JACKSON, Miss.—The first thing you see when starting a tour of the historic and regal Mississippi Governor’s Mansion is a lot of pink. Pink walls, rugs infused with salmon splashes, and antique magenta and gold chairs. A delicate pink chandelier glows overhead in the formal Front Rose Parlor in the oldest part of the mansion in downtown Jackson. Each room’s nickname in the older part of the mansion is its color. There’s also the yellow room, gold room and so on.

It was a family affair on Sept. 20, 2023, when Gov. Tate Reeves, his wife Elee Reeves and youngest daughter Maddie greeted a Mississippi Free Press team, including Editor Donna Ladd and photojournalist Imani Khayyam at the public entrance to the 181-year-old mansion. The Mississippi Free Press had reached out to his office to fact check claims made by a national publication about expenditures spent on renovating the Governor’s Mansion.

In response, the governor insisted on providing a personal tour himself. His wife and first lady Elee Reeves, dressed in pink, oversaw the renovation and led much of the tour with her daughter, who would reveal that her personal motive was really to show off her handiwork in cleaning up her own room to get ready for the uncommon media tour.

The Daily Beast reported on Sept. 13, 2023, that Reeves had spent millions in taxpayer dollars renovating the Governor’s Mansion. Senior Political Reporter Roger Sollenberger cited documents he obtained through a public-records request.

The article says Reeves sold his personal home in Flowood, in Rankin County just east of Jackson, and moved his family into the mansion and immediately began spending $3.3 million on renovations to fit the Reeves family’s taste, with $900,000 of that coming from private funding.

The most expensive part of the renovations went toward safety improvements, with $600,000 spent on asbestos abatement and $525,000 on security. Some funds went to repair items in the oldest and most historic part of the building with oversight of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, which maintains an office in the basement.

The Daily Beast article also noted that taxpayers “footed the bill for more than $100,000 in family living space renovations” and $20,000 on garden work. The report attracted significant attention, especially from political opponents.

The outdoor upgrades included the planting of a much-criticized “meditation garden,” a small limonaia (an architectural structure used for lemon trees) and several irrigation system upgrades. The article goes on to list various other renovations to staff areas, hazardous areas and a renovation to allow accommodations for Reeves’ family, including his three children.

A Crumbling Landmark

With each room of the oldest part of the mansion having its own theme, color scheme and decorated with time-period specific furniture, those spaces are beautifully designed and pay tribute to the building’s historical roots.

Architect William Nicholas designed the Mississippi Governor’s Mansion and saw it to completion in 1842 for $50,000, or about $1.8 million in today’s dollars. The mansion’s brochure notes that it is the second-oldest continually occupied governor’s residence in the U.S.

The mansion survived the Civil War, but Union leaders used it for at least one gathering during the Union occupation of the capital city. Today, a portrait of Mississippi Gov. John A. Quitman during battle hangs in the mansion with a switch to light it up. Quitman served as acting governor from 1835 to 1836 as a Whig and then was elected to service from 1850 to 1851 as a Democrat and lived in the mansion.

Quitman was a wealthy slaveholder who owned four plantations: Belen in Holmes County; Springfield near Natchez; Palmyra in Warren County; and Live Oaks in Terrebonne Parish in Louisiana.

He was also a leading “Fire-Eater”: a group of Southern Democrats who were avidly pro-slavery and helped push the South into seceding and then starting the Civil War over the right to maintain slavery and force it on new U.S. states. Quitman County and the City of Quitman, Miss., in Clarke County are both named for him.

Like his predecessor governors since Kirk Fordice, Gov. Reeves has long honored the Confederacy, every April declaring Confederate Heritage Month in Mississippi.

By the late 19th century the mansion fell into disrepair, and many locals called for it to be demolished. But the Legislature approved $30,000 for renovation in the early 20th century, about a million dollars today.

Reeves’ mansion renovation included the construction of a two-story family quarter. For decades, the mansion had received appropriations to repair and furnish the mansion, but those did not stop it from falling into a state of disarray. The brochure went on to explain that by 1971, only a major renovation project could repair the damages.

Soon after Democratic Gov. William Waller’s 1972 inauguration, the Legislature allocated funds for a $2.7-million renovation and restoration. On June 8, 1975, officials opened the newly restored governor’s mansion to the public and, within the following year, the U.S. Department of the Interior designated the mansion a National Historic Landmark for its architectural and historical significance.

