Two and a half years into the pandemic, and it finally happened. Not COVID-19, but a COVID-related hate incident. It didn’t happen in New York, where anti-Asian hate crimes spiked by 361% last year. Nor did it happen in California, home to more than 6 million Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders, 28% of whom have witnessed or experienced a hate incident.

It happened on the grounds of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, where I am spending the academic year on sabbatical.

One quiet morning, I went out for a run. Walking ahead of me was an older, white woman. As I ran past her, she screamed, “Social distancing!” While stunned, I didn’t respond until moments later after she screamed, “F*CK YOU!” at which point I stopped, turned, looked directly at her, and calmly said, “DO NOT talk to me like that.” She proceeded to yell, “You saw me from behind! You should keep your distance! You see I’m wearing a mask!” to which I responded, “Since I’m coming from behind, how could I have seen that you’re wearing a mask?”

Without acknowledging what I said, she proceeded to scream, “You’re threatening my life by breathing hard while jogging past me! You’re F*CKING threatening my life by breathing on me!” Well over six feet away from this hysterically screaming woman, I repeated, “DO NOT talk to me like that. DO NOT curse at me.” She then turned away from me and shouted, “I’m not having this conversation!”

Believing that this was the end of the exchange, I continued running, but when she was far from me, she screamed even more loudly, “You’re F*CKING worried about a four-letter curse word when you’re threatening my life by breathing on me! I hope you get run over by a car!”

This woman never used an anti-Asian slur, so this would not be considered an anti-Asian hate incident. But I ask myself, would she have felt that a white woman jogging was threatening her life by breathing? And would she have screamed and cursed at a white woman as she did so boldly with me?

Anti-Asian violence, brutal physical assaults, and heinous murders of Asian Americans during the pandemic have captured the nation’s attention, but far more common are incidents like the one I experienced. Last year, 33% of Asian Americans have been called names or insulted, 30% have been the target of offensive physical gestures, 11% have been coughed on or spit on, and 30% have been on the receiving end of the xenophobic taunt, “Go back to your country!”

Source: Jennifer Lee and Karthick Ramakrishnan, “A Year after Atlanta,” AAPI Data, March 16, 2022. Click the image to view it full-size in a new tab.

Source: Jennifer Lee and Karthick Ramakrishnan, “A Year after Atlanta,” AAPI Data, March 16, 2022. Click the image to view it full-size in a new tab.

Asian Americans who have lived through two and a half years of exhaustion, mourning, anger, and fear, see themselves in these statistics. For many non-Asian Americans, however, they come as a surprise.

In part, the surprise stems from the absence of the fraught history of Asian Americans in narratives of America, including the collusion of science, medicine, and law in medically scapegoating Asians as vectors of incurable diseases. And in part, it is because the most popular narratives of Asian Americans tout their high level of education, median household income, and intermarriage rates. More than one-quarter of Asian Americans are interracially married, and among the U.S.-born, the share is nearly double that. Based on these indicators, some social scientists conclude that Asians are following in the footsteps of their European immigrant predecessors and are the next in line to become white.

But what happens when we shift the frame from the social scientists who study assimilation and privilege to the voices of the populations we study? A different narrative emerges.

