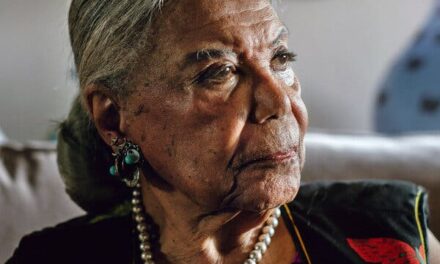

By Genoa Barrow | OBSERVER Senior Staff Writer

Former Sacramento resident Stephanie Shepard is helping lead the charge to raise awareness about disproportionate cannabis sentencing across the country. The OBSERVER spoke to Shepard, who shares her personal connection to the work. She was convicted of conspiracy to distribute marijuana in 2010. After serving nine years of federal time, she was placed on probation for an additional five years. Shepard, 54, is now a leader with the nationally prominent Last Prisoner Project.

Q. When did you leave Sacramento?

A. I grew up in Sacramento. I moved to New York in 2005 to pursue a real estate career.

Q. What circumstances led to your conviction for conspiracy to distribute marijuana?

I was charged with conspiracy to distribute 1,000-plus kilos of marijuana. It was a first-time, nonviolent charge resulting in a mandatory minimum 10-year sentence in federal prison. I was released in 2019.

Q. When you were arrested/charged, did you think you’d end up spending years in prison for weed? For your first offense?

A. Absolutely not. Cannabis may have been illegal, but I never looked at it as a punishable offense, less only something that could result in a 10-year prison sentence.

Q. We hear a lot about Black men and marijuana charges, but not necessarily Black women. Care to address that?

A. The disparities in sentencing when it comes to Black people is alarming to say the least. Black people are four to five times more likely to receive a long sentence for cannabis. As a Black woman, I felt disposable. The jury deliberated for less than an hour before taking away 10 years of my life.

Q. Can you speak on the toll that the “war on drugs” and drug policies have had on the Black community?

A. The war on drugs is riddled with casualties. Incarceration doesn’t only affect the person incarcerated, but entire families, and when families are hurting, it hurts communities and ultimately hurts this country. The collateral consequences of incarceration are a ripple effect that harms already vulnerable communities. The impact far exceeds just the time lost. There’s probation and the fear of violation, voter suppression, lack of opportunities in employment, and housing. The system’s purpose is much more sinister than meets the eye.

Q. How did you become involved with Last Prisoner Project and how important is it that formerly incarcerated people lend their voices to the cause?

A. While I was incarcerated, state after state was legalizing, but there was no retroactive release for those serving time for the very plant that was becoming a booming legal industry. There was no organization fighting for cannabis prisoners, so I ended up serving my sentence and upon my release I went to LPP’s second fundraiser and met the founders and began working with them to amplify the need to bring people home and to right the wrongs surrounding cannabis criminalization.

I was very unsure of how I would move forward with my life as a felon, but I knew I couldn’t sit idly by knowing the harm being done to people incarcerated for the same plant that was now being celebrated. I didn’t have much, but I had my voice, my experiences and my passion to be on the right side of this issue. Everyone has a different story, different experiences, and will touch different people. As an advocate, I look to tap into whose words will move those that can make a change. Whether those words come from the child, spouse or parent of an incarcerated person, it’s imperative that those feelings are shared if we want to see change.

Q. The goal is full freedom. How realistic is that and why hasn’t it happened as of yet? Why hasn’t legalization made a difference?

A. Full freedom is long overdue. LPP has two campaigns, The Pen to Right History and Pardons to Progress. These campaigns are an opportunity for people to make their voices heard on both the state and federal level, asking not only President Biden to fulfill his campaign promises and use his powers to sign an executive order releasing the thousands incarcerated federally, but also asking governors across this country to do the same. While cannabis is a billion dollar industry for some, others should not be serving 10, 20, 60 years for the same plant. A life sentence for cannabis is simply unacceptable. Why hasn’t retroactive relief been granted? The system is not broken but working perfectly as designed. Prisons are a business. The tens of thousands of incarcerated cannabis prisoners contribute to keeping these prisons in business. Many of these prisons are in rural, low-income areas. There is no motivation to not incarcerate people. Legalization has not made a difference because it’s making money for those intended while also further hurting those intended. Justice was never the intention of legalization. What isn’t being recognized by those in power is the collateral damage being done cannot be contained. When one community is suffering, that suffering manifests itself in ways detrimental to this country as a whole.

Q. What do you hope to accomplish with the Release Papers campaign and reaching weed smokers?

A. The intention of the Vibes Release Papers campaign is to remind people as they are rolling up and partaking in the privilege of consuming, that they are able to do so because of people who are serving time for the plant. It’s also a call to action to make their voices heard that as Americans, we don’t support the incarceration of people for cannabis.

Q. What has been the Last Prisoner Project’s most successful program to date?

A. Last Prisoner Project is a young organization that has achieved many successes. One thing that I’m especially proud of is the work of our legal team, who have facilitated early releases for people like Ferrell Scott, Jeremy Grove and Richard Delisi. Additionally, our policy team has helped pass Assembly Bill 1706, which supports record-clearing for Californians. In addition to these accomplishments, LPP has been able to give over $2.4 million in direct funding to constituents and their families through our grant programs. These grants are made possible by donations from people who care about individuals, not just laws.

Over the coming weeks, “Inside Out” will highlight the experiences of formerly incarcerated individuals and their families, look at efforts to improve local jail and prison facilities, and share the perspectives of Black correctional staffers and attorneys who work on change from within and activists who have dedicated their lives to shining a light on the inequities of the criminal justice system.