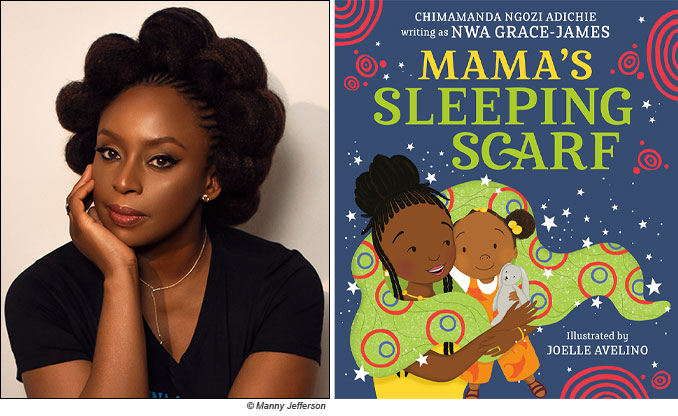

From landmark TED Talks to award-winning novels to profound critical reflections, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s work has taken many forms. With her forthcoming publication, Mama’s Sleeping Scarf, Adichie delves into a new category: children’s books. Illustrated by Joelle Avelino, Mama’s Sleeping Scarf follows a Black girl named Chino as she embarks on a day of exploration and play at home with her father, grandparents, and stuffed bunny. The centerpiece of Chino’s games is her mother’s beloved sleeping scarf, an object that signifies and strengthens Chino’s connection to her mother while she is away at work. We spoke with Adichie about the inspiration she took from her own life for the book, the promising changes she’s seeing in the literary landscape, and the unexpected challenges and delights of writing for children.

In an Instagram post, you noted that Mama’s Sleeping Scarf was inspired by a day in the life of your daughter. How did the narrative come to you and why did you want to write Chino’s story in particular?

I’ve often been asked why I don’t do children’s books, and usually I would respond by saying that my vision is too dark. And so I worry that if I started to write a children’s book, I would somehow invariably have somebody die. [When] I had my daughter, I [spent a lot of time] reading to her and buying kids’ books, which made me start thinking about children’s literature. I was thinking maybe I should try but I wasn’t sure what I wanted to write about. There was just one of those very, very simple moments where I’m holding her. She reaches out and pulls at my hair. My hair was braided. And I thought, this is such a small moment but it’s going to go and it’s going to disappear from our memories forever. And then I started thinking about the idea of preserving memory. I realized I want to write a book for kids but also a book in which I try to preserve a memory for my daughter—but then I didn’t do anything about it.

And then two years passed. Then one day we’re in Lagos and it’s just a happy ordinary day. My parents were there with us. My husband was making a smoothie. And I just thought, how about I capture this for my daughter? She was about four at the time. I realized I wanted that day to be the memory that I try to remember for her. So, I just made little notes, and I didn’t do anything with it again for another two years. I started thinking about it again after my father died, and that’s actually when I decided that I would write it. So, it became two things: creating this memory for my daughter, but also celebrating what for me is an ideal version of family, which is an extended unit, and remembering my parents.

How did the process of writing Mama’s Sleeping Scarf differ from your work for adults?

I remember thinking when I started, “Oh, it’s a children’s book. It’s going to be easy.” But actually, I found myself stumped in the middle. You start writing and you realize that the rules for children’s books are quite different. My style isn’t to be so direct but you really have to be direct with children. I felt that I had to shift my register. In some ways it humbled me because I realized it’s not easy to do. I also practiced it on my daughter—the first draft I read to her, she was utterly bored, and so I thought, this is not good. It made me think differently. Writing a picture book really requires an entirely different mindset.

How do you feel about writing for young readers now that you’ve written a children’s book?

Oh, I’m still terrified. No, I’m actually thinking about doing more. I hope to follow the character of Chino and still keep it loosely based on my daughter. I’m hoping the next book will be where Chino is maybe seven.

Hair and mother-daughter relationships are both powerful themes in your work. Can you talk about the importance of centering the story around a sleeping scarf, and how it reaffirms Chino’s bond with her mother?

The mother character is kind of based on me. I always sleep with a scarf, as do most of the Black women I know in the world. I want to make the ordinary things of Black people’s lives just become a normal part of everyday literature. I remember when I first came to the U.S. and I was surprised by how I would get my hair braided and my friends who were not Black would be like, “Oh my God, your hair grew so long!” And I would think, my goodness, they really do not know this sort of very basic thing about Black women’s lives. When I was thinking about the scarf, I was struck by how that can become a symbol of a number of things. It’s a metaphor for a mother and a daughter having this wonderful bond, but for me, it’s also a way of celebrating Black women in a very simple, ordinary way.

