Isca in Red, 2021, Oil on linen, 24 x 20 inches, 61 x 50.8 cm, Signed, titled, and dated (verso)

Isca in Red, 2021, Oil on linen, 24 x 20 inches, 61 x 50.8 cm, Signed, titled, and dated (verso)

Sebastian Blanck

New York NY

By DONALD KUSPIT, August 2023

When do we call a human face beautiful? Every face is fit for purpose in its parts, but only perfect proportions and colors in a well-balanced harmony deserve that title of honor: beauty.

— Le Corbusier (1)

Le Corbusier would have fallen in love with the classical Venus: the traditional goddess of love had a perfectly proportioned face, as the beautiful Venus de Milo, ca. 150 BCE-ca. BCE makes clear. It was also probably more alluring—less aloof–than it is today. Considering the fact that ancient sculptures were once colorful, as a remarkable exhibition of them at New York’s Metropolitan Museum made convincingly clear, her face probably had just the right amount of cosmetic color to underscore its natural beauty and suggest that she was desirable. Her beautiful Renaissance sisters, Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, 1484-1486 and Titian’s Venus of Urbino, 1532-1534 clearly have colorful faces: their lips are painted red and their cheeks covered with red rouge, making their beautiful faces more attractive, not to say seductive, adding to their sexual appeal. Similarly, Rubens’ Venus in Front of the Mirror, ca. 1614-1615 wears red lipstick and red rouge on her face and nothing on her body, for it needs no cosmetics to heighten its beauty, emphasize its desirability.

