Appreciating art or artists who offend can complicate the idea of cancel culture, especially when others use that as a weapon against your personal values.

By Ruth Etiesit Samuel | Published Nov. 7, 2023

This story is a part of our weeklong series on cancel culture.

Read the other stories here.

“Wait, they were accused of doing what?”

Few things compare to the sharp pang of betrayal after learning questionable information about your favorite musician, actor or athlete. The initial shock, denial and confusion sends fans careening down a rabbit hole, googling to find credible sources to confirm the allegations.

Once the explosive claims are substantiated, feelings of disappointment and hurt quickly surface, then guilt for your own naivete. What’s next? Do you solemnly swear to never support their art again? Erase their songs from your music library? Delete their films from your Letterboxd account? Publicly renounce your support of them with one final TikTok fan cam?

Or, do you reserve a special spot for them as your “problematic fave,” rationalizing your neglect of their poor behavior? A problematic fave could be any celebrity, public figure or fictional character that you continue to hold dear, in spite of their ethically or morally questionable stances, actions or accusations leveled against them.

Ariana Grande has earned two Grammys, despite the donut-licking incident that shocked America. Beyoncé’s “Renaissance World Tour” has become the highest-grossing tour by a female artist, despite that blood diamond collaboration following her Afro-pop soundtrack album, “The Gift.” Taylor Swift’s concert movie broke an opening weekend record, despite her romantic fling with an alleged racist earlier this year.

Gina Rodriguez will continue to be a working actor on Season 2 of ABC’s “Not Dead Yet,” despite rapping the n-word in a widely circulated video. Consumers still bought Yeezy slides and listened to “Ye” after Kanye West said 400 years of slavery was a choice. Shonda Rhimes’ “Scandal” and Dan Harmon’s “Community” are still regularly streamed series with strong fandoms, despite the presence of alleged abuser Columbus Short and the “horrific” Chevy Chase.

Whether systemic or interpersonal, each of these “strikes” against celebs enact varying degrees of harm, yet none of these artists have been barred from work or the public eye. In its distorted form, cancel culture does not really exist for celebrities and public figures. Moreover, every single celebrity, show or piece of media has some stain or impurity. Truth be told, all of our faves are probably problematic, so what does that make us?

At first glance, the notion of a “problematic fave” may seem like an excuse to overlook celebrities’ actions or the implications of a piece of media (i.e., film, TV show, etc.) simply because of your own personal reasons: nostalgia, attraction, or plain enjoyment of their product. In extreme cases of fandom, “stans” — a word formed by combining the words “stalkers” and “fans” — will doggedly campaign for the innocence and sovereignty of their chosen fave.

But below the surface, the “problematic fave” moniker can be a fan’s attempt to hold space for nuance, dually acknowledging a public figure’s legacy of talent and the potential to harm. Recognizing human fallibility and the unrealistic expectation of moral purity from celebrities could be seen as a more mature approach to engaging with entertainment. No one is perfect, and everybody makes mistakes.

However, the standards for what offenses constitute as too egregious to overlook vary from individual to individual. To one person, domestic violence allegations could be seen as worse than fatphobic or colorist comments; to another, they each perpetuate systemic violence in different ways.

These conversations raise questions about the ways we appreciate art: When did the media we consume become emblematic of who we are, or has it always been? Is it reasonable to tether your own morality to entertainment, and what does it suggest about your values? How does having a problematic fave complicate the concept of cancel culture?

The evolution of a problematic fave

The term “problematic fave” originated from a then-anonymous Tumblr blog by the same name, “Your Fave Is Problematic.” Boasting over 50,000 followers at its peak, the blog was created in 2013 and “contained long lists of celebrities’ regrettable (racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, ethnophobic, ableist and so on) statements and actions.”