The two-story mansion is split into two sections; one is the historic space, and the other is the family living quarters.

The historic part of the mansion was largely renovated in the late 19th and early 20th century and remains accurate to the time in which it was built. The public can tour the historic part of the Mansion for free with an on-site Department of Archives and History employee.

When the Reeves family moved in, the roof was leaking and causing significant damage to the historical part of the mansion, the governor said, adding that leaks were just the beginning of the dangers inside the building.

‘Friends of the Mansion’

On the tour, Gov. Reeves was relaxed as he explained that the Mississippi Department of Archives and History controls all the funding and renovations done in the mansion.

That means, he added, that neither he nor the first lady can make any aesthetic changes to the historic part of the building and must use period-specific fabrics and furniture when replacing worn parts and materials in the mansion.

For rooms like the Front Rose Parlor and Gold Parlor, the nonprofit Governor’s Mansion Foundation Inc., raised private funds to reupholster furniture pieces and replace other ones, and regild items such as mirrors and accessories with Mississippi Department of History and Archives approval.

“Any project that is done on this one-square block has to be approved by the Board of Archives and History,” Reeves told the Mississippi Free Press. “All of the furniture is historic in that it is from that particular time period, in the 1830s.”

Former Democratic Gov. William Winter and his wife Elise Varner Winter started the Friends of the Mansion committee to work on and raise funds for the historic parts of the mansion, Elee Reeves said. But her husband added that the mansion remained largely untouched for several years until his wife spoke to Mississippi Department of Archives and History Director Katie Blount.

“Elee had gone to Katie Blount and said we’d like to raise some private money to refurbish some of these historic pieces, and she said there is already a c3 set up to do that, but it is under the control and auspices of Archives and History,” the governor explained.

The Friends of the Mansion Committee, spearheaded by the first lady, is largely open to any community members and allocates private funding through various events that take place on the mansion’s grounds.

“We have a Friends of the Mansion Committee we’ve started; it is $50 to join, y’all are welcome to join,” First Lady Reeves told the Mississippi Free Press team. “We have a garden party and a Christmas party each year.” Mississippi Christian Living previously reported in 2021 that Elee Reeves had resurrected the committee.

But the nonprofit 501(c)(3) the governor referred to is the Governor’s Mansion Foundation. Its board includes Reeves’ campaign treasurer Kristin McDevitt; First Tower Loan CEO Franc Lee of Flowood who has donated tens of thousands of dollars to the governor’s campaigns; longtime friend and Mississippi State political science professor Whit Waide; Hederman Group consultant Melissa Hederman who previously served as the chief development officer for Mississippi Today; and Cora Gee, who has worked with both Democratic and Republican administrations in the state.

The Daily Beast reported federal tax records showing that anonymous donors contributed $900,000 toward the mansion’s renovations and restoration.

