News & Community

Possibly the fastest growing demographic in the nation’s arms race, Black women are finding camaraderie in groups that teach firearms safety and change the narrative around Black gun violence.

Several years ago, Shanea Daniels went shopping. She came home with a few things for her two kids, a Michael Kors purse for herself, and a small black bag containing a new handgun.

Her husband was not pleased.

“I’m the gun lover in my house,” says Daniels, 38, explaining that her grandfather was retired military and her dad a correctional officer.

Guns were a natural part of her upbringing, but until she forced the issue with that purchase, her husband had consistently said “no” to having a gun in the house. With time, he came around to the idea, and now the whole family, including their daughters, aged seven and 13, are committed to safe gun ownership.

Daniels, who lives in Delaware, frequents the Baltimore region as the director of chapters and membership at the Atlanta-based National African American Gun Association (NAAGA).

At NAAGA, she oversees 120-plus chapters (nine in Maryland), each with a unique Queens of Defense group that promotes education and support for female gun owners. The program is as on-trend as Daniels’ designer purse, with women now accounting for 42 percent of all gun ownership. A fifth of that population is Black, making women—specifically African-American women—possibly the fastest growing demographic in the nation’s arms race.

White men are still the largest demographic of gun owners, but while the National Rifle Association did not respond to a request for demographic information on its five million members, it has its own female-forward programs like “Women on Target” clinics, billed as a “safe and friendly environment” where women who are curious about firearms can begin their exploration.

Gun ownership across all demographics rose with the 2016 election and its subsequent social unrest, then spiked during the pandemic. The 2021 National Firearms Survey stated that “about 31.9 percent of U.S. adults, or 81.4 million Americans, own over 415 million firearms,” an average of five guns per person. And the National Shooting Sports Foundation found that 87 percent of firearms dealers reported an increase in Black women buyers in the first half of that same year.

“Since the pandemic, since Donald Trump’s election, and all the things that are happening politically, there has been a rise in African Americans needing to—not just wanting to, needing to—protect themselves, because the racism we believed was dormant in the country….Well, race is now back on the table and we needed to collectively protect ourselves,” says Daniels.

She says that, with high crime rates and the particular vulnerability of women, it’s no wonder female gun ownership is growing.

“Women have been seen for many generations as sitting ducks,” says Daniels. “You have a lot of single moms who are raising multiple kids who are working around the clock…I think women have just decided, ‘I don’t want to be a victim anymore.’ Women have decided enough is enough.”

“I THINK WOMEN HAVE JUST DECIDED, ‘I DON’T WANT TO BE A VICTIM ANYMORE.’ WOMEN HAVE DECIDED ENOUGH IS ENOUGH.”

A brief history lesson, to better understand this trend: While the Second Amendment gives persons the right to bear arms, that right has not been equitably honored throughout the centuries.

An article in the Georgetown Journal of Law and Modern Critical Race Perspectives explains that, “When the Second Amendment was written, there were racist gun laws already in place, restricting the possession of firearms by Black people…Some scholars argue that the Second Amendment itself was included in the Constitution to ensure whites were able to control their Black slaves.”

Philip Smith, NAAGA’s founder and national president, says that new member orientation always includes a bit of history, from the rebellion of enslaved people led by Nathanial “Nat” Turner in 1831 to the Deacons for Defense and Justice, a civil rights militia group in the 1960s that armed itself to protect African-American voters from the Ku Klux Klan.

“It’s been much harder for us to access the Second Amendment and, when we do exercise the Second Amendment, to be respected and taken seriously like our white counterparts,” says Smith, noting that Black gun owners undergo more legal scrutiny than whites when exercising their right to self-defense, for example.

One need only look at the example of U.S. Airman Michael Giles. The veteran fired two shots from a gun he legally owned to defend himself when he was hit in the head during a brawl in a nightclub. The person he shot wasn’t seriously injured, but Giles was convicted of aggravated assault and is serving 25 years in a Florida prison. Or Siwatu-Salama Ra, a Black Muslim woman, who brandished her—licensed and unloaded—gun at a driver who rammed the car her two-year-old child was in. Ra was sentenced to two years.

“I’m not a prejudiced person or someone that likes to make excuses, but that’s just the day-to-day reality that our folks have to deal with,” says Smith. “I wanted an organization that spoke to that, that was a safe space for us to come and just talk about firearms.”

