An Interview with Yaraan Couzens-Bundle

Tell us about you, your mob, and the land and sea country for which you speak.

My name is Yaraan Couzens Bundle and I’m a proud Gunditjmara, Yuin, and Bidjara woman. I’m a whale dreaming custodian on my Gunditjmara bloodline.

My old people have been here since time immemorial. We have this concept called deep time, and we’ve been here since the first creation. I’m sitting on Koornkopanoot-speaking country in Warrnambool. I’m the proud founder of SOPEC, Southern Ocean Protection Embassy and Collective.

My family and bloodline are directly connected to Koontapul, our word for Southern Right Whale. She is the oldest storyteller in the world and connected to the oldest creation stories that come from our Country

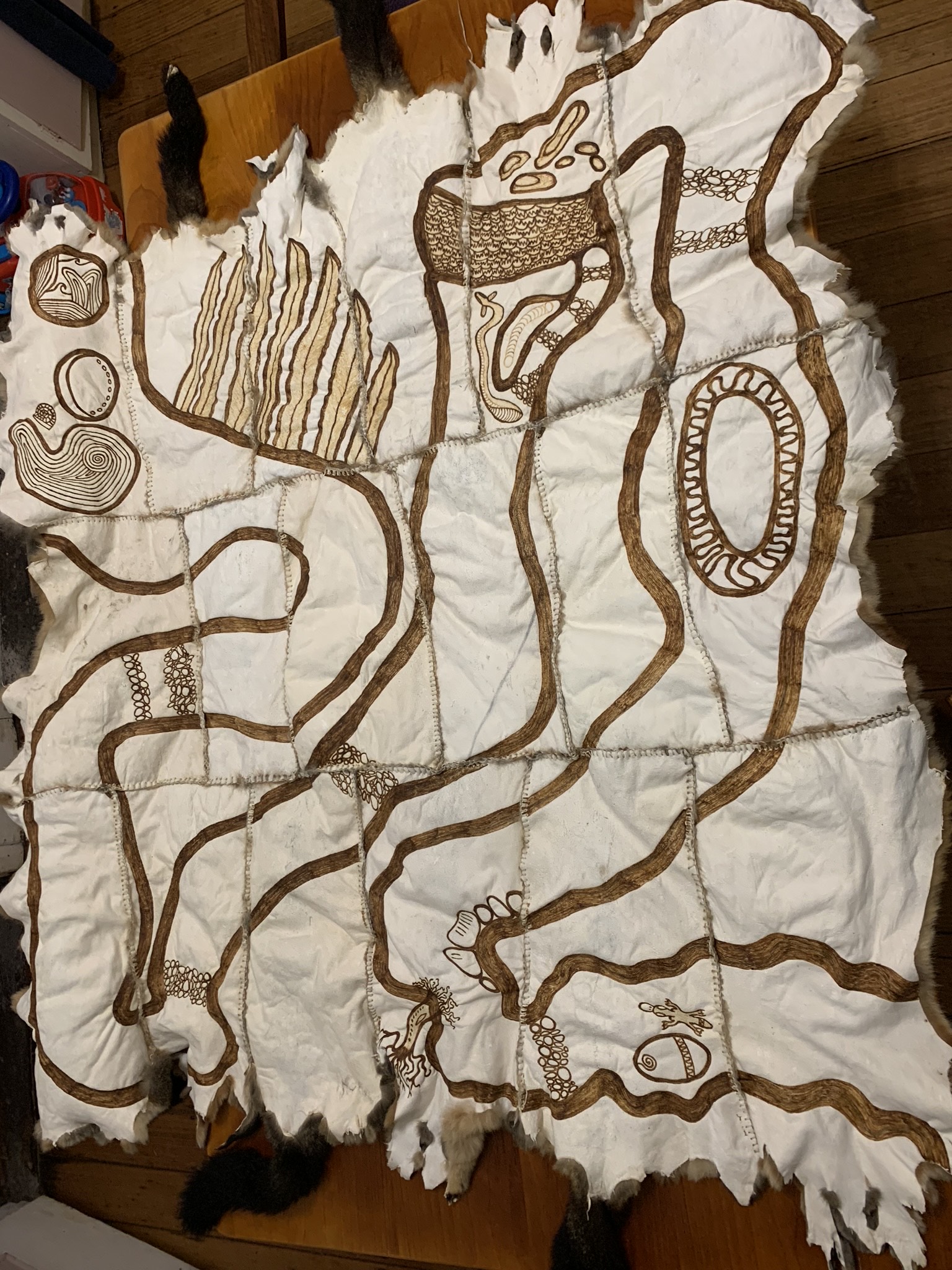

The country makes up the shape of the Koontabpul’s body – the story on country – so that the head of the whale down through the blowhole, and the body, and the fins, and the tail, and the whole body of Koontapul is what is shown along our Country. It extends from our spirit into our physical and spiritual body. And all that belongs to our matrilineal country.