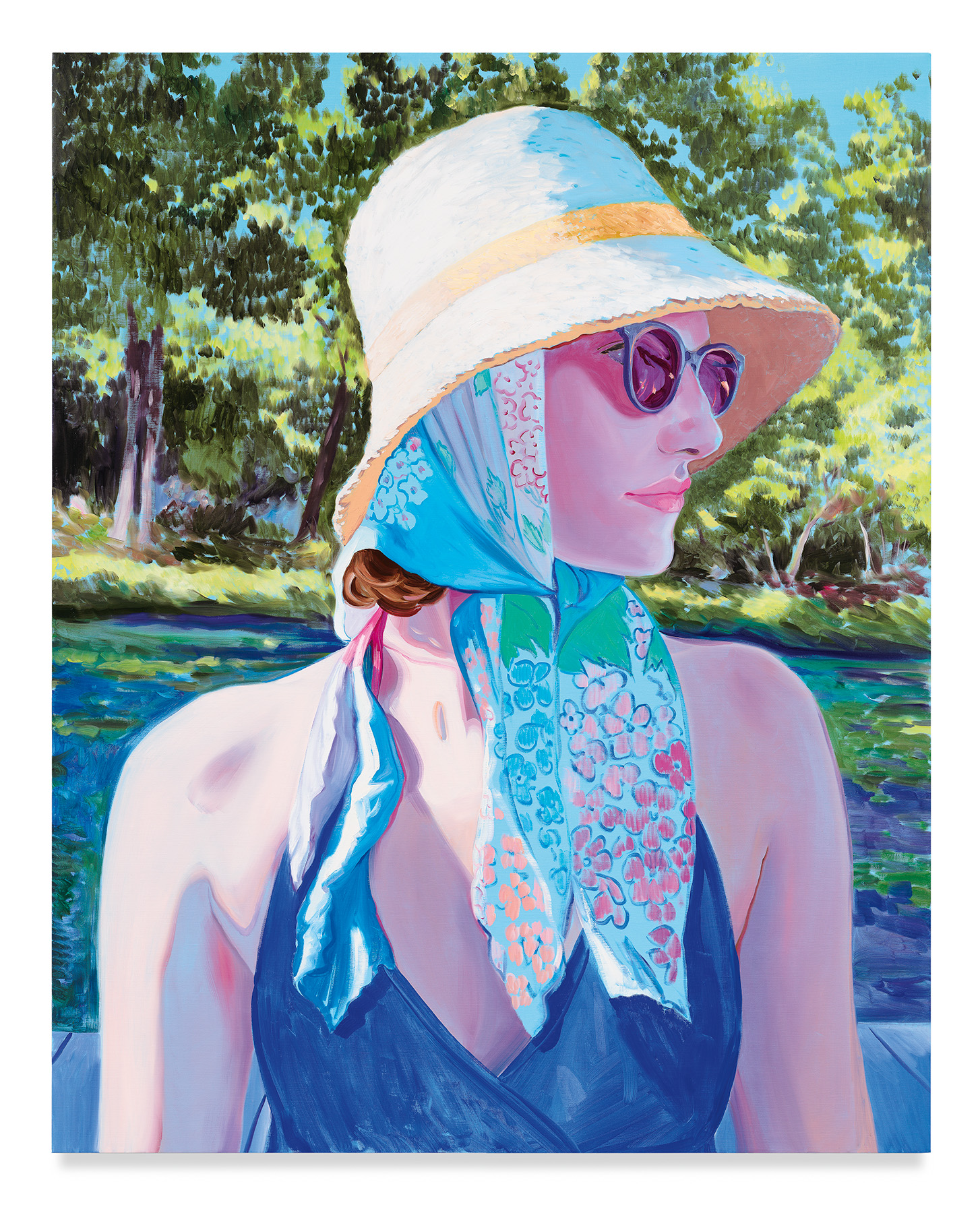

What are to make of Sebastian Blanck’s classy new Venus, her breasts hidden by a white blouse, suggesting her virginity, her beautiful face richly colored in pink shadow in Hot Tea, 2023? It’s a hot face, the face of a woman simmering with desire, but coolly drinking hot tea, the sky blue cup suggesting her control, the self-containment and self-control of a proper young woman, in the end more sophisticated than sexy. Shielded from the hot sun by a straw hat, almost as luminous as the sun, her eyes shielded from its relentless light by sunglasses, in effect a seductive veil, adding to her mystery, she is a picture of cool seduction, a sort of sophisticated femme fatale. But it’s teatime, and tea and sex don’t mix, unless what’s being offered is Tea and Sympathy, to allude to Robert Anderson’s 1953 play. And there’s nothing sympathetic about her.

Hot Tea, 2023, Oil on linen, 80 x 64 inches, 203.2 x 162.6 cm, Signed, titled and dated (verso)

Hot Tea, 2023, Oil on linen, 80 x 64 inches, 203.2 x 162.6 cm, Signed, titled and dated (verso)