Smith himself grew up the “nerdy” middle kid in a family of five in California, where guns were just not part of the culture. He worked in San Francisco and Silicon Valley before moving to Atlanta, Georgia, where his wife wanted to raise their kids. There, he had two colleagues—one white, one Black—who encouraged him to go to the gun range with them. Eventually, he relented.

“I shot everything they provided for three hours and had the greatest time of my life,” says Smith.

And as he was leaving the range, he thought, “If I, a Black man with no experience with firearms, can have this much fun, I know there’s other Black folks in my community who would love to do this.”

He founded NAAGA in February 2015, during Black History Month. He wanted to start an organization that not only filled a niche for Black gun enthusiasts and focused on training, education, and safety, but one that changed the stereotypes around Blacks and guns.

“When I first started the organization, I went to Google and typed in ‘Black people’ and ‘guns,’” he recalls. “The imagery that came back was crazy—it was all pimps and prostitutes, gangsters, police arrests. Nothing positive.” NAAGA has since flooded social media with images of parents shooting with their kids and groups of women at the gun range, reflecting a more accurate experience.

Smith says NAAGA’s 40,000-plus membership is more than 38-percent female. In his experience, women are open and social and ready to learn.

“Women come in groups four, six, eight deep—they bring their sister, their mom, their girlfriends,” he says with a laugh. Gun manufacturers take note of this, too, as women who do activities together tend to also shop together, translating into more gun sales.

“I foresee, very soon in the future, a time when Black women, or women in general, will outpace men as gun owners,” Smith continues. “Women are getting more of a presence in society; you don’t think twice about a woman CEO, and the same thing is happening in the firearms industry. Women aren’t waiting on a man to buy a gun.”

“I FORESEE, VERY SOON IN THE FUTURE, A TIME WHEN BLACK WOMEN, OR WOMEN IN GENERAL, WILL OUTPACE MEN AS GUN OWNERS.”

The Guntry facility sits in an unassuming brick strip mall in Owings Mills, but the 64,000-square-foot shooting range and training center is like a beautiful country club for gun enthusiasts inside. Even on a quiet Wednesday night in late fall, there are people browsing the retail shop. A young woman pushes a stroller through racks of T-shirts while a father and son peruse displays of rifles and handguns. Several couples check in at the front desk for their range times, as do a handful of solo older men who, given the badges on their gun bags, seem to be retired veterans.

Then there is Dr. Angela Gustus. The 48-year-old Baltimore County resident and her wife co-own a licensed health care organization located not far from the range. She bought her first gun in 2019 and went on to obtain her concealed carry permit (CCW). During the pandemic, when her company was conducting on-site COVID testing, with a lot of strangers and cash circulating in and out, she was glad to have her firearm for protection.

“The missing piece, for me, was having people to go to the range with,” she says.

Gustus joined a local chapter of NAAGA, connected with Daniels, and helped develop a Queens of Defense within that local chapter. The group includes about eight women and is growing. Members made a field trip to a local gun show last year and get together about once a month to have dinner and shoot guns.

