The economy is churning out mixed signals these days, with a flurry of separate reports suggesting America is experiencing high growth and job creation — and rising poverty.

But Carolyn Solar, who leads an Inland Empire food bank, isn’t confused.

“For us, the numbers sort of speak for themselves,” said Solar, chief executive of Feeding America’s operations in Riverside and San Bernardino counties.

Specifically, Solar was referring to the number of people served by her agency’s Senior Mobile Pantry program, which takes free food directly to people ages 60 and older. In January, the Mobile Pantry client list was 1,600; by September it was up to 2,300.

“It’s pretty clear,” Solar said. “Need is going up around here.”

In California, need is going up everywhere.

A report issued recently from the Public Policy Institute of California concluded that from late 2021 through the first quarter of 2023 the state poverty rate, including people of all ages and demographic profiles, jumped from 11.7% to 13.2%.

That defies a trend in which poverty rates, in California and nationally, fell during the pandemic. Economic forces throughout 2020 and much of 2021 played out in ways that weren’t expected, initially because of the layoffs and rehiring sprees that happened during lockdowns and high case counts, and later as federal and state relief efforts helped some lower-wage workers and others stave off homelessness.

Though California’s new poverty rate is well below the pre-pandemic rate (16.4% in 2019) economists and others suggested the swift upturn found in the PPIC report is troubling.

“What we’re seeing now is people who are working but still struggling. It’s a combination of people having better jobs, sure, but it’s also the expiration or reduction of a lot of the safety-net policies we had during the pandemic,” said Caroline Danielsen, a senior fellow at the PPIC and co-author of the report “Who’s in Poverty in California,” which was issued earlier this month.

“The (safety net) programs we created during the pandemic, like the child tax credit and expansion of food assistance, really did more to support families than anything we’ve seen in recent times,” she added.

Danielsen was commenting on Thursday, Oct. 26, the same day the Commerce Department issued a report saying the U.S. economy grew at a rate of 4.9% during the third quarter, one of the more robust non-pandemic quarters in at least a decade. Other reports – about job creation and declining (though stubborn) inflation – suggest those forces in the economy also are strong.

Danielsen acknowledged that such factors can stave off poverty, but said simply that the economic issues nudging people into poverty – fuel costs, painfully high rents, less food assistance – are even stronger.

The PPIC report, conducted with researchers from Stanford, uses a formula that measures income in a specific area against the costs of necessities, including housing and food, in that same area. Based on that, the report noted that Latino and Black residents, and recent immigrants, are more likely than Asian and White residents to earn an income that qualifies as “poor.”

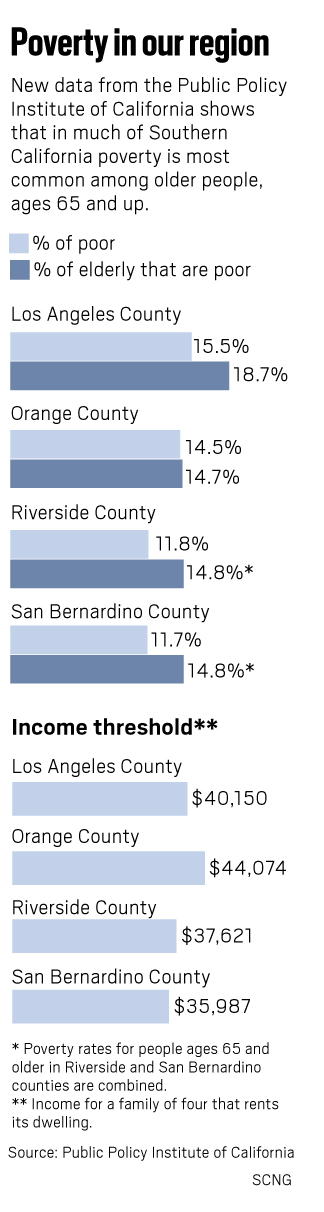

But the report also broke down poverty rates based on age and even geography. Within that framework, in the region that includes Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties, poverty is highest in two groups – older people, age 65 and up, and children, age 17 and younger – who live in otherwise high-income communities.

“We do help a lot of older people,” said Solar, who helps feed people in the Inland Empire. “But it feels like we’re seeing everybody right now; everyday people, educated people, people with jobs. Everybody.”

The PPIC report offered some findings that defy long-held perceptions about where poor people and wealthy people live, including:

• Los Angeles County, a place with Malibu and $44 salads and one of the nation’s biggest skid row districts, has the highest poverty rate (15.5%) of any county in Southern California and is third in the state after Yolo (19.5%) and Santa Barbara (16.9%) counties.

• The poverty rate in Orange County, with well-coiffed beach towns and the region’s highest home prices, is 14.5%.

Meanwhile, two counties long viewed as less economically glitzy – Riverside (11.8%) and San Bernardino (11.7%) – have strikingly lower poverty rates of than their supposedly wealthier neighbors. In fact, when taking into account the comparative costs of housing and other essentials, the incomes that qualify as “poor” according to the PPIC suggest living in the Inland Empire is about 25% less expensive than in counties closer to the ocean.

Danielsen said the Southern California findings reflect national patterns, with coastal states often having higher poverty rates – when the measurement is based on local incomes and local expenses – than non-coastal states.

“Depending on which year you’re talking about, California usually is either the state with the highest poverty rate or in the top three, at least when you take into account incomes versus the state’s standard of living and the safety net ratings,” Danielsen said.

“We’re a high-wealth state, and also a high-poverty state, unfortunately.”

One finding in the PPIC poll that might push poverty rates higher in the future is the level of economic desperation among older people. People age 65 and older, statewide, are the age group most likely to be poor in California. They’re also the one age group that’s expected to grow over the next three decades.

Today, older people account for about 17% of California’s population. But with birthrates falling and people living longer, the elder share of the overall population is expected to be closer to 25% by the late 2040s.

If other economic trends hold, that surge of older people also could mean a long-term surge in poverty.

In all four local counties, the average Social Security check (about $1,830 a month, according to federal data) falls below or barely covers the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment. Though there isn’t data on how much locals rely on Social Security, national data shows Social Security checks represent more than half the monthly income of about 37% of men and 42% of women age 65 and older.

“It’s probably a bit of a harbinger,” Danielsen said, referring to PPIC’s findings related to older people living in poverty.

In some ways, older people already are struggling in Southern California, whether or not they currently qualify as “poor.”

A key reason is the high cost of keeping a roof over one’s head, particularly for renters.

A 2022 survey from the U.S. Census Bureau found that for people 65 or older who live in Los Angeles and Orange counties and have an income of $40,000, rent typically eats up 53% of their income. For people in that income range who live in Riverside and San Bernardino counties, the figure is 45%. For people with income of up to $70,000, rent eats up 35% in the Los Angeles/Orange County market and 33% in the Inland Empire.

That suggests a world of older people who are living close to a financial cliff. Already, people 50 years old and older are the fastest-growing group of those who are newly homeless in Southern California.

Danielsen said her group’s report takes into account home ownership rates and equity wealth – factors that, in theory, could push many older residents out of poverty. But even with those measured into the picture, she said older people are currently the poorest.

“This isn’t what we usually expect when looking at seniors,” she said. “But it’s what’s happening right now.”