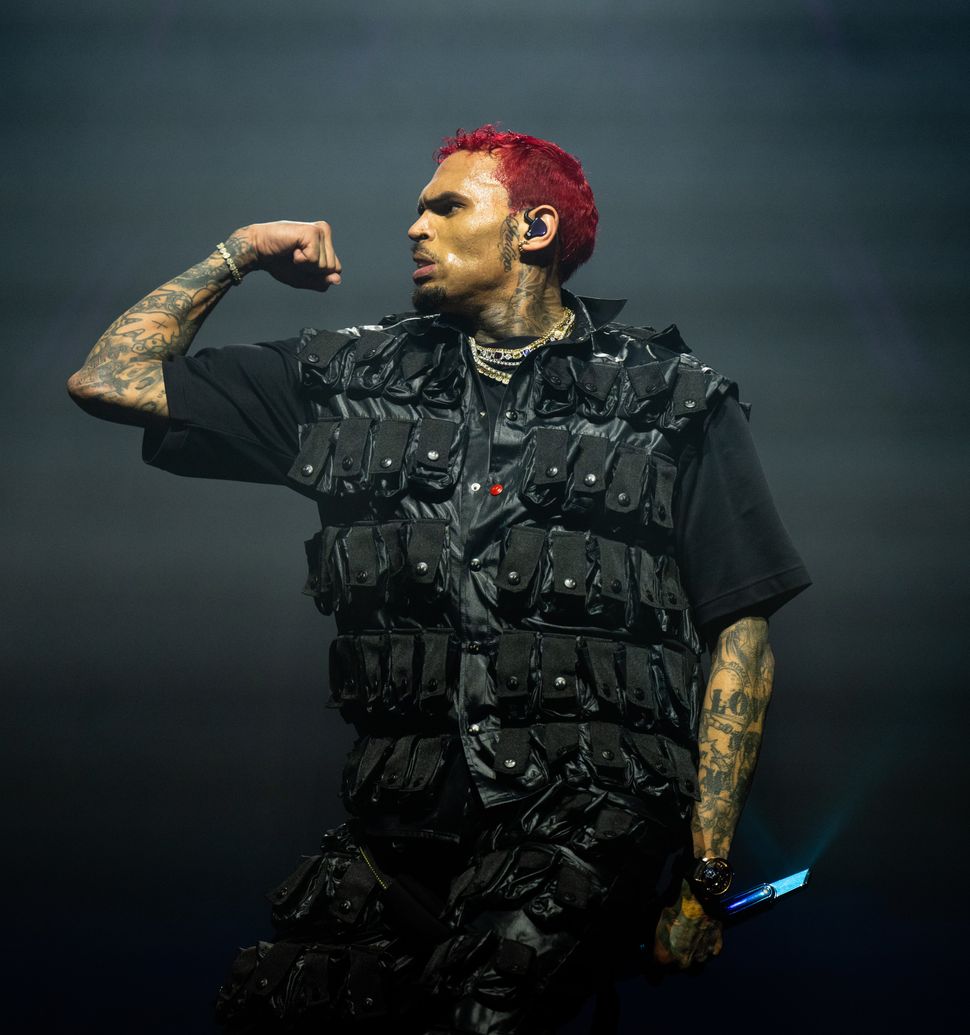

There is a wide spectrum of grievances that some people are willing to ignore to enjoy their favorite art or artist — whether it’s Black women supporting Chris Brown, who has been accused of assaulting multiple Black female celebrities, or the “nightmare” that was “America’s Next Top Model,” which is full of racist, fatphobic and misogynistic moments.

According to Elizabeth Nordenholt, co-creator of the now-defunct “Your Fave Is Problematic” podcast, that defense can often be chalked up to one’s emotional connection to entertainment. (The podcast is not connected to the Tumblr blog of the same name.)

“We all connect with media because it evokes something in us, right? And there’s, eventually, a cost analysis that you make with a problematic fave,” Nordenholt said. “Are the things it’s evoking in me important enough that I can look past the issues? What am I getting, and what am I losing for this? And I think people are gonna have different lines.”