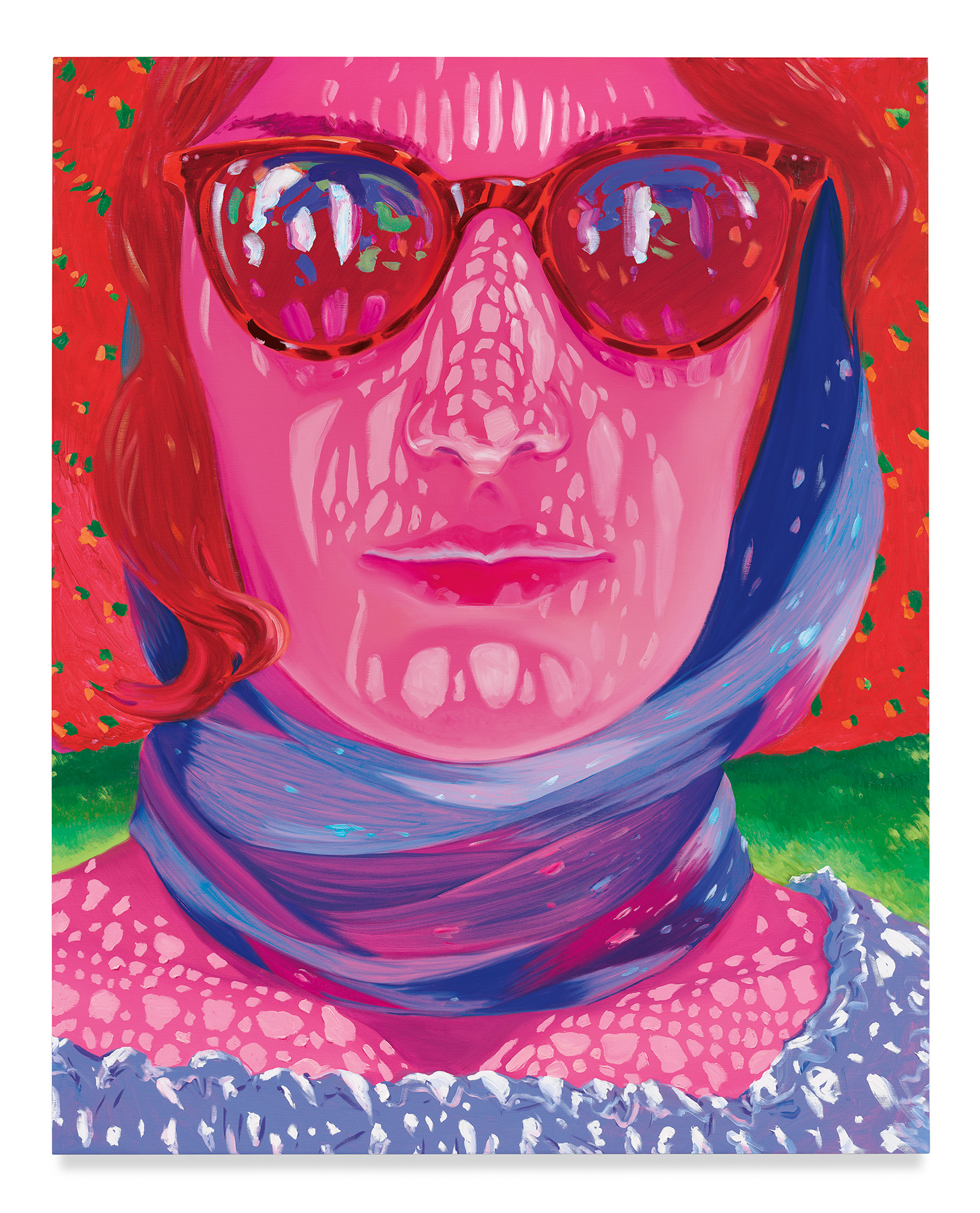

The same pink face—its eye-catching hot pink, a symbol of alluring femininity, suggests that this Venus, nouveau riche, as her classiness suggests, is perhaps a would-be femme fatale, perhaps Baudelaire’s “implacable Venus”—wearing the same sunglasses, and covered with a richer, thicker pink shadow, confronts us In Straight Ahead, 2023. She stares us down, a fierce Medusa ready to turn us—certainly the male spectator–into stone. Confronting—castrating—the male gaze, she seems more feminist than feminine. Provocatively in our face, rather than discreetly turned aside, as the lady-like Venus is in Hot Tea, she becomes an emblem of female autonomy. But one wonders, no doubt absurdly, if Blanck’s unconscious has painted the head of the Medusa, cutting it off like a new Perseus, holding it up for us to see as Benvenuto Cellini did. My reading of the painting is perhaps—probably?—absurd, but it stands out of the other paintings in the series as an anomaly. This peculiarly ugly face cannot be the same beautiful face of Venus that we see in the other portraits. It is worth noting that the Venus of Titian and Rubens look at the male viewer, hoping to catch his appreciative eye, but Blanck’s Venus never does, except in Straight Ahead, where she stares him down with a crushing confrontational look.