The purpose of having those kinships is to maintain the sacred balance of our place of belonging on Country. That means to be a custodian of these sacred stories is absolutely phenomenal in my eyes. Every day, I am in such deep gratitude of how clever my old people were, and are, and how we are built, were born to carry this on.

It is a great honour and privilege to be able to be a custodian of the whale dreaming the Koontapul yakeenij, and that’s our word for whale dreaming, and all the other kinship relationships that we have to our country. The relationship was always reciprocal – we’ll never take from Country without giving back to it.

The sea sustained my people for aeons. We owe the bounty of our people and the rich amount of food and resources that we were able to have and maintain, and give back to that sea country. So that extends from the Koontapul yakeenij, on the Gunditjmara side.

One of those jobs in particular is that the Koontapul, as part of our Women’s Business – they are our midwives, and we are theirs. It goes beyond just being a food source.

Another example of our connection to sea country is on my father’s side. So my mother’s side is Gunditjmara, and on my father’s side is Yuin from the south coast of so-called New South Wales. Our connection was with the dolphins. My uncles and my grandfathers used to call in the dolphins and they would have a kinship, family connection of hunting together so the dolphins would herd the fish in for the fishermen and every one would get a feed.

Another really sacred connection is the story of the orcas, the killer whales. My grandfathers and my uncles used to hunt the baleen whales with the orca family. They would go out to sea on the signal of the orca coming up to the headland breaching out of the water, singing out to the old fellas there. The old fellas would jump in their long boats, their canoes, and go out and follow these orcas. The orcas would do the herding of the baleen whales in close enough for the whalers to get them. Then there was the law of the tongue, which the orcas had to have the first feed and they would usually take the tongue and sometimes the liver. Then the rest would be given to the humans, and [the orcas] would swim with the boat and the whale carcass back into the bay. Then it would all happen again next time when they were hunting whales.

So that story is part of how the Eden whaling station and industry was built, and also how it was finished. A lot of people don’t know why it was finished, they just think the orcas passed on. One of the stories I got told was that the old people were doing ceremony with the orcas in a smaller, quieter bay. They were being spied on by the Ngamatitj, that’s our Gunditjmara word for whitefellas. And one of the whitefellas came up, and seeing that the grandmother and the orcas were still in the bay when the mob moved off, he rowed out in his rowboat, and he shot the grandmother and killed her. Then after that, there was no more orcas, and that relationship was gone, and the orcas left. The whale industry crashed after that in that area. So yeah, it just shows the greed of the Ngamatitj, and the continuation of that greed is the same greed and poison that we’re fighting on sea country today.

When colonialism started to impact your lands, what were the main waves of dispossession and violence?

Gunditjmara country and so called Victoria have their own invasion day. It wasn’t just Botany Bay, and Cook the murderer. It was also the Henty family, the mass murderers. They came up from Tasmania, and they landed in the Portland Bay in 1834. They’ve still got their plaques today, which on the anniversary of that invasion day, we go and cover in ochre and our handprints, and tell them that we’re still here. The same blood that they tried to destroy is the same blood flow flowing through us now. They tried to massacre all of us. One of the largest known recorded massacre sites in so called Victoria is the Convincing Ground.

Part of the story of my old people is that a war was started over a whale carcass. The mob came in to do ceremony and several clans gathered there, and others from all the way up into what we know as the Volcanic Plains area. And the whitefellas come in and tried to claim that whale, and ended up massacring men, women and children in the hundreds.

My people were shot in cold blooded murder for homesteads to be established, and our villages destroyed and pushed into piles of rocks, and sheep farms and pastures established. That happened all over Gunditjmara country and up into Tjapwurrung country, which is where I also belong to.

If you look on the national massacre map, you’ll see that basically, our whole country is covered in red dots. That includes our connection to our sacred Burnang (Dingo) – the apex predator on the land, and that interconnectedness to the water. To this day they can’t shoot us anymore, but they still shoot and kill the dingoes. The genocide is still happening to our people and our country at a really high rate.

Can you speak a bit to how this has impacted your women, particularly?