She continued, “I think about the things where there’s still something in the story, in the music or whatever that matters. I think it speaks to a really important reflection of the human condition.”

“Your Fave Is Problematic” was created by former roommates Nordenholt, 34, and Kristen Bennett, 40, in 2016. “She was like, ‘I just kind of want to have a podcast that’s like the conversations that we have around the kitchen table,’” said Bennett, recalling Nordenholt’s initial pitch to her for the podcast.

When did the media we consume become emblematic of who we are, or has it always been? Is it reasonable to tether your own morality to entertainment, and what does it suggest about your values? How does having a problematic fave complicate the concept of cancel culture?

YFIP’s tagline became “a podcast where we take your favorite thing and ruin it.” In reality, it’s two friends trying to walk the tightrope of engaging in fandom while being socially conscious consumers. The duo’s first episode was released in July 2017; it analyzed depictions of sexual assault on screen, female archetypes and white saviorism on America’s favorite show at the time: “Game of Thrones.” The podcast, and its corresponding Facebook community, served as a medium for Nordenholt and Bennett to facilitate nuanced and thoughtful conversations that other online spaces didn’t leave room for.

The podcast’s launch coincided with the throes of Trumpism and the impact of the #MeToo movement; the final episode aired January 2021. In that time, there was a groundswell of frustration that changed the way we engage with men in power but also celebrity culture at large. People felt empowered to call out, identify and name the abuse they endured at the hands of powerful figures. Their list of subjects to address became lengthier and lengthier.

Bennett, who lived in Los Angeles at the time, denoted a landmark shift in the concept of a problematic fave since they launched their podcast.

Today, you can be regarded as a Bad Person™ for continuing to engage with a problematic celebrity’s music, films, etc. It is a dynamic that often plays out online and IRL. Bennett says it’s a reflection of how the definition of “cancellation” has been co-opted and divorced from its original context. In the last several years, to “cancel” someone has meant a range of things: a personal reckoning, or public displays of self-righteousness or even, a rubric for judging the values of people around you.

Today, you can be regarded as a Bad Person™ for continuing to engage with a problematic celebrity’s music, films, etc. It is a dynamic that often plays out online and IRL.

“I grew up in a time where someone saying, ‘That’s canceled,’ was a Black thing, and it wasn’t ending somebody’s life. They were just like, ‘Girl that’s over. No one’s interested in that. Whatever,’” Bennett said. “If you used to go to a restaurant for brunch and they stopped serving your favorite meal, you’d be like, ‘Oh, we can’t go there. That’s canceled.’ It could range from something as innocuous as that to having a homegirl who was lying about you. Like, ‘She’s canceled. We don’t even fuck with her anymore.’”

Notably, Wesley Snipes’ character, Nino Brown, used the phrase, “Cancel that bitch” in reference to dismissing his girlfriend Selina (Michael Michele) in the 1991 film “New Jack City.”

Bennett’s theory behind the evolution of the word is that “primarily conservative white people who don’t know any people of color” have turned expressions such as “woke” and “canceled” into a looming, proverbial Boogeyman.

Nordenholt echoed her sentiments and expressed that cancellation has become a badge of honor for America’s conservative activists — and yet another means for white people, often wealthy, visible and powerful white people, to grasp for faux-marginalization and oppression. And of course, there are the Black male celebrities who also feed into this, notably Kanye West and comedian Dave Chappelle.

After being called out for transphobic jokes, Chappelle said, “If this is what being canceled is like, I love it,” amid a standing ovation. After Balenciaga ended their relationship with Ye over his antisemitic comments, he boasted, “I ain’t losing no money.” When a member of the paparazzi asked West, “What have you got to say to people who are trying to cancel you?” surrounding fans interjected: “You can’t cancel him, man!” West retorted. “I’m here! What we talkin’ about? We ain’t goin’ nowhere…If I ever went anywhere, we know why.”

