Co-edited by 2 ASU professors, ‘La Plonqui’ looks at the work of Margarita Cota-Cárdenas

In the first line of her Wikipedia entry, Margarita Cota-Cárdenas is described as “a voice for Chicano literature.”

That hardly begins to appreciate the contributions Cota-Cárdenas made to Chicano culture, including becoming the first professor at Arizona State University to develop a Chicano literature class.

She also raised three children on her own, became an accomplished poet and author, and founded the publishing company Scorpion Press, which was funded by the National Endowment for the Arts and designed to publish works by bilingual, bicultural women.

Cota-Cárdenas’ life is being celebrated in a book titled “La Plonqui: The Literary Life and Work of Margarita Cota-Cárdenas,” co-edited by Vanessa Fonseca-Chavez, an associate professor of English at ASU, and Jesus Rosales, an associate professor of Spanish in the School of International Letters and Cultures.

The book was published in late September. Cota-Cárdenas’ work — and her life — will be celebrated at an event held from 3 to 5 p.m. on Thursday, Nov. 9, in Ross-Blakley Hall.

ASU News talked to Fonseca-Chavez about the book and the impact Cota-Cárdenas made.

Editor’s note: The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Question: For those who aren’t familiar with Cota-Cárdenas, how would you describe her contribution to Chicano life and literature?

Answer: She was one of the first Chicano writers who emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. She published two novels, “Sanctuaries of the Heart” and “Puppet: A Chicano Novella.” She also produced three books of poetry. So she’s had kind of a 40-year career being one of the major literary writers in Chicano literature.

Q: Why was her Chicano literature class at ASU important?

A: What was happening is that you had all of these Chicanos who had emerged from the Chicano movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and students needed to see themselves reflected in the classes they were taking. Chicano literature as a field of study did not exist before the 1960s, but Chicanos did. So you had people like Cota-Cárdenas start to develop these classes within the Spanish program within the School of International Letters and Cultures.

It was Jesus Rosales who first taught “Sanctuaries of the Heart” in a graduate class that I took on Mexican American women writers that kind of really opened my eyes to her larger contributions. I had already read “Puppet” when I was a master’s student at the University of New Mexico, and that one kind of blew my mind. It was very experimental, and that’s just the way she writes most of her books of poetry and her novels.

Q: How is her writing experimental?

A: It’s a lot of English and Spanish mixed together. For a long time in Chicano literature, you would produce Spanish with a glossary, or you would italicize it to make sure that your reading audience knew that it was Spanish. You would provide direct translations within the text, and that’s not something Margarita cares to do. So when I say she’s kind of unapologetic and experimental, she uses the language as she would use it in everyday life.

There’s not a lot of writing patterns that lend themselves to direct translations into English. Her words will flow into other words and phrases. And, again, Spanish and English are mixed constantly throughout. She’ll even make up words if the occasion calls for it. So you can’t dissect her work that easily. And I think that’s really lovely about it.

Q: In reading her Wikipedia page, she seems like a remarkable woman. She was a single mom, she thought of becoming a nun, then she was a published author and important contributor to the Chicano community. Am I reading her right?

A: You are. As part of the collection in the book, there is an interview with her where she does talk about her different career options, becoming a mom early on in her life, and then ultimately her decision to dedicate her life to poetry and to writing. What’s interesting is that within just Chicano literature writ large, there is this expression of limited options for females. You would get married or become a nun. Those were essentially the two options available to you. So we really like these Chicano writers who chose a different path for themselves. And what a tremendous impact they’ve had.

Q: Did Cota-Cárdenas open the door for other female Chicano writers?

A: I would say so. Chicano culture is very patriarchal, just generally speaking. But she doesn’t have a filter in her writing. She directly calls people out. And she doesn’t apologize for calling it what it is. I think that’s very brave, especially during her time period. I think it gives permission for scholars like myself to be the same way. If we see these injustices, even within our own families or other cultures kind of perpetuating in our own communities, we can say, “Hey, you have to cut that out.”

Q: So, she was a trailblazer.

A: Absolutely.