Just to speak to this subject briefly because it’s so emotional, the hurt is really raw. I think that it definitely needs to be mentioned that our old, clever women, the women I come from, they prepared seven generations ahead. So they knew what was happening in the time of colonisation. They took that women’s business into their physical bodies and their spiritual bodies, but they also hid clues for us in the country, for the future generations to find. Because they knew of the violence that was being perpetrated on to all of us, and black women in particular.

There’s a whole new generation of Gunditjmara youngbloods that are recognising their strength and the love and, and powerful gifts that our old people left us in our blood, and that it wasn’t just the intergenerational trauma. It was intergenerational love and connection for our country and our responsibilities, which it isn’t hard when you do it properly.

Why and how did you create SOPEC, the Southern Ocean Protection Embassy?

I’m a saltwater and a freshwater defender. Our freshwater is intrinsically connected and linked to the serpent, the Rainbow Serpent dreaming, and it’s very, very sacred. You know, water is all life, basically. So, I created the Southern Ocean Protection Embassy as a last stand for Sea Country. That collective is open to mob and anyone who wants to join and walk alongside us in our fight for Country. It was created in defence of the whale songline, and in fact, defence of our whole sea country. We’re reestablishing our place of belonging when it comes to cultural Law way.

It’s a beautiful revival story as well – where those teachers aren’t always there to teach us in person, Country speaks and the sea country speaks very strongly to my blood, and it’s one of the deep connections that I have to Gunditjmara country and, and one of the oldest coastlines in the world. The saltwater and the freshwater, they’re their own living entities, they’re alive, they breathe – you know, the waves going in and out and the tides and the swells, that’s the ocean breathing. And it’s literally the blue lung of our planet.

So when I learned about the seismic blasting and all the industrialization that they want to do to our sea country, I thought, ‘Hold on a minute, I need to do something about this, I need to make sure that the languages of the ocean are protected into the future.’ “They” being the gas companies, and the state and federal governments who get royalties from the gas companies (who don’t actually pay tax), and are there to make massive profits.

I’m a language defender as well. So I hold that very close to my heart – what languages are being saved, and how I’m learning to speak them again, and share them and teach them into community. And the vibrations of what those language words are saying, and the meaning of those; the frequencies from your heart centre, the vibrations of the sounds, they belong to country, and they’ve belonged to country for thousands of years. This is our cultural heritage that needs to be treated with the utmost respect and protection, and be protected into the future.

These huge companies, international companies want to seismic blast 55,000 hectares of sea country. And it covers almost the most of the length of Gunditjmara sea country. There’s another one that wants to blast,only three kilometres offshore, off Port Fairy and Warrnambool and Portland area. And, again, that’s too close to our sacred burial Island, Deen Maar. These companies, they’re not welcome. The wind farms, to get their permanent infrastructure into the sea bed, they have to seismic blast to provide a picture of where this is going to go, in 45 metre-deep blue whale feeding ground. From the little tiny zooplankton, all the way up to the largest creature in the ocean, the blue whale, and everything in between, is at risk of major damage, and destruction, extinction.

The seismic blasting has a direct devastating impact to all sonar animals in the ocean. What it does is they misnavigate. It can actually haemorrhage and destroy their whole hearing and it can make them really vulnerable to predators. And, you know, newborn and young whales, evading predators because they can’t hear their mum.

It’s been said that the mothers use the shallow bays for resting and protection. They whisper to their children when the predators are going past. They have this amazing oceanic language that a lot of the world is still discovering, but that my people have held for thousands of years.

It’s taking away their home, their physical body and their languages. And it’s just mass ecocide.

I fully believe there is a way forward for wind and wave power, even sun power. There’s other ways that we can avert the climate crisis, and find those solutions to move forward. An example of that is seaweed farming, providing more forests in the oceans. In fact, the whale’s job in the ocean is helping to provide more oxygen for the rest of the world.

NOPSEMA is supposedly a Commonwealth independent Statutory Body that oversees safety for oil and gas explorations and operations in waters claimed by the colony of Australia. Have they failed in their job?

NOPSEMA have failed the First Nations mob and the wider Australian community, because I believe they’re in league with these gas companies on a much higher level.

I believe that the community consult person for one of these companies used to work for NOPSEMA. That says more than a thousand words. Another example is they’ve just approved the TGS & Schlumberger Environmental Plan for the 55,000 hectares they want for seismic blasting. This company] is under investigation, because they’ve gotten called out for blasting in areas they weren’t fully approved for. That’s just so corrupt. Now they want to up the ante from 2D to 3D seismic testing; be approved for one part, and under investigation for the other part. I don’t think that investigation is finished. Their environmental plan is what we’re trying to challenge at the moment.

