How Comic Books Became Classics

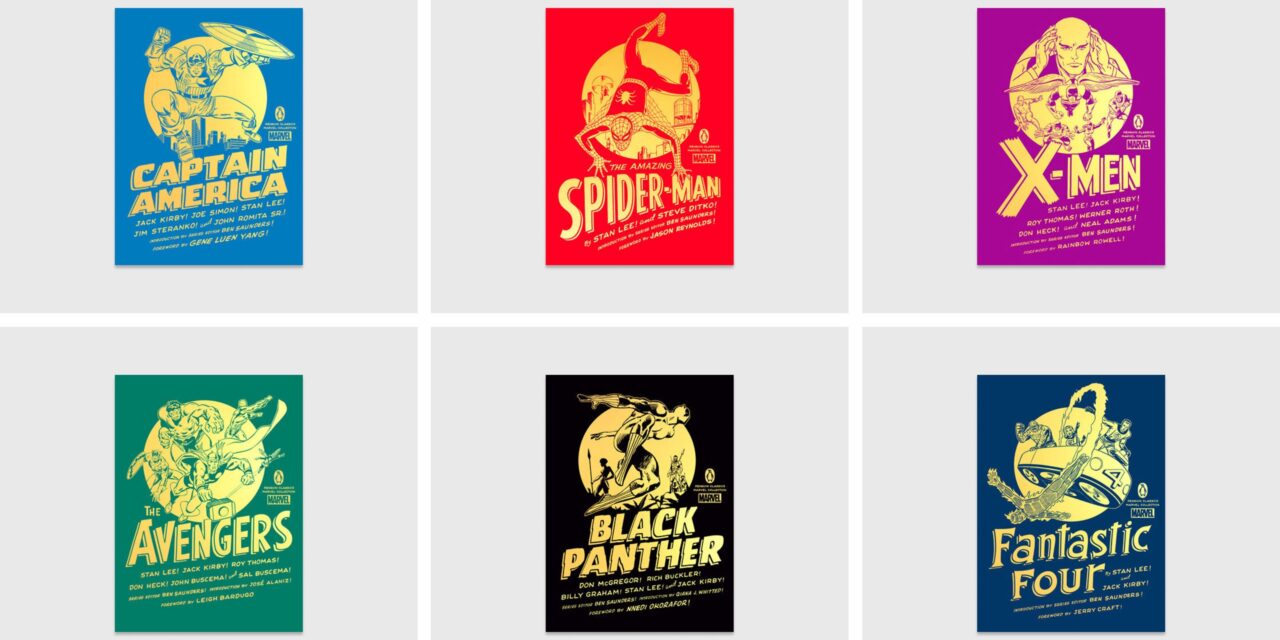

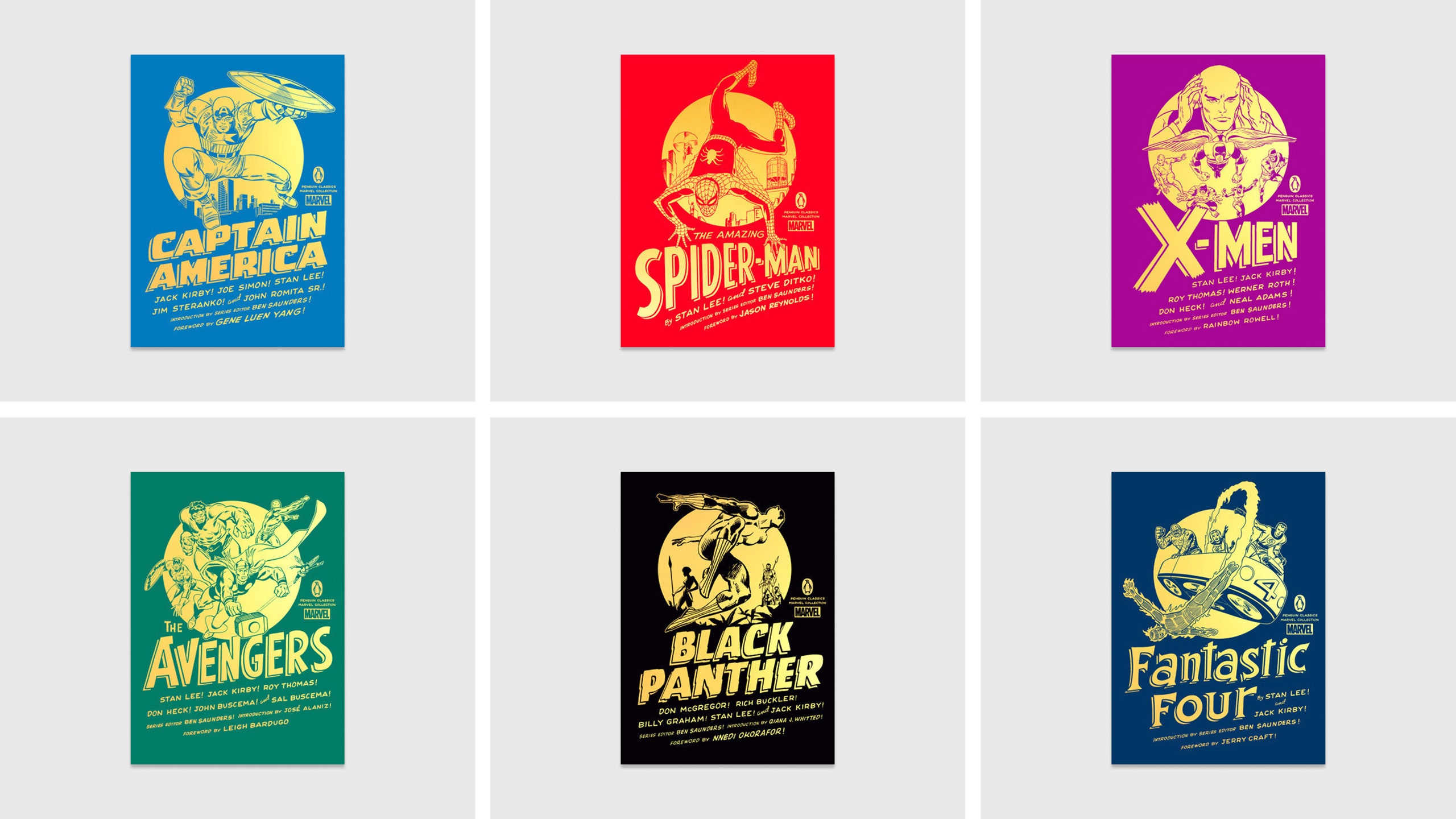

In September, 2023, Penguin Classics, the venerable publisher of elegant Anglophile editions and portable canonical texts—Robert Fagles’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid, Thomas Hardy’s “The Mayor of Casterbridge”—released three books that push the term “classic” into new, contested territory: “X-Men,” “The Avengers,” and “Fantastic Four.” These handsome hardcovers, whose gilded edges make them look like collector’s editions of Shakespeare, mostly feature early Marvel stories from the nineteen-sixties—what aficionados sometimes call the Silver Age of comics. They join Penguin volumes of “Black Panther,” “Captain America,” and “The Amazing Spider-Man,” published last year. People who think of classics as time-tested pinnacles, books we read in school, or writings by long-dead white men, may be surprised. “A classic can only occur when a civilization is mature,” one dead white man, T. S. Eliot, intoned in 1944. “It must be the work of a mature mind.” Penguin’s first Classic, published in 1946, was E. V. Rieu’s influential prose translation of the Odyssey. How did Iron Man and Wolverine come to occupy the same shelf as Odysseus and Elizabeth Bennet?

The first “classic comics,” from the nineteen-forties, were canonical novels like “Moby-Dick” and “Ivanhoe” recast in comic-book form—prestigious intellectual property that was old enough to have entered the public domain. Superhero comics from that period, later nicknamed the Golden Age, did not advertise themselves as classic, or literary, or durable: they promised excitement, suspense, and adventure, right now. So did the first stories that bore the name Marvel Comics. The cover for Amazing Spider-Man No. 1 (March, 1963) promised “2 great feature-length Spider-Man thrillers!” Its splash page made the series sound like the opposite of a classic: “there’s never been a hero like—SPIDER-MAN!”