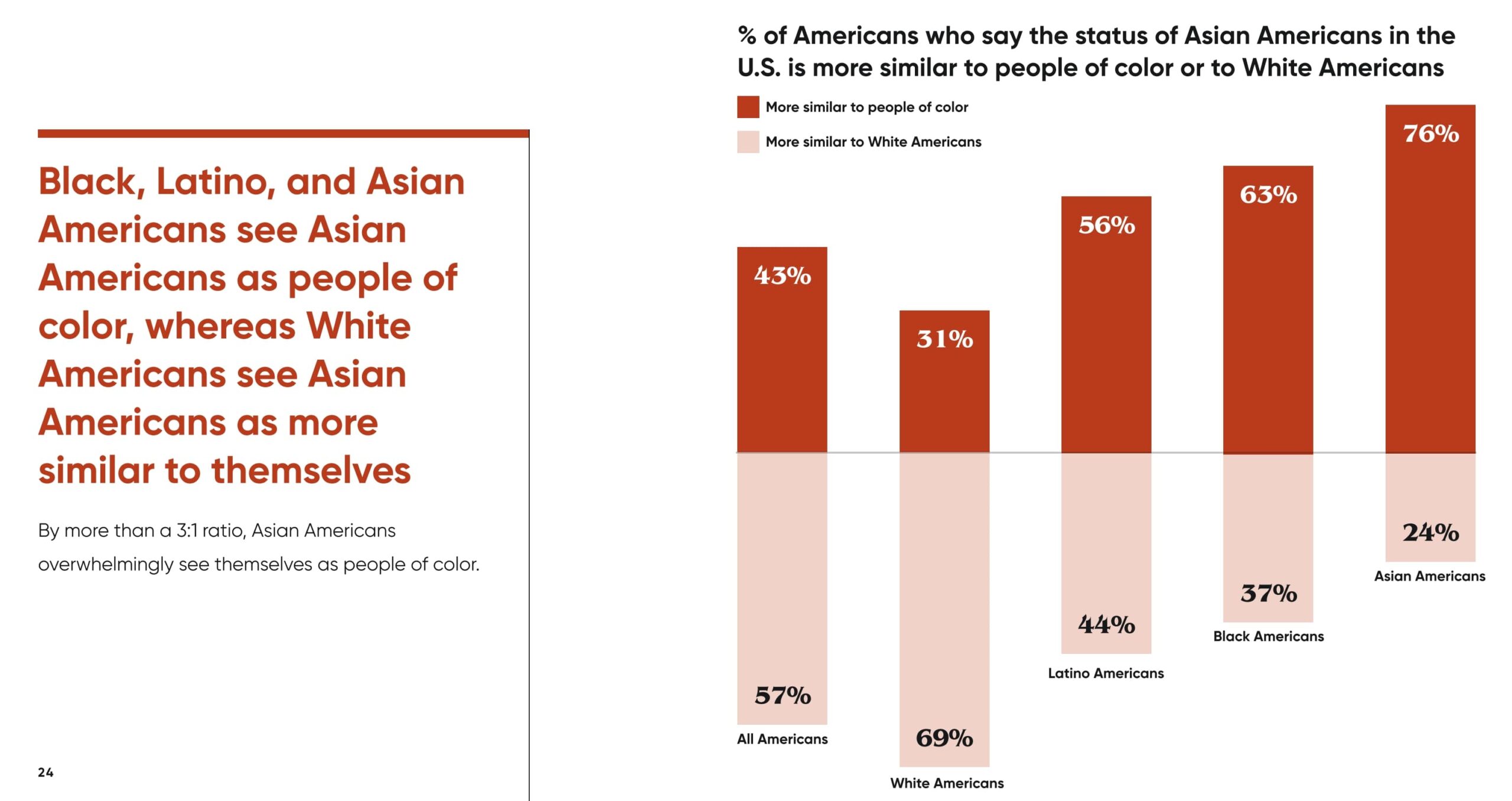

First, the majority of Asian Americans do not identify as white, nor do they perceive their status as white adjacent. Rather, 63% of Asian Americans identify as a person of color, and 76% perceive their status as closer to people of color than to whites.

Source: STATUS Index Report 2022. Click the image to view it full-size in a new tab.

In addition, the majority of Black Americans (63%) and Hispanic Americans (56%) also perceive Asian Americans as closer to people of color than to white Americans. By stark contrast, 69% of white Americans perceive the status of Asian Americans as closer to white people, pointing to a disjuncture in the way that white Americans perceive Asians compared to all other groups, including Asian Americans.

