the presence of the vessel—the object.”

Chicago was a destination and an inspiration for such colossi. “I think I like to go back to Chicago to establish contact with my growing up there,” he told filmmaker Michael Blackwood, “but also with the sense of space and infinity that the great lake can present, out of which the city rises very clearly like a series of sculptures, or perhaps a gigantic cemetery.”

In his mind, Oldenburg created an alternative Chicago: instead of Graceland Cemetery’s simple headstone for architect Louis Sullivan, he imagined a “broom closet in monumental scale” containing a “600-foot-long figure of the reclining Sullivan;” instead of the Chicago Tribune Tower, he dreamed up an enormous clothespin; instead of Buckingham Fountain, a giant windshield wiper or a lumpy punching bag; in answer to Picasso’s 1967 steel sculpture on Daley Plaza, a soft canvas-and-rope version. Comiskey Park would be shut down and reopened as a ghost version of itself, a Memorial to Baseball. For the end of Navy Pier, Oldenburg’s “feasible monuments” included a pair of women’s boots, a bed-table lamp, a rearview mirror to reflect the city, and an inverted version of the fireplug that had fascinated him as a child.

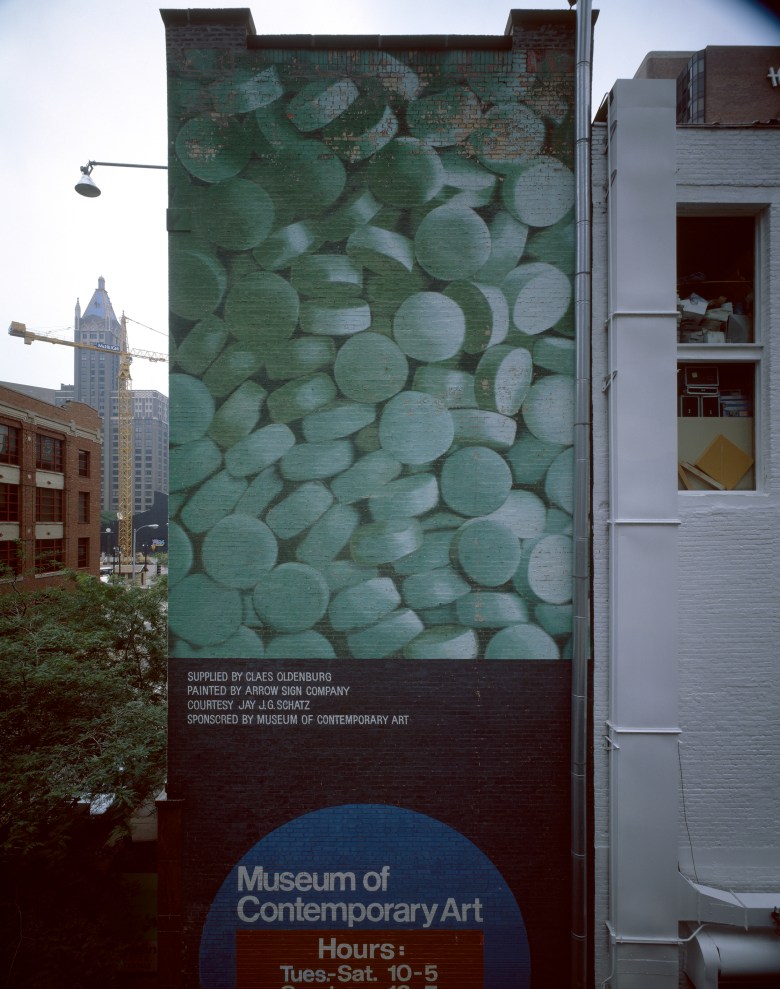

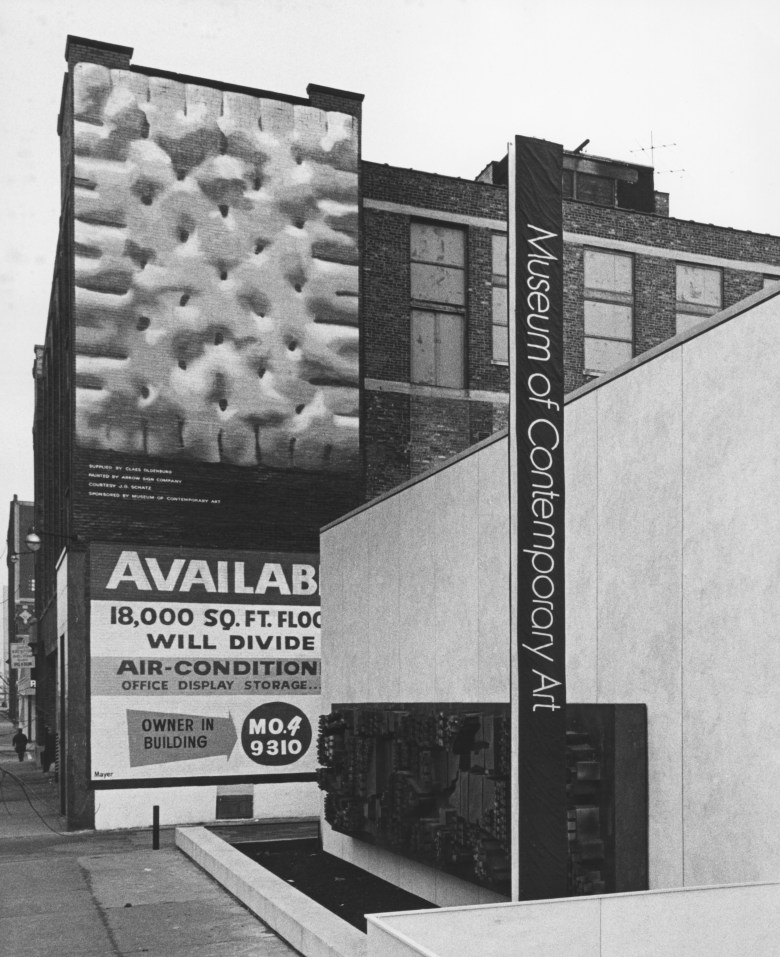

None of these proposals were actually constructed, but the establishment of Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in 1967 gave Oldenburg a venue to show off some of his visions. “Claes Oldenburg: Projects for Monuments” was one of two inaugural exhibitions for the upstart museum.

Credit: David Van Riper, © MCA Chicago