Isca (Sun Hat Profile), 2021, Oil on linen, 72 x 60 inches, 182.9 x 152.4 cm, Signed, titled and dated (verso)

Isca (Sun Hat Profile), 2021, Oil on linen, 72 x 60 inches, 182.9 x 152.4 cm, Signed, titled and dated (verso)

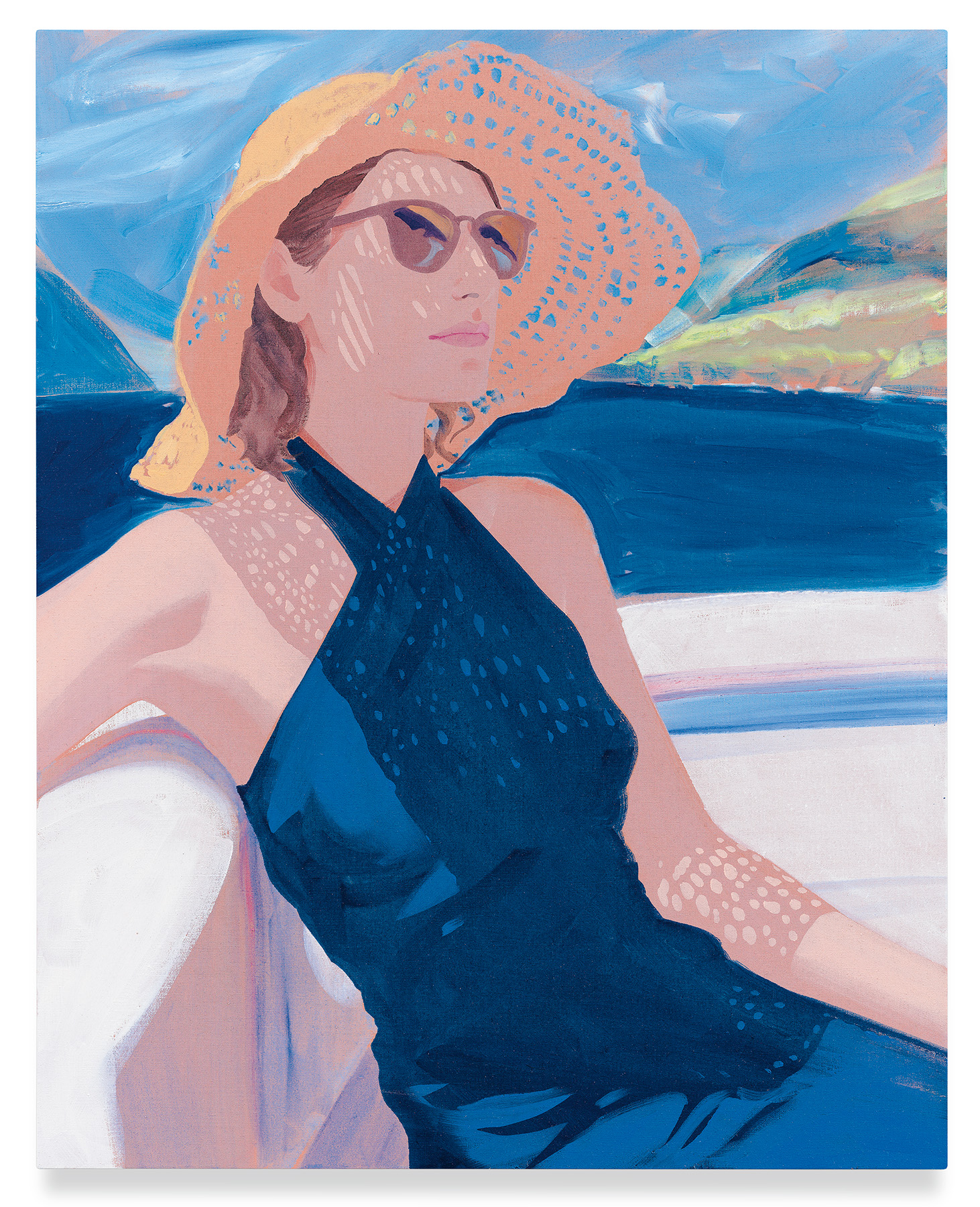

In Isca (Sun Hat Profile), 2021 brown shadow protectively covers her face like a mask, suggesting that it is completely suntanned, despite her protective sun hat. The brown shadow, seemingly more than skin-deep, is punctured by an array of white holes, each a sort of idiosyncratic tache,(2) arranged in rows. A streamlined version of them forms a seeming infinitely extensive grid—an abstract pattern–on the hat while emphasizing its curvilinearity. It is an ingenious formal touch, oddly confirming the formality of Isca’s profile pose. The rows are multiplied on the shoulder, also brown—tanned—and also forming a grid-like pattern. It quixotically drapes the shoulder like a knitted shawl, paradoxically making the immaterial shadow seem materially real and permanent rather than transient. The neck is also brown, one luminous tache, barely a full-fledged gesture, appears on it, like a casual beauty mark. There’s not a hint of color on the skin of the shoulder and arm. The light blue of what seems to be a low-cut shirt or blouse—but it turns white as its straps reach over the shoulder—suggests that the sky is blue and the bright yellow sun hat suggests the intensity of the sun’s light. Is it high noon? The flourishing raw gestural nature in the background is at odds with the thin young self-contained—inhibited?–woman, suggesting she’s not a ripe Mother Nature. She’s a far cry from the classical Venus, proudly exhibiting her desirable body. The traditional Venus is always full-bodied—sometimes to a Rubenesque ripeness–however sometimes exquisitely slender—like Titian’s Venus, proudly displaying her perfectly proportioned body. But she never seems to be on a diet, as the fashionably thin Isca in Her Sun Hat, 2018 seems to be. We never see her naked body. And it’s clearly not much to see—it certainly can’t hold its own with the beautiful body of the ancient Venus—as the seemingly anorexic Isca in Red, 2021 indicates. Is she an intellectual, as the eyeglasses—not sunglasses—she wears in Yellow Hat, 2022 suggests? She’s cool and calm Looking Out At The Lake, 2023 through her sunglasses, a picture of sophisticated indifference.