NOPSEMA are actually the greatest liars and thieves, because they’re saying that they can minimise the damage through their environmental plan – but their (approval of) environmental plans can’t possibly understand the full extent of what they’re damaging, because they don’t know. Not enough research has been done to the species in the Southern Ocean. And so if they don’t know about those species, how are they going to manage not making them extinct?

What was the consultation process like?

When they first came to our country, we found out about it through an organisation called the Otway Climate Emergency Action Network. They only originally initiated consultations with the fishing industry, they tried to bypass us completely. And we found out about it and said, “Hold on a minute, we’re the main relevant people that you need to be speaking to and consulting with.” But consulting is not consent.

We want to make clear that we say absolutely no to all of the proposals, every single last one of them.

You’ve also been part of other campaigns and fights, like the Djap Wurrung birthing trees, and a basalt quarry on Gunditjmara Country. As a blak woman, what did resistance look like for you?

The Djab Wurrung birthing trees…. that was really full on, being on the frontline – living on the frontline at camp with my older daughter who was a baby then. She’s now five, and she was almost one at the time. So I actually got the honour and privilege to be breastfeeding her in a sacred women’s site, and to be able to reestablish our permanent ceremony ground. We lost in that fight. My countrymen and countrywomen were criminalised for defending country. Some of them even got locked up over it.

One of those trees actually even unfortunately got cut down, the Directions Tree. So my daughter Yaani and I went and collected the seeds for that tree. We still have some of the seeds, we’re planning to have a big community gathering – one for mob and one for everyone – that we can go back to Djab Wurrung country and plant these seeds of this rare yellow box that was cut down. Rejuvenate and help heal some of the loss that we experienced there.

Another Gunditjmara sister girl, came to stay and live at the camp with her children as well. Both her and I went up to the sacred mother mountain that overlooks this part of women’s country. It’s less than a few kilometres away from the birthing trees. We collected some sacred stones from that mother mountain, and we took them back to camp and we built ceremony ground, which still stands today.

I’m proud to say, after Vicpol and Dan Andrews government removed us and Major Road Projects removed all the people and all the connections, those allies that were supporting us were a global family. So once they were all removed from that place physically, the spiritual fight continued on for us who belong to that part of Country, and our bloodlines belong to Djab Wurrung country. That was a powerful stance that us women could basically say, ‘No way, we’re still here. And you actually haven’t removed us because we are embodied in that ceremony ground, that stone circle. Country is part of us, and we are part of country.’

So they actually didn’t win, you know, and we’re still continuing that fight to this day. We’re still trying to assert those birthrights to the state government and major roads projects about who we are, where we come from, and why us women, in particular, need to be listened to about the sacredness of our country – and what’s at stake if all of that is destroyed.

One of other fights that I was part of, was against the basalt quarry on the Hopkins river out near what’s known as Framlingham Aboriginal Mission. We have our own cemetery out there where my family have the Couzens burial plot, each family’s within their own little place there. So defending literally defending the bones of our old people against these greedy farmers that wanted to go from farming to basalt mining. That case went to VCAT [Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal]. And we recently lost in VCAT, and VCAT said that the quarry can go ahead with restrictions in the cultural heritage management plan. All I want to say to that, is that the cultural heritage legislation is perpetrating violence to our people. It wasn’t written by a cultural law person. It was written by whitefellas, so it was made to manage the destruction of our cultural heritage not to protect it. That’s what I believe and that there’s a lot for the whitefella law that needs to be accountable. It’s another way, another tool, they use to oppress us.

There will be more resistance from Gunditjmara custodians and family groups before they start blowing up – I think it’s the size of three MCGs they want to do. Where they want to do this is on the edge of the Hopkins River – around that part of Country we call Poonoong-Poornoong, and it’s one of our sacred songlines. The headwaters, the birthplace of that river, is actually up on Djab Wurrung country, and then flows down into Gunditjmara Country and comes out down into the Southern Ocean. So it’s a very sacred river and songline place for us.

There’s a whole cave system that my grandfather told me about. The last quarry, only a few kilometres from where they want to do this, is part of that cave network system that runs through there. Another special kinship fella we connect with is the bentwing bat, and they frequent these caves, and they only belong in this part of the country. These little micro bats. They live on a higher frequency, same as the whales.