Oldenburg’s relationship with the MCA was to continue, including his contribution to their “Art by Telephone” exhibition in 1969, considered to be a seminal moment for conceptual art. For his contribution, Oldenburg telephoned museum staff each day to dictate messages, which were then written (like a seer “getting messages from the other world”) on a blackboard in the galleries. An Oldenburg exhibit on “The Mouse Museum and Ray Gun Wing” would follow in 1977.

© MCA Chicago

© MCA Chicago

Credit: David Van Riper © MCA Chicago

The contrast between the rather anodyne “Pop Tart” of 1967 to the more fraught “Frayed Wire” of 1969 reflected a significant shift in how Oldenburg saw his hometown. The police violence at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago had altered Oldenburg’s conception of the city and his artistic vision for it.

He had intended to attend the August convention as an observer, even procuring press credentials for the event. But when then-Mayor Richard J. Daley ordered the brutal suppression of protesters, Oldenburg was caught up in the riot. “In Chicago, I, like so many others, ran head-on into the model American police state,” he wrote to his gallerists Feigen and Lotte Drew-Bear. “I was tossed to the ground by six swearing troopers who kicked me and choked me and called me a Communist. Fortunately my head wasn’t split, my wrists broken, or my groin gored, but I got the message—the evil in Chicago (which is considerable) had been mobilized to destroy the values I came looking for.” Oldenburg informed Feigen that the experience had unsettled him, and that he wanted to postpone his upcoming exhibit at Feigen’s Chicago gallery: “A gentle one-man show about pleasure,” he said, “seems a bit obscene in the present context.”