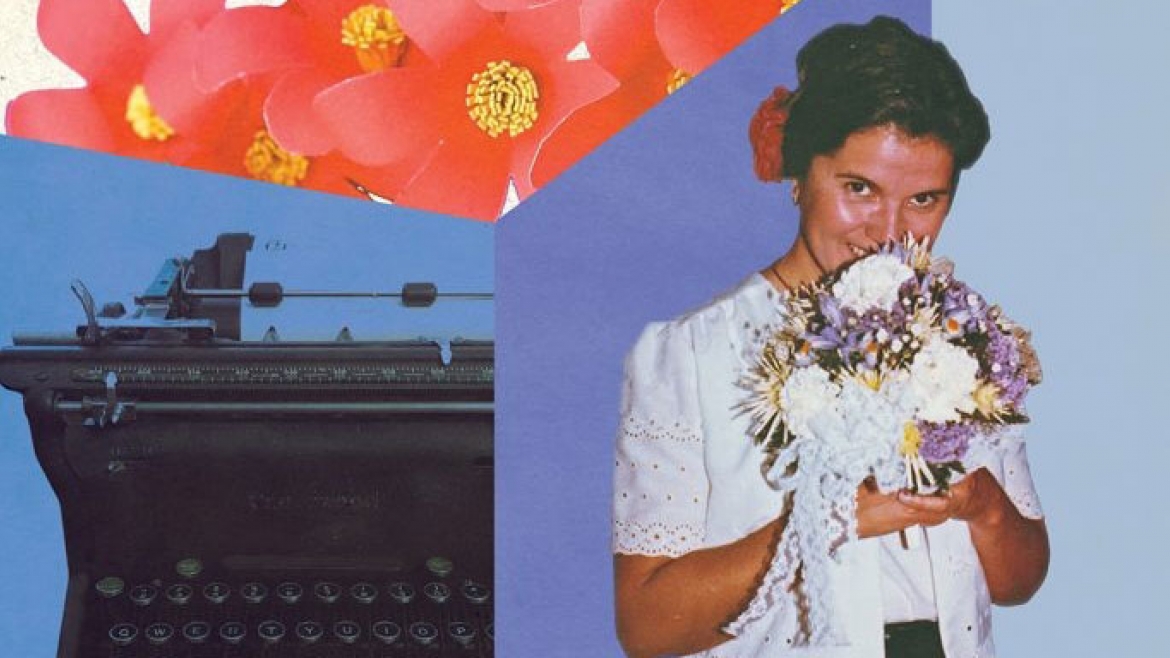

Top photo: Margarita Cota-Cárdenas featured on the book cover for “La Plonqui.”

Composer Paola Prestini breathes new life into Hemingway masterpiece

For composer Paola Prestini, Ernest Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea” is a story she’s wanted to tell her whole life. Originally born in Italy, Prestini grew up in both Nogales and Tucson, Arizona.

“Water has always played a role in my life — I’ve explored its power often, how it nurtures, heals and separates. My father is an amateur yet devoted fisherman. In our unspoken relationship, I’ve wanted to understand his choices, his inner life, which I believe he has only told the sea,” Prestini said. “It became that much more exciting for me to explore the themes of this work.”

The world premiere of contemporary opera “The Old Man and the Sea” will take the stage at ASU Gammage on Nov. 4. Photo courtesy ASU Gammage

Download Full Image

“The Old Man and the Sea” is a contemporary opera that will have its world premiere at ASU Gammage Nov. 4. Created by Prestini, librettist Royce Vavrek and director Karmina Šilec, it presents a dual track of storytelling by combining the original short story with portraits of author Ernest Hemingway’s life. The cast brings to life the original book characters Santiago and Manolin, and amplifies the tale by bringing in a chorus who bears witness to the storytelling onstage. Phoenix Chorale and Prestini’s own husband, renowned cellist Jeffrey Zeigler, will be a part of the premiere.

It is narrated by Hemingway, played by a baritone vocalist who doubles as the character of Santiago, and the bar owner, La Mar. When “The Old Man and the Sea” was published in 1952, Hemingway hadn’t written a significant literary work for over a decade. The audience sees him in moments of doubt as he creates his masterpiece.

This contemporary opera is over a decade in the making. Along the way, Prestini called upon longtime friend and ASU alumna Beth Morrison to produce the piece and walk this journey alongside her.

“There’s just nobody who does new work the way Beth does,” Prestini said. “I’m very grateful to have a producing partner who understands the way I work.”

Two stories are told at the same time — Hemingway’s life as he is writing the novella, and the story of “The Old Man and the Sea” itself. These twin threads bring the audience all the way to the end of Hemingway’s life. Whether the audience has read the short story before or not, there is something to be had for everyone.

“When you leave the opera, I think you’ll have a more profound understanding of Hemingway’s state of mind, but also what he was feeling when he was writing that story,” Prestini said.

Regarding the new direction with such a well-known work, Prestini hopes the layered music of the opera is something that people haven’t heard before — that it keeps the mind thinking and keeps the heart healing.

“The music itself has electronics, which adds a lot of variety and color, and bringing together different styles keeps it eclectic and fresh, which I think excites a new audience,” she said.

Prestini notes that everybody comes to art from a very different perspective and life experience, and that the best art is complex and tells the audience different sides to help them see the messiness of life.

“This story takes on many different perspectives and tells you what it means to have a legacy, what it means to live in communion with the environment and what it means to be an artist capturing that feeling onstage,” Prestini said. “As someone who grew up in Arizona, it’s really meaningful for me to have a place that supports new work the way ASU Gammage does, and I’m just so grateful for it.”

Written by Alexis Alabado