Looking Out at the Lake, 2023, Oil on linen, 80 x 64 inches, 203.2 x 162.6 cm, Signed, titled and dated (verso)

Looking Out at the Lake, 2023, Oil on linen, 80 x 64 inches, 203.2 x 162.6 cm, Signed, titled and dated (verso)

Unlike the traditional Venus, she’s emotionally remote, however wildly colorful, as in Sun Hat Blue Reflection, 2022, Purple Shadows, 2023, Isca in Her Sun Hat, 2018, Sun Hat, 2018. She wears red pants in Isca in Red, 2021, suggesting she’s hot between the legs, red being the color of passion, but a white sweater hides her small breasts and thin body, suggesting she remains peculiarly virginal however passionate—which is the paradox of Venus, who remains transcendentally pure–sacred however profanely sexual. Isca’s left hand rests on what seems to be a red bed and her right hand rests on her left thigh. Her pose is sexually suggestive; this is hardly the same reserved, sophisticated, mature woman hiding behind sunglasses and sun hat, looking very cool as she turns her head away from us while Looking Out At The Lake. It is hard to realize that the glamorous, sophisticated Isca In Her Sun Hat and fashionable dress and looking into the distance as though to announce her detachment—certainly distancing herself from the viewer perhaps in haughty disdain—and virginally pure as her very white skin suggests and cool rather than red hot as her sky blue dress and the calm blue sea behind her suggest–is the same person as the girlish Isca in Red. In none of the paintings is she the voluptuous, full-bodied, naked Venus of Titian and Rubens—the beautiful goddess of love promising sexual pleasure. Is Isca more mind than body as her eyeglasses seem to suggest? She may wear the right clothes and strike a sophisticated—calculated–pose, but she is not the “Propitious Queen of Love,” as Lucretius said Venus is, but a sort of cool narcissist.