Soon, though, the writer Stan Lee and the artists Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko began to riff on the language of prestigious literature. Avengers No. 1 (September, 1963) bills its matchup with Loki as “the first of a star-studded series of book-length super-epics featuring some of Earth’s greatest super-heroes!” You’d almost think they were writing about Odysseus or Beowulf. (They were, in fact, writing about Thor, the sometimes thickheaded storm god of Norse legend, a major Marvel character to this day.) “Epic,” once a specific lit-crit term, became comic-book-ese for any superhero story spanning multiple issues.

Silver Age epics might also echo the content, if not the details, of works like the Iliad. Their illustrated quests pit a whole culture’s values against worthy, well-meaning opponents: just as Homer’s prince Hector strives to protect Troy from marauding bands of Greeks, the Marvel antagonist Prince Namor, the Sub-Mariner, wants to defend his Atlantean realm from human incursions. The Iliad, too, introduces teams of heroes who go on to further adventures; its spinoffs include Virgil’s Aeneid and Chaucer’s “Troilus and Criseyde.” Marvel’s Avengers is itself a spinoff, a way to bring together Iron Man, Thor, the Hulk, and others. It establishes their shared quasi-mythological world—and that allowed Marvel to market new heroes to readers who loved the existing ones.

Marvel followers became fans, not only of Spidey and Thor, but of Marvel itself. They saw creators within the comics, in bits of metanarrative that predated, by decades, the easter eggs and Stan Lee cameos in Marvel films. “In this epic issue surprise follows surprise,” the cover of Fantastic Four No. 10 promises, “as you actually meet Lee and Kirby in the story!!!” Adult and teen fans wrote fulsome letters to editors, which were printed in the comics they loved. “We are both 22 and my husband is a college grad,” one correspondent in Avengers No. 26 boasts. They could join the Merry Marvel Marching Society, an authorized fan club, claiming titles such as “T.T.B. (Titanic True Believer)” and “K.O.F. (Keeper of the Flame).” And they competed—again, through the letters pages—for Marvel’s No-Prize, an otherwise worthless certificate awarded to fans who explained away an inconsistency, an artist’s mistake, or an editorial goof. Comics were on their way to becoming classics in a different sense: not ancient, not necessarily educational, but adventure stories that formed the basis for further adventures, around which strong communities could materialize.

In his influential book “Imagined Communities,” Benedict Anderson argues that shared reading—newspapers, pamphlets, novels—made modern European nations possible. Frenchmen were people who shared news and stories in French; English people came together through the Illustrated London News, the books of Dickens, the cult of Shakespeare. By the time Jack Kirby left Marvel, in 1970, and Lee stepped down as editor-in-chief, in 1972, they and their colleagues had founded a kind of miniature nation: followers versed in a language of secret identities, geographies, and histories, eager for news that only they understood, and ready to forge a next generation. Roy Thomas, who took over X-Men and then Avengers in 1966, became the first of many Marvel fans turned pros, who grew up reading superhero comics and then got hired to make them.

Scholars tend to argue that Silver Age comics had staying power not because they were timeless but because they were of their time. Whereas Golden Age paragons like Superman and Batman were larger-than-life role models, Silver Age heroes had regular-people problems. Spider-Man, as Peter Parker, always needed money and rarely got the girl. “Why don’t things ever seem to turn out right for me?” he reflects as he shrugs off his costume. “Why do I seem to hurt people?” The X-Men’s initial teen-age roster included a class clown (Iceman), a smarty-pants (the acrobatic Beast), and a grimly responsible team captain (Cyclops), afraid to ask out the girl of his dreams. The Fantastic Four live, work, and squabble like a lovable and recognizable family. Readers—especially, but not only, young men—could see their own troubles in these figures. These comics reflect the sixties (with the exception of Black Panther, who got his first multi-issue arc in the seventies). They’re preoccupied with underground nuclear tests, groovy youth in revolt, and pop-Freudian psychoanalysis. “It might take you months to psycho-analyze me! I can’t spare the time!” a beleaguered Steve Rogers (Captain America’s alter ego) complains.