Scary Leg of the Tour

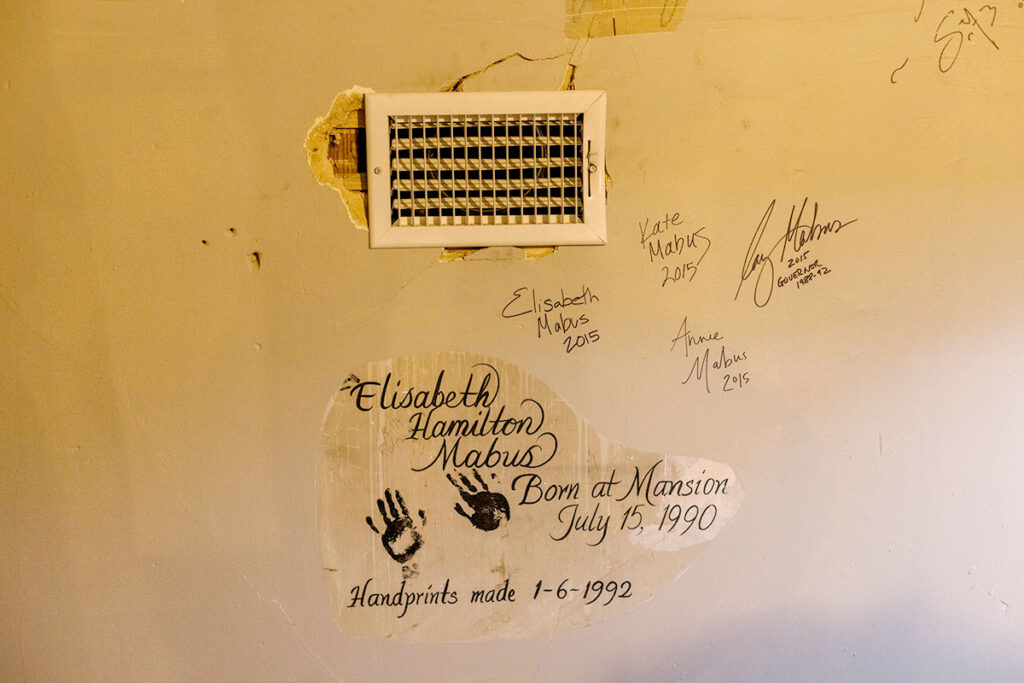

After the Mississippi Free Press tour moved from the ornate historic areas, the family said to “be careful” as they led the team up a rickety set of wooden stairs. This leg of the tour went past occupants’ handwritten signatures in an unused and dimly lit attic room containing walls signed by previous family members who visited in 2015—including Democratic Gov. Ray Mabus’ family Elisabeth, Kate, Anne and Ray, as well as child hand prints of Elisabeth who was “Born at Mansion July 15, 1990.

Winnie, Carlene and Claudia Brewer also signed the wall in July 1906, along with various other visitors and occupants over the decades.

The reporting team emerged onto the mansion’s roof through a short exit door, maybe 4 feet high, that looks more like a protruding doghouse from the top of the building with marvelous views of Jackson all around.

Aside from the historical renovations, the Reeves family used taxpayer funds in the historic and private quarters of the mansion. Some of these renovations included replacing rotting wood on the roof’s balustrades.

“Of the projects that were criticized recently, approximately $273,000 of that was used for roof balustrade repair and approximately $499,000 is kitchen and laundry rehabilitation,” Reeves said on the roof. “That’s about $800,000 of total expenditures that have been made by the taxpayers.”

The Daily Beast reported that Reeves “has over the years received $11,750 (in campaign donations) from entities who scored mansion contracts, most of which came from Wier Boerner Allin Architecture PLLC.” State law does not forbid such contracts, however.

‘Readiness’ For Three Daughters

Gov. Reeves said while standing on the mansion’s roof next to his wife that he and his family decided to sell their Flowood home and fully move into the Governor’s Mansion in 2020 during the height of the pandemic. Due to his workload at the time, fully moving into the mansion, which not all previous governors and families have done, made it more convenient and his family could all be in the mansion as many sheltered at home during the pandemic.

It was the first time young children had lived in the mansion in decades, and some changes were necessary to accommodate his three daughters, the

governor and his wife said.

This move, however, was not pleasing to all his daughters, two of whom were teenagers by then, and that helped motivate many of the renovations in the private quarters, which are small for a family that size. Reeves said he promised to compromise with his daughters on the move by making renovations, such as allowing his older daughters to have their own rooms in the basement of the mansion, all of which the family showed to the team along with their main family quarters upstairs, while not allowing photos of private spaces.

Renovating the basement space for the two Reeves teenagers turned up asbestos in the mansion’s basement. Officials also found asbestos in areas of the mansion where staff work daily. Asbestos can cause diseases like pleural disease, mesothelioma, lung cancer, and asbestosis, a chronic lung condition solely caused by high exposure to asbestos fibers in the air.

“When asbestos is found, you have to tear out the entire floor and go into the original,” Reeves said as he walked the reporting team through the basement. “This floor is all new and was put in once we moved in.”

Before the Reeves family moved into the mansion, there were multiple layers of asbestos in the flooring. Elee Reeves explained that the flooring was consistently replaced because multiple layers of flooring can be put on top of asbestos to alleviate the issue; however, after a while the floor will collapse. She said that the floor began to collapse once the family moved in.

The governor said the taxpayer-funded renovations in the living quarters, including the basement, totaled about $129,000 for “family readiness.”