Isca in her Sun Hat, 2018, Oil on linen, 30 x 24 inches, 76.2 x 61 cm, Signed, titled and dated (verso)

Isca in her Sun Hat, 2018, Oil on linen, 30 x 24 inches, 76.2 x 61 cm, Signed, titled and dated (verso)

But she has other virtues—aesthetic virtues, which undo her passivity and expressionless features. Blanck’s paintings are not psychologically insightful—Blanck’s female figure doesn’t seem to have much of an inner life—she seems too eager to strike a pose—but they are brilliantly “advanced” paintings, for the best of them ingeniously reconcile what Kandinsky called the “two poles” of art, “Abstraction” and “Realism,” more particularly “the purely artistic” and the “objective.” Color is purely artistic, as his analysis of the “psychology of color” makes clear, along with tachistic gesture, as his discussion of “the line’s liberation from that most primitive of instruments, the ruler,” opening the way to “freer graphics“—”unmechanical expression,” that is, tachism, in all its expressive variety, confirms. Informing the object—the human object in Blanck’s case—they subjectify it, that is, give it emotional character, as Blanck does with his female figure—dramatize it until it seems to become beside itself with feeling, spontaneously alive, and so a True Self, rather than merely socially given, and so a False Self, to use the psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s distinction. Posing with her teacup and hiding behind her sunglasses or demurely reclining, Isca is a false self. Absurdly covered with colors and taches, sometimes completely, as in Straight Ahead, she becomes true to herself, for she is showing—expressing–her feelings on her face without embarrassment and defiantly, without fear of social ostracization. She is no longer the proper young inhibited lady she is in many of the other portraits. One other painter–Mitchell Johnson—makes aesthetically convincing abstract realist pictures, but where Johnson works on a macroscopic, “public” level, using broad planes and geometrical complexity to do so, and is more interested in space than figures, Blanck is more interested in figures than space, and works on a microscopic, “private” level, using color and complex tachism to reconcile the opposites, with determined intensity in the more conspicuously tachistic works, charged with strong color and complex forms. Simply said, Blanck makes the aesthetic character of the figure emphatically manifest, with that giving it the artistic credibility it lost when the modernist critic Clement Greenberg dismissed it as impure rather than pure art, more pointedly aesthetically inferior to abstract art. But abstraction has become a reified cliché, allowing the figure to gain renewed credibility by showing that it has inherent aesthetic quality, which is what Blanck does. The aesthetic works in subtle ways to give unconscious meaning to objects; it is self-defeating when it becomes an end in itself as it does in non-objective art.

Straight Ahead, 2023, Oil on linen, 80 x 64 inches, 203.2 x 162.6 cm, Signed, titled and dated (verso)

Straight Ahead, 2023, Oil on linen, 80 x 64 inches, 203.2 x 162.6 cm, Signed, titled and dated (verso)

Apart from pure color, abstract in itself, which conveys the unconscious feeling in the self-conscious young woman in High Tea, Blanck uses an array of tachist devices to give the painting abstract credibility, and with that aesthetic authority: marks, sometimes geometrically arranged, as in the pointillist dots on her hat, sometimes casually, seemingly indiscriminately arranged, as in the bluish shadow on her white blouse, and sometimes forming a sort of geometrical grid on the upper half of her face. They are all compactly together in Straight Ahead, a tour de force of abstract aesthetics, all the more brilliant for seamlessly integrating the purely aesthetic and the objective, to recall Kandinsky’s words. Isca (Sun Hat Profile), with its contrast between the repetitive lines of pointillist taches on the sun hat and the brown grid of eccentrically geometrical forms that cover Isca’s face and shoulder, subtly flattening them, is an ingenious masterpiece of geometrical abstraction. Sun Hat Blue Reflection is more wildly—eccentrically—abstract, the variety of taches, pink on the face and neck of the figure, blue and pink on what seems to be her sun hat, flanking the abrupt contrast between her sky blue sunglasses and pink nose and chin, with a vividly red lipsticked mouth between them, is another tour de force of abstract realism—or is it realistic abstraction? For me, these four paintings are the most original, innovative works in the exhibition. The abstract mask she wears in Straight Ahead is hardly glamorous. As I have suggested, it turns her into a monster. The other paintings are convincing portraits, glamorizing—and with that superficially idealizing–the model, but less aesthetically ingenious and “conceptually” rigorous. They are not “postmodern abstractions,” but a sort of stylized realism.