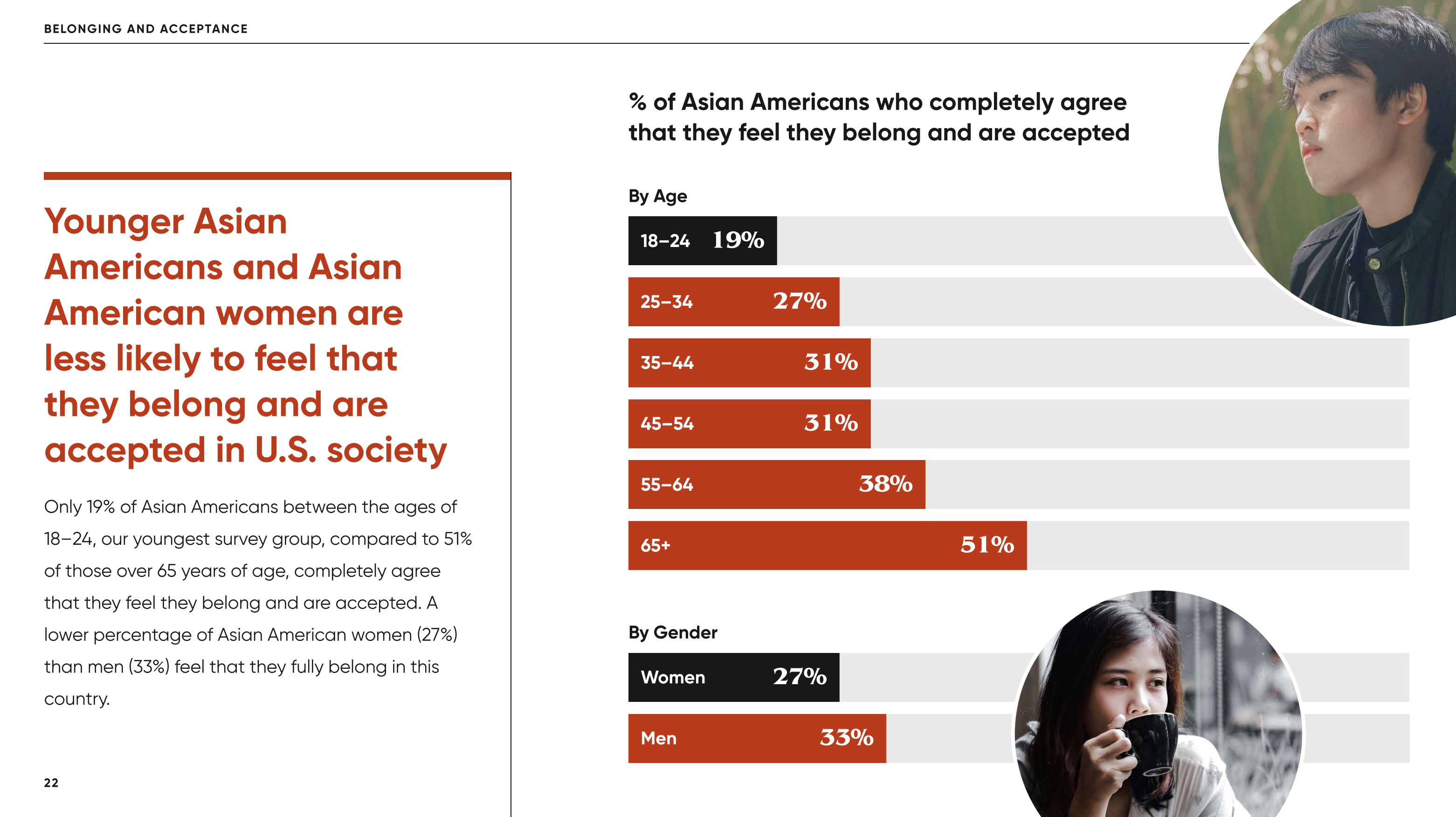

Second, when we ask Asian Americans whether they feel they completely belong and are accepted in the United States, a mere 29% of them feel this way. Indeed, Asian Americans are the least likely to feel they completely belong compared to Black Americans (33%), Latino Americans (42%), and white Americans (61%). The feeling of not belonging is especially acute among Asian American women—who are twice as likely to be interracially married than Asian American men—and young adults who are more likely to be U.S.-born.

Source: STATUS Index Report 2022. Click the image to view it full-size in a new tab.

Source: STATUS Index Report 2022. Click the image to view it full-size in a new tab.

These findings contradict presumptions that Asians are honorary white people, which also rest on the notion that the boundaries around the Asian category will be as permeable as they were for European ethnics. History has proven that this has never been the case. Moreover, Asians—including multiracial Asians—who have been in the United States for generations continue to experience insults, harassment, and xenophobia making the prospect of becoming white seem implausible. At no moment in recent history has this become more evident than during the COVID-19 pandemic when 1 in 6 Asian American adults experienced a hate incident.

Ensuring that the experiences, attitudes, and perceptions of Asian Americans are included in national data collection efforts will enable us to disrupt the narrative that Asians are becoming white, are honorary whites, or white adjacent. This also requires a commitment on the part of social scientists to take experiences, belonging, and identity as seriously as we take education, income, and intermarriage in our studies of racial progress, inequality, and assimilation.

University degrees and professional positions are no safeguards against COVID-related hate, as my experience and that of millions of other Asian Americans readily attest. That 72% of Asian Americans worry about being a victim of a hate crime, and 34% have changed their daily routines due to the worry underscores the wide gap between the way social scientists often measure assimilation and the way that Asian Americans experience it.