“The right has this really strange and fascinating power to co-opt language and mold it to themselves. They’re like, ‘Oh, the left woke mob is trying to cancel me.’ And that’s clout for them,” Nordenholt said. “It’s not even about what it meant, even when we were talking about it five years ago. Louis C.K. didn’t work for a year after all that shit came out about him. Does that make him ‘canceled’? Well, he’s still working, so I don’t think so.” (Louis C.K. even admitted that the allegations of sexual misconduct, which included him masturbating in front of women, were true.)

Nonetheless, the #MeToo era ushered in a culture of accountability that was previously absent. That accountability began to trickle down to fans, too, and audiences began to evaluate their own relationships with artists and their art. The idea of a “problematic fave” served as a way to keep that emotional connection to that work or its creator, even if a fan didn’t have the language to articulate it.

“A lot of times what has happened is it becomes this projection that we do. ‘I love this thing and it’s so bad, I must be bad too.’ That kind of gives you two options when you’re thinking of it in that frame,” Nordenholt said. “I can either disavow that thing, or I have to defend it because by proxy I am defending myself.”

Navigating this cognitive dissonance, the incongruence of action and beliefs is a big part of understanding how parasocial relationships play out.

Defining the relationship IRL

Parasocial relationships refer to the media users’ imaginary relationships with media figures or media characters, said Dr. Mu Hu, an associate professor in the College of Arts and Sciences at Texas A&M University-San Antonio. Hu has spent over a decade conducting research on parasocial interaction and relationships, namely their deterioration and dissolution.

The concept of parasocial relationships is not new — the term was coined in 1956 by Donald Horton and R. Richard Wohl, but Hu noted that because media shifts over time, so do parasocial relationships. When broadcast TV was considered “new media” in the ’50s and ’60s, media users were referred to as audiences and viewers. With the proliferation of new social media — and a wider definition of “media figure” (e.g., influencers) — parasocial relationships have transformed.

Doja Cat referenced parasocial relationships as the reason why fans are overfamiliar with her online. (While that may be true, she’s also using that as license to evade criticism for dating a man who has been accused of emotional abuse, grooming and sexual misconduct.) Your imaginary relationship with your “problematic fave” is always there for you. One of the biggest accelerants of parasocial relationships is the frequent accessibility and 24/7 availability they provide.

“Harry Potter would never reject you. Harry Potter will never judge you,” Hu said. “Parasocial relationships with a celebrity or with a media figure have no such problem. Let’s say, at 3 a.m., you cannot go to sleep. You open your computer, and they’re there. They’re always available.”

When that piece of media or individual offers something for your spirit, you place significance on it. In the case of Harry Potter, audiences saw themselves in Harry and sought reprieve in the global Pottermore community, all of which were conceived by J.K. Rowling in 1997. Yet Rowling has managed to tarnish her legacy, and arguably, that of the series, by doubling down on her transphobic comments. Now, dejected and disappointed fans are left wondering if they should even watch the forthcoming “Harry Potter” TV series on Max, as profits would line Rowling’s pockets.

Most recently, Lizzo was accused by three former backup dancers of physically threatening, weight-shaming and sexually harassing them. Lizzo has denied the allegations.

The “Juice” singer, who preaches radical self-love, has been lauded as a bastion of body positivity, and been the target of loaded fatphobic misogynoir, has allegedly lived long enough to see herself become a villain. The sheer disappointment that such claims could be brought against someone who sought to be a role model for young girls still stings for so many fans.

In Hu’s research, he found that the stronger the parasocial relationship that people had with a celebrity or a media figure, the more intense or impacted they felt by the erosion of that relationship when a scandal came about.

“A parasocial breakup refers basically to the termination of a relationship due to some incidents, for instance, the death of a figure like Kobe Bryant, Robin Williams, or the finale of ‘Friends,’” Hu said. “There’s some turbulence, or an incident happens which may potentially pose some threat to the parasocial relationship. The intensity or the intimacy of a parasocial relationship may decline, so I call that parasocial deterioration.”