Cleaning Up Asbestos

The Daily Beast also criticized kitchen and laundry repairs in the staff areas. The governor showed the reporting team where asbestos had existed in areas where both the governor’s and the first lady’s staff of state employees work, as well as the security team (called the “Executive Protection Division”) in the mansion. They thus had to put new flooring in the offices of both the mansion’s chef and in the Mississippi Department of Archives and History office—where renovations were overseen and approved—as well as in the security lounge areas and staff bathrooms.

Significant security upgrades included switching from old analog security cameras, many of which didn’t work, to new digital cameras. “I would argue if (I was) living here by myself there would probably be less of a need for security, but since I’m traveling a lot and my wife and three daughters are here, it’s a really important piece to me. I’m making no apologies for ensuring their safety and security while I’m here,” Reeves said in the basement.

Taxpayers also paid $500,000 toward a vent-hood project to repair parts of the vent and to get the commercial kitchen up to code.

“So of the 2.3 to 2.4 million that has been spent in total since I’ve been here in public money, $800,000 are for those two projects,” Reeves said, referring to the updated commercial stove vent system and the asbestos cleanup and new flooring.

Reeves also pushed back on mentions in the Daily Beast article, written by out-of-state reporters who did not visit the mansion, of a wet bar installed by Gov. Haley Barbour and a new ice machine installed on his watch.

Reeves criticized the Daily Beast’s article, arguing that it muddled the difference between publicly funded and privately funded renovations at the governor’s mansion.

“One of the unfortunate things is the lack of differentiation between what private money paid for and what public money paid for,” he said. “The focus on the meditation garden, for instance—(it) was fully paid for by private money.”

Enter the Meditation Garden and Limonaia

You might not know it from the Daily Beast article, but there was nothing extraordinary about the oft-criticized Meditation Garden, other than the small Limonaia structure. The garden is beautiful and well-maintained and filled with plants native to Mississippi including Rose of Sharon/Lenten Rose, Climbing Hydrangea, Boxwoods and lemon trees. However, the addition is far from an actual meditation garden, which is more of a stone walkway through a narrow strip of plants and flowers with one small stone bench that might hold two small people sitting close.

First Lady Reeves said that they had never called it a “meditation garden” to begin with; in fact, she said, it was a colleague who called it that during the garden upgrade’s planning stage. It is called a “Meditation Garden” on the back of a colorful card Elee Reeves provided to the Mississippi Free Press team.

The recent additions to the gardens join a wide variety of plants provided and funded by garden clubs and various fundraisers over the decades. In 1975, the Garden Clubs of Mississippi Inc. funded a stone fountain and garden benches, and the Mississippi Federated Women’s Club paid to build the East Gazebo. Mississippi schoolchildren helped with a “Dimes for the Mansion” fundraiser to pay for the West Gazebo. The Garden Club of Jackson maintains the Cutting Garden.

The governor said the garden space was under-used when the family moved into the mansion, and his wife had a strong interest in making it a source of pride on the grounds—much as U.S. First Lady Michelle Obama had done with garden upgrades and additions at the White House. The Department of Archives and History approved the building of the Limonaia using donations. He noted that former Democratic Gov. Ray Mabus had planted a tree in 1990 after his daughter Elisabeth was born there and pointed it out to the team.

Reeves said private funds paid for 100% of the cost of the garden, which his wife helped raise. He said taxpayer money is used for regular building upkeep and upgrades, such as the replacement of the roof, the replacement of the Vena hood for the kitchen, asbestos abatement and the irrigation system.

“The standard I use is that if it is something that will be here forever, then I would argue it is a legitimate expense of the Department of the Finance and Administration to upkeep it,” he said. “If it is something being put in at the request of the first lady or the request of the governor, then it’s incumbent upon the first lady and the governor to raise private funds to do it.”

Reeves believes that the Daily Beast article insinuated that he was trying to hide the cost of the expenditures used toward the mansion, whereas he says all that information is public due to him regularly hosting press conferences in the mansion and regular tours of a historic building that are open to the public.

“It is used by the public. We’re proud of it, and I’m proud of the work Elee has done to make this place a little bit better than we found it. We’re hopeful more people will be able to enjoy it,” Reeves said.

Donna Ladd contributed to this report.