Timeliness alone, though, wasn’t enough to keep all these comics alive, let alone usher them into a canon. X-Men sold so few copies that Marvel stopped publishing new adventures in 1970. (The series became popular, even iconic, only in the late seventies and early eighties, with a new creative team—led by the writer Chris Claremont, the artists Dave Cockrum and John Byrne, and the writers and editors Louise Simonson and Ann Nocenti.) Captain America wasn’t even from the Silver Age; Kirby and Joe Simon created him in the forties, and his adventures in the sixties emphasized his status as a holdover from the Greatest Generation, a lonely man out of time. The strongest comics collected in these books not only captured their era but pointed beyond it.

Stories become classics when generations of readers sort through them, talk about them, imitate them, and recommend them. In this case, baby boomers read them when they débuted, Gen X-ers grew up with their sequels, and millennials encountered them through Marvel movies. Each generation of fans—initially fanboys, increasingly fangirls, and these days nonbinary fans, too—found new ways not just to read the comics but to use them. That’s how canons form. Amateurs and professionals, over decades, come to something like consensus about which books matter and why—or else they love to argue about it, and we get to follow the arguments. Canons rise and fall, gain works and lose others, when one generation of people with the power to publish, teach, and edit diverges from the one before.

For the generation now in charge of literary publishing, comics can be classics. We can see, in retrospect, why these titles, and these specific issues (Fantastic Four Nos. 48-50, say, but not No. 43), count. “Classic” issues of Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, and the rest represent high points in serial comics as visual art or turning points in the stories—and often both. The stories that mattered to fans could have lower, less obvious stakes than the ones that covers touted. We know that the shape-shifting Skrulls won’t destroy the Earth, because otherwise there would be no next issue. But will Cyclops ask Marvel Girl out? Will Reed Richards marry his girlfriend, Sue Storm? That we don’t know until we read. It’s the logic not so much of adventure tales as of romance comics, which Marvel also published. (See Millie the Model.) Douglas Wolk, who read every Marvel comic published between 1961 and 2017 for his book “All of the Marvels” (2021), has explained that Marvel’s signature sixties titles proliferated by “absorbing monster comics and romance comics and humor comics into superhero comics.” Adventure, but also angst; slugfests, but also sarcasm and soap operas.

Black Panther’s journey into this canon started later and took a different path. Penguin’s edition opens in 1966 with the first appearance of Wakanda, a techno-utopia “in the heart of Equatorial Africa,” in a Fantastic Four comic. Then it skips ahead to sixteen comics published between 1973 and 1976. All were scripted by Don McGregor, who developed the mythology—Killmonger, Warrior Falls, the Palace Royal—that later scripters and screenwriters would use. (“When I was taken off the Panther,” McGregor has said, “I was told it was because I was too close to the black experience. I looked at my white hands.”) McGregor and the penciller Billy Graham fashioned a warrior-king who could be a superhero outside Wakanda, but had to learn to be a decisive ruler and a romantic leading man at home. Wakanda existed at a distance from the rest of the Marvel Universe—conceptually and literally another country. It had to wait decades, and get a boost from Hollywood, before it could become more than a cult sort of classic.

When prose writers rose to literary prominence, in the eighteenth century, lovers of verse deemed the medium vulgar. It can take years for such attitudes to change, and comics are a particular departure: they are not only a textual medium but a visual one. A top-flight comic by Kirby—or his successor on “Captain America,” Jim Steranko—barely needed words. You could follow the story just by watching the characters act and react. Thankfully, Penguin volumes do justice to these images. They reproduce sixties comics in bright, flat, colorful inks on thick white paper—unlike the dot-based process used on old newsprint, but perhaps truer to their bold, thrill-chasing spirit.