Hu found that the more a person liked a celebrity, the more impacted they were by their behavior, but also, they were also more willing to forgive than the average media user.

“When people really like a certain celebrity and when something like that happens, people who love them more tend to attribute the cause of the scandal to external factors,” said Hu. “‘He was drunk. He was under a certain influence. He was in a bad mood. He isn’t that kind of person.’ But when it comes to someone that they don’t like that much, they tend to attribute the factor or the cause to internal factors. Like, ‘Oh, I knew it all along. He’s always been that kind of person. I knew it.’”

Parasocial relationships gone wrong

While these relationships are entirely imaginary, they have tangible, social consequences, dictating your ability to form a community. Fandoms can be a beautiful place, but there is a dark, eerie side. Crazed “stans” who resort to doxxing, dogpiling, and unleashing death threats on anyone who criticizes their “problematic fave” are a part of that world.

In September 2022, YouTuber Kimberly Nicole Foster took legal action against Nicki Minaj stans, referred to as “Barbz,” after they posted her personal information online. Writer Wanna Thompson also spoke out about violent messages she received from some Barbz in 2018.

“The negative incidents you just mentioned,” said Hu, “it’s nothing different from a riot in the street, isn’t it? Riots usually take the form of a group. That individual is in company with hundreds or even thousands of other people, and all of a sudden, he or she feels empowered as a group and feels an urge to join. Of course, there will be some erratic, irrational behavior.”

Now, not every person who considers themselves a “stan” of a particular artist exhibits violent behavior. “Stan” is often attributed to rapper Eminem and his song from the 2000s called “Stan.” (The music video depicts an Eminem-obsessed fan named “Stan,” who eventually transforms into a bleach blonde Slim Shady and drives himself off of a cliff.)

Most people who consider themselves “stans” have a very different, more normal approach to engaging with celebrity culture, according to media scholar Stitch.

“Stanning is not seen as a negative by stans,” Stitch said. “But not in the same way that Stan in the song didn’t see that as a negative. His parasocial attachment to Eminem is different. I feel like most fans who identify themselves as stans aren’t going to behave that extreme.”

Stitch, who identifies as a nonbinary Black femme, is a millennial freelance journalist and pop culture scholar with bylines in Teen Vogue, i-D, The Verge, Polygon and other publications. As founder of the website, “Stitch’s Media Mix,” they have been studying fan behaviors and Black women in fandom for almost a decade. With degrees in history and English, they first utilized their education to analyze fandom when racist criticism arose in 2016 following news that Zendaya would be playing Mary Jane in “Spider-Man.’

In Stitch’s words, “fandom” has always been a community of fans, but it’s more than someone merely liking something. It implies a deeper level of devotion and more active, constant engagement with the subject, as well as other people who may admire — or even share “an antagonistic dislike” for — said media figure, celebrity, video game, etc.

But there is an “extreme 10% of fandom,” Stitch said.

“The average Yuzuru Hanyu fan is like, ‘He got married? Oh, that’s great for him,’” Stitch said, referring to the Olympic champion figure skater. “Then a stan is like, ‘He’s secretly gay. He has a beard. I’m gonna pretend this doesn’t exist. I wish this was me. I thought this could be me.’”

Stitch continued, “Have you ever seen the iceberg meme where it has layers? And underneath, usually, the darker the water, the more messed up the thing is? For stans, the iceberg is fandom. The farther down you go, the more extreme the behavior is, and the more obvious it is ‘stanning.’”

In 2016, Stitch noticed a shift in how literary fandoms would weaponize “cancel culture” to make judgments about other online users. If a reader “shipped” two characters, meaning they wanted two characters to enter a romantic or sexual relationship, and someone disagreed? All hell would break loose.

“If other people decided that pairing was a negative thing, you were held accountable for it,” they said. “People would make blogs dedicated to calling out people who have the ‘wrong’ preferred pairing.”