If modernist abstraction began with Kandinsky’s separation of the objective and the subjective, and the dubious Solomonic wisdom with which he discarded the objective and emphasized the subjective—it occurred when he famously became blind to the reality of Monet’s Haystack but experienced, in a kind of bizarre epiphany, its color as a dazzling, emotionally exciting end in itself—then postmodernist abstraction reintegrates the objective and the subjective, the naturally real and the subjectively expressive aesthetic. Kandinsky realized the error of his schizoid experience of Monet’s painting, his splitting off and repressing, indeed, denying the object, and elevating subjective color to the be-all and end-all of art—it is the argument of On The Spiritual in Art, written in 1910 but published in 1912, later arguing for their re-integration, evident in many of the works illustrated in the Blue Rider Almanac, 1912, where he notes “the welcome complementation of the abstract by means of the objective and vice versa,” “the Great Abstraction” and “the Great Realism,” the “two poles ” of art that “open up two paths, which lead ultimately to a single goal,” for there are “many possible combinations of different juxtapositions of the abstract with the real,”(3) as Blanck’s abstract realist paintings brilliantly demonstrate. WM

Notes

(1)Quoted in Rudolf Arnheim, Toward A Psychology Of Art: Collected Essays (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1972), 197

(2)”Tache,” the French word for stain or blemish or spot or patch, owes its art historical importance to the fact that an art critic wrote that Manet’s Music in the Tuileries Gardens, 1875 was composed of taches. A viewer apparently complained about the painting, saying that it was incoherent, but Zola said that if the viewer stood at a certain distance from the painting the patches would converge to form a figure and scene, that is a realistic rather than peculiarly abstract painting, and with that a peculiarly absurd painting—a painting that was at once realistic and abstract. Taches are the ancestor of the expressionist gesture. Tachisme is a French style of abstract painting that developed in the 1940s and 1950s, supposedly in response to and in aesthetic competition with American abstract expressionism. French Tachisme is sometimes called Lyrical Abstraction to contrast it with more aggressive American Epic Abstraction, which violates—not to say eviscerates–the figure, as de Kooning’s paintings of woman do, in contrast to Blanck’s abstract paintings of women, which respect her whole figure while making its aesthetic character radically manifest. The tache can take the geometrical form of the pointillist dot, as it does in Blanck’s Sun Hat, 2018, or be used to construct a grid, as it does on the face and neck of the young woman wearing the sun hat, or expand into a kind of amorphous plane, gestural fragments of it covering her nose, lips, and chin, like some awkwardly applied cosmetics. As is always the case, Blanck’s abstract forms, gestural or geometrical, or ambiguously both at once, are ironically realistic. In this article I am using the word “tache” for any non-objective, non-descriptive aesthetic detail that disturbs, unsettles, undoes the representational order—a sort of loose thread that can pull it apart or threaten it, not only with incoherence but meaninglessness, as the subversive taches that the perceptive French critic saw in Manet’s Tuileries painting do. A tache can be a point or line, both of which Kandinsky discusses at length, and also a grid, in a sense a grand geometrical tache, for it is a patchwork of small geometrical taches that repetitively echo its form, as the eccentric grids on the faces and bodies of Blanck’s females do.

(3)Kenneth C. Lindsay and Peter Vergo, eds. Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994), 242