Feigen responded by filling the October slot intended for Oldenburg’s show with a “Richard J. Daley” protest show, featuring not only Oldenburg but a who’s who of American art: Lee Bontecou, Christo, Donald Judd, and many more.

The reaction to the exhibition was predictable. As Feigen writes in his memoir, “Daley’s people obviously noticed, because despite the burly bodyguard Oldenburg hired to escort our gallery director, Lotte Drew-Bear, to and from her apartment, some goons came into the gallery and trashed the place.”

Oldenburg’s proposed monuments for the city now took on a new tone. His punching bag images assumed an altered meaning for him, now that “Chicago’s finest” had punched and kicked him, His Feasible Monument to be Scattered in a City Park: Fragments of Nightstick Contact commemorated that beating; even something as insubstantial as smoke was “a good subject for a sculpture there,” Oldenburg wrote. “In April, 1968 [after the assassination of Martin Luther King], I watched parts of the city being burned. The people who set those fires intended it to mean something. That could be called making a monument.”

After becoming Chicago’s punching bag in 1968, it is quite the twist to see Oldenburg return to the city wielding a giant baseball bat in 1977. At the unveiling of Batcolumn, acting mayor Michael Bilandic welcomed the artist who had been the victim of his predecessor’s vicious crackdown a decade earlier. Now, the forces of power were arrayed behind Oldenburg. Second Lady Joan Mondale—an Oldenburg fan—struck a patriotic note at the monument’s unveiling, saying, “How fitting, how uniquely American, that the visual arts should flourish in a city that is also a center for commerce and industry.” Oldenburg rhetorically hedged his bets a bit: “The Batcolumn could be called a monument to baseball and, undoubtedly, to the ambition and vigor that Chicago likes to see in itself.” The United States Navy Band played. Chicago Cubs greats Ernie Banks and Billy Williams were on hand, and Banks joined the Second Lady in releasing dozens of white balloons, printed with thread designs to resemble baseballs.

By now, Oldenburg was an establishment figure, and criticism came from the political left. Across the street from the unveiling, artists calling themselves the Surrealist Movement of the United States protested, calling Oldenburg “a miserablist lap dog” and the Batcolumn a “serviceable symbol of repressive authority. . . . When the workers of Chicago tear down this five-story nightstick, then we shall have a game worth playing.”

Oldenburg, however, was no longer equating his work with the police truncheons of ’68. He now said, “I don’t always see the things in my work that other people see. To me, Batcolumn is just a simple object, very pure, but also very suggestive. It’s always a matter of interpretation, but I tend to look at all my works as being completely pure.” He was thankful, he said, “for the opportunity to create such an unusual project without compromise.”

In reality, the project had faced a history of compromises. His original conception of a giant bat, in 1967, was not exactly “pure form.” He imagined it outside the new Latin School at the corner of North and Clark, and it was to be “kept spinning at an incredible speed.” According to Rose, Oldenburg “maintains that his Bat Spinning at the Speed of Light, to be located in front of the school he attended as a youth, originated as an anti-masturbation fantasy—a monument that burned your fingers if you touched it.” Feigen tried to make the idea a reality, but—not surprisingly—funding was unavailable.

The instigation for Batcolumn finally came in the form of a commission (including $100,000 for the artist) from the U.S. General Services Administration, for a sculpture outside the new Social Security Administration building on Madison. The funding garnered controversy. Wisconsin senator William Proxmire gave the project one of his “Golden Fleece” awards, presented to government programs that fleece the voting public. “Baseball is indeed our national game,” he said. “A statue of Babe Ruth, Ernie Banks, or Bill Madlock, the Cubs’ current star, would have some merit. But a $100,000 bat paid for by all of America’s taxpayers is a strikeout with the bases loaded.”

“I don’t want to be critical,” Oldenburg replied, “but somebody wrote that Proxmire’s hair transplants had gone too far down into his brain.”

