If we build it, will they come?

That’s the question Adrian College president Jeff Docking asked himself when he first arrived at the small liberal arts institution in southern Michigan in 2005. At the time, Adrian’s enrollment was at a near-historic low of about 800 students, and incoming classes were shrinking. The tuition-dependent college was losing millions of dollars a year, and its endowment wasn’t large enough to compensate.

“When I got here, I looked around at this small Midwestern town, the cornfields that people needed to drive by to get to campus, the boarded-up windows on the bulk of the businesses, and I said, ‘I gotta figure out something that will draw kids to this school,’” Docking said.

That something was athletics. During Docking’s tenure, Adrian has added more than 30 new sports teams, from traditional programs with broad appeal, like wrestling and ice hockey—the latter of which won Adrian its first Division III national championship last year—to niche offerings like synchronized ice skating, bass fishing and even varsity cornhole.

The gambit paid off. Enrollment has more than doubled in the past 15 years; Adrian’s latest freshman class alone was nearly 600 students. Docking says about 70 percent of the student body are now athletes.

Docking said Adrian’s success was due in part to his candor about the primary purpose of the new sports programs: to draw new students to campus.

“Every coach knows how many students they need to bring in each year, like a scoreboard in a sporting event. They learn that number pretty much when they’re interviewing for the job,” he said. “We want wins, and we want athletes who are also good students, absolutely. But what we need is bodies.”

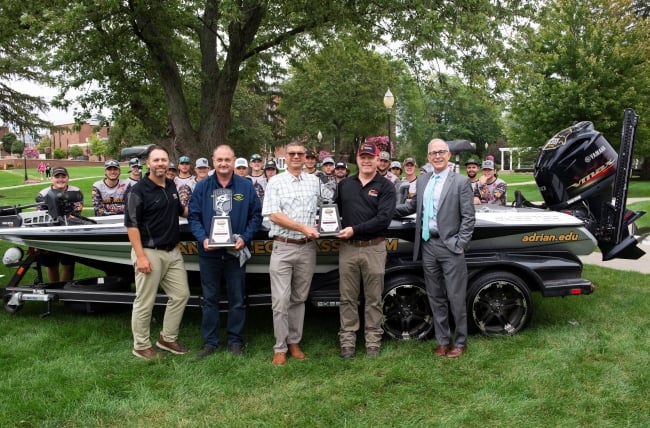

Adrian College president Jeff Docking, far right, stands with coaches and members of the college’s varsity bass fishing team and one of their new fishing boats.

Adrian College

Adrian’s athletics-driven enrollment strategy has grown more common in recent years. The National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics—which, according to its website, “serves the interests of small colleges by driving student-athlete enrollment and financial sustainability”—has added 21 new member institutions in the past three years. From the Rust Belt to the Bible Belt, small private colleges are turning to athletics as a way to attract new applicants—especially male and minority students, whose enrollments are lagging—raise their regional profile and replace dwindling revenue streams.

David Ridpath, a professor of sports business at Ohio University, said the trend has been a rare reliable lifeline for higher ed institutions in an age of increasing precarity. Coaches at small colleges often double as regional recruiters, complete with set quotas that are as vital to their success as their season records.

“With sports teams, you’re bringing in a definite number of students: however many are on your roster, that’s your yield,” he said. “If you’re a Division II or III athletic director or head coach, you’re essentially graded on how you’re helping the school in enrollment.”

But there can be drawbacks to investing heavily in sports, including unexpected changes to campus culture and falling academic standards—such as the drop in average incoming GPA at the New College of Florida, which made up for an exodus of students after Governor Ron DeSantis’s politically charged takeover by spending lavishly on new athletic programs.

“You just have to be careful not to let the athletics tail wag the academic dog,” Ridpath said.

Angels in the End Zone

Calvin University bet big last year on a new NCAA Division III football team, as well as a three-wing athletics complex to house a stadium and facilities for other new teams such as acrobatics and men’s volleyball.

The private Christian university in Grand Rapids, Mich., wasn’t losing students, but it wasn’t growing much, either. Faced with strengthening headwinds, including regional demographic shifts and a shrinking market for small liberal arts institutions, Calvin hired a former University of Oregon offensive analyst as the head football coach, broke ground on the new field and started recruiting players in earnest.

This fall, first-time enrollment grew by 15 percent, from a little over 1,000 students in 2022 to a historic high of 1,150.

Calvin provost Noah Toly said student athletes made up about half of that gain and that the program has already paid for itself. The football team, a 62-man squad that is playing only practice games this year as it prepares for its first season in 2024, drew a crowd of over 3,500 to its inaugural homecoming scrimmage—larger than Calvin’s entire student body.

“It’s a great outcome for us,” Toly said. “It positions us well to recruit more players and nonathletes who just want to come to a college that has football, that has that kind of spirit.”

Steve Ross, executive director of Pennsylvania State University’s Center for the Study of Sports and Society, said that for small colleges that don’t offer athletic scholarships, spending on athletics can yield a “big economic reward,” attracting full-paying students who aren’t quite skilled enough to play big-time college sports but don’t want to give up their passion.

“Without scholarships, the only cost is coaches, some equipment and modest travel,” Ross wrote in an email. “Now a bunch of high school athletes not gifted enough to get an athletic scholarship somewhere can choose: have their affluent parents pay $40-60,000 per year to attend college where they can play basketball, or come to Penn State at $13,000 a year where they would be limited to intramurals? I suspect many will choose the former.”

Wins and Losses

Last year Fontbonne University, a Catholic institution in St. Louis, established its first “sprint football” program—a version of traditional football that’s faster, since it does not permit players over 178 pounds. The university recruited 45 students from across the country, offering competitive scholarships and hiring coaching staff.

“Football is one of those sports that, because of the size of the roster, can really help with enrollment and bringing in tuition revenue,” said Fontbonne president Nancy Blattner. “Track is like that, too. But there’s something about the rush of football that also invigorates the campus.”

The new enrollees helped narrow the gender and racial gaps on campus. Fontbonne was founded as a women’s college, and its student body runs about 60 percent female. But this fall, for the first time in its century-long history, male enrollees outnumbered women—a shift Blattner attributes to the football team. In addition, nonwhite enrollment at the predominantly white institution rose by 10 percent.

Ridpath said that diversity will likely become an even bigger driver of the growth in small college athletics in the wake of the Supreme Court’s affirmative action ban.

“I’ve always been uncomfortable with the rationale for athletics ‘giving’ students of color the opportunity to go to college, which plays into dangerous stereotypes,” he said. “But schools are looking for a back door to diversity now, and sports are certainly one way to do that.”

A running back for Fontbonne University’s sprint football team, which played its second season this fall.

Fontbonne University

Sometimes new athletics programs give rise to unexpected hurdles: at Fontbonne, for instance, nearly half the football squad failed their classes after the first season.

Blattner said Fontbonne’s retention rate was actually better than the 38 percent average for the other seven teams in the two-year-old Midwest Sprint Football League, adding that the university offered scholarships but did not lower its academic standards for players. Still, the fact remained that the investment had drawn students—but not necessarily those who could balance academics with athletics.

Blattner said she hopes the players, current and future, grow to understand their academic commitment in addition to their athletic responsibilities.

“I went to speak to the team early this week, and I was frank with them,” she said. “I said, ‘None of you are going to play for the Chiefs, but you can get a four-year degree that will change your life.’”

Steve Rackley, a professor of sports management at Rice University, worries about liberal arts colleges losing their own identity in the pursuit of athletics-driven enrollment gains.

Rackley spent 20 years as an athletic director for two private liberal arts colleges: first at the University of Findlay in Ohio, and then at Alma College in Michigan, which he left in 2019. At both institutions he said he was required to give his coaches enrollment goals, and he felt pressure to keep adding programs to draw new students. Both eventually offered more programs than many D-I institutions.

“I really think it can be unhealthy to have too many student athletes on campus, where the ratio is so far out of whack,” he said. “What are we doing here? Playing sports or getting a degree?”

Focusing too much on athletics can lead to a kind of mission erosion, he said, changing a learning community into a sporting one. He saw that at both Findlay and Alma and said he regrets the changes they underwent.

“Is it so important to keep the school open when to do that it has to become something else entirely?” he said. “Is that really what higher education is about?”