That’s beautiful. It’s funny how our worlds can seem smaller than they need to be. There are things that are so obvious and mundane to so many of us that are completely new to other people.

That is why I feel so strongly about being invested in this project of making our lives not be small.

Literature has a powerful role in that. In your TED Talk, The Danger of a Single Story, you spoke about how your experience reading Western children’s books as a child influenced what you thought was possible in literature. Do you think that the publishing industry and what’s available to children has changed since your talk was released?

Yes-ish. I did that talk in the early 2000s so I think things have changed a bit, but I also worry that a lot of the changes can sometimes feel almost performative and temporary. I’m hopeful because I can see in the publishing world there’s a lot more talk about diversity and inclusivity, and I just hope that it translates to long-term change. I’m not sure yet but I’m hopeful. There’s still work to be done.

By writing children’s books that feature stories and characters that are not generally centered in the literary canon, do you hope you can help change that?

I think [through] the very act of writing a children’s book that’s set in Nigeria and that’s about the ordinary life of a family I am contributing to diversifying the stories that are published as children’s books. But I don’t want to be the only person who made books diverse. I want to be one of many. I don’t want Nigeria to be the only African country that people know about. I’m very committed to this idea of diversity, but I also think that it makes me uncomfortable to be seen as somehow the “icon of diversity,” because I think even that shows that we still have a long way to go.

Working with a visual artist on a book must have been a new experience for you. Can you talk about your collaboration with Joelle Avelino and how you feel her artwork illuminated your story?

I think she’s an absolute star. I was sent samples of different illustrators’ works and my love for her work was almost immediate. I looked at what she’d done and I just thought, yeah, this is it. I felt that she captured African life. She really paid attention—she wanted to look at pictures of my family, and she wanted to look at pictures of our house here in Lagos. Then, when she sent the first batch of the illustrations, I was almost in tears. There’s a page that has the grandmother character kissing the little girl, and it makes me cry every time. Honestly, I’ve never been as ridiculously emotional about anything I’ve done as I am about this little book, and I think in some ways it surprised me.

Do you feel like Mama’s Sleeping Scarf is more directly connected to your life and to the people in your life than other books you’ve written?

Yes, apart from my memoir about my father. This is the most personal thing I’ve written. I think that is why I’ve felt so emotional about it, because it’s this thing that I’ve done as a person who no longer has parents, while having had a life deeply anchored by my parents. There was just this huge shift for me and this book is about that.

It sounds like the book was inspired by your daughter and fueled by not only by that relationship but also by who you are as a mother and what is important to you in your relationship with your daughter.

Yes, absolutely. What’s important to me and my daughter is communication, playfulness, and joy in the ordinary.

Another striking element of the book is Chino’s independence and her ability to make a world for herself while her world is still—to use your word—anchored by her mother and by an object that represents her mother. How does the sleeping scarf simultaneously reaffirm Chino’s independence and ground her bond with her mom?

I’m not sure that I set out thinking, oh, she’s going to come across as independent, but actually she does. That’s important to me. I really believe in the idea of autonomy for children. By that I don’t mean being their friend—I believe in being a parent because I really do think that parents know better when children are [young]. With that said, the idea of encouraging independence while also making it clear that you don’t get to make all the decisions is important to me. The idea that you can explore your world, you’re not being stifled but rather, you’re being guided. I also believe in communication and having conversations. I believe in trying to persuade rather than just telling or demanding a child. I love the idea that Chino comes across as having this kind of independence, running around with her scarf and getting up to things in her day.

What are you working on now, and can you say more about what you’re envisioning for the series centering Chino?

I’m just thinking about the next one right now so I know she’s going to be a bit older. I’m going to base it on my family but I don’t know much more beyond that. Really, at this point, I’m making notes and again, realizing that writing a children’s book is quite difficult. Actually, I’m supposed to be hibernating right now because I’m working on—knock on wood—a novel. That’s what’s been taking up all my time.

What is your writing process like when you’re working on a novel as opposed to a children’s book?

Oh, it’s entirely different. With a children’s book, I’m much more open to the idea of being collaborative. So, I’m asking my editor what she thinks of the lines or asking if maybe it’s too wordy. With my novels, it’s an intense process. I’m a person who works very intensely; I don’t let anybody read drafts until I’m almost happy with them, and I am obsessed with editing. It’s really different also because fiction is a thing that I think of as my vocation; it’s the thing that I deeply love and that, when it’s going well, makes me the happiest. I find that I become utterly absorbed. I don’t want to break the continuous creative world.

Mama’s Sleeping Scarf by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, writing as Nwa Grace-James, illus. by Joelle Avelino. Knopf, $18.99 Sept. 5 ISBN 978-0-593-53557-8