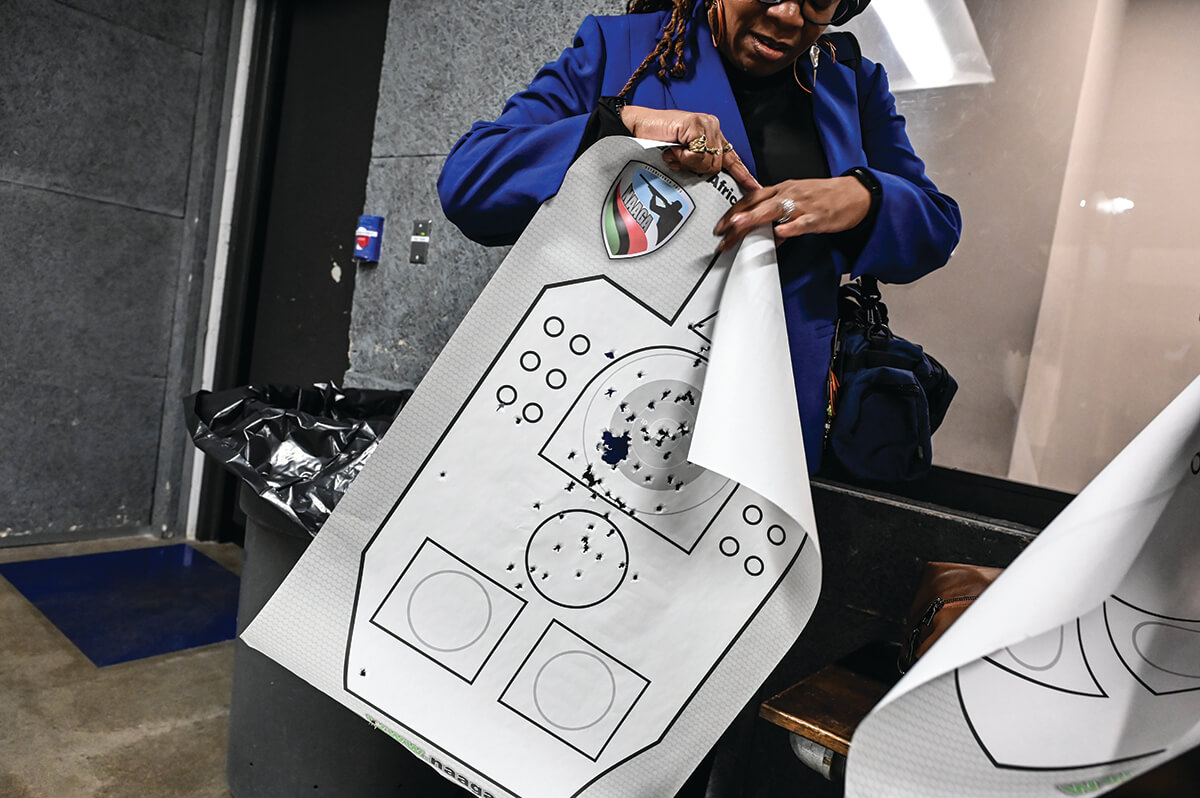

Gustus’ women’s group enters the Guntry shooting lanes in work clothes, scrubs, and yoga pants. Most are middle-aged, although Daniels has brought along her 12-year-old daughter this evening. One by one, they put on their ear protection, unpack their firearms—a revolver, 9-millimeters, .22s, an AR-style rifle—and attach paper targets to a moving arm that is electronically sent “down range.”

Soon, the room is alive with the thunder of guns firing and the ping of brass casings hitting the floor. A friendly staff member pushes the spent ammunition down range with a wide broom like so much hair being swept up at a salon.

“After a rough week, going to the range is my stress reliever,” says Gustus. “When you’re in the booth…you can’t be thinking about anything else, so from that perspective, it’s very therapeutic.”

and Dr. Angela Gustus find the gun range a place not only to train but also to relax and establish friendships.

Gustus says the women’s group takes the intimidation out of going into places where a woman, particularly a Black woman, might feel uncomfortable. But she explains that there are a lot of women who are “closet gun owners.” These women buy a gun but are afraid to carry it or talk about it because of the stigma—that women are meant to be nurturers, not holstering a weapon under their business-casual dress.

On the contrary, Shannon Bromell, an African-American firearms instructor, says women make excellent marksmen because they are more open to training and education than men, whom he says often come in like would-be Dirty Harrys. He began his training operation, Grayman Operators, because there simply weren’t that many African Americans in the Baltimore instructional space. He’s seen that change in recent years.

Bromell, who gave Gustus and others in her group their initial training, says it’s important for all gun owners to get instruction so they learn to be comfortable not only owning their gun, but using it—and knowing when not to use it.

“Whether you decide to carry it or not carry it, whether it’s in your house, your car, on your person, or in your purse,” he says, “go get training so that you are comfortable with the thing that is going to protect you.”

Nicole Pulley, 49, was a closet gun owner. She bought her first and only gun—a revolver—in 2008, on the advice of her father. She was living with her two young children in a neighborhood that he deemed unsafe. For the most part, the gun sat in a case collecting dust. Then the pandemic hit and Pulley’s business—she owned salons in retirement communities—was devastated. She picked up Uber driving but was concerned about mounting carjackings. That’s when her son, now 21, said it was time for his mom to get training as well as her CCW permit. Her son belongs to Bromell’s men’s group and told his mother about the one for women. She finally went, met Gustus, and has since found a community.