Oldenburg toyed with various ideas for the sculpture—an iteration of his fireplug, a giant spoon, a Dutch boy cap—before settling on the (nonspinning) bat. Various contingencies continued to compromise Oldenburg’s schemes: due to property lines, the sculpture had to be moved closer the the building than he would have liked; the color red was rejected because it had already been used for Alexander Calder’s Flamingo outside the federal building. But eventually, the engineering was worked out; sections of steel cage were fabricated, welded together, and sandblasted, and the whole long thing was trucked, horizontally, from Connecticut to Chicago. There, it was lifted into position by cranes from the aptly named Midwest Steel Erection Company, and it joined the fabled skyscrapers—real and imagined—of the city.

Credit: Kirk Williamson

On July 18, 2022, Oldenburg died in his New York home. The New York Times printed an extensive obituary and, a day later, an appraisal of his work by critic Deborah Solomon. Artforum and Art in America published significant tributes. Even the Kansas City Star, the Dallas Morning News, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Los Angeles Times, and the Provincetown Independent published original articles celebrating the artist’s connections to their cities. Obituaries referenced his Chicago upbringing and his Batcolumn, though most skipped over his postgraduate period in the city, when he was cutting his teeth as an artist; Solomon elided those years, writing simply, “In 1956, after graduating from Yale University, Oldenburg moved to New York.”

Chicago media were even less forthcoming, with the local dailies both publishing the Associated Press obituary. The most significant Chicago-centric look at Oldenburg came weeks after his death from venerable Tribune columnist Rick Kogan, who—on the day he wrote the piece—decried the lack of coverage in an interview with the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. “Claes Oldenburg died, and we don’t run in the Tribune—sadly—the number of obituaries we used to. We did run one of him, but it barely mentioned that he grew up here, for Christ’s sake! . . . And I’m thinking, ‘Wait, this guy deserves more than this.’”

Kogan is right. Oldenburg’s death has been met with a collective shrug from the “City of Big Shoulders.” Given Chicago’s central role in Oldenburg’s personal genesis and artistic evolution, a more thorough reckoning is warranted. In ways big and small, Chicago—with its skyscrapers and museums and graveyards and strippers and smoke—primed Oldenburg to create a new kind of art: one that remade everyday objects in new forms, forms that were often funny, erotic, political, theatrical, and imbued with connections to Oldenburg’s personal history.

Courtesy Deirdre English

As a child in Chicago, Oldenburg cooked up the imaginary island state “Neubern,” and the same exuberant impulse and meticulous world-building went into his reconception of Chicago as an adult artist. His Chicago magazine illustrations, his Chicago happening, his “feasible monuments,” and finally his Batcolumn, all in some way generated an alternative Chicago, one that captured the city as Oldenburg conceived it. Chicago’s Oldenburg transformed the international art world through his public monuments; Oldenburg’s Chicago—with its melting buildings and giant fireplugs and soft airplanes—represents a different kind of transformation, one that accords with Oldenburg’s “single-minded aim,” as he wrote in 1960, to create “a parallel reality according to the rules of (my) fantasy,” a “geography of the human imagination.”

related stories

On Exhibit: a roomful of Daleys

Richard Feigen remembers the 1968 Democratic convention well. Feigen, a Chicago-trained artist who now works in New York but owns a gallery here, recalls the surprise that swept the city–first at the demonstrations, then at the bloodshed. Feigen, though, was not surprised. “Everyone was astonished by what happened,” he says, “except for the art community.”…

Reading: Exterior Decoration

If bronze and stone were no more substantial than the status of artists in this city, the public sculptures of Lorado Taft would have crumbled long ago.

On Class Oldenburg

In those years that we showed Claes Oldenburg in Chicago, I always wanted to place a large outdoor piece in his hometown. When the Latin School, of whose 1946 football team Oldenburg had been a star, moved to its new location on North Avenue, I talked to the architect, Harry Weese, about placing an Oldenburg…