One time they walk arm in arm around a European capital.

Another time they drink cognac, visit museums and sing together.

The last time Patrick, Kent and Pelle get into a taxi.

Patrick is sitting alone in a loud breakfast canteen. It is 1 June 2022. It is 15 minutes until his life will change; 16 months until it will end. The early summer morning in Ljubljana is hot. The City Hotel is central and the price decent but that’s not the reason the 59-year-old has booked a room there – he just wants to be around other Swedes.

That’s what the dedicated fans of the Swedish national team do. At home they don’t really communicate with each other. They don’t normally have each other’s phone numbers or addresses, they don’t send messages on birthdays or other special days, and they don’t know if the others are married or what hobbies they have. They support AIK or Trelleborg, they vote for the Christian Democrats or the Green Party and work as carpenters or lawyers.

But as soon as Sweden play away they get together. They share information about which hotel they are staying in and meet in the corridors and greet each other in the elevators. They spend time together in the hotel lobby and the person who goes to the bar buys a round of drinks for everyone.

This particular morning some travel-weary fans amble up to the buffet, getting scrambled eggs and coffee, and sit down at the tables, four by four. Lisen is leaning on a crutch as she enters the room. The knee is hurting. She sees a free chair next to a couple of older men, moves gingerly there and says hello, but notices a man on his own across the room. It is the person she talked to at an Irish pub last night, the Swede who lives in Switzerland these days. What was his name?

Yes, that’s it! “Patrick, do you not want to come over here? There is a free chair for you.”

Patrick walks over hesitantly. He is offered the last place at the table despite the fact that the woman who has called him over has just had an operation. He says hi to Kent and Pelle. “Good morning, it’s going to be a tough game tomorrow. Are you nervous already?” Patrick fits in straight away. Lisen, making her way to another table, notices that he seems as understated and quietly funny as the others.

The next day Emil Forsberg makes it 1-0 with a penalty against Slovenia in the Nations League before Dejan Kulusevski forces the ball into the roof of the net. 2-0. “The old-man gang” are in the middle of the away fans. Their singing is a bit quieter than the others’, sometimes it even looks as if they are miming, but those who know all the faces notice a new person among the group. Next to Kent and Pelle is Patrick. A new friendship has been formed.

At the next away game having breakfast on their own is no longer an option. Kent, Pelle and Patrick have become inseparable. They are interested in culture and visit museums but also like to have quiet downtime, gubbmys, over some grappa.

How did Pelle meet Kent, by the way? They ended up sharing a room on an away trip a long time ago. And Lisen? No one remembers. One day she was just sitting next to the others and they have belonged together ever since.

Patrick, Kent and Pelle are seen as a unit, a harmless, white-haired gang. In Tallinn they philosophise. Giggle. A beer here, a coffee there, a strong drink on the side. One time they go arm in arm with Lisen through central Lisbon, like a group of old sailors.

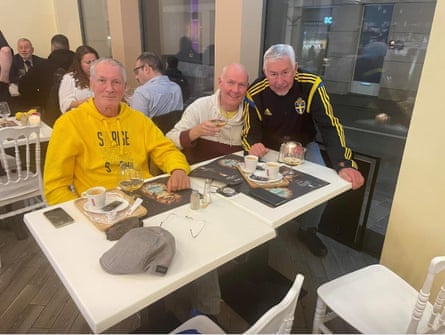

On an autumnal Saturday in Brussels in 2023 they order double espressos and cognac. In two days Sweden will play Belgium in a Euro 2024 qualifier that has almost no significance. The team have not played well enough. The Euros are a distant dream, so only those who believe football is about more than just the points on offer are travelling. Patrick, Kent and Pelle are among those who are there. They want to support Janne Andersson’s squad until the end, sing during the warm-up and show their loyalty.

And they want to spend time together. Sit the way they are sitting right now, on white wooden chairs, together. Patrick hands his mobile to someone and asks them to take a picture. On Facebook he posts a message saying: “Meeting up with ‘old’ friends before the Sweden game. Thanks to Lisen who brought us together.”

Two pairs of glasses are in front of them. Kent is wearing a yellow hoodie. Pelle has gone over to their side and is leaning in next to Patrick, who raises a glass to the person taking the photo. That night they have dinner together. On the Sunday they do touristy things and on the Monday they are getting ready for the game. Just before seven o’clock in the evening they stop a taxi and ask the driver to take them to the stadium.

The journey goes through Brussels in the dusk. The sun has just gone down behind the art nouveau houses and the passersby are doing up their jackets against the cold. The taxi turns towards the canal.