“Women should at least know the basics of firearms safety, and it’s a really good hobby,” says Pulley. “Imagine you’ve had a bad day and someone has gotten on your nerves. What better than to go to the range and take it all out on paper?”

Pulley is now a licensed childcare worker. While those close to her know she owns a gun, she understands the need for women to keep their gun ownership in the “closet,” citing pushback, often from other women. “They come with the fear first, all the children getting killed and all that, and my rebuttal is education and proper training prevents curiosity.”

As far as her own personal safety is concerned, Pulley is pragmatic about her gun: “I’d rather have it and not need it than need it and not have it.”

Roughly 72 percent of gun owners say they have it for protection, but not everyone agrees that it is the best way to keep oneself safe. In fact, some studies show having a gun in the house increases one’s likelihood of experiencing violence, with one study stating homicide rates are twice as high in gun-owning households than those without, and that the presence of a gun makes crime more violent.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) calls firearms deaths in the U.S. “a significant and growing public health problem” and notes that “record high levels” of homicide and suicide involving a gun have risen as gun ownership has grown. CDC research shows that from 2019 to 2020, the firearm homicide rate increased about 35 percent and that 2020 was the highest recorded in over 25 years.

Gustus says she sees plenty of opportunity for gun reform in this country, but she’s of the same mind as Pulley. Gustus fell enthusiastically into gun ownership, and now her wife and son are also armed with CCW permits. Seeing the need for more inclusivity in gun instruction, she became a licensed firearms and CCW educator last fall, and now offers classes open to all, but with specific focus on women and LGBTQ+ gun owners.

“I wanted to be able to train people that look like me and have similar lifestyles that I have,” Gustus says. “It’s not that male trainers can’t train women. It’s that some women may not feel comfortable with a male trainer. It’s that some people in the LGBTQ+ community, some people that are trans, may feel like, ‘I don’t know what I’m walking into.’ I want to create a space where people can come in, no matter who they are or who they love, and get trained.”

For all the camaraderie that comes with female gun ownership, there is an underlying reality that increasing gun sales are women’s reaction to feeling unsafe.

“As long as other people can shoot me, I promise you, I want to be able to protect me,” says Gustus.

Black women, in particular, have higher rates of domestic partner violence and are murdered in greater numbers than white women. These women say the answer to that epidemic of violence is self-defense.

“We’ve absolutely seen a group of younger, predominantly female people coming through the doors, saying, ‘Listen, I have to be my own first responder,’” says Daniels.

It might seem contradictory for Black women to champion gun ownership, given the disproportionate impact that gun violence has on Black communities. But NAAGA’s Smith pulls no punches on the topic, saying it’s easy for some to take the high road of reform.

“But I see families living inundated with crime, prostitution, gangs,” he says. “[Our members] are thankful they have the ability to go out and buy a gun to protect themselves.”

Bromell says that if we want to change the narrative, specifically around young Black men and gun violence, it all goes back to access, training, and mentorship. He’s begun a Grayman Young Guns group to improve youth understanding of firearms and safety.

“If you take those same young Black men off the streets and you give them a sense of responsibility when it comes to firearms, a sense of purpose, and a place to train, they go from that gangster with a firearm to a firearm owner with a CCW, and now they have another level of respect for themselves as well.”

Daniels adds that you can’t have a conversation about gun violence without understanding the historical and cultural context of Black gun access in America, or addressing social determents today.

“There is gun violence in Black and brown communities, but there’s also a lack of education, of understanding, of cultural experiences,” she says. “So at the end of the day, it’s how do we provide communities with resources? How do we invest in those communities?”

When asked what she thinks gun ownership will look like in 10 years, Daniels turns to her daughter, who, at 13, is already a capable and confident firearms user. “Honestly, I don’t envision myself carrying a firearm,” her daughter says, “only because in 10 years, I would hope that the world would be safe enough that I won’t need one.”

It’s a good answer, but one that makes her mom “nervous,” especially as global tensions increase, shootings become more commonplace, and a contentious presidential election looms.

So until that just and equitable world manifests, it’s likely women will continue to be at home on the range.