They just don’t know what they’re destroying. It’s major damage, having these detrimental ripple effects that go not only through us and our physical bodies, but from the past into the younger generations as well.

So it’s really, really disgusting, actually, that we have to defend so many places, and so many sacred places when we have this amazing knowledge and technology today. But they still ignore our local knowledge that could prevent all of this.

How can settler-colonisers/greenies support you mob? What are the steps they need to take to de-colonise?

Recently, I had one of my ally friends offer me support as a single mom to help care for my kids while I’m fighting for country. They said, “you know, we can’t do it without you, sis”. And I really felt that, I was like, yes, solid. Thank you. I’ll take you up on that offer one day. I don’t think she understood exactly what she was saying, because it is one of our precious cultural values that we care for family – no one gets left behind. So I think by her offering that it was a really beautiful gesture, and I appreciated it so much.

On another level, we need them [allies] to basically amplify our voices and our stories, not culturally appropriate [the stories] for their own agenda, or their own way of fighting to protect whatever they want. I think they have to actually put their hearts in the fight like we do.

How does that look, locally?

I think they can go a bit more beyond the surface and find out the local language and people and nations and connections, and educate themselves on the true history of this ancient land. You know, our cultural identity and what we stand for and why we’re saying, land rights and land rights now. Because our old people have been saying that for a long, long time.

I think another way is that campaigns cost money, in this day and age, unfortunately. And we need to be supported through all their different resources and the reach that their connections have, in our fight for Country. Yeah, pay the rent literally.

Yeah, and I just think they need to come and sit with the aunties because the aunties will just tell you straight out. I think we have every right to say, you know, pull up. And learn to listen and come with your heartbeat, not your ego.

Given all that’s been lost, with all that’s still thriving – how can you repair the damage to Country?

It’s a good question. I used to want to be a marine biologist and find out as much as I could about the blue lung of our planet. But I think some of the damage done is irreparable. And a lot of the damage can be healed without human interference. Nature knows exactly what to do.

But also, we sing it. You know, we sing it back to life. And no other mob can do that. We all have a place of belonging to the countries that we have custodial responsibilities for. Last year when the ceremony was happening, the whale ceremony that I was leading and participating in, other locals and other mob were saying ‘Wow, what a bumper whale season we have this this year, you know!’, and I was saying ‘Yeah, that’s because the song is strong again!’ We’re singing and there was more of our mob that joined in that ceremony that year. There were so many babies last year, and it was amazing.

The whales need to hear and reconnect with our song rather than this seismic blasting that’s pushing them away from these sacred places that their grandmother lines of their kin have come to for thousands of years. I think that’s a huge way that we can honour that growth and healing again, singing it back to life. But also, there’s other little, or not little but different, ways that we could support that with proper sustainable eco-tourism. And seaweed farming.

What would justice for Country look like for you?

I think it would come in a few different ways. Like I’ve mentioned, just get out of our sacred sites.

I think education is a huge part of that restorative justice. I think that all of our knowledge systems, you know, what we have left, what colonisation hasn’t suppressed, hidden and destroyed – we should honour that knowledge as the oldest living culture in the world. Surely there’s so much wisdom for everyone else to learn, and honour and mostly respect in how that could help heal the earth. We say Country is priceless, but maybe they could put their resources and energy into education and really supporting a black university level of sharing our knowledge systems.

I also just think if we keep having these yarns, and keep supporting each other, there’s always powerful magic in that. In the strength of who we are and the strength of our blood It’s not just about intergenerational trauma – it’s this intergenerational love. The love in our blood, and the power in our blood from our old people. Those gifts that we were born with, we don’t have to search for. There is enough, and I think if we all come together and utilise that strength magic will happen. There’s nothing in my eyes that can break that kind of powerful magic because they tried to kill us all but here we still stand, here we still are.

Do you have a final message you’d like to share?

I have this message for all the governments and corporations – “we will keep coming. We will keep coming like the waves of the ocean.”

I just think, for our mob too – come and take your place! Everyone has a place of belonging.

And, nyaki, which is look or watch, and wangki, listen now. Use your senses into the future. I think there’s not enough people that are honouring their full capacity as human beings. Come with your tumtumpe, your heartbeat, and nyaki mangaki, use your senses.

Get involved with SOPEC (Southern Ocean Protection Embassy Collective) via Facebook, Insta (@s.o.p.e.c), or www.drillwatch.org.au

To hear the extended interview with Yaraan as a podcast, go to foe.org.au/cr146.