They continued, “Even though that started with non-celebrity fandoms, it seems to bleed into how stans talk about their object of affection. I love BTS. I adore BTS. But one of the things I found really frustrating about the fans a couple of years ago, is that if you ever said anything critical — if you talked about J-Hope’s hair or pointed out an issue of anti-Blackness — it was framed as racist against these Korean idols. That’s not what that is. That is a new fan finding out that their new fave is problematic.”

Stitch has had direct experience with how violent fandoms can be; they have been the target of online and offline threats as a result of criticizing and analyzing particularly volatile fandoms, they said. During the “racial reckoning” in the summer of 2020, they wrote about how activism from K-pop idols made headlines, but Black fans still have to wade through racism within the community — be it when a member of Enhyphen said the n-word or the fact that K-pop extrapolates heavily from Blackness. Moreover, they’ve been cited in reported pieces urging for the necessity of Black safe spaces in K-pop fandom.

Stitch’s nieces played them a full video compilation of problematic things BTS has been accused of, in an attempt to open their eyes and prove they shouldn’t be a fan. Despite everything, Stitch is still a self-proclaimed K-pop and BTS fan, with a photo wall of lead singer Kim Namjoon in their room. Deciding who gets to set the barometer for what behavior is too problematic — especially when they’re not a part of the community that has been transgressed — is increasingly difficult.

“Even if we are in the community, it’s so gross as a Black person to see another Black person react to a celebrity’s anti-Blackness with, ‘Well, I’m Black and I’m not offended,’ or, ‘Well, I’m Black and I forgive them,’” Stitch said. “You don’t speak for all of us. That is your forgiveness and you’re welcome to dole it out, but you don’t get to decide that anybody else has to like that celebrity or has to be nice to that celebrity afterwards.”

Stitch argues that it isn’t the art itself that is problematic, but rather, how we as audiences, viewers and consumers engage with and talk about said art. What makes stans bad, said Stitch, is not their affinity for something. It’s the doxxing, the death threats, and violent harassment that they sometimes participate in to protect the art or the artist.

“Liking a problematic piece of media or celebrity in and of itself isn’t a bad thing, right? A lot of people think that consumption alone is the problem, which is kind of not true. What you like isn’t the problem, how you like it is,” Stitch said.

In a New York Times op-ed published February 2021, Liat Kaplan claimed credit for the “Problematic” Tumblr blog in 2013, and unveiled the scrutiny they endured while running the account and shared regrets they have as the creator.

“Who was I to lump together known misogynists with people who got tattoos in languages they didn’t speak? I just wanted to see someone face consequences…Looking back, I was more of a cop than a social justice warrior, as people on Tumblr had come to think of me,” Kaplan wrote. “For years, I’ve regretted the spotlight I put on other people’s mistakes, as if one day I wouldn’t make plenty of my own. My brain wasn’t ready for nuance.”

Upon reflection about previously aired episodes of “Your Fave Is Problematic,” Nordenholt and Bennett agree that if they listened today, their opinions and takes on various topics may, in fact, have changed.

“And it’s either because more stuff has since come to light or just because I’ve done my own growth,” Nordenholt said. “A lot of times, it’s probably both.”

But we cannot predict when our fave will inevitably mess up, nor can we be the arbiters of forgiveness when it is not our trust that has been violated. However, what audiences can do is be more honest. Whether the concept of a “problematic fave” is reflective of our moral shortcomings may actually be secondary to simply understanding that we should acknowledge a celebrity’s said problematic behavior, instead of giving them a special designation to assuage our conscience.

“Your Fave Is Problematic” blog creator Kaplan wrote in The New York Times that they thought about deleting their blog, but they ultimately won’t — because that would “erase the errors” of their judgment and someone would later retrieve it anyway.

“I’m not saying that I should be canceled for my teenage blog. (Please don’t!),” Kaplan wrote. “I just know what we all should know by now: that no one who has lived publicly, online or off, has a spotless record. The internet, after all, never forgets.”