In Fantastic Four Annual No. 6 (1968), one full page shows an orange-and-black Thing falling backward, through magenta nova-bursts. The Torch narrates as he is “helplessly flung thru space . . . like a team of powerless rag dolls!” In the foreground, Reed Richards screams in pain; we see just his face, with the rest of him out of frame. He falls monumentally, like Icarus in a Baroque painting. Throughout Kirby’s stories—especially in Fantastic Four—space-age heroes sweep across fantastic backdrops: stars, nebulas, even black-and-white photo collages, with hand-drawn figures superimposed. The apex of Kirby-craft, assisted by the inker Joe Sinnott and an uncredited colorist (likely Marie Severin), appears slightly earlier, in the spectacle of Galactus—a gigantic, often purple-helmeted, purple-prose-spouting bad guy. He is a spacefarer and a spectacle, cosmically indifferent to human suffering. No subsequent comics artist has equalled him yet.

Lee, Kirby, and Ditko are now dead white men. Classics, by definition, have aged, and some parts of these books aged badly. Despite the Thing’s example, conventionally ugly or visibly disfigured characters are usually villains, from the scarred and vengeful Madame Hydra to the big, round, glum Blob. Attempts to address the civil-rights struggle suffer from a milquetoast centrism. Villains explain their plans for no good reason; everything comes with exclamation points. Women (or “girls,” like the Invisible Girl) have feminine powers, like shrinking, or espionage, or invisibility; rarely do two or more women converse. Some plots make little sense. But these comics share such flaws with almost every other product of popular culture from that era, and many from our own; we keep reading them for what makes them stand out.

Silver Age Marvel meant feelings (Cyclops and Marvel Girl’s lovesickness in the X-Men; the Thing’s depression in the Fantastic Four) and spectacle: a world to astonish the eyes, with new perspectives, shiny interstellar gadgets, and heroes always in motion. But that world, in comics, was able to do more, for more readers, in the absence of competition. Before modern digital graphics, before “Star Wars,” before video games, only in the pages of four-color comics could such cosmic deeds and superhuman feats find appropriate visual form. The special effects from sixties movies look kitschy today, but the visuals from early-sixties comics translate surprisingly well to modern screens.

For modern superhero comics, that’s a problem. Longtime Marvel characters now fit into epic movies, from “X-Men” to “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse.” Like other classic stories that are being reinvented today, they work on TV, at least sometimes (“She-Hulk,” “Ms. Marvel”), and they inspire literary fiction, from Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer-winning “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay” (2000) to Bob Proehl’s overlooked and heartbreaking novels about superpowered mutants, “The Nobody People” and “The Somebody People” (2019-20). In short, today’s superhero comics have competition. Although the broader medium is doing fine—see Alison Bechdel’s slice-of-life graphic memoirs or Raina Telgemeier’s comics about kids—staple-bound serials now have an identity crisis. Drugstores no longer sell them; only specialized comics shops do. (You can also pay to read them online.) The best-selling comic book of all time, an issue of X-Men from 1991, hit sales figures that will probably never be equalled. Video games may better fulfill our fantasies; Netflix is easier to navigate.

What superhero comics still have are ongoing stories about ever-evolving characters and the worlds they share. They’re a locus of community for fans who want more stories, or different stories, than Hollywood can offer, and they have room for new artists, new writers, and new heroes on old teams. Because they’re so much cheaper to make than film or TV, they sometimes let writers take more risks. You won’t find friendships between young, explicitly trans people taking center stage in a Marvel movie, or in Silver Age comics, but you can see exactly that in beautiful, intricate issues of Marvel’s New Mutants (2020-23), written by Vita Ayala and then by Charlie Jane Anders.

Eliot opined that true national classics had to display a “whole range of feeling” and to elicit “response among all classes and conditions of men.” The Marvel Universe, all in all, arguably comes close; Wolk calls it a “mountain, smack in the middle of contemporary culture,” that “never stopped growing.” But readers who walk away, or give up, or pass on, will have to be replaced by new generations. Super-movies may keep coming, and archival editions may keep rolling out, as long as they make money. Without new people in the comic-book stores, though, and without stories that hold a new audience, Marvel comic books risk becoming what Mark Twain said a classic was: “something that everybody wants to have read, but nobody wants to read.” Not even Galactus wants that. ♦