The three passengers have seen many stadiums and stands in their lives but they won’t get to the King Baudouin Stadium. Five kilometres from the stadium a moped stops and the driver, in an orange reflective vest, gets off and opens fire towards them.

The rain of bullets kills Patrick and Kent. Pelle is hit too but survives and is taken to hospital. The game between Belgium and Sweden starts but is abandoned at half-time. The next morning the terrorist is shot dead by police.

The terror attack affects politics, national safety and sport. It evokes sadness, anger and fear. But when friends and relatives of the victims read the papers the following week it feels as if one ingredient is missing. Where is the warmth? Why does the reporting about three gentle friends feel so emotionless? Is there not room, even in these times of terror, to tell a story of love, for each other and for football?

There is, and Lisen Altis is the best person to tell it. Back home in Sollentuna, outside Stockholm, she works at an insurance company, but before Sweden men’s games her personality changes. She becomes more outgoing, happier and even more caring about other people’s wellbeing. Before Sweden’s games she doesn’t just join the nationwide supporter club Camp Sweden, she infuses energy, humour and kindness into it.

“They used to call me ‘The Queen of Camp Sweden’,” says Lisen when I speak to her on the phone. Since she lost her friends her brain has been a mess, she says. She warns me that she cries one moment, then babbles on the next before going silent. Despite all of this she is OK to meet at our newspaper offices. “I have to, because it is my boys. My old-man gang. Everyone has to understand who they were and what nice people they were.”

So we meet. Lisen drinks black coffee and tries to remember. She gesticulates wildly and screws up her face to keep the tears away. She phones a supporter to fill in a detail, then another one, and another one. According to Lisen the Sweden football family is relieved that a piece is being written and wants to contribute with information. A lot of them, though, are finding it too painful to give interviews.

“As soon as I got to a new city it was the guys I was looking for,” Lisen says. “You weren’t in contact between the games but then they would still just appear and give me bear hugs. I had two families, one at home and the other out on my travels. Kent, Pelle and Patrick were my older brothers.”

The three men talked in a similar way, were equally generous, and they were personalities. “Kent used to have this really ugly felt hat on his head. It had horns and was full of pins from old games. He was the calmest of them, didn’t talk that much.”

Pelle was the joker, says Lisen. “He was so happy to see us. ‘Ahhh, there you are,’ he would say in a high-pitch voice. ‘I’ve missed you!’ He was never sexist or coarse but he would fire off these jibes, full of love. A twinkle in his eye. You’d sit down next to him and a beer would appear straight away. And Patrick …”

Lisen breaks down and pauses to look through old pictures and tries to find the right words. “He was the one who was most interested in football of the three,” she says. “He had coached a lot of girls’ teams but was a bit of a ground hopper now, someone who would travel to look at stadiums. And it was enough to talk to him for just a little bit to realise how kind he was. Through and through nice.”

Lisen isn’t averse to wearing her own bad headgear. One favourite was a wreath with plastic yellow and blue flowers. When she visited the memorial at Sweden’s national stadium, Friends Arena, she put it down. “I made it into a heart shape. My boys deserve that.”

Pelle returned to Sweden after nine days in a Belgian hospital. He has a superficial head injury from bullet fragments that has had an effect on one of his arms but he hopes to get his movement back with physiotherapy. Kent and Patrick have had their funerals.

Lisen doesn’t know how to channel her feelings. She wants to talk, despite the pain it brings, and she needs to share her darkest thoughts. “After it happened I felt guilty about it,” she says. “It felt as if it was all my fault. If only I hadn’t been some bloody facilitator. Everyone tells me not to think like that and that I can’t rewind the tape anyway. So I try to remember something else. Because the boys were so happy together. They were bloody happy.”

The four were very similar. Their love for football was like a massive fire but of the sort that young smarty pants rarely understood, because it wasn’t reliant on formations or group tables. They loved the national team. They loved each other, the whole group of travelling enthusiasts. They loved to land in a foreign city, to see a yellow-and-blue-clad person and banter with them, to march together on a matchday. “One of them would always leave the march and run into a shop,” Lisen says. “Who is having a beer or a cola? Then he would come out and hand it out, without caring about who is paying for what.”

Everything has been broken now. A vase has been thrown to the ground and the pieces will never be put together again. All over Sweden there are people who have toasted and joked with them, men and women who at the next game will look out over the gathered fans but realise that there is an ugly felt hat missing.

This is an edited extract from an